The first time I came across a Maria Llovet comic book I remember thinking a lot about beauty, but not in the ways you might think.

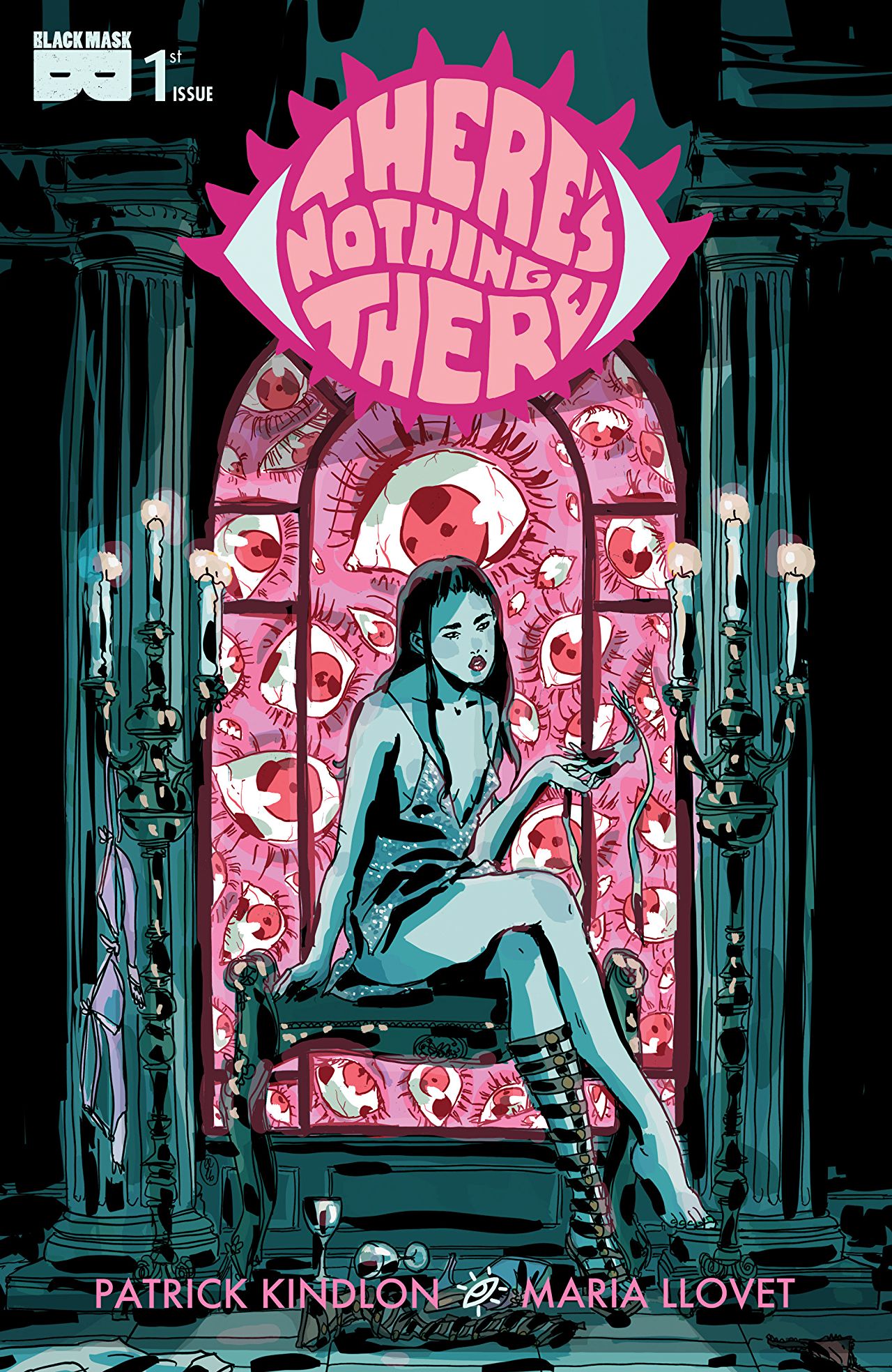

The book was There’s Nothing There, written by Patrick Kindlon and published by Black Mask, about a female celebrity stuck in between social media anxieties and an Eyes Wide Shut-like society dealing in black magic orgies. Four to five pages of the story in and I was already questioning the very notion of beauty itself, its agenda. It went from being a word we use to categorize things that are pleasing to the eye to being a force of indiscriminate destruction able to amass multitudes in its path. It even became a metaphor for the dangers of mob mentality, especially when coupled with sex.

