Earlier this week, the Beat ran the first half of our interview with cartoonist Tillie Walden in celebration of the release of her new graphic memoir, SPINNING. The second half of the conversation is presented below.

Tillie Walden is a force of nature. At 21, Walden has already assembled a lengthy bibliography. She’s written and illustrated short stories such as I Love this Part as well as the graphic novel The End of Summer. Her recent webcomic, On a Sunbeam, was nominated for an Eisner during this summer’s awards. Known for her ethereal art style and ability to put out work at an outstandingly rapid pace, it’s clear that Walden is one of the hardest working cartoonists in comics today.

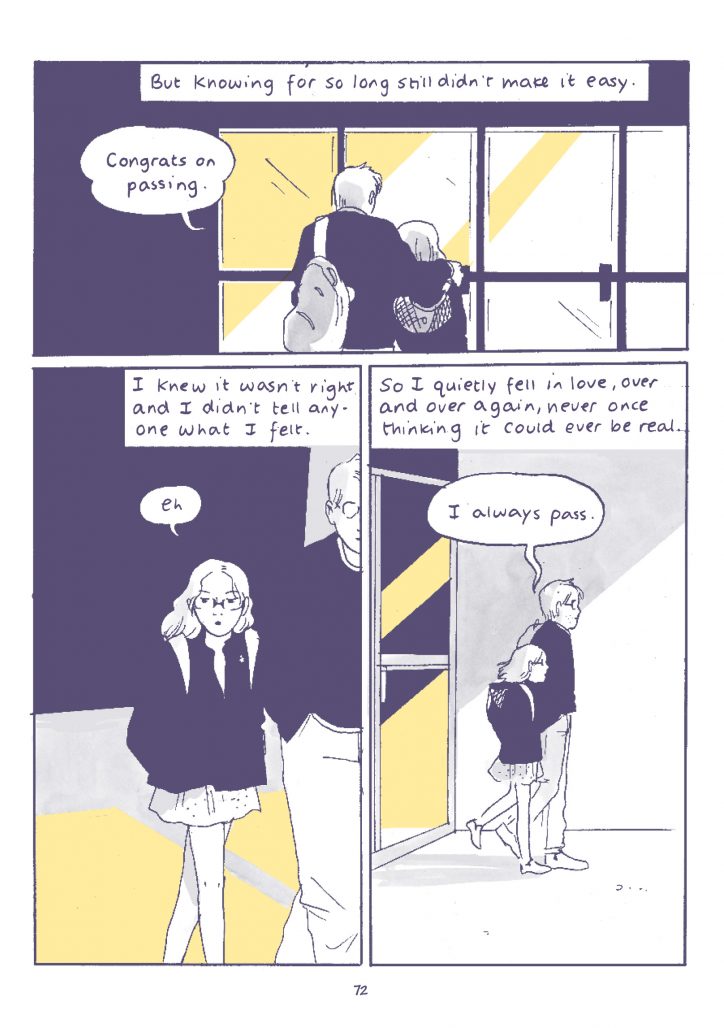

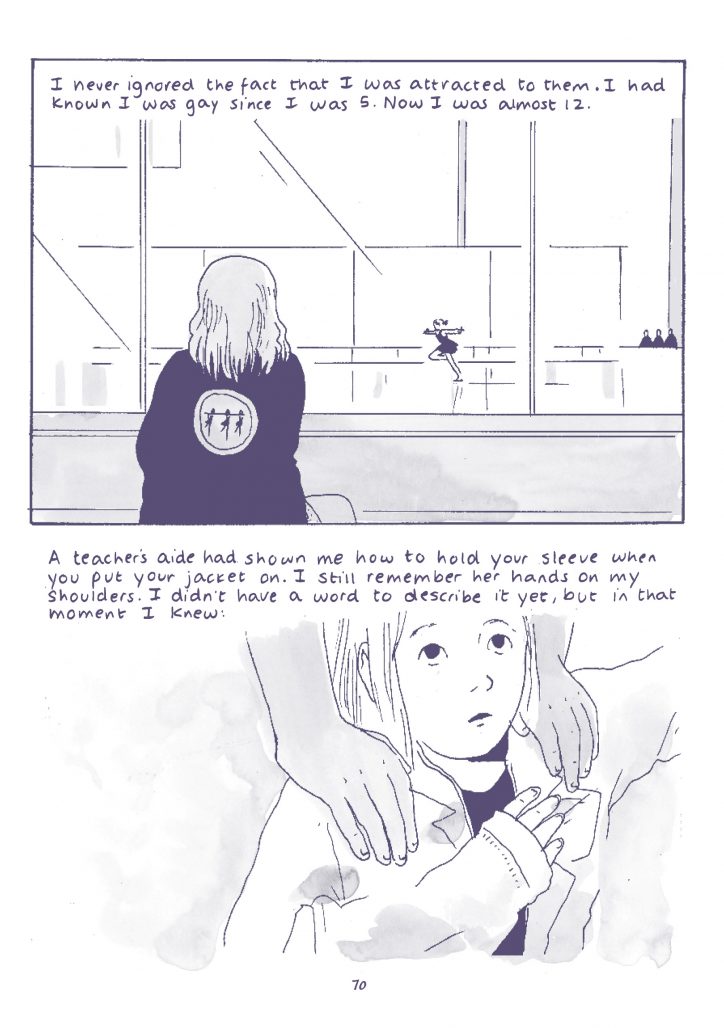

This week, publisher First Second released Walden’s first graphic memoir, Spinning. The book follows Walden throughout her childhood figure skating career. In it, Walden recounts the unique pressures she faced on the ice and off. Through various anecdotes, we learn how Walden was shaped by her childhood move from New Jersey to Texas, how competitive skating informed her approach to life, and just how complicated it all became as she developed her personal and sexual identity.

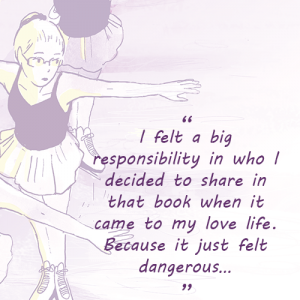

In the second part of this two part interview, Walden discusses what it means to write an autobiographical comic but still want to hold onto her privacy. She and the Beat also discuss exactly what privacy means to their digital generation and what happens when you dive a little too deep into the internet…

Walden: Yeah, I don’t think that’s it necessarily. That seems to be the case for this conversation, but there are all sorts of kinds of memories and things that I decide not to share. I wanted to make this book because I wanted people to understand what it was like to be an ice skater– especially a young, lesbian ice skater– because I think that’s fascinating and more people should hear about it. There’s also a part of me that’s very rah-rah about wanting to show the world how ice skating really feels.

But I felt like I really just needed the memories that could tell that story and that was it. I didn’t need to put in anything else that I remembered from skating. Because I can’t. Skating was my whole life. There is so much. And there’s also stuff outside of skating that isn’t in there at all.

