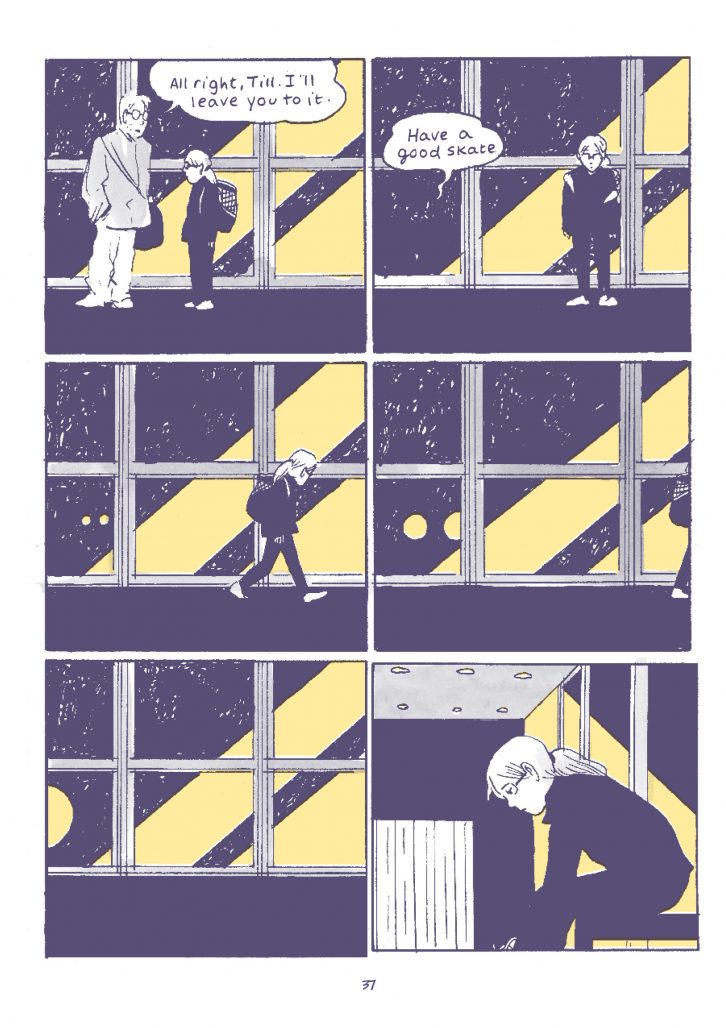

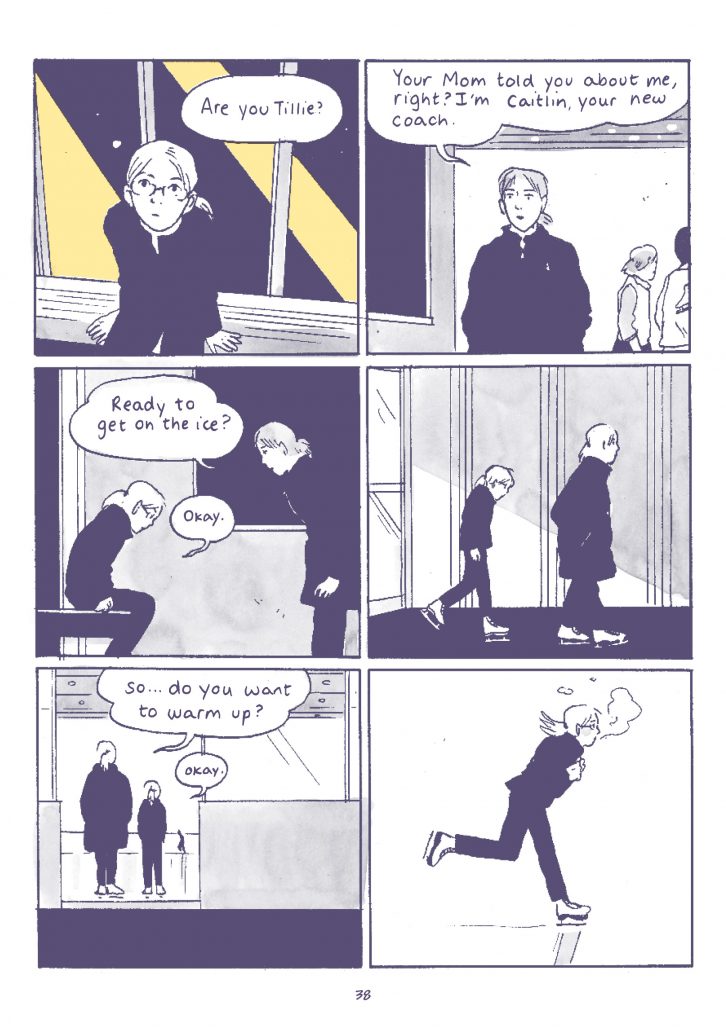

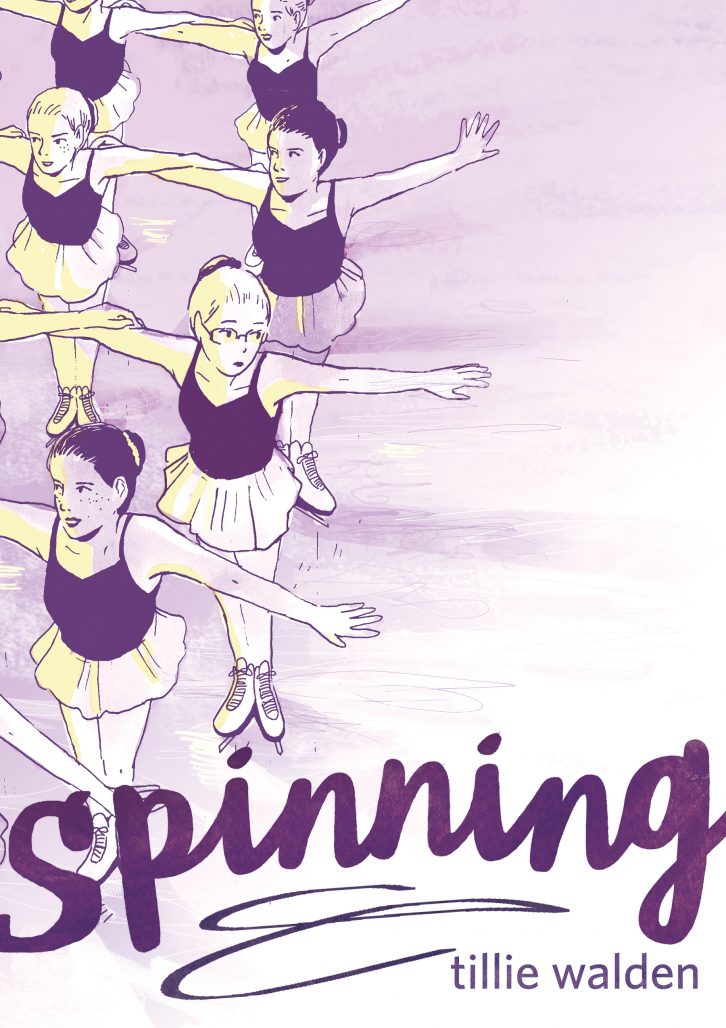

This week, publisher First Second released Walden’s first graphic memoir, Spinning. The book follows Walden throughout her childhood figure skating career. In it, Walden recounts the unique pressures she faced on the ice and off. Through various anecdotes, we learn how Walden was shaped by her childhood move from New Jersey to Texas, how competitive skating informed her approach to life, and just how complicated it all became as she developed her personal and sexual identity.

In the first part of this two part interview, the Beat sat down with Walden to further dive into how she was shaped by her move from Texas to New Jersey and explore the working methods that have allowed her to rapidly ascend as a working professional in an industry that many spend their entire lives trying to break into.

Tillie Walden: Definitely bigger crowds in New Jersey. Plus, the competition circuit for a New Jersey ice skater is much wider than that of a Texas ice skater. When you skate in Texas, you skate on an ISI system. This is getting kind of specific, but you almost only do competitions in Texas, and the crowds are very much the same at every competition. But as a New Jersey ice skater, every weekend I would go somewhere like Rhode Island, Colorado, or California and there would be this big USFSA audience. It was much bigger overall in New Jersey.

