When the Indigenous Comic Con debuted in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 2016, it was part of a multi-faceted effort that included Dr. Lee Francis, who has been called “the Stan Lee of Indian Country.” Francis, a former teacher, also helms publisher Native Realities and Albuquerque store Red Planet Books and Comics as part of his effort to promote Native American comic book creators.

But this year, everything is changing. The Indigenous Comic Con proved so popular that it’s expanding and fulfilling another level of Francis’ ultimate vision by becoming Indigipop X. It’s not just a larger comic con anymore — it’s a week-long cultural festival running in Albuquerque November 5 through 10, featuring Indigenous innovation technology, film, television, music, food, wrestling, you name it.

Francis sees it in terms of SXSW in Austin, TX, and an outgrowth of ideas that were beginning to be explored in last year’s Indigenous Comic Con, when wrestling was introduced to the mix, as well as Native fashion and food. In regard to the latter, the festival featured a Native chef to present related cuisine within a modern foodie context. IPX will do the same with four chefs.

IPX will end with a music festival, but stay true to its comic con roots by offering a one-day, mini Indigenous Comic Con.

But that’s not all for Native comics gatherings in 2019. For a full comics convention experience that also wraps in other aspects of pop culture, the Denver version of the Indigenous Comic Con will debut on July 26, a weekend event known as Indigenous Pop X Denver, co-produced with the Denver American Indian Commission.

There will also be the Indigenous Comic Con in Melbourne, Australia, starting November 29. This weekend con will include Indigenous comics creators from Australia, New Zealand, and the United State, with the purpose of inspiring young people to create their own content and build communities of Indigenous cartoonists world wide.

What Francis calls “the Indiginerd Realm” is definitely having its moment.

———-

What was the inspiration for starting the Indigenous Comic Con?

A lot of the times native folks like myself end up going into these spaces where we’re the only representation, right? So when I show up at a comic con or when my colleagues show up at a comic con in our local areas we’re the only native people that are there. We wanted to showcase something where it was just all native folks in this space so rather than being tokenized in a way, although I don’t think that’s the intent of anybody. I think it’s very open and generous in many of the comic cons we’ve attended, and many of these festivals. But we wanted to create a space that was just strictly and solely native, and people could come in, and they’re like, “oh, this is an innovative event. That’s cool.” And that’s what we’ve been looking at doing

We wanted to bring all of these Indigenous and Native creatives into one space, that we’re operating in a pop culture world that often views Native people in historical context and only historical context and one in which Native and Indigenous peoples, they ceased to exist at the beginning of the 1900s, the era of the American empire. What we wanted to do was just showcase that Native folks are doing some really incredible work in multiple spaces — Indigenous futurism — and my work and my family is from the Pueblo of Laguna out here in New Mexico. So that’s my Indigenous background here. I’ve spent my years in education wanting to provide something for Native young people in Native communities that we’d be able to showcase in one festival, in one event, the amazing talent. There’s this broad vision of what Native identity is that is not captured in American pop culture in general.

So I had an opening in the schedule in November of 2016, and I was like, cool, we’ll do it then. I started putting everything together and contacting people that I knew and getting in artists and creators and comic book people and all the rest, and we put on the festival, and it was great. We had I think 1200 people in attendance the first year of Indigenous Comic Con. And we’ve had about 1500 people over the last two years that we put on the event. So it’s been really popular.

Indigipop X represents a major expansion from the original idea for Indigenous Comic Con, and seems like a huge vote of confidence in Native culture’s wide appeal.

In a way, yeah, and there’s a lot of people who have started to gravitate around that, especially here in Albuquerque because we have such a high concentration, probably the largest concentration per capita, about 10% of native people that live within the Albuquerque area. So we wanted to make sure that that’s also represented within our own space as opposed to other locations. We’re enough of a metropolitan area where native folks exist, but small enough where you can get a really good concentration of people and large enough in terms of representing the native communities from just the 21 native nations that are here in New Mexico, — Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache. It gives us a great base to grow off of and really showcase that talent. So that’s what we’ve put together.

We have support from the city of Albuquerque. We have all of these great supporters that have been looking for something like this because there’s nothing like this in the world. And that was also the whole impetus of starting to comic con in the first place as well. We wanted to be able to showcase all of this work, consolidate all of these people in one location over one weekend when we initially started because nobody else is doing this kind of work currently.

There have been some progenitors for this. There was a comic con way back in the day up in Canada. We have still been trying to figure out like who that was, who organized that. We’re still trying to find the history and ImagineNative out of Canada does really great stuff around like video gaming, VR work, technology and avant-garde futurism type of stuff. They do some amazing work, and we had them here this last year because we want to try and partner up with all these folks.

What did the Native comics community look like before the Indigenous Comic Con started? How did these books get distributed? How did people know they were out there prior to the con?

