And yet, Bakshi is not the only well of inspiration that King and Gelatt took from when putting together The Spine of Night. If anything, what they did was turn their story into gathering place for ideas meant to push the very concept of fantasy into places that beg further exploration and further recognition.

Directed by King and written by Gelatt, The Spine of Night is a dark fantasy tale about powerful magic falling in the wrong hands and how a moment of evil can lead to a struggle that spans entire eras and generations. It features an impressive cast of voice talent that includes Lucy Lawless, Joe Manganiello, Patton Oswalt, Richard E. Grant, and the scene-stealing Betty Gabriel.

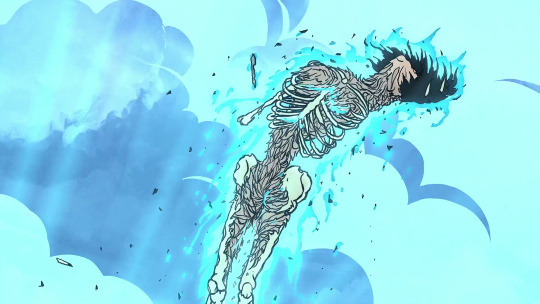

The story is divided into stories told by a witch called Tzod (Lawless), the wielder of a type of magic that stems from a plant that holds infinite power. This plant is stolen from her after her people are massacred and used to create a violent empire that plunges the world into a new age of war and conquest. Tzod tells her stories to The Guardian (played by Grant), a being that protects one of the last available sources of the powerful plant.

The movie is a gritty, hallucinogenic, and brutally violent affair that considers not just the corrupt nature of power but also the environmental consequences of such a pursuit. I was struck by how well the latter was implemented. It’s a theme that makes the multilayered story feel current, consciously keeping the idea from not getting lost amongst the many influences and classic fantasy references King and Gelatt cram into it.

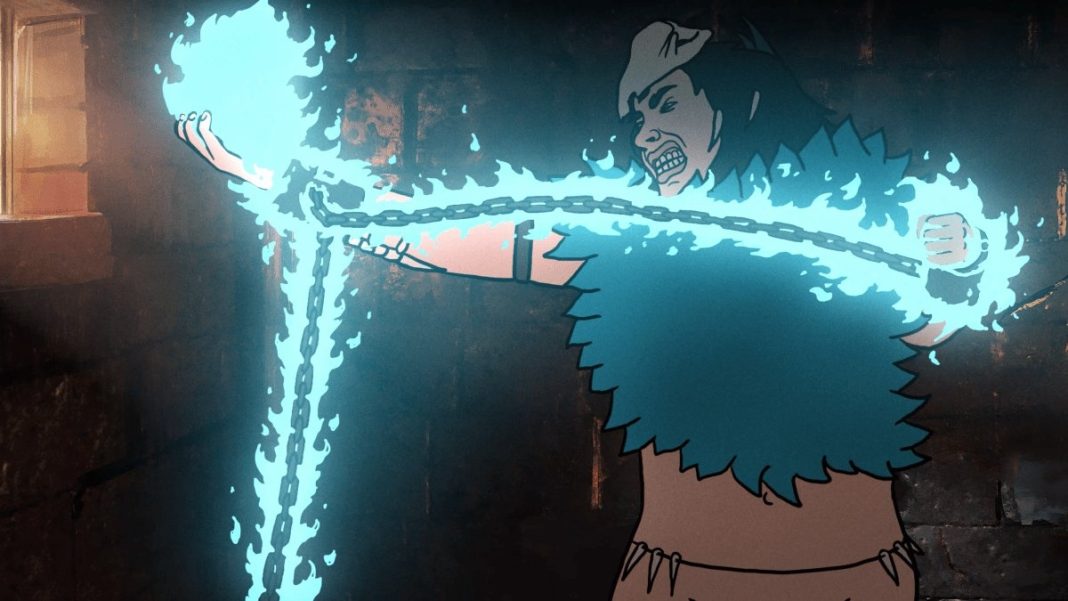

To watch but a trailer of the movie is enough to appreciate the care that went into the rotoscope animation, which involves shooting the story with real-life actors first and then drawing over them (in addition to all the wondrous things that populate the narrative). The overall design of the visuals is where we can find King and Gelatt’s unique blend of inspirations and variations on formula, distinct enough to forge an identity it can legitimately call its own.

The Beat corresponded with King and Gelatt to discuss all manner of things that went into the creation of The Spine of Night and how it all came together for a dark fantasy movie I hope we get to see more of in future instalments. It follows below.

RICARDO SERRANO: Today’s animation landscape is overwhelmingly digital, with Pixar and Disney Studios largely sticking to that format for their movies. While you’re clearly not aiming for kids with The Spine of Night (not by a longshot), what made you go with rotoscope for The Spine of Night? Do you think younger audiences can embrace that style of animation further down the road?

MORGAN GALEN KING: Rotoscoping always felt like the right choice for the film. We both grew up in the era when rotoscoping was last having a spike in popularity alongside the Fantasy boom in the late 70s and early 1980s, and wished there was more of that style of things still being made in the world. And I think the hand-drawn aesthetics of the era are a natural fit for the style of psychedelic, existential sword & sorcery themes we wanted to explore.