That said, although the audiences in Austin and in Texas in general were small, they were very enthusiastic.

Lu: It definitely seems like you have a skating subculture in Austin.

Walden: Yeah, absolutely. Austin was unique. And a very small community, everyone knew each other. It was like being at a small school or living in a small town, where everyone is in each other’s business a little bit. It’s just a little too close for comfort. Although some people liked it.

Lu: Honestly, I think it’s a little strange for Texas to have a skating culture at all.

Walden: I know. It’s very weird. In Texas, most of the skaters that I met were very Republican, very conservative, and generally, I hate to say it, but they were country folk. Very down-to-earth, they’ve lived in Texas for a long time— for generations, they shoot guns and they ice skate. They were often lower to middle-class people. And then in New Jersey, the people who ice skate are often wealthy, liberal, usually white, and are usually this kind of upper-class, east coast people.

Lu: I know you talk a little bit in the book about how, at skate competitions, you were expected to present as more and more feminine as you aged. Do you feel like the pressure to do that was the same in New Jersey as it was in Texas?

Walden: That’s interesting. Well, there were definitely similarities. But I think they were a little different. In New Jersey, the pressures always seemed much more focused on my skating and on our skating [as a group]. There was obviously a lot of emphasis on appearance still, but the focus was really on how you performed. In Texas, it really felt almost wholly based on appearance. Your skating was important, but in Texas, they took how you looked to a different level of seriousness.

The competition was also much more vicious in New Jersey. The teams had very personal rivalries— especially in synchronized skating. There was a lot of drama between all of them. But in Texas, because it was smaller and the competition felt a lot less extreme…I don’t know. It was just so different.

None of my friends who I skated with in New Jersey…I don’t think any of them have ever skated in the south. They’re very separate communities and they never really coincide. I would love to know what other skaters who have skated in both those worlds think, or if they’ve seen those differences because when I moved to Texas, I found it shocking that things were so different. I thought, “it’s just ice skating, it should be the same everywhere.”

Lu: Right. It’s a sport.

Walden: It’s just a sport, and you’d think sports would have regulations and rules and just general cultural things that sort of stay the same. But even the rules are different in Texas. Even the judging is different. The terms for different moves are different. I remember being so shocked when a girl in Texas told me the term for some move. So, in New Jersey, you call this move an intersection. It’s where these two lines of girls go together. And in Texas, it’s called a splice.

In New Jersey, the skating culture…I grew up with it. I was involved with it at such a young age that it was very inherent to me. I never questioned it. Then when I got to Texas and saw that it was different, it made me question what I believed in and what I thought I knew about ice skating.

Lu: When you were ice skating as an elementary school student in New Jersey, were people already hyper-competitive?

Walden: Oh, yeah. It was so competitive. Everyone was trying to be the best, and when everyone’s trying to be the best and have parents who are trying to make them the best too, it just leads to meanness. It leads to cruelty. And I just happened to have a lot of coaches who were very extreme in how they coached. That led to a lot of pressure. It was actually more extreme in New Jersey. When I got to Texas it chilled out and got a little nicer, but there was still pressure underneath it all.

Lu: Did you feel like that pressure was external or internal?

Walden: I think there was a little bit of external pressure, but it was hard to pick up on because in the south, someone will say, “How y’all doing today?” So there’s this politeness, but underneath it, you can tell that there’s more going on. So I felt like there was pressure beneath the surface, but as I got older, I think most of the pressure ultimately ended up being internal. What I expected of myself and what I thought I had to do. I thought I needed to do this sport, so I kept doing it.

Walden: Oh, absolutely. I come from a family of very talented people. My twin brother is an extraordinarily talented musician, constantly winning things and constantly being the best. I love my family to death, but we’re also a little competitive with each other, and there was just always this air that I had to succeed in what I did. It felt like that was right, because for the most part, I did succeed. I got gold medals often. And when I was in New Jersey, I was on this amazing team. It seemed to make sense that I wanted to be the best.

Lu: Being the best is already the bar, right? How does the bar get higher from there?

