Maybe it’s the times, but the comic book industry is undergoing a boom in horror series right now, with titles like Gideon Falls, Die, and Infidel winning wide-spread critical acclaim.

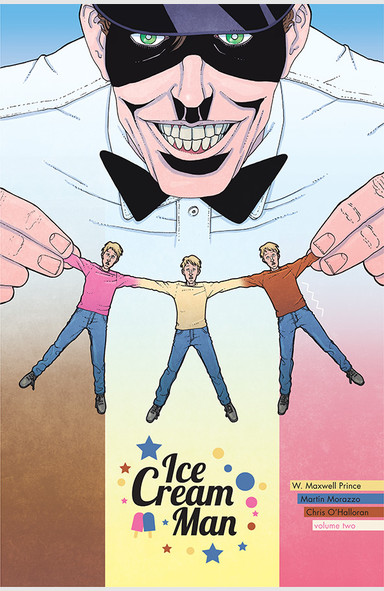

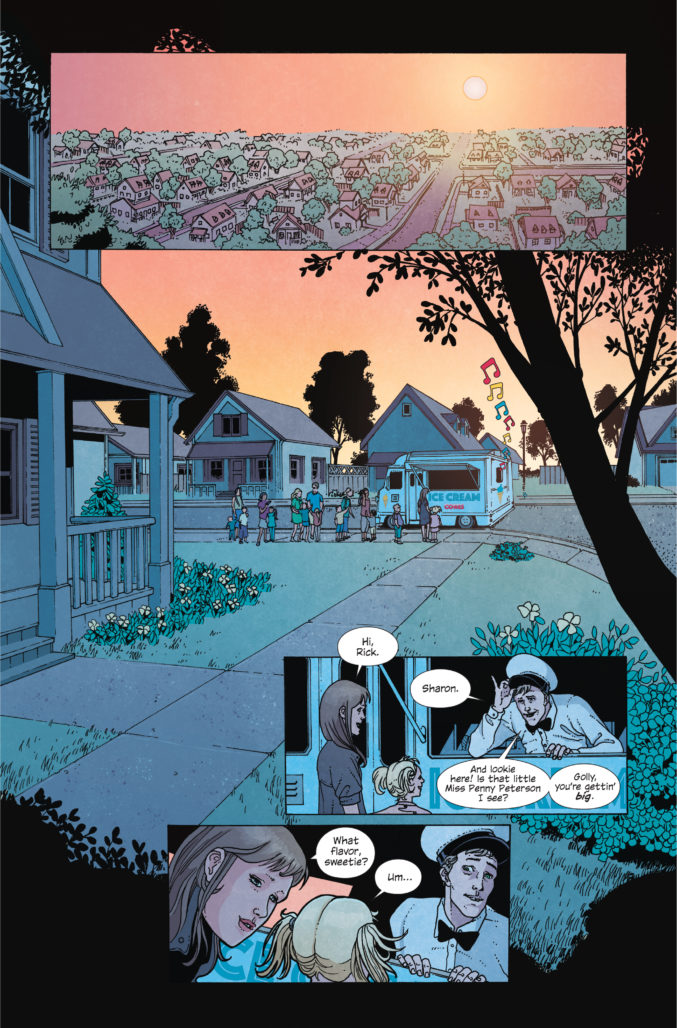

A unique and standout entry within this recent horror boom is the anthology series Ice Cream Man by writer W. Maxwell Prince, artist Martin Morazzo, colorist Chris O’Halloran, and letterer Good Old Neon. A wildly creative comic that often plays with form (Ice Cream Man #13, which just came out this week, is written and designed as a palindrome that can be read backwards or forwards), the book weaves together a series of short pieces that deal in everything from addiction to murder to existential dream. The lone unifying presence is a white-clad ice cream man with glowing green eyes and sharp teeth.