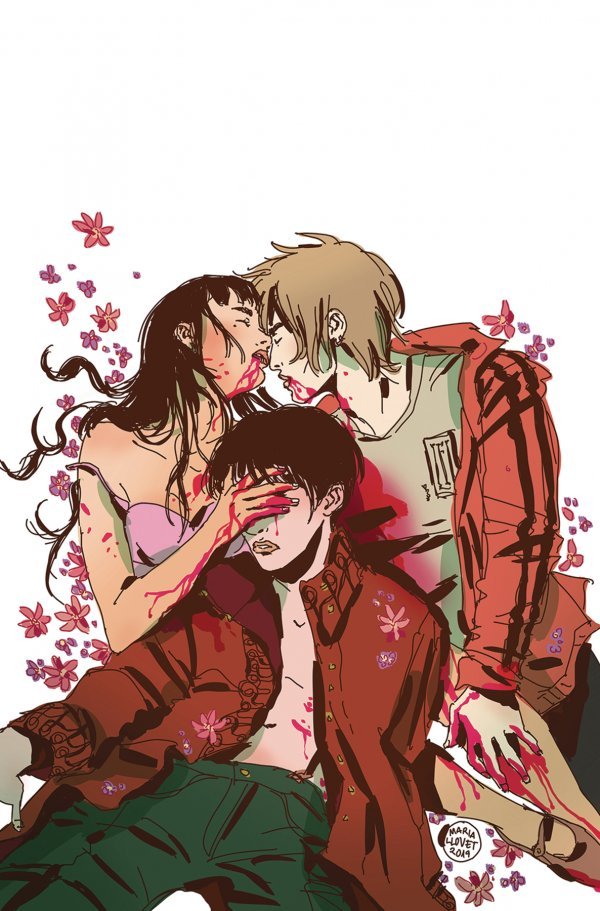

What was special about this exploration of beauty was in how it all came together visually, through Llovet’s fashion-infused, decadently erotic, and expressionistic character and background designs. Kindlon’s script made for a very complex look at sex, beauty, and ritualistic horror that allowed Llovet to get her signature style into the comics page in full effect. A style that continued to grow in BOOM Studios’ 2019 comic Faithless, written by Brian Azzarrello with Llovet on art.

Maria Llovet takes to sex and horror, drama and erotica, romance and violence in a very hallucinogenic way. Her compositions are delicately chaotic and bleed into each other to produce an aesthetic that feels like a fever dream laced with blood, magic and drugs. There’s a sense of looseness to how the action plays out in her stories, from start to finish. It says everything it needs to say on visual merit alone and invites the reader to approach the art with all senses on alert. It’s a very visceral approach to making comics.

