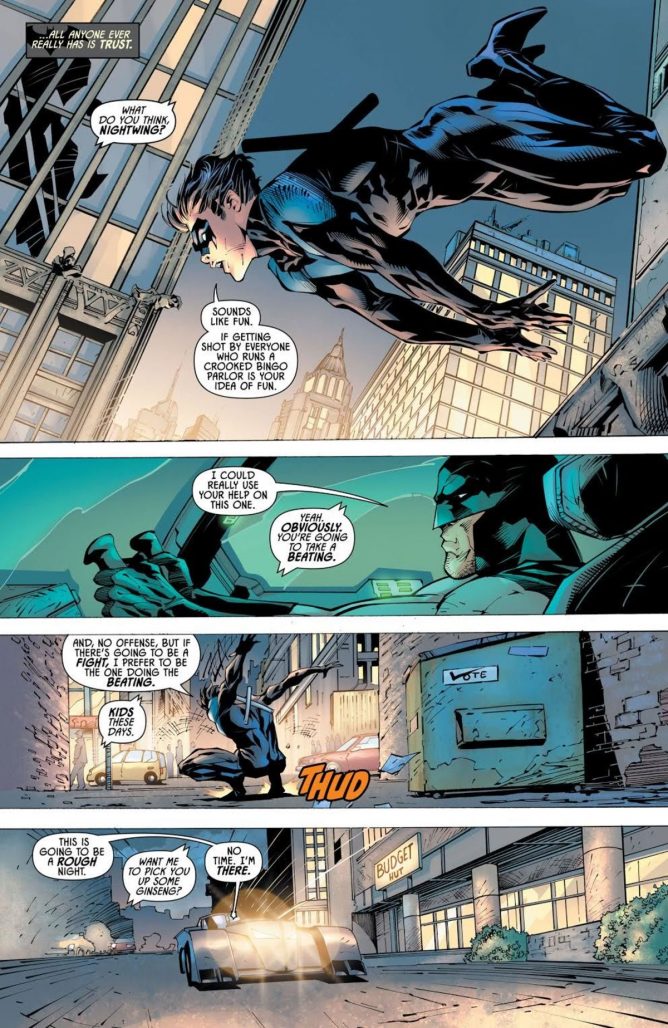

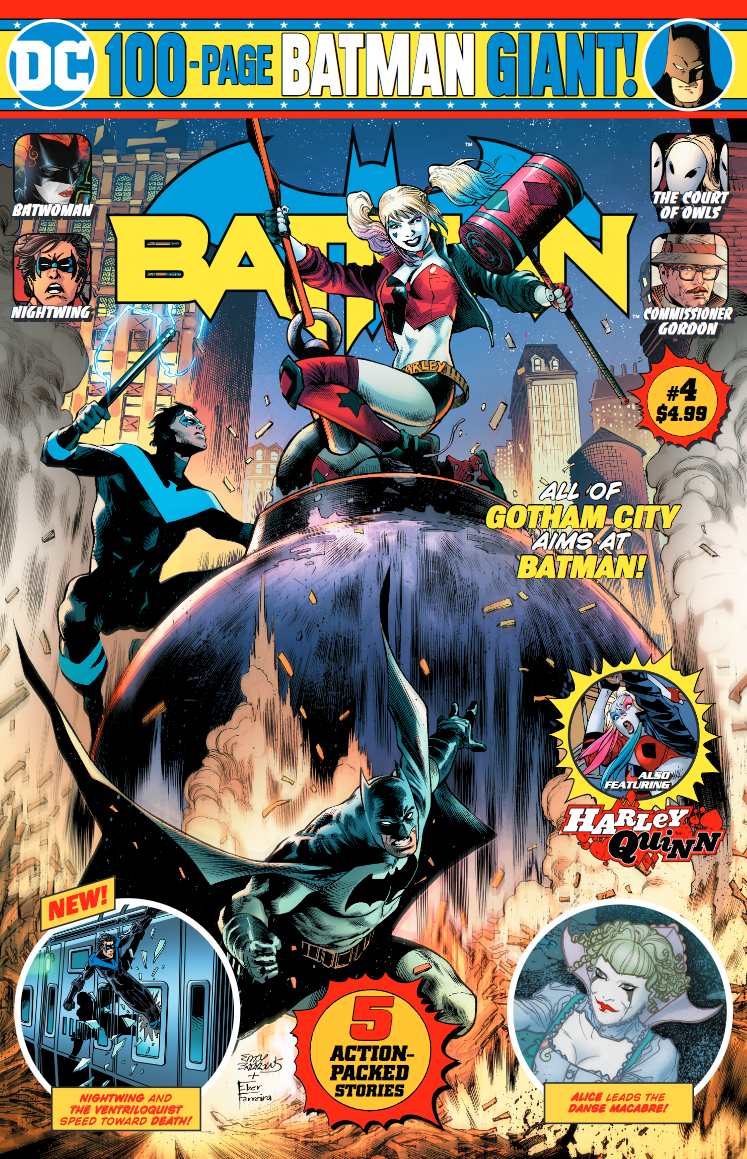

DC Comics return to comic shops this week with new titles after nearly five weeks. Among the publisher’s five-book slate is Batman Giant #4, the latest in their line of Giant books featuring reprints of classic stories and new, continuity-free tales. Writer Mark Russell, artists Ryan Benjamin, Richard Friend, & Alex Sinclair, and letterer Troy Peteri comprise the team behind the issue’s lead story, “Concrete Jungle,” which finds the Dark Knight helping Commissioner Gordon and the Gotham City Police transport a mob lawyer-turned-witness for the state across town to GCPD headquarters. Did I mention all the crooks and supervillains who want the guy dead?

The Batman tale is one of two DC releases from Russell this week, on the heels of Sunday’s debut of Swamp Thing: New Roots, a part of DC’s new daily digital release initiative. The story, illustrated by Marco Santucci, was originally published in print in Swamp Thing Giant #1 back in October 2019, and features Swamp Thing going up against the Sunderland Corporation, whose bio-engineered wheat poses a threat to all life in The Green. The tale also finds Swamp Thing struggling with a growing darkness inside of him as he tries to co-exist with the residents of the Louisiana bayou he calls home. It’s a comic that perfectly blends superhero adventure and elements of horror, with an ending that’s sure to leave readers wanting more.

Russell, also the writer of Billionaire Island and Second Coming from AHOY Comics, is one of the busiest writers in comics, and I was excited to get the chance to chat with him about his work on the latest Batman Giant, the challenge of writing a self-contained sixteen-page story, and what he thinks really drives the Caped Crusader to do what he does.

Joe Grunenwald: I know Batman appeared in Wonder Twins, but is “Concrete Jungle” your first solo Batman story?

Mark Russell: No, actually, it’s my third. I’ve done a couple others for the Giants. I think this is the first one that’s part of this new DC ‘digital first’ program.

Grunenwald: How do you approach writing a Batman story?

Russell: I don’t like to think, ‘How is this going to fit into the canon of Batman stories” or “How is this going to be yet another Batman story?” I kind of approach it the same way that I approach all my other stories, which is, “What is it that I have to say? What is it that’s bothering me right now that’s adjacent to this character, and how will this issue affect this character in the universe in which they live?” So I tend to come up with a story that I think will be relevant for that character.

Grunenwald: That makes sense, and with a story like this you’re not necessarily beholden to the continuity of what’s going on, and you can sort of do your own thing. Did you find that gave you a little freedom?

Russell: Yeah, I’m not trying to get from point 1.56 to 1.57 in the greater continuity. I’m free to just create a story that’s told completely from beginning to end, with no other repercussions on the Batman universe, in sixteen pages, which is liberating, and also I think gives you a better chance for success in storytelling.

Grunenwald: Is the sixteen page format a challenge compared to a typical 22-page or 20-page single issue?