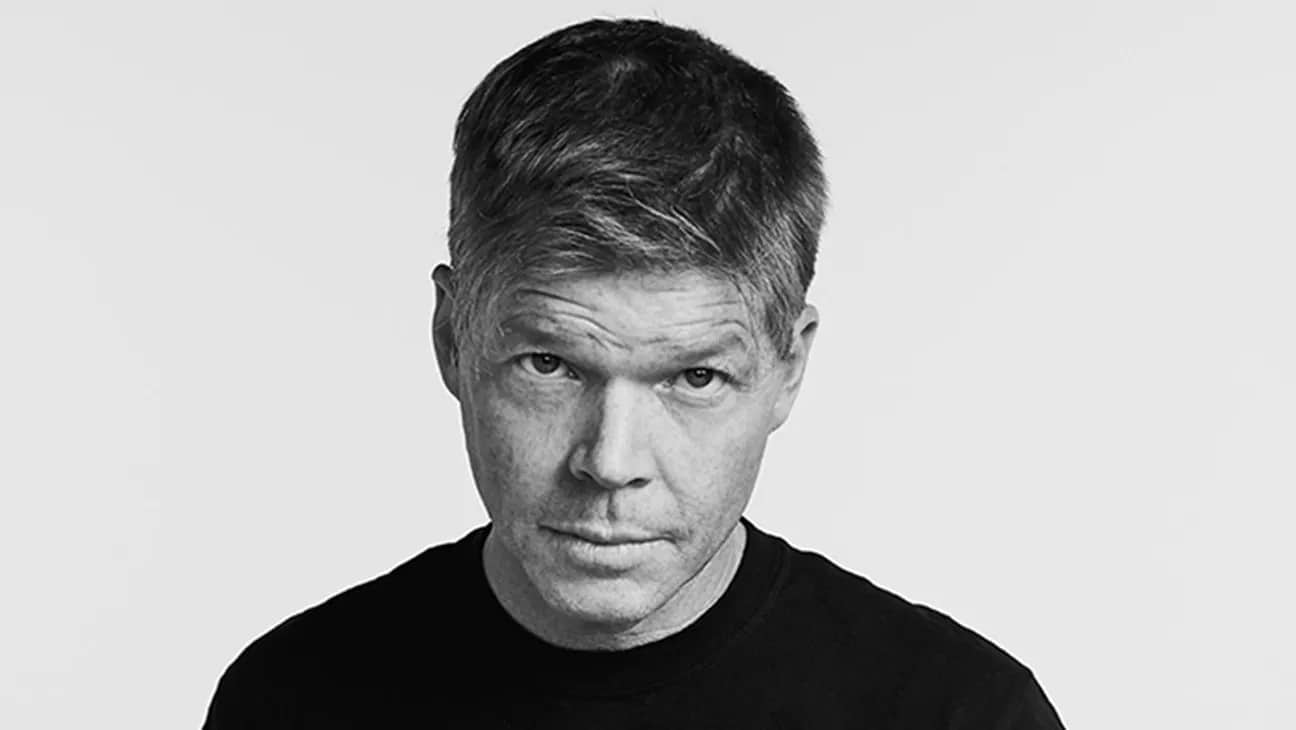

It’s deeply unnerving stuff, but it also at times has a humanistic sensibility that seems to be battling to break through. It’s all very compelling, and so we jumped at a chance to talk with W. Maxwell Prince at this year’s San Diego Comic-Con.

Check out the interview below…

The Beat: Can you talk a little bit about the genesis of Ice Cream Man? How did you land on these type of stories and this format?

W. Maxwell Prince: The book I did before Ice Cream Man at Image was this graphic novella called One Week in the Library. It’s this highly experimental thing where this librarian is stuck in—we’ll call it a magical library—and each chapter is a day of the week. Each chapter plays with a different type of storytelling. One chapter is told through infographics, another chapter is silent, another chapter is all prose. I came to that project after doing some things at IDW that were more serial in nature, and I found that my strengths as a writer were compressing my ideas down into a shorter space, not trying to say something in four or five or six issues, but to get in and get out.

I just started to write all these short stories for comics in my notebooks, but I didn’t have much of a justification for why I should release them together. None of them really had much to do with each other. Tonally they were similar, but it was clear they couldn’t really be put together as a book. I watch a lot of the HBO show High Maintenance. I just love it. It’s a really compassionate show. It looks at people through a compassionate lens, and usually the resolution of each person’s story ends on kind of an upnote. That idea that the weed dealer is in every episode and he’s the thing that’s tying these stories together. I thought, ‘Oh, what if you could do that for comics?’

I don’t really know how it came to an ice cream man, but it was the structure of High Maintenance with these short stories I’d already been working on. Eventually, it became this creepy dude.

The Beat: The recurring characters—the ice cream man and Caleb the cowboy—there have been some issues that feature them more of late. Do you have a full arc with an ending in mind?

Prince: The original idea was to not really ever get into that, to just have the ice cream man be this presence, but after I’d put out a couple of issues, people were asking, what’s the ice cream man’s deal? They wanted to know more about the ice cream man, and it made me realize that maybe it would be beneficial to not focus on that—because I still wanted to tell short stories about people—but maybe there was a way to weave through a mythology to get to the issues. I started to play with the possibilities of what the ice cream man could be.