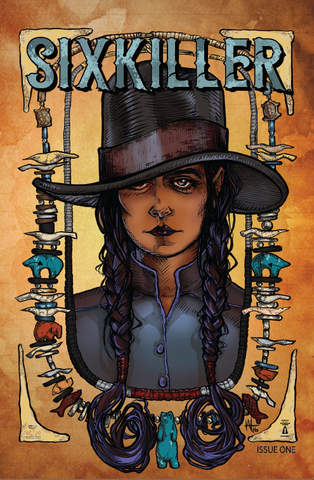

It’s been really local. Every now and then it would pop up into a mainstream or a big enough publisher that they could really distribute. But a lot of this stuff that was happening and that continues to happen is hand over fist, right? Like it’s a Native comic creator that selling their stuff in their local community. Maybe they’re getting a couple of books into some comic shops, maybe they’re getting a little bit more widespread exposure every now

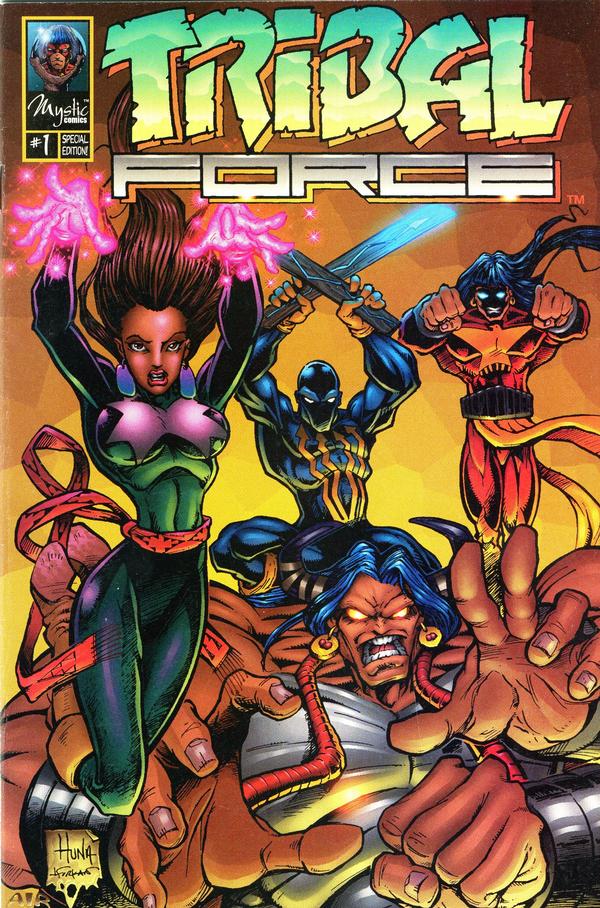

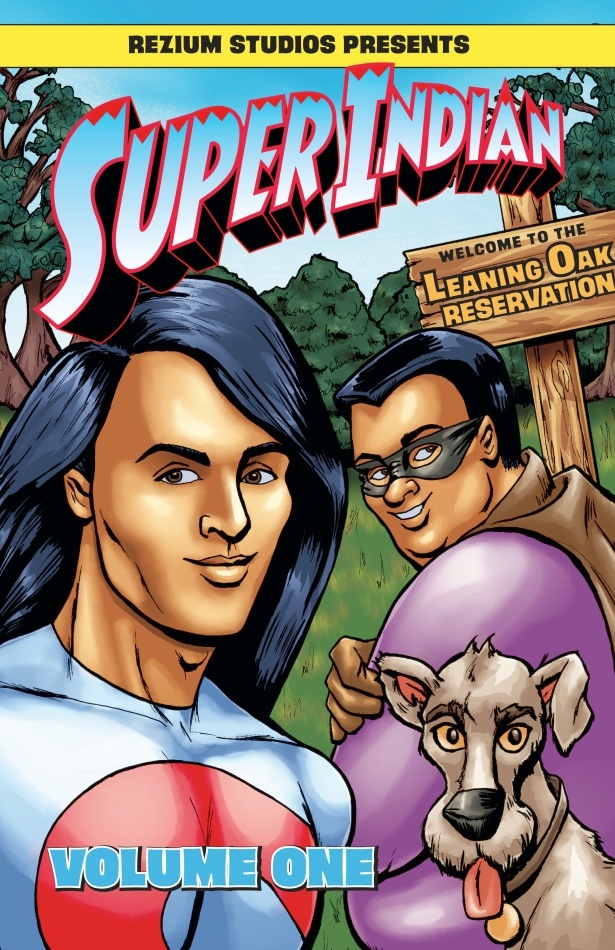

So it was Native post-apocalyptic, or Indigenous futurism, and Tim was doing that in the mid-80s. Jon Proudstar came along in the mid-90s, and he had a nice localized reach. He had a broader reach for Tribal Force, which was the first Native superhero team in the traditional superhero team style. He did that in the mid 90. And then Arigon Starr started doing Super Indian in the early 2000s, and she had the longest run. She’s up to volume three at this point. She puts out a new comic every Monday on her website.

