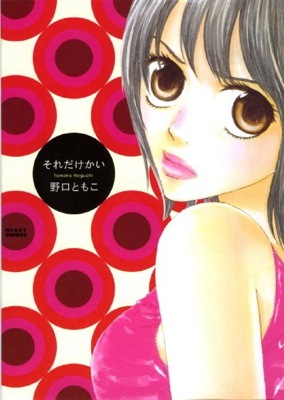

There’s been a bit of a blog tour about Josei, or manga for grown women of late. A podcast with Johanna Draper Carlson, David Welsh and Melinda Beasi can he heard here and includes lots of links.

Johanna has a really excellent piece called A Timeline of Josei Manga in the U.S. tracking such things as Erica Sakurazawa, Luv Luv, and Suppli.

Beasi has more extensive thoughts on how the genre of comics for adult women can have an uphill climb:

Readers do it, and it’s hard to blame them either. Who hasn’t been put in the position of having to over-explain to a skeptical friend, “I know the cover is pink, but it’s really good, I swear!” We explain because we think we have to, and we think we have to because we’ve been conditioned to believe that something specifically created with girls or women in mind is less well-crafted, less intelligent, and less universally relevant than something that’s not. I came down pretty hard on female readers in that earlier HU article for distancing themselves from “girly” stuff, but there are a lot of reasons why that happens, a lot of traps set for women to fall into, and it’s really quite difficult to avoid those traps since they’ve been in place for so long.

The josei category includes a lot of great books — Viz and Yen are still putting some out, but hopefully it won’t disappear entirely in the US.

Something people do need to consider, however, is not to expect too much from Josei manga. It’s not a function of gender issues or anything like that but rather a function of the fact they’re essentially written for the same market as the women who buy the books with Pictures of Shoes on the front.

The same is true of Senin stuff. I love me some Naoki Urasawa but the guy essentially writes airport books in comic form and pretending their otherwise is a bit of stretch.

(Though you can make a whole case about how American ‘mainstream’ comics don’t actually do this)

Manga is the most populist and mercenary of comics mediums and expecting more than that is perhaps a little bit of a stretch.