As for younger audiences, I suspect that the software tools for young people to start making automated rotoscope-ish animation on their phone are only half a decade away, so I would not be at all surprised to see the style have another boom in popularity in the near future. It’s been a part of animation since the very beginning of motion pictures, and its popularity has come in waves every couple of decades when the cultural pendulum moves towards wanting to see more realistic human bodies in animation.

PHIL GELATT: Yeah, I think it basically HAD to be rotoscoped. That’s as big a part of what makes it what it is as the fantasy genre itself. To imagine the film in a different style is to imagine a totally different film. People often talk about the film in terms of nostalgia, and I understand that, but for me the film is much more about confronting a thing you loved in the past and dragging it into the present. That for me is part of the appeal both in the animation style and in terms of that low fantasy sword & sorcery genre.

As to the kids getting into it? I hope so!

SERRANO: The Bakshi influences are front and center in Spine of Night, but there are other strands of fantasy and horror that are at play as well (I was often reminded of the Castlevania video games and the 1989 movie Warlock). What other works influenced the making of your movie?

KING: Oh, yeah – I am sure Castlevania: Symphony of the Night and a whole range of Fantasy-Horror games have had an influence – I certainly share a love for bearded helms with Dark Souls! Horror movies have always been a big part of my life, and there’s a lot of Evil Dead influence in the gore, and there’s small nods to Hellraiser and Creepshow 2 in there, and I’m sure plenty of subconscious influences I’m not even aware of. I was rewatching the 1981 Clash of the Titans not too long ago and realized that the ancient mausoleum surrounded by obelisks from that – Medusa’s lair – was surely a forgotten influence on the necropolis at the beginning of The Spine of Night.

As far as animation influences go, certainly Heavy Metal (the movie and the magazine) had a huge impact on me as a kid, and I was in love with MTV’s adult animation anthology show Liquid Television – Æon Flux and The Maxx, and things like that. And before that, Thundarr and The Black Cauldron imbued an early love of dark-tinged Fantasy animation, alongside Bakshi’s work and the Rankin-Bass The Hobbit. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention how important Walter M. Miller Jr.’s sci-fi novel A Canticle for Leibowitz was on the structure and themes of the film, too – that’s an absolute classic.

GELATT: Yeah I adore the fantasy genre in all its many flavors and sub-genres. For me this movie was a chance to bring to screen a sub-genre that’s not often seen in film. Call it low-fantasy, ‘70s era, psychedelic fantasy. Akin to things like Elric, or Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, or the works of Fritz Leiber.

My ultimate fantasy film would probably be something like the 1982 Conan film mixed with Kubrick’s 2001. Something that is gritty and grounded, but also cosmically minded. A blend of feet on the earth, head in the stars.

SERRANO: Europa Report was such a great sci-fi movie that succeeds in being so inventive with a story about a team of scientists looking for life in Jupiter. It leaves a lot up for the audience to decipher, much like Spine of Night when it comes to its world and lore. Did you bring certain lessons or ideas from Europa Report into The Spine of Night?

GELATT: I love movies that trust their audience to pay attention and to want to engage. That’s I think really the lineage there, and it applies as well to my 2018 film They Remain. My hope is that they’re all movies that ask the audience to do some work, to put their own imaginations into the film and explore the story being presented in order to come to their own conclusions.

I guess there is this feeling, generally, that a film should be telling or teaching you something. I don’t really buy that, I think film’s should ask you something interesting and then you should answer the question yourself.

That’s really the strain that connects these things. I want the movie to stay with the audience after it’s done… and I know, for me, films that leave mysteries and ambiguities for me to sort through are the ones that stay with me for years and years.

SERRANO: Now that you’ve seen an entire movie through using rotoscope, would you create another one in that style and what would you do differently?

KING: When we finished animating the film, I swore I’d never do something so labor-intensive again – this took 7 years to draw by hand! but… now that a bit of time has passed, I’m increasingly interested in seeing how much further we can push the aesthetic using more modern tools and a larger team. I think we did a pretty good job of recreating the old style that I love, especially given how small our team was in comparison to those productions, but there’s a long list of things we could do that I think would actually advance the style further in ways that it never had a chance to back then, and could do so without losing the aesthetic appeal that makes that era of Fantasy and animation so fun.

SERRANO: Can you let us in on what you’re working on next? A trip deeper into the Spine of Night universe?

KING: For me, it’s all still pretty much up in the air. I’ve been doing some more experimentation with the animation style and workflow, and Phil and I have been writing scripts and outlines for the past year, much of it related to more stories in the same setting as The Spine of Night. We’re exploring a few other things, too, but we’ll see how the wide release of the film goes, and figure out the next steps from there.

GELATT: I’m dying to do more work in the fantasy genre and to return to the universe of the Spine of Night! But in the meantime, I’m busy on a few other projects. My main focus right now is a sci-fi videogame I’ve been writing for years very much in the vein of Europa; and an animated tv show that is very much unlike anything I’ve written before.