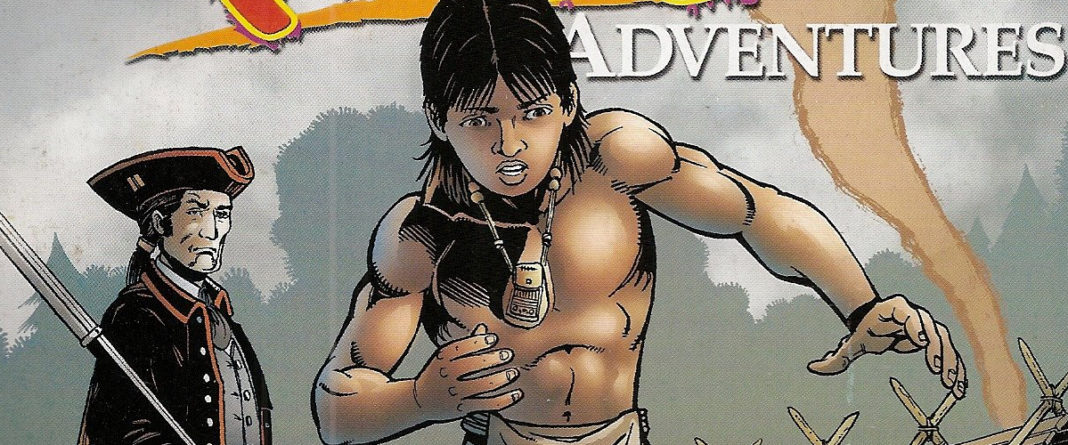

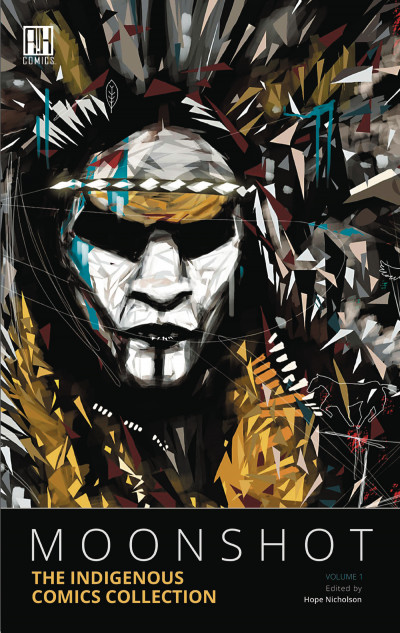

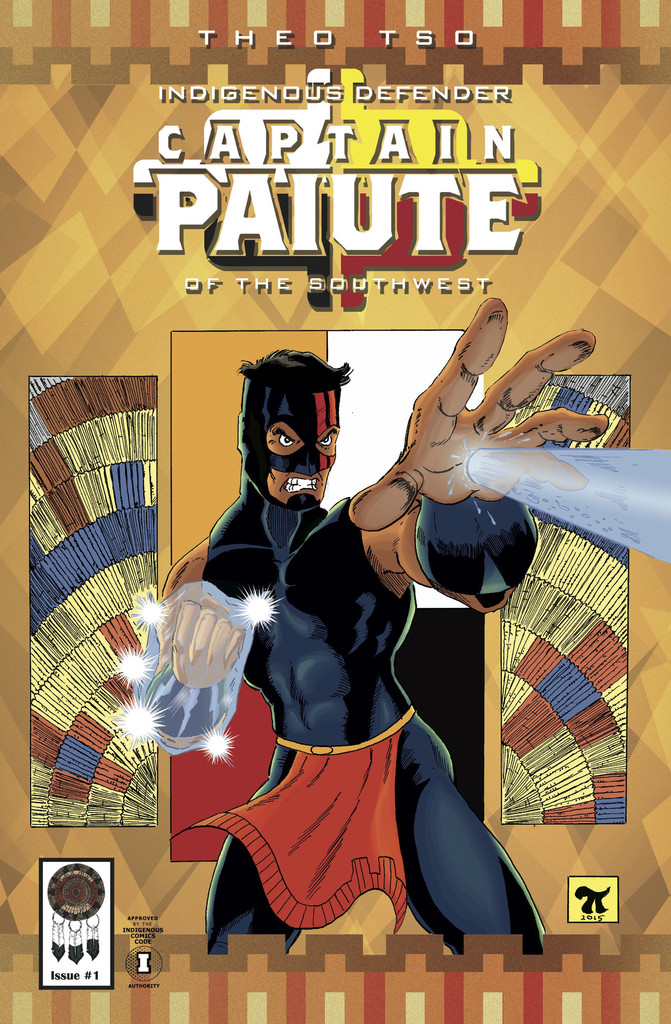

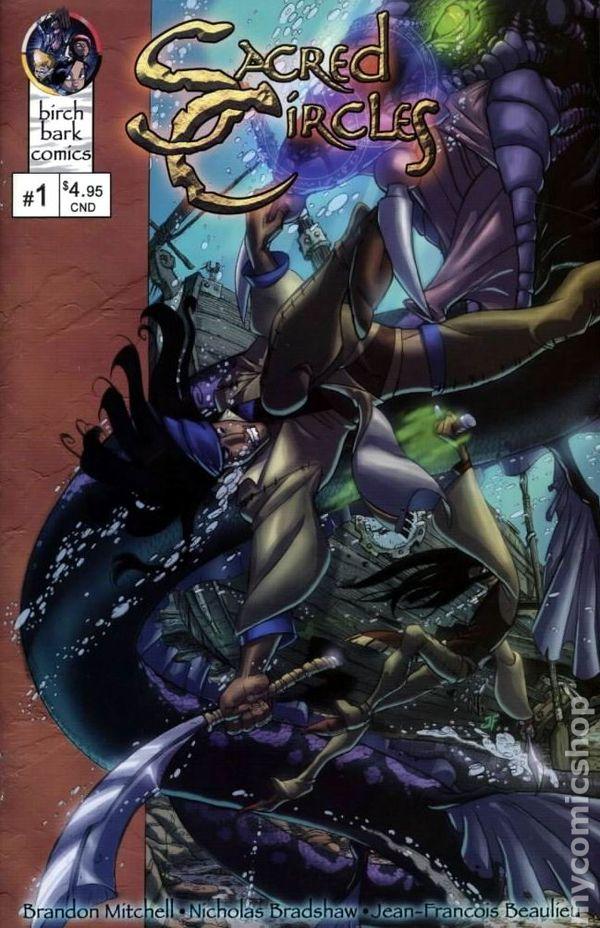

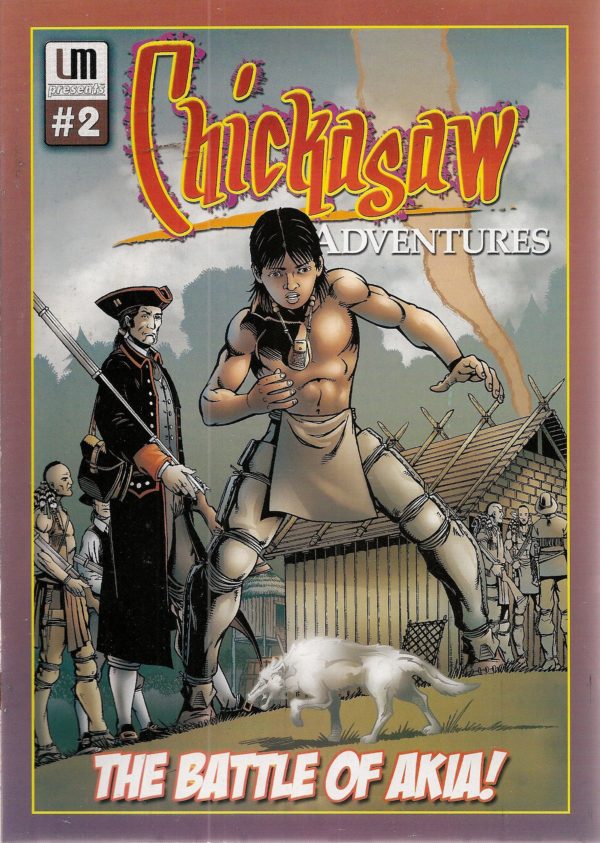

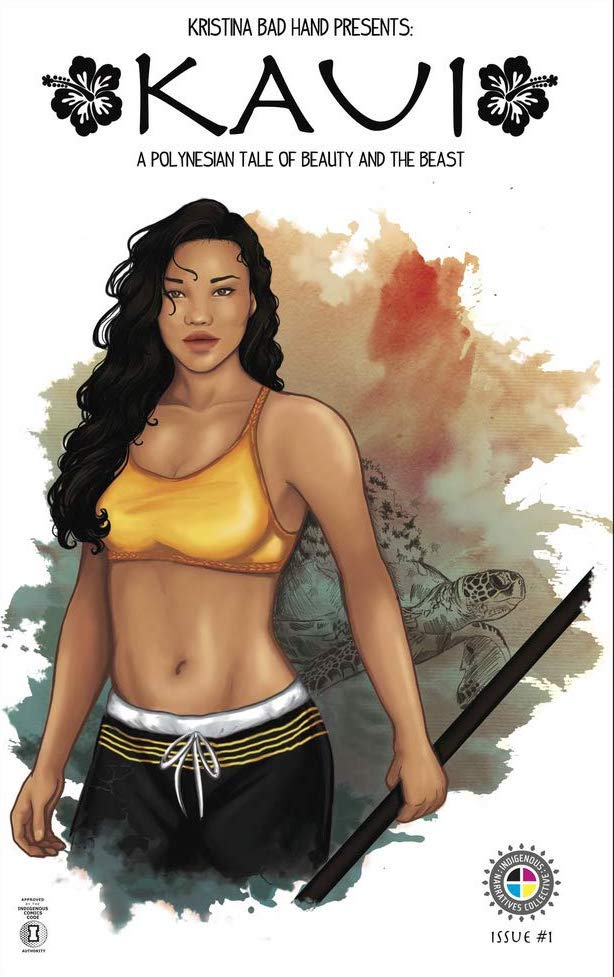

So there were all of these folks and then you started to see a little bit more. You’ve got Theo Tso doing Captain Paiute, you’ve got Kristina Bad Hand doing Kaui. You’ve got Sacred Circles by Brandon Mitchell. The Chickasaw Nation puts out Chickasaw Adventures, about a time-traveling Chickasaw kid. You’ve got some amazing scholarship work that was done by a fellow by the name of Michael Sheyahshe who did the book