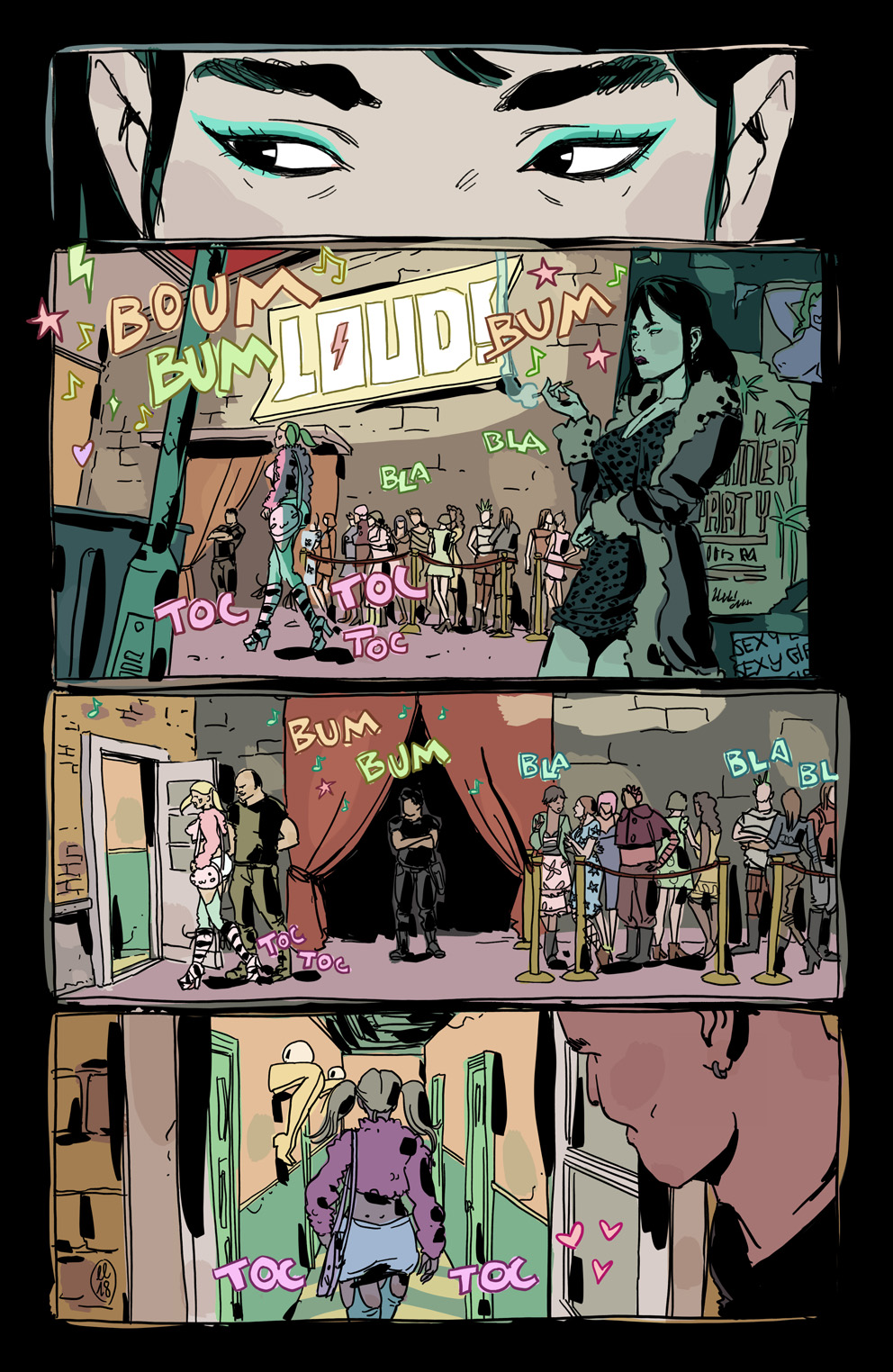

Llovet’s art style finds inspiration in Italian giallo color palettes, New Wave French cinema, and contemporary Asian film. Her inspirations, though, make way for an explosion of colors and a clever use of text and hand drawn onomatopoeias to give each panel a kind of kinetic beat, breathing life into every single pleasurably forbidden thing shown in the comics pages. It’s generously indulgent in all the right ways.

When elements of the supernatural break through into Llovet’s stories it all gets sucked up into the art’s sense of motion. The horror that comes out of these elements enhance the erotic parts of the stories and envelops them in a very seductive sense of danger. This is how Maria Llovet tells stories. Nothing is safe and we’re invited to dive headfirst into the fire.