Russell: Yes, ironically the less pages they give you, the harder it is to write the story, and sixteen pages is definitely a challenge. If I could write anything it would be those one-off 30-page mini-epics. Those are my favorites because you’ve got time to room out and create more of an epic story, but still a story with some urgency in 30 pages. With sixteen pages you’ve just got to get right in there and tell the story. You don’t necessarily have all the time to expand on the themes or philosophize and get lost in your own thoughts like I generally like to do. I have to get right into the meat of the story, and all of the sort of verticality and meaning that I want to put in there, it’d better be within the action of the story itself or it’s not getting in. So yeah, there is a challenge with writing a sixteen-page story, but in a way I think it helps to make the story leaner and a little more energetic.

Grunenwald: I thought the conceit of this story — a mob lawyer who it turns out was never a lawyer and thus not bound by attorney-client privilege — was really brilliant.

Russell: Yeah, it’s the sort of thing where, if I were doing a thirty pager, I’d do probably ten pages just on that part of the conceit alone. As it is in this sixteen-page story, it just sort of sets up the story to come.

Grunenwald: I would read a whole series about just that character and how they got to where they are. Did that come from anywhere specific?

Russell: I was thinking more broadly in terms of trust, and how much civilization is based upon trust. We have to be able to trust our neighbors, or the people who bring our mail. It really is this sort of unspoken trust with a thin layer of threat on top of it, because if you break someone’s trust, chances are you’re going to get sued or go to jail. But that really is the glue that holds our civilization together, is trust. The problems with running and underworld, in Gotham or anywhere, is that you are dealing with characters who are inherently untrustworthy, so what that would mean for being a mob lawyer or a mob defendant, the fact that you not only have to watch yourself constantly against law enforcement or vigilantes like Batman, but against the very people that are supposed to be on your side.

Grunenwald: Yeah, this is a guy who’s going to have to look over his shoulder, if he wasn’t already, for the rest of his life. That’s an interesting place to be.

Russell: Yeah, and I think, although I’m not very overt about it like I usually am, there’s sort of a broader implication that the more we give society and civilization over to con men and people who are untrustworthy, the harder it becomes to run those institutions that require our trust in those people.

Grunenwald: It’s interesting, because there’s the cop who wants to be responsible for bringing this lawyer in for various reasons, but then there’s Commissioner Gordon who says, ‘No, we have to trust Batman.’ Which is interesting because Batman is sort of inherently untrustworthy considering he wears a mask and operates outside of the law.

Russell: Yeah, it’s really about finding a situation where you realize then and only then who you can trust and who you can’t, and how ultimately the best superpower that Batman has is his ability to trust, in Commissioner Gordon, and Nightwing, and everyone’s ability to trust him. Without that trust, doing what he does would be impossible.

Grunenwald: This story also has you writing Harley Quinn again, though not in a starring role. You just can’t stay away from her, huh?

Russell: I love writing Harley Quinn. She seemed like a really ideal villain. Originally I was going to have multiple villains, but in sixteen pages you barely have time to do one villain justice, so to have all these other villains showing up was kind of too much, so I had to weed them out, but she seemed like the ideal villain to sort of carry the load for the villains in this because she’s sort of a creature of chaos. She’s sort of the embodiment of this sort of untrustworthiness that I wanted to be the overarching theme of the underworld.

Grunenwald: Yeah, and Harley is a character who sort of goes back and forth between being a straight-up villain and sort of an anti-hero, so she sort of plays both sides and you’re never really sure where she’s going to land.

Russell: Yeah, she’s sort of gone from chaotic-evil to chaotic-neutral. And she’s also a really good excuse to write some clever puns, so I tend to lean on her when I can.

Grunenwald: Aside from the Harley appearance, this story largely eschews Batman’s traditional rogues gallery in favor of nameless mooks and gangsters. It sounds like maybe that was a space consideration, but was there anything else that led you to choose to go that route?