Lu: Even with a name change, it would still be like you were outing them to some extent.

Walden: Absolutely, absolutely. I felt comfortable sharing the story about this girl in Spinning because this is the same girl that I Love This Part is about. She had already read that, so I felt like we already have this relationship where we’re both comfortable with me talking about what we experienced together. But with other girls, just because it’s Texas and I still feel the weight of homophobia, especially in the south, I just felt like I couldn’t. But, it’s funny, because now people read that book and think I only had one girlfriend. But that is not the case. My goodness.

Walden: Yes, well, Austin is kind of a weird case because Austin is pseudo-liberal. People really love to think of Austin as a liberal haven, but that is simply not the case. There are liberal people there, but for the most part, it is still in Texas and Texas seeps in from the edges of Austin. Literally, the areas around central Austin get more conservative and more Texan as you spread out from the center of the city.

The homophobia I experienced in Austin really just felt…it was just in the air. It was less the stereotype that people think though, where someone might call me a fag or a dyke– although plenty of people did call me a dyke. I actually didn’t realize that was offensive until later. I thought, “well, maybe that’s just a term for lesbian and they know I’m a lesbian.” I was a little unaware. But yeah, it was something that just sort of sat all around me. Constantly. And especially after I came out in high school and everyone in the school knew I was a lesbian. This was a school of almost 2000 kids, and I did not know any other out lesbians at that school. It’s not like people gave me that much hassle, but it felt like I was the only one that existed.

And that, in a way, is its own version of homophobia in that it was pretending that no one else here was like me. And even though no one threw that in my face, it was still constantly there. I knew this one other girl who was gay, but she graduated when I was a freshman. When she left, I felt this horrible sense of, “no! She was the one person I could talk to!” You know?