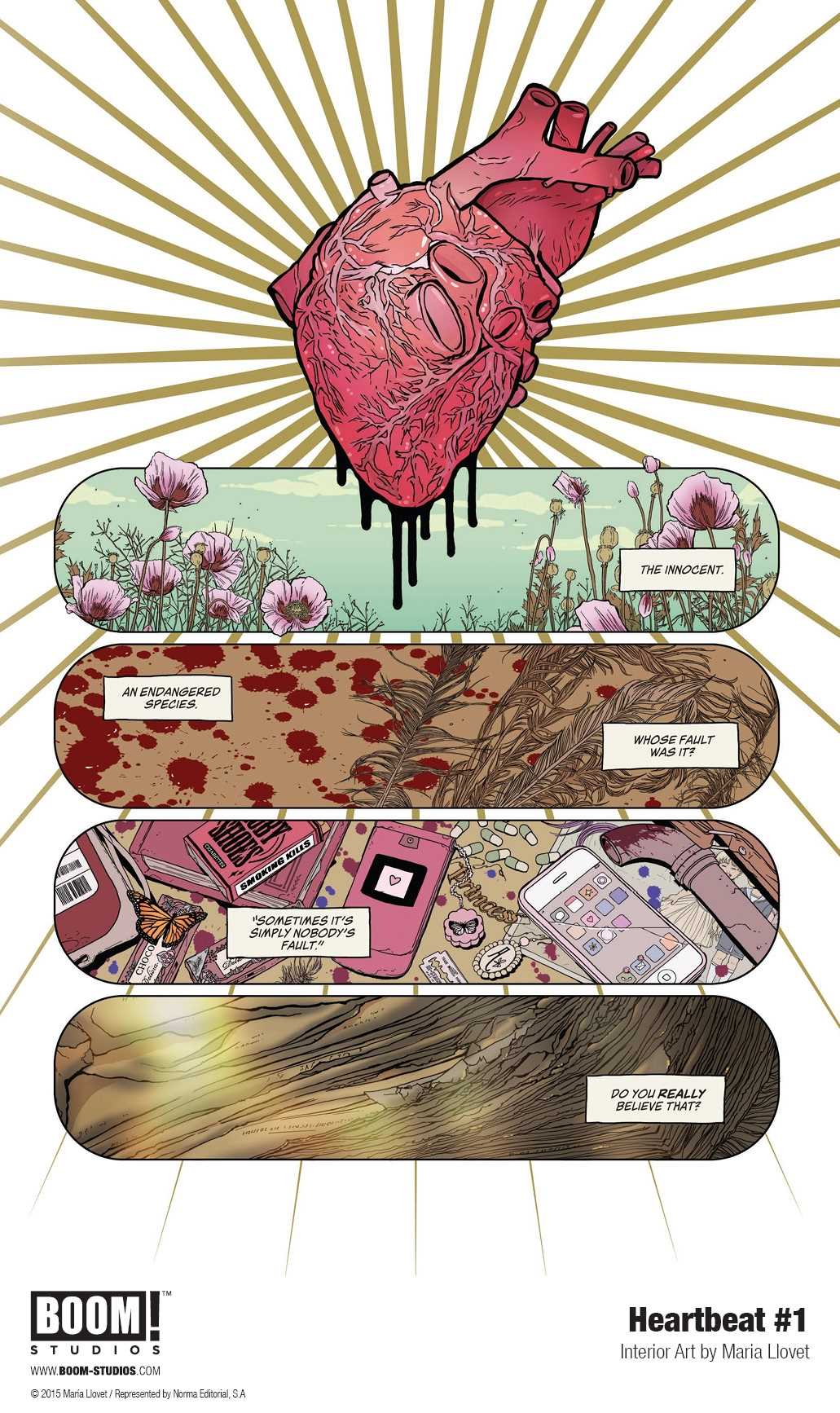

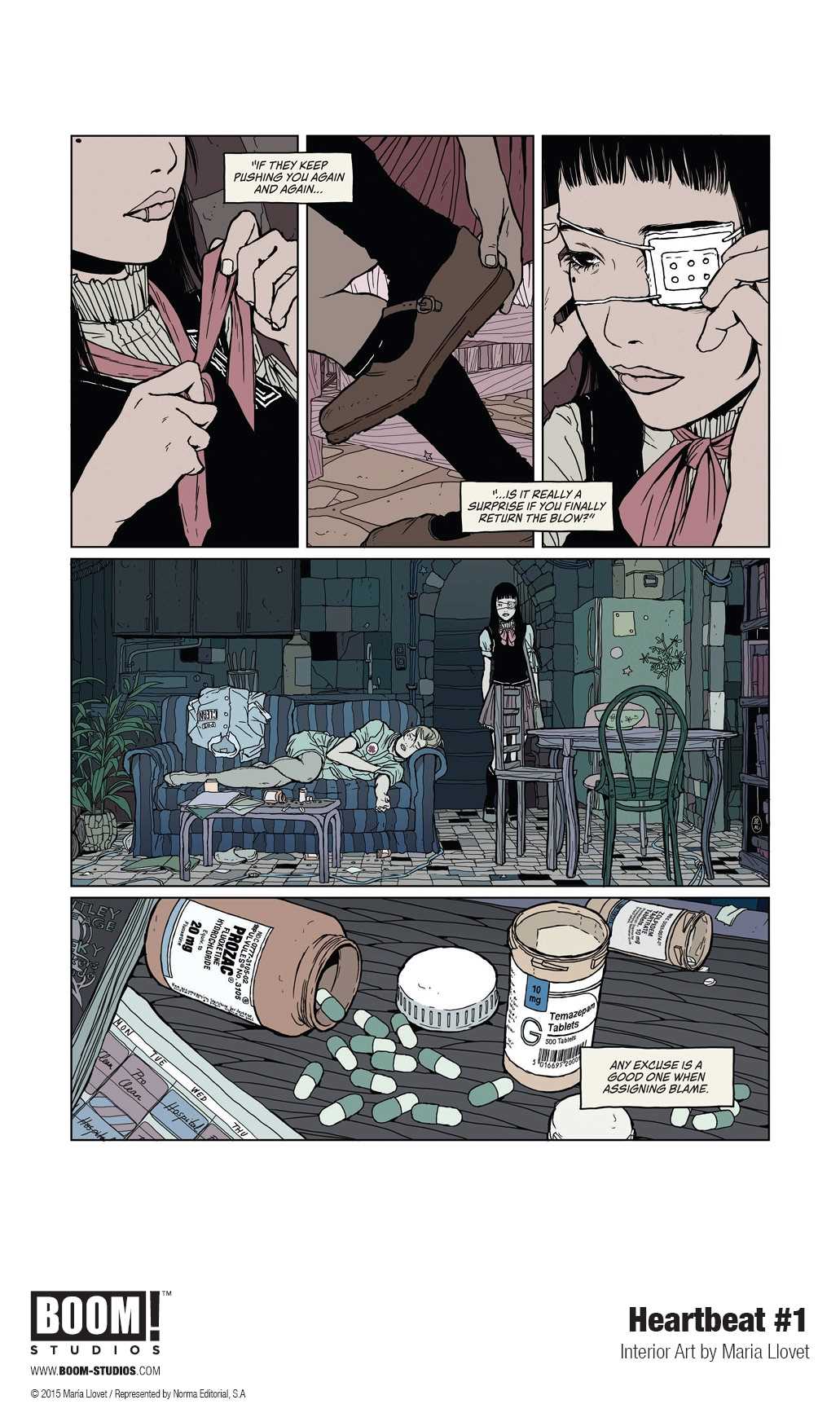

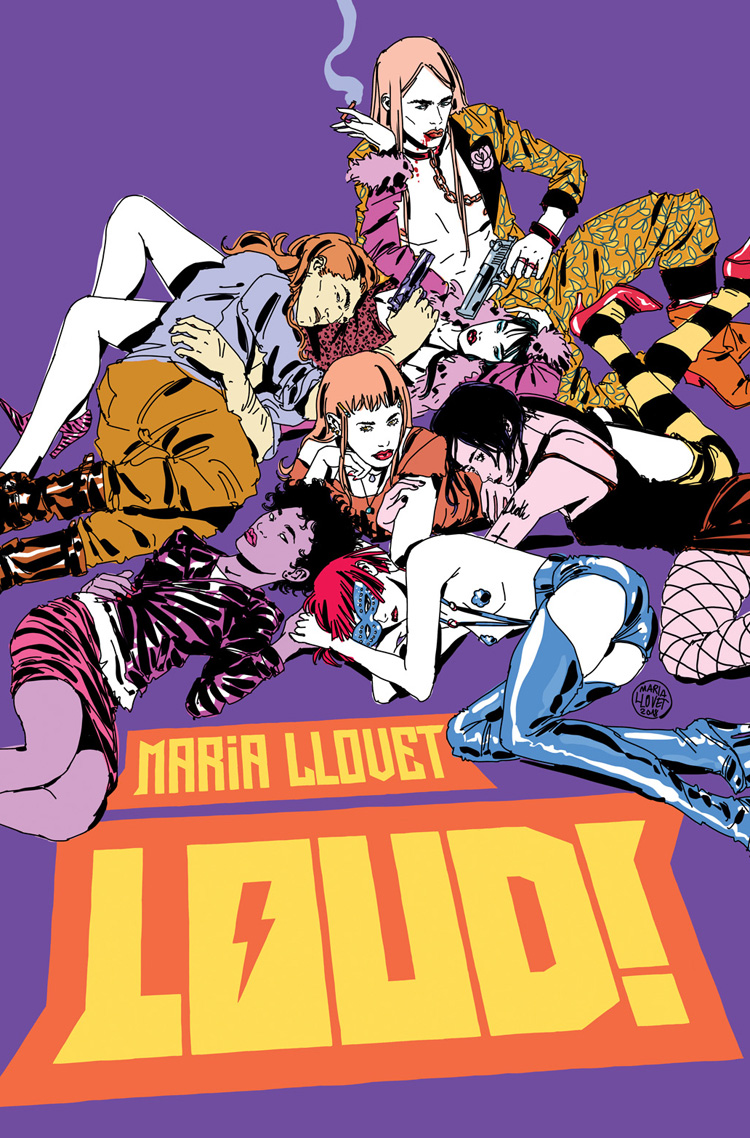

Llovet’s high school erotic horror comic Heartbeat is now available in English for the first time in its publication history thanks to BOOM and it’s being followed up with an original graphic novel called Loud, published by Black Mask (with a February 12th release date).

I corresponded with Llovet via email to discuss just what it is that makes her brand of erotic horror so unique to her and how her style has changed over time. The interview follows below.

(The interviewed was translated from Spanish into English by the author of this article.)

Ricardo Serrano: You’ve developed a very interesting visual style to approach comic book storytelling with. It’s visceral when it needs to be but subtle and expressive despite everything that’s going on in any given page. You can fully appreciate this in Loud, although you play with this balance in Heartbeat as well. How did you land on this particular style?

Maria Llovet: I think it has to do with the visual nature of comics and the great influence cinema has had on me when it comes to storytelling.

We could say comics occupy a space just in between literature and film, mostly because it can take from both forms while also resembling either one quite well (but always creating its own exclusive resources, mind you). The visual aspect of comics gives the medium weight. I love telling stories using images alone whenever I can, which requires a kind of base subtleness. The reader needs to be able to interpret those images and let them play out in their heads without walking them through every single part of the sequence.