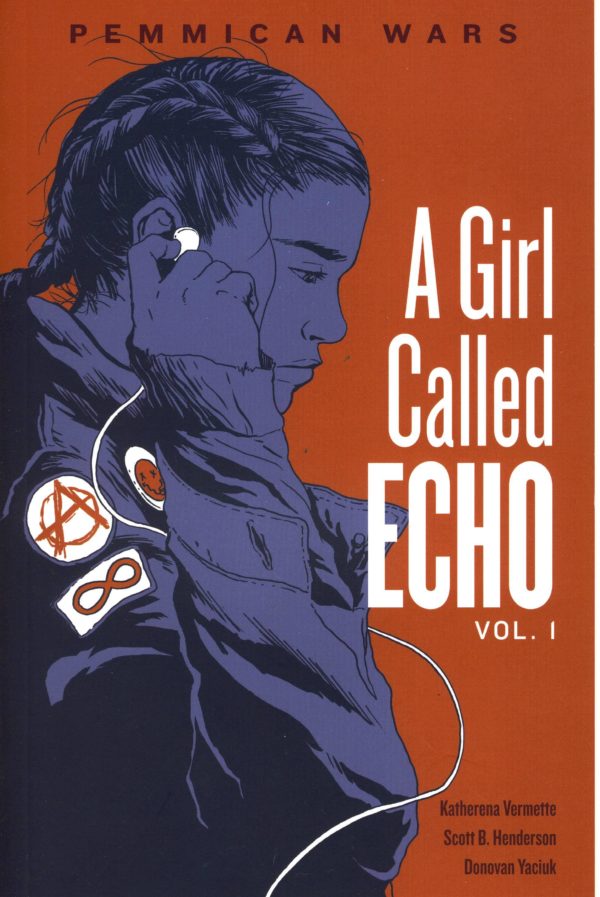

And then there was a bunch of stuff coming out of First Nations Canada, like Pemmican Wars (A Girl Called Echo) from Portage and Main. They’ve been doing some stuff through Aboriginal Health Network, more of an educational type of approach for Native communities up in Canada and First Nations. And they have a pretty broad distribution. So you’re seeing more of that.

You’re actually seeing a lot more north of the border than in the United States. So when we put Indigenous Comic Con on, and actually when we started our publishing company, the whole idea was to get more stuff produced here in the United States that was representative. And so we worked with a lot of these people, and we work with distribution. And so we’re trying to provide a lot of that, getting it into the mainstream line.

What’s been going your own publishing company, Native Realities Press?

This November we have a few others on deck. We’re still working through the development and illustration process, but the one that’s probably going to be up the quickest is called Ghost River. That’s a collaboration with the Library Company of Philadelphia to tell the story of the Paxton Massacre outside of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where a group of frontier settlers pretty much wiped out the last of the Susquehanna people in eastern Pennsylvania.

Is it a fictionalized history? Or are you doing straight nonfiction?

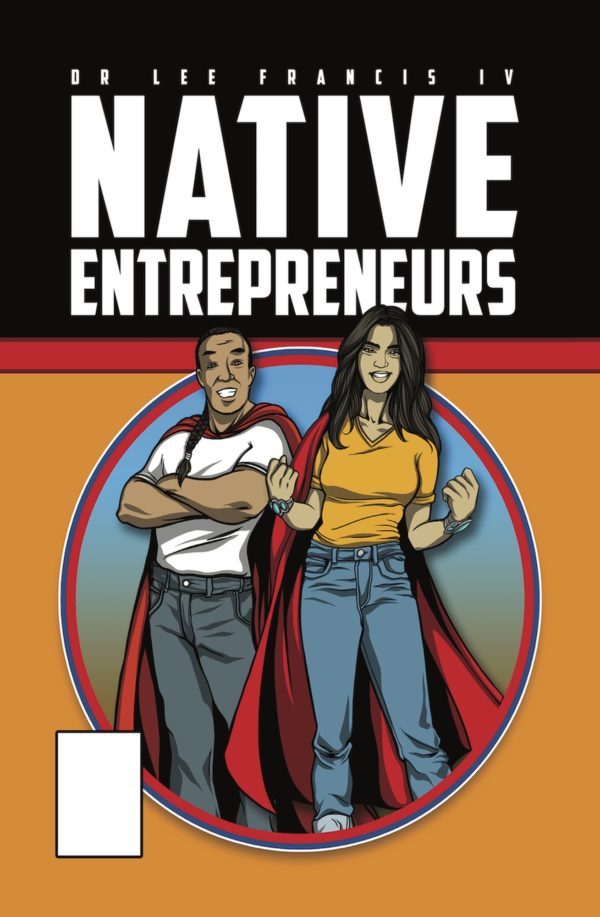

Mostly a fictionalized history. The entrepreneur one was based on actual stories that we got from Native entrepreneurs that we moved into a comic book space and created those stories around, around their work. Ghost River is historical, but it fills in the gaps because the Native history side is not recorded. So what we’ve been trying to do and what I think have we have accomplished is being able to tell the Native perspective of the story while we weave in historical aspects. So I would say it’s more history than it is fiction. It’s historical fiction history, for lack of a better term, because we don’t have enough of the Native narrative. We’re rebuilding that narrative because Native people have not been included in history very often outside of either as props in terms of the Grand American expansion or foils to the Grand American expansion, i.e., the Western tropes and motif.