Russell: Mostly just the space. If it had been thirty pages long I would’ve had other rogues gallery villains, but because it was only sixteen pages, and I wanted this to be a story about how the underworld as a whole is gunning for Batman, not just this villain or that villain, I had to focus in on one character to sort of be the standard-bearer for the villains, and then an assortment of characters that are disposable and that represent the generic underground of Gotham City.

Grunenwald: And they’ve got bazookas and flamethrowers, too, so they’re not exactly pushovers.

Russell: And nunchucks! Which has to be the most poorly-chosen weapon for an assignment of this kind.

Grunenwald: In Wonder Twins you had Batman and Superman going to see a movie called Gun Cop. Considering a gun took the lives of his parents, would Batman want to see a movie that spotlights gun violence?

Russell: I think if he wants to see a movie at all he’s probably going to be seeing one that spotlights gun violence, since that’s like 85% of the movies that are made for mass consumption. I doubt he’s going to see My Dinner with Andre when he goes out for a night on the town with Superman. So gun violence it is!

Grunenwald: Bruce Wayne’s a billionaire and a hero. You’re also writing Billionaire Island, where billionaires are evil. Why are you sending mixed messages about billionaires?

Russell: (laughs) It’s not that I think that billionaires are evil, even though this one or that one could be. I think it’s that a civilization that takes all of the resources to deal with the world’s problems and then gives them to people that have absolutely no incentive to deal with the world’s problems, that is evil. That is really short-sighted, and it’s probably what’s going to get us all killed. So it’s not that the billionaires themselves are evil, although the billionaires in Billionaire Island usually are, it’s that we’ve created a system where the incentives work against the better interests of the human race as a whole.

I think this is something that Batman kind of grapples with in some of my other Batman Giant stories, the idea that his identity puts him at odds with himself. On the one hand he’s this vigilante who’s looking out for everybody and is trying to bring order to Gotham and trying to help the people that are otherwise without a champion, but on the other hand he’s this great tycoon whose business is a great place for other villains to sort of launder their profits and invest them somewhere and clean the money they’re getting as they steal from normal people in Gotham. So it’s a part of his identity that I think he wrestles with, because he’s not just Batman, he’s also Bruce Wayne.

Grunenwald: Yeah, you see the argument every now and then that, if Bruce Wayne wanted to effect real change in Gotham, he would spend his money not on being Batman but on investing in the change that he wants to see in the world.

Russell: To be fair to Bruce Wayne, the problems with society are so macroscopic that it would take more than just one billionaire deciding to do the right thing to really effect change. We see this with Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk or these great philanthropists who will donate ten, fifteen billion dollars to fighting climate change or to finding a cure for COVID-19, and it’s really just a drop in the bucket. It’s the overall system, the pattern of distribution of wealth and creating these immense bubbles of wealth that go to very few people, that has to change if we’re going to have the resources to solve the problems that threaten the entire human species. It’s not just a question of getting one billionaire here and there to step up and do the right thing. So to be fair to Bruce Wayne, and ultimately Batman, he’s kind of the expression of the futility of trusting in one billionaire or one tycoon to do the right thing, because it’s not enough. That’s why I think he takes to the streets, because the billionaire philanthropy by itself is simply not enough. The problems created by the way society is structured are too great to be handled with philanthropy.

Grunenwald: I appreciate your really insightful answer to my stupid, stupid question. (laughs)

Russell: (laughs) There’s no stupid question, just some embarrassing answers!

Grunenwald: My last question is, what’s your favorite Batman story, and why?

Russell: For me, the one that sticks in my mind is “The Court of Owls.” It really puts Batman in a visceral state, and you really kind of see Batman at his essence.

Grunenwald: Yeah, he really goes through the ringer in that story.

Russell: I like stories with high stakes, stories where people are hanging on to the edge of the building by one hand and you start taking their fingers off one by one to find out, what’s the last thing they hold on to before they lose their humanity entirely.

Batman Giant #4 is due out in (operational) comic shops and digitally this Tuesday, April 28th.