They were never going to say to my face, though. It was that southern politeness. They were never going to say “Get away from me, you gay!” But they were going to say, “oh, I’m just going to go over there…” I didn’t really understand these little micro-aggressions at the time and I’m still processing them. Girls would not want to be next to my locker or they’d need to move away from me a little bit.

And it’s hard. It’s still…it’s a funny position to be in. I’ve made a memoir, but at the same time, I’m still processing everything that happened in my childhood because I’m only 21. I haven’t figured it all out yet. I figured out a lot for this memoir, but there’s still plenty of stuff that maybe next year I’ll realize and think, “oh, that’s what was going on in high school.”

I think memoir implies that I really know what went on in my childhood, like I super get it, and I super don’t. I don’t. You know?

Walden: Of course. Of course. And that’s how most people’s childhoods feel, I think. When you think about your memories, they’re fragments. Some memories are bright, some are vivid, and some are dull. Some feel like maybe they didn’t happen, some feel like maybe they did. It’s complicated. And I’m okay with that complication.

Lu: We’re of a similar age. I’m 24. We grew up in a similar era, where the internet was coming to its prime, right?

Walden: Yes. We’re half-Internet children. It’s a really funny place to be, where we’ve lived in an era without smartphones, but then we also got smartphones at tender ages. At ages where we could be molded still.

Lu: I feel like that means something.

Walden: It does. I really do, I really think it does. And I don’t think anyone in our generation has really talked about that or figured that out yet, because we’re still growing up, right? So we’re not at that stage where we’re constantly reflecting.

Walden: Absolutely. Me too. There’s a repulsion I feel towards it, and maybe some of that is from the fact that we both had early days where that just didn’t exist in that space. So we know what it’s like to exist without that, whereas there are kids now who…there are kids who have never had it before, and then there are people who it came to them so late that they just don’t want to deal with it.

We’re at this halfway point. We can use it, we’re proficient, we understand it, but we know what a life is like without it.

Lu: At the same time though, growing up in Suburban New Jersey where you couldn’t get anywhere without a car, the internet was really important for my social development. I always felt like an outcast in high school. I was one of the only people into manga and was a total mall emo kid..that kind of thing. So I started making a lot of friends online because they got me in a way that those around me didn’t. Did you ever do that?

Lu: Right, you felt like you were being watched.

Walden: Yeah, I was being watched, totally. It wasn’t second nature to me to just put my thoughts into the internet, not yet. But at a certain point in high school, maybe tenth or eleventh grade, I was starting to realize I could do that. And a wealth of knowledge came to me that I never got from sex ed because they don’t talk about how women have sex! They just don’t!

They barely talk about how men and women [have sex] and that, to me, was such useless information. I was so angry. So the internet was a place to find knowledge and friends and people like me. But there was always a little bit of fear using the internet, even when I was talking to people that I thought I could like or could trust. I don’t know, maybe it was like all those videos we would watch as kids that were like, “don’t trust strangers! Don’t get in the white van with the candy.” There was some bit of that with me and the internet. Did you have that at all?

Lu: I did, I definitely did. I think I was a little bit different in the way that I used the internet, though. I’ve always been a boundary tester. I didn’t really have that fear of looking for things I was interested in. My parents pretty quickly realized that, so they set up firewalls to try and slow me down. But I also figured out how to dance around them. There are always sites that focus on these subjects that don’t end up getting caught by the firewalls.

Walden: Yes, of course. And there’s totally a moment, I think, for every kid of our generation when they realize how to use the internet a little more than they initially did. You could use the internet to do your research paper, but then there’s a moment where you realize there’s a lot more going on on the internet than you maybe initially suspected. And maybe every kid has a moment…I definitely had a moment where I felt like I went too far.

Walden: You get into too much of the dark internet. Then you see too much adult stuff or you realize that there’s so much going on that you don’t know and you don’t understand. And to me, that was like, oh my god, I have to step back. But maybe for other kids, it’s like, I need to step forward to understand it.