I do have a plan to go back to the world they’re from and reveal a little more, but I would never want to define it so explicitly. These people are kind of the embodiments of ideas and feelings and inclinations in us: the ice cream man being the part of you that tells you that things are pretty shitty, and then Caleb being the part that says, no, chill out, it’s not all bad, there’s actually good stuff too.

Issues 13 through 16 don’t touch on that world really. It’s a stand alone arc where I’m playing with things through format. These next four issues are format plays, and then issues 17 through 20 go back into Caleb, the ice cream man, that kind of world.

The Beat: My favorite issues is probably Ice Cream Man #6, the neapolitan issue. I think that issue is an achievement, to be able to tell three distinct stories with little to no dialogue that have almost nothing to do with each other but also everything to do with each other was incredible. I wanted to ask what was the creative process like for coming up with that?

Prince: I found the best way for me to finish writing an issue is to present a hard problem for me to solve, to almost make it like a puzzle. There are some issues where I don’t have to do that and the story presents itself naturally. Other times, a good way to propel myself forward into writing and working with stories is to come up with a structure and a challenge that will get me excited.

Going back to One Week in the Library, there was a silent issue in that, and that chapter got nominated for an Eisner. I wanted to revisit that format, and I had a whole story setup where it was just one story being told silently. For some reason, in my head there was a panel where he got three scopes and they were neapolitan. I thought, what if that could be a motif of this whole issue?

I just worked through it. I could tell three silent stories where these different exceptional things are happening, but they are all in a way the same story. Another part of this is I feel almost guilty writing a whole silent issue, so I want to make sure there’s a lot of meat for someone. Once I had the idea, I worked through my notebook, trying to figure out where the stories split, how I could pace them to somewhat match each other, and then also pace them to land on certain pages at a similar note.

A lot of it was taking pages four through seven and getting them on the same track. I really told the story in increments to make sure none of the narratives deviated too far in pace, scope, and tone. It was trying to figure out what I would show to make them all run at the same speed.

The Beat: I don’t want to call it catharsis, but it definitely seems like you’re working through some things with this book sometimes. How aware are you of that while you’re writing?

Prince: I had a daughter two-and-a-half years ago. It’s cliche, but your perspective and priorities change. With the kind of world we’re living in right now, it’s really anxiety inducing to have a human life you’re responsible for. I found that all these ideas about the way people are, the way the world works, how certain things are unfair, how certain things don’t make sense, how certain things are beautiful—I’ve always been a person who thinks of that stuff anyway, but once I had a daughter, it all started to bubble up.

It was pretty raw. I was worried about doing right by this person. I’d have something I was worried about over the course of a week, and I would find it would make its way into my book. Issue four is about a person who is not sure if they want to be a dad, but he’s also negotiating his friend who just died, and that friend’s dad wasn’t there for him. He then has to see this man have this regret at the end of his life for not being there for his child. That was all culled from stuff I was going through, being really nervous about being a new father, and then seeing friends of mine having relationships with their fathers that were strained or non-existent.

That’s one example, but there’s actually a lot of child anxiety in these issues. There’s a baby in the neapolitan issue and issue seven is about what if your kid gets lost. All this stuff makes it way into the book.

The Beat: In the first arc, there was a lot about small towns and normalcy. Were you trying to say something about the suburbs?

Prince: I don’t know if that was intentional, but I grew up in the suburbs, in New Jersey. They were down the middle, middle class suburbs. When you’re a kid, you start to realize your quaint little town is a lot more messed up than you think. My most shocking memory as a child: my mom was driving us somewhere and there were a lot of dirt roads in my hometown. My mom was in a fun mood, and she was like, ‘why don’t we go down it?’

So, we go down it and what we discover at the end of it is a shooting range, and it was a shooting range run by a local chapter of the KKK. That was the juncture my mom has to explain to me who the KKK is and what hate for other people is. It’s similar to the Goonies finding an underground world: your little town has stuff that is just beyond your comprehension.

The suburban focus is that. Beyond the ice cream man being a horrific presence, there are horrific things going on in these towns that have nothing to do with him.

The Beat: Has this book changed your relationship to ice cream at all?

Prince: My relationship to ice cream has changed just in growing up. When you’re a kid, it’s a treat, it’s a dessert. Now, what happens is I get ice cream at the end of a long day, I treat myself, I indulge, and I feel like crap, I feel fat, I want to go work out. It’s this thing that’s sort of encapsulated in Ice Cream Man itself. This thing you love as a kid is a different proposition as an adult.

The ice cream man, here’s this guy offering a little salvation in the form of ice cream. Then as an adult, you realize it’s weird these adults just drive around in these vans. We teach our kids don’t ever take candy from a stranger in a van…except if he’s selling it.

Comments are closed.