I know that when you were a kid, you were big into superhero comics. Was that a singular pursuit or did you have a community that you were part of when you got into comics?

I would say it was a singular pursuit, but I definitely bridged across not only comics but any sort of the nerd variations. So I was into fantasy and Dungeons and Dragons and all of these other nerd pursuits. I think it comes from my dad because my dad was very much into science fiction and fantasy in the house. He was a big old sci-fi head, going back and

There came the point in his life where he would literally have to look at the copyright date because he had read so much, so many science fiction books. He didn’t even look at titles anymore because the titles would change and were still in publication so he would just look at the copyright date. He was like, “if it came out in the 80s, I read it.” He would get into this thing where he would start buying these books, and he’d get like three chapters in and be like, “man, I already read this one,” because they just change the cover. Whenever I would buy gifts for him, if I bought him books, I would have to look at the copyright, and it was like, “this came out last year. All right. He probably hasn’t read this one. ”

So my household was filled with that as well as Native literature and histories. And we had big bookshelves. So my dad was a big literary guy and understanding Native lit as well. And we come from a family of Native literature, a literary family, so that was a big thing. I fell into it fairly naturally, and comic books were never scorned in the house. I hear all these stories, “well, my parents never liked me reading comic books. They were like funny books for kids.” My dad was just happy that I was reading. So he’s like, “yeah pick up a comic or two, go ahead.” So that’s, how it would work. And then I wanted to read fantasy and I liked dragon, so I would read dragon stuff, and then it was science fiction. I came by it fairly naturally.

Did you notice the issues with representation early on or was that something that came to you as you got older?

The, the awareness came to me as I got older. When I was younger, I gravitated to … well, I mean, I’m still to this day an Iron Man fan. I loved reading Iron Man as a kid because I’m a technologist. I love technology. And so for me, it was like Iron Man was the epitome of technology. And when he’d come out with new armor, I was always like, ooh, what are the new gadgets in this arm? This one fires missiles! This one has a laser-guided something, something!” You know? And so that was always really exciting for me.

My family and my dad were very active in our Indigenous identity, but it wasn’t like the only thing we did, right? My dad was a college professor making sure that kids — Native kids specifically, but any kids — were getting into college and pursuing higher ed and learning, but there was always this aspect of well, let’s talk about Native history. Let’s not forget that. So that was, a part of my outlook, and then as I got older, I began to see that

I remember watching Predator early on, right, and Billy Sole, the character, played by Sonny Landham, the Native guy., it was like, oh my gosh, there’s a Native guy here. And I was so excited about that. And then he goes through the whole thing, and he’s the last one to die before Arnold takes on the Predator by himself. For me, gravitating towards that particular character, I wasn’t using that necessarily as a rallying character, but it was still important to see the representation was there.

As I got older I began to see it. I still think the character is probably one of the best representations in the 80s, but there’s still some problems, right? We’ve been working on an academic and more intellectual construct that I’ve coined “Critical Nerd Theory.” It looks at how we are looking at these representations in these spaces that we gravitated towards as marginalized communities and as marginalized people, especially in the United States, and what we gravitated towards and why we gravitated towards that — and the understanding that I can still love these characters and recognize that they are problematic in ways, especially now with a much more modern aesthetic.

It really developed when I started teaching. When I started teaching, it was just like, oh man, there’s just not enough literature for Natives. Why is this? Why are there no Native-authored, Native-centric comic books? Why are non-Native folks writing these stories about Native people and getting all of the accolades and yet some incredible Native writers I know that are family friends, people I know through the literary circles, are not getting the kind of same kind of recognition. That really began to lead me down the path of how we’re looking at critical media, how we’re looking at critical representation, and how all of that begins to intersect around popular culture.

How did you develop your thoughts on what you wanted to do about representation?

I have a performance background, and so I was doing performance poetry and slam poetry, and I was writing plays that were highlighting Native issues and Native folks in these spaces. I began to develop my own literary aesthetic with this. And then, I don’t know, it’s just kind of like we stumble into things, right? So there was just this seed, these critical moments where I was like, man, I’d like to write something else. I write poetry, and that’s great, but what can we do to influence beyond say the literary poetry sphere or the

That was really my entrepreneur side kicking into gear of saying, “Hey, there’s a gap in here.” My creative entrepreneurial side, my artistic entrepreneur, was being like, where can I find my own identity in this space? And recognizing that these means of Native comic books as a way of influencing a younger generation, my generation of comic book readers, from, what, 6 to 24, that really became, that was the impetus for developing and creating comics as a way of approaching that. And telling those stories in a way that would not be like an afterschool special, because you see a lot of that as well. Like “we’re going to tell you the history of Native people and look, American expansion is bad and Native people who are victimized.”