Walden: Because in skating, there is this desire to be the best and win, but there’s also this desire to look the part and be the most quintessential ice skater you can be. That means being thin, having the right hair, having the right makeup, and having the nicest dress. Ice skating dresses are so expensive and I was constantly wearing the same dress because we couldn’t afford to get new dresses for every competition. That’s insane. At least, it was for us. Still, there was always this burning desire in me, just wishing that not only could I win that gold medal, but wishing that I could be that ice skater with all those new dresses who looks the part and has a coach that wears the cool coach’s jackets, too.

I thought I really wanted to succeed in the visual stuff, but I don’t think I really did. I don’t think it would have made me happy to have a new dress. I don’t even think winning the gold medals made me particularly happy. I think the feeling of ice skating made me happy, and I didn’t realize that you could just want that. You could just enjoy doing something and not compete in it, you know? That was a revelation to me; when I realized that you could just do something for the love of doing it and not have it tied up in all these expectations.

Lu: That’s still such a hard thing for me.

Walden: It’s so difficult! Look at me, why am I at San Diego Comic-Con? It’s always this…you want to make the most money with your comics, you want to win the awards, you want a big audience, you want the page views. Whatever it is. You just want it, and it’s so superficial most of the time.

Lu: How does it feel to be 21 and have come this far already?

Walden: Bizarre. And it feels a little bit like I don’t have a lot of control in some way. I mean, these past couple of years have sort of spiraled for me. Upwards, not downwards.

It feels like it’s just out of my hands, in a way. Having an audience and finding success in this community feels like, I don’t know, something very distant and something that’s just sort of happening around me. I honestly don’t even know if it’s all really sunk in because I don’t know if I’ve been doing it long enough to deeply understand what’s going on. All I do know is that I’m very happy with what I’m doing, which is still a new concept to me. And every day it still feels like, “wow, I like my job. I like my work.” And since I quit ice skating, I’ve been nothing but happy, which is still kind of shocking. The success is like this extra good thing, but it’s still all very strange.

I mean, I just made a memoir, but despite that, I’m a surprisingly personal person. I’m pretty private. The comics that I publish are still for myself; they just happen to be read by other people. But it’s a very different thing to make something and look at it and keep it in your own room, away from the world, versus making something, dealing with how you feel about it, sharing it with everyone, and then dealing with how they feel about it. It’s a very different thing.

And I think I’m hesitant about that because with ice skating, so much of it became about what other people thought of me, and being stuck in this world, and I never want comics to be about other people. I want them to remain something that…you know, like ice skating just for joy. I want comics, at least for as long as I can make them, to be something that I can do just for joy; for myself.

Lu: It’s obviously that you work very quickly. It’s incredible and extraordinary that you could start and finish a project like On a Sunbeam so quickly. Is this just the pace you work at or do you feel like, as a professional, you’re forced to work at a slightly higher pace than you would normally work otherwise?

Walden: No, it is just the pace I work at. And I don’t even work all day. I usually work in the mornings and then I take the afternoons to do nothing or read or watch movies. I get a little ferocious when I draw, so when I start drawing, I get a lot of energy and the work just happens really, really fast. It feels really good for me to work in that way. I think part of the reason why is that I really miss the athleticism of being in a sport full time. You really just exert a lot of yourself [in sports], and I think part of me, when I make comics, is sort of doing what I did back then, but in a very different way because I’m not using my body. I’m using my mind and my hand.

I think there’s a connection [between comics and sports] when I feel this deep urge to work really, really hard on something. And then when I’ve done that and I see what I’ve made, it’s like euphoria. When I finished On a Sunbeam, it was like, “oh my god. I can’t believe I just did that.” It felt so good to work so hard on that and then have the fruits of my labor right in front of me. It felt wonderful, and then it made me want to do it all over again. Just to jump into something else.

Lu: It’s very clear that there’s a discipline, right? In your demeanor and in the way you talk. That sort of restraint and measured professionalism, in some ways, runs counter to what the creative culture in western comics generally looks like.