At the same time I like experimenting with text and the most literary aspects of the writing. In Loud, text is reduced to a minimum expression given it’s mostly wordless. In Heartbeat, though, silence plays a different role, given it’s more text heavy. I love moments of silence in the middle of conversations. They can be louder than screams, or even say more than the text. Measuring one’s narrative through this type of resource helps develop a particular tone and results in something that’s just very fascinating.

Serrano: Heartbeat feels like a horror version of Romeo & Juliet where eroticism is played not for the sake of sex but of consequence. In fact, every sexual encounter tells its own story and affects the narrative significantly. What makes horror and erotica work so well together in your experience?

Llovet: As a reader, I don’t mind at all that a comic uses erotica or pornography to show sex just for the sake of it, as you say! If I like the style, and the illustrations seem pretty and attractive to me, I have no problem whatsoever.

Having said that, and speaking as an author, I prefer subtlety because what I’m interested in is desire and attraction. I find these topics fascinating and powerful. Love and sex are the motor which moves the world, and passion is the “fuel,” so to speak.

In terms of horror, sex is irredeemably rooted in death as a theme. Sexual awakening, the death of innocence, and fear (both of death and sex) are the questions of life. Love and death are linked eternally.

Heartbeat is a coming of age story with an inverted outlook given the journey itself is not the classical trip towards maturity. It is more complex and less defined. The relationship between the characters is toxic and ill-fated. In that sense, I feel Heartbeat is more psychological terror than just regular horror despite its dives into the macabre.

Serrano: Heartbeat creates a very unique type of ambiance which kept me intrigued all the way through. It’s not drenched in shadows and blacks. It’s clear line work that showcases the terrible and the violent in full color. What made you go down this visual route and were there any books or movies that inspired you in the process?

Llovet: What I knew I wanted to do with Heartbeat was show beauty in the things that are not considered beautiful, to show decadence and elegance in horror. I think I was highly influenced by the work of Suehiro Maruo (Dr. Inugami, Vampyre), which is macabre and decadent but also exquisitely beautiful. It creates a fascinating sensation when you see it and I think I was pursuing the same thing.

Thing is, I never thought I’d be focusing so much on horror, until one day I kind of realized it’s what I was doing. That’s why, I think, my stories aren’t really there to get you scared. It’s just that my work gravitates around those themes, without pretending to be full-on horror. I’m interested in distress more than fear, the same way I’m more interested in desire rather than pornography, as I was saying earlier. A sigh or a brief stare can say a lot if properly contained.