And I was like, listen, we can tell that, and we can show that in a way that is much more visually oriented so that we begin to undermine and reimagine Native identity in a way that hasn’t really been seen before, a way that’s not necessarily commercialized in the same way. I mean there’s still a commercial aspect because we’re selling books, but we try to create Native characters that we’re not talking about a Native person going to the powwow all the time. The comic books that I write are not just, well I’m off to do a ceremony or I’m off to the powwow today, and my life revolves around the powwow. That’s part of what we do, but there’s a lot of other stuff. It’s just day to day, you know. It’s just day to day living, and I wanted to be able to showcase more of that, and that’s why I think that fell into the comic book side because it is a visual medium and the visual medium allows a reader to begin to associate images with the text itself. And once we can do that, then we can to undo a lot. I mean it’s a long struggle, but we can undo the historical misrepresentation, stereotypical and tropey representations, of Native people by putting forward something more positive and more realistic.

Creating characters that people can latch onto, offering stories about full characters in interesting situations, is really the most effective way to push back stereotypes, and that seems to be pretty much your plan, and your advice for everyone else.

Just real stories, and then also providing the perspective from an Indigenous person myself in that way, but also a lot of my other colleagues. I mean, you can look at our predecessors. If you look at Black Panther — created by Jack Kirby, written by a non-black man, but doing some amazing work. Then it takes on a whole new dimension and dynamic about what you can talk about when you get Reggie Hudlin and Christopher Priest, and draw and write those characters. They added this whole new dimension to the character. Well, that’s what we seen on the screen. That’s Hudlin’s and Priest’s work in terms of talking about the African diaspora and talking about African nationalism versus Black nationalism.

Those are some of the incredible issues that I don’t think can be incorporated in the subtleties and the nuances by folks that are not a part of that community. When we even talk not only about the content but we talk about the creators of that content and how the creators are approaching the issues within that culture and the climate in which that culture exists, that’s when you begin to see some really dynamic storytelling emerge because it captures the subtleties and the nuances that go beyond simply the comic book tropes of “we’re going to punch the bad guy into the ground.” Black Panther taking on the KKK or the Black Panther taking on the white supremacist or whatever, that’s great. I’ve got no problems with Captain America punching Nazis, but the nuances within these characters, like these overt bad guys, is why I read comics. There’re particular morality plays that occur within a comic book structure and have much more significance when you have someone that understands the culture from which their writing because they’re not looking at, “what would be a cool image? Throw some feathers on him!”

Listen, my people don’t do that. I’m Pueblo. I think I have a very unique perspective of being a Pueblo writer in this world. I love my brothers and sisters from up north and my relations that are Plains Horse People. I was like, man, we didn’t do that. Pueblos are farmers. So how would I tell that story in a way that’s going to engage an audience and a comic book audience looking for a particular type of satisfying aesthetic and resolution where, yeah, I’m going to punch bad guys, but I don’t have to throw in feathers. I don’t have to throw in the tropes that have been prevalent within Native identity in pop culture for 400 years.

When I think back to being a comics-reading fan in the 1970s, my memories of seeing Native American characters other than those in westerns usually featured characters with these cliched affectations to highlight them as the token Indian character. Like Little Sure Shot in Sgt. Rock, with a feather on his helmet. I suppose it was well-intentioned, but at the same time, it relied on the tropes you’re talking about.

Which is why I go back to when I mentioned Predator, I mentioned that for a very specific reason. If you look at that character, he doesn’t have feathers. There are no feathers to that character. He doesn’t have one painted on the side of his helmet. He’s got long hair, but he’s really just another badass in the company. And he’s also the first guy to recognize the danger. “These things came down, and they were hunting my people because we were the greatest warriors a thousand years ago in our traditional stories. And we’re all gonna die.” Right? He’s definitely the nihilist of the group. I can expound on that in so many theoretical frameworks. But that was why I think it was so compelling and why that character has held on.

And again, I know that there are some other tropes that engage with that particular character, but the fact that he didn’t have a feather representation, he was just a Native

Pueblo folks, we’re the only people that kicked out the colonizer, but we’re recognized as being farmers and apartment builders. The Pueblo rebellion was the only time Native folks actually removed the colonial force and sent them packing. So how come Pueblo folks aren’t recognized? We weren’t because we don’t wear feathers, so we don’t fit that trope. I always make jokes about it, like mostly we farm and we’re were round and brown. That’s my joke that I make with folks. That’s what we do. But, man, we were pretty , and we were sophisticated long before there were settlers and colonization came to our shores and our people.

One of the stumbling blocks for white creators who aren’t educated on the subject has been to think of Native American culture as monolithic rather than varied and with numerous different histories and cultures. That’s reflected in their work, unfortunately.