It’s freaky. But I think everyone has a moment like that. Actually, this is hilarious, I wonder … Maybe I shouldn’t say this, but a schooI went to…it turned out their domain name, with a bit of a different twist, could lead to a very different site. It also turned out that many people who went to my school made that error and constantly had this moment…

That, for a lot of us, was also a big moment because we realized schools have an internet presence. Our teachers have an internet presence. My high school and the administrators of our school board had Twitters. At one point in high school, I remember the whole school rallying to tweet at the board of education to give us the day off. And it worked.

We hammered this guy. We hammered him to get the day off on Twitter, and finally, our high school tweeted that, okay, we have the day off. Isn’t that insane? But it was also this funny moment of, “oh my god, our school is online.” It’s weird. It’s like you’re taking a building and giving it a life. You’re giving our school a voice, which is both wonderful and confusing. What consequences will that have?

Lu: Right, the fact that Wendy’s is a great internet personality freaks me out a little bit.

Walden: Oh, me too. It feels wrong in a little bit of a way.

Lu: Especially in an era where so much of the political conversation is also dominated by our efforts to demonize corporations and say that they aren’t people.

Walden: Oh, they are, they’re people now. They are, we made them people.

Lu: We love the Arby’s Twitter.

Walden: We do, and we love seeing them interact with each other. It’s fun. It’s bizarre. I would love to talk to more people our age about being a half-child. Anyone born in the 90’s, kind of, or maybe the late 80’s. What’s the cusp?

Lu: Even when you hit the late 90s, maybe 1998 or 1999, the line starts to get blurry. My sister was born in ’98 and she made a choice not to get a smartphone until she was 18, but all her classmates had them whereas I don’t think we did until we were getting towards the end of high school.

Walden: I think that’s an interesting choice. In middle school, everyone was on Facebook and I chose not to get a Facebook, which left me out of many, many loops socially. That was fine with me because I didn’t want to talk to anyone and because I thought it would waste my time. I was ever the little productivity giant.

And I get that, because I have plenty of social media addictions at this point, just not Facebook.

Lu: Right, right. We all pick a different poison, right?

Walden: Yes, we do. But for most of my friends, Facebook is still like their second voice. It’s like their second brain. It’s so strange to me and I’m so glad I didn’t get one. Because I’d be on it. I’d leave this interview and I’d check Facebook. And just because of that chance decision I made, I missed that moment of it getting deep inside me.

Lu: I guess the last question that I have is this: you’ve done a lot over the last few years. It makes you seem like you’ve been at this a lot longer than you have. And I think that’s a pretty cool thing. But was there ever a period in that year you took between skating and comics where you weren’t doing anything?

Walden: Yes. For a few months. I remember I wanted to be a high schooler because I never felt like a kid when I was a kid. And I thought I should try. I remember thinking I should try and be like a kid on Glee who just has normal kid problems. But I found it amazingly boring.

Still, I say it was boring, but I think it was also completely necessary and completely restorative. Even over these past couple of years, after I decided to devote myself to comics, there have been times where I didn’t really draw. People don’t realize this when they see the volume of work I’ve produced, but after On a Sunbeam finished, I took maybe two months and didn’t really draw. And I still am only just now starting to get back into working full time because I thought I needed to restore.

I can’t sustain constantly working. I also, it kind of drives me crazy when people say you should draw every day. Should you work every day? Should you go to your job every day? No! It’s the same thing, at least for me. My life since I stopped skating has had these punctuated moments of rest that have been essential to me being able to do what I do. Otherwise, how could I recharge?

Since finishing On the Sunbeam, the break I’ve had has been lovely. My wrist feels great. But there’s still this little burning in me that’s like, “oh god, I would love to wake up early tomorrow and work on something.” But I feel like learning to sustain in this career is about learning when to not listen to that voice and tell yourself, “no, you’re going to lie in your bed and stare at nothing today. You’re not going to think about comics and you’re not going to read comics.”

I’m still working out that balance of working and not working and finding my pace, because I’d like to do this for a long time. And if I’m going to do it for a long time, I need to not get carpal tunnel and I need to get 10 hours of sleep every night. I need to eat well and I need to exercise. At the same time as all that, I also want to work hard. So I have to find the balance between those things.

Lu: The fact that you know that you have to do these things means you’re probably going to last until your eighties or beyond.

Walden: I hope so, goddammit. I will not be a Tezuka and die young and tired. You know? No! That seems so painful to me. I don’t think comics should be painful.

Spinning is available now.