Maybe that’s why I’m obsessed with directors like Park Chan Wook or Wong Kar Wai. In these directors’ movies each situation develops in a subtle but extremely powerful way, in volumes.

I also like movies like Suspiria (the Dario Argento original), where terror comes coded with colors. It might be more traditional horror, but it’s fairy tale-like in a way.

Serrano: Let’s move on to Loud, which is fast approaching its North American release. We see an interesting change in visual style for this book. Whereas Heartbeat has clear and clean linework, Loud is more kinetic and chaotic. What led to this change?

Llovet: The truth of the matter is that it was Heartbeat that inspired the change. The book was published in Spain back in 2015. It was a lot of work to push that into the market for various reasons. There was a lot of self-questioning. I hit several pauses along the way. When I finally finished it, I wasn’t happy with my style in general. Looking at it from a distance once I was done with it helped me determine what I didn’t like doing and what I wanted to do more of.

Despite all of that, I do see things I’m really happy with, especially in terms of storyboarding and narrative. I gave that a lot of attention and I can now say the book holds a special place in my heart. I’m very happy it’s reaching American markets now.

After Heartbeat, my next book, Insecto, was a kind of inflexion point where I started experimenting with inks way more than before while going a bit less restrained with my strokes. It felt like going back to my roots but with a better sense of narrative and technique.

Little by little I started to break free and went straight to experimenting with brushstrokes that were even more ‘down and dirty.’

I wrote Loud in between that experimental phase, but just as I was about to start working on it an opportunity came up to work with Patrick Kindlon on There’s Nothing There. It was my first American publication, but it was also my first book with my new art style.

After that, I started Loud. It took me a while to really dive into it due to other opportunities that had come up thanks to There’s Nothing There. It felt like I had lost the initial drive a little due to it being put off for so long. It took me a while to reconnect with Loud, but I had already put too much imagination into it and I powered through.

My new, more loose style needed time to grow too and I kept adjusting it over and over. I’m still adjusting it. It’s just easily mutable and it remains in constant motion. I do feel I have found the right way to illustrate according to my interests.

For a long time I felt like I was walking in circles, not knowing how to advance. But I think that worry is long gone now.

Serrano: Loud feels like an anthology of short stories all developing simultaneously. You go through so many different genres, experimenting with form and symbolism. Was Loud originally conceived this way or did it become that as you worked on it?

Llovet: It was always meant to be that since the beginning. With Loud I wanted to get experimental. The original idea was to go entirely textless given the music in the bar is so, well, loud that no one can hear anything. I modified the idea so that in those parts of the bar where the music’s not so loud I could add some dialogue in a very natural way. It allowed me to keep the story mostly text free, though. When I started I actually wanted to have the story flow like a single sequence, jumping from character to character but in constant movement. The fact of the matter is, as much as film and comics have in common, they’re not the same! I had to accept comics don’t move! But it was interesting stretching the limits of what the form can and cannot do.

In my other graphic novel, Insecto, I experimented with mosaics, trying to get them to look like they were gyrating around the characters. It created an interesting effect even if it wasn’t spiraling.

Although Loud is a pretty sordid and decadent story, it also has a festive tone to it that I had never explored before in my work, which tends to be quite moody. I was hungry for experimentation and what came out was something very much my own, in line with my previous work, visceral and intuitive.

Serrano: As a comics creator with an expertise in horror and erotica (and their possible combinations), what type of story within these genres would you like to see more of or see less of?

Llovet: This is a hard one to answer. It depends on the story and the author, really. Something that one might find magnificent in one movie, for instance, can result in something you hate elsewhere. There are no universal story ‘laws.’

Ultimately, I do recognize I care a lot about the internal coherence of the story. If character decisions fall in line with who they are and what’s happening in the story, regardless of how delirious or crazy they end up being, I’m for it. If they do stuff because they “have to” or because it’s “their turn” so it can serve a message, then you get transported out of the story.

Still, if you connect with an author and his or her work, you’re going to read them and you’ll probably enjoy them because the way they tell their stories makes you feel at home.

Serrano: Thanks!

Llovet: ¡Muchas gracias!