And the imagery that we create for ourselves, etc., etc. And I think that has been the challenge. So when we’ve written and published and worked with other folks, there still needs to be an access point. There needs to be some sort of context for people to understand what’s going on. And the challenge and the battle is that we don’t have an easy path for that. It’s much easier to get onto a bestseller list when you write about Native people doing Native things, right? And looking like Native folks. And I say that in a way

From my perspective, we also have to include in the conversation Native modern identity, Native 21st-century identity and what that entails, where there’s a balance of culture and tradition as well as an iPhone and an electric car, right? I don’t ride around Albuquerque on a horse. I ride around Albuquerque in my car, I have a cell phone, and yet I still also understand, recognize, and represent my Pueblo communities. And recognize that there is a space for ceremony and there’s a space for traditional stories and traditional ways of being.

So that’s the hardest balance. That is hard for pop culture, a mass media audience, that has been accustomed and trained to seeing Native people represented in one monolithic way, for me to go in and wear traditional pueblo dress and have kids in Austin, Texas where I’m teaching them, being like, “that’s not really Native. Folks over there are dressed in Powwow Regalia, that’s Native.” And I was like, nope, this is Native too, and if you come to New Mexico, this is what we would be wearing. So it gives me a chance to educate. But I think with comic books, it also gives me a chance to educate in a fun way. That’s why I’ve gravitated towards that for the work that I’ve chosen as my career.

A lot of Native American culture as it’s presented in entertainment revolves around reservation culture. That’s obviously valid and should be addressed, but are there other aspects of modern Native life that are less covered in favor of reservation stories?

That’s a challenge within Native communities, right? Like getting folks to understand that 75 to 80% of the Native population lives in urban areas. That’s some of the stuff that we look at as Native entrepreneurs, scholars, influencers, etc., is recognizing that many of us live in cities and yes, we have connections to — well, some of us, not everybody, has connections back to our traditional homelands.

But that’s also a myriad concept as well, so that becomes an interesting dynamic of, across

The notion of the West is so hardwired, the romanticizing of Indigenous and Native existence is so high hardwired into the American collective consciousness. And I spend a lot of my time when I do speaking gigs, and when I present on this stuff talking about how all of these things have developed.

But here are the realities of Native existence and identity. It’s like saying that all of America is New York City or all of America is only represented by Kansas. Well, we know that’s not true. America is not represented by Kansas. There are so many facets to the United States and the people that live in the United States. The same holds for Native communities. That’s how I usually try to appeal to folks. Is America only Kansas or only New York? How is it any different for Native identity? It’s not only the Rez. It’s the Rez, it’s the history. It’s urban, it’s suburban, it’s university, it’s rural. It’s New York City, it’s Upstate New York.

And while you can have Native creators doing work that springs from all these concepts, it only does so much good unless the work gets out there and people actually see it. You’re covering all the parts of that process with your publishing company, your store, your convention, but those obviously exist because effective mechanisms aren’t commonly in place elsewhere to make the process happen on a regular basis.

There are a lot of Native creatives that are doing incredible work, and you don’t see it. I live in Albuquerque, but somebody’s doing work in northern Virginia right outside of DC, and they’re doing some amazing stuff, and they’re Native, and they’re talking about their own communities and peoples out there and Virginia and whatnot. But it’s a big old country. And if they don’t have distribution for that, then you know what happens.

And often with the big distribution companies and the publishing houses, they’re also accustomed to reading an audience in a way that you have to conform to various values and concepts around Native identity. I’ve heard from a number of my friends that are writers, not even comic book writers, but literary Writers, book writers who would get responses back from their editors like, ” see you’re going, but I can’t quite tell their Native can, can you add more cultural elements so that we can identify them.” You get these kinds of comments back from editors because that’s what the publisher is looking for

I think that’s starting to change, thankfully, but it’s present. And so when we’ve come at it from the company we try and say, “okay ” and we’ve been building that over the last couple of years with the shop. We need not only the content, we need a lot of content, and we need a lot of that content to be able to get into the marketplace through all of the means that we can.

And as you said, that perpetuates community which inspires people to create work, which makes more work available.

And then you have that math once everybody starts coming along with it. You can showcase to the big publishers that there is buying power, aka Black Panther, aka Creed and all these others, like, Medea. Like once you showcase that there are resources around it, then the industry is more than is more willing to provide the platform and the resources to be able to perpetuate that. And that’s what we’re aiming for. And not only us as a publishing company, but also for the creators.

I’m not looking at a monopoly. I’m looking at a space where Native creators can flex and build their portfolios and showcase that they can do incredible stories and provide a solid block of folks that when Marvel or DC or Disney or ABC — I guess it’s all one company now — when any of these bigger companies are saying, “we can tell the traditional Native stories but we have to have non-Native showrunners on this,” I’m like, “No, no, no, you don’t. We have so many Native showrunners, so many Native creatives that can step into those roles, that know how to do all of this work. You’re overlooking them.”

And that is when we really start. We can showcase, we can pull the blanket off of the structural prejudice, and that’s what we’re trying to do.