The word “comics” brings up this idea of a funny newspaper strip. It doesn’t really mesh with the word discipline so much in people’s minds. But to me, it’s a very serious art form. And I try to do this with a lot of respect for the medium that I’m partaking in, because I feel like I’m doing something that is important to me and to the people who read my comics. Yeah, I try to do it with a lot of respect and discipline. And that’s all from skating. You know? The coaches and that competitive lifestyle taught me how to follow orders, work hard. But now I’m following my own orders. So in a way, it’s a little easier.

Lu: The further we go into this conversation, the more professional skating starts to look like the military in my mind.

Walden: A little bit, but mixed with other different things. Coaches are very much surrogate parent figures and skating becomes your own version of home life because you live at the rink. I think it’s a pretty toxic sport and a pretty toxic environment for young people. I know a lot of people who quit skating and never want to skate again. There are also people who just want to skate forever, but there doesn’t seem to be a lot of in between.

I think I’m lucky because I think if I had skated a little bit longer, I would have been so put off by that kind of work ethic that I may not have worked on anything ever again. I quit at the right time and I was able to rest enough after all my skating. I had my last year of high school where I wasn’t skating at all and that was the first time I’d ever been in school where I wasn’t doing something before and after school every day. That was unlike anything I had ever experienced before. I remember sleeping in until 7:30 the morning after I had stopped skating, and it was this huge revelation to me that I could actually rest. Then, of course, I got so into comics that now I wake up at 4:00 and work on comics. But I enjoy it.

Lu: I’d like to return to the importance of appearance in figure skating. You said that one of your competitors dressed up as a Dr. Pepper can once. That seems like it would’ve been a glorious image to have in Spinning. What did you dress up as?

Walden: I did a couple things, I did Sesame Street on Ice and I was Cookie Monster. In Glee on Ice, I was Quinn, the cheerleader. And at one point, I was an airplane. I was a physical airplane! There were wings coming out of me, I had suspenders holding the airplane up, and I was maneuvering … And there were other airplanes on the ice with me. It was all just bizarre. I remember that airplane took up so much room, it was so difficult to travel with.

Lu: Why didn’t we see these more absurdist elements in the story?

Walden: I definitely thought about putting some of the more ridiculous stuff in the book, but the first problem was there wasn’t a lot of room. It was very difficult just to fit in everything I already wanted to fit in. More than that though, a lot of those memories of the more silly stuff like being an airplane, being Cookie Monster, and my friend being Elmo with me…those are cherished memories and I kind of like to have them for myself, in a way.

In a way, some of my memories are now more…I remember the scenes in the book more than I remember the actual memories, because drawing them feels a little bit like erasing the memories, in a way. So with some of the more silly stuff, I didn’t want to erase them so much. I wanted to keep those memories for myself.

Plus, they make good anecdotes for when I’m talking about this book. You had no idea I was an airplane on ice!

Lu: I had no idea. And now my opinion of you has changed entirely!

Walden: I really did not want to do that airplane thing. My coach totally pushed me into it. It was heavy and it was almost impossible to get in and out of the locker room with the airplane on me.

Lu: What was the idea behind it?

Walden: There’s some song about flying. It was some old-school song. We were old-school airplanes, the kinds with the bars, and I wore this pilot’s cap.

Lu: For a sport that seems so focused on beauty, this doesn’t seem graceful at all.

Walden: I mean, don’t get me wrong, even in my airplane costume I had to wear full makeup. Because god forbid you be an airplane and you don’t have lipstick on. And everyone really took this airplane thing super seriously. No one was laughing about it at the time even though I laugh about it now. But there’s an aspect of skating in Texas that is totally ridiculous. The airplane thing would never have happened in New Jersey because it was so serious. Skating in Texas, there were moments like this where we could let go a little bit because we were competing against other groups who were doing all sorts of other ridiculous things.

I feel like in skating, a lot of people forget that it’s okay to laugh at the ridiculousness of this sport. But it’s not something anyone ever really feels comfortable doing because no one really likes to judge ice skating when they are an ice skater. There’s this sense that “we are all doing this sacred sport and all the rules have already been written, so that’s how things are going to be. We can’t change anything.”

Look for part two of our conversation with Tillie Walden on Thursday. Spinning is available now.