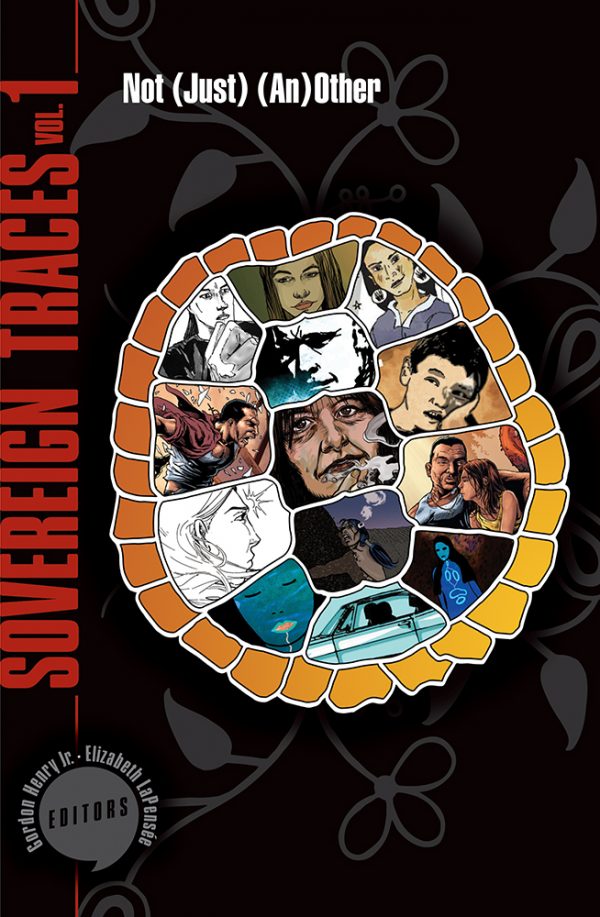

This recent anthology from Michigan State University, Sovereign Traces Vol. 1, edited by Gordon Henry Jr. and Elizabeth PaPensee, presents work from a number of Native American cartoonists paired with Native American writers to bring their work into sequential form. As the title to the collection hints, so many of the stories have to do with the idea of sovereignty as only remaining in the form of specters that the cultures have been able to pass through generations, though struggle to keep in a tangible form as multiple factors cause personal devastation.

“Werewolves on the Moon,” written by Stephen Graham Jones and drawn by Delicia Williams, depicts a parent-teacher meeting over a disciplinary action of a young boy. The boy has, in response to an assignment to draw what he predicts his job in the future will be, drawn a picture of astronauts on the moon and then a werewolf attacking them. In the dialogue between teacher and parent, it becomes obvious that the boys’ indiscretion is partly judgmental — he has no father — and partly cultural, but it’s also that he dares to not only answer the question non-realistically but emotionally. In a situation where Native Americans don’t finish school or end up as the janitor in the school, this boy is penalized for not fitting in with the program, not giving a canned answer to the question.

“The Prisoner of Haiku” could almost be a continuation of that boy’s story. Written by Gordon Henry Jr. and drawn by Neal Shannacappo, this story is more a poem about the nexus between art and protest and violence, and about silencing marginalized people. Following a man through his troubled life, this story once again addresses the idea of the forced suppression of self and the idea of cultural identity as unacceptable. When one form of the ability to communicate ideas is stolen, another forms with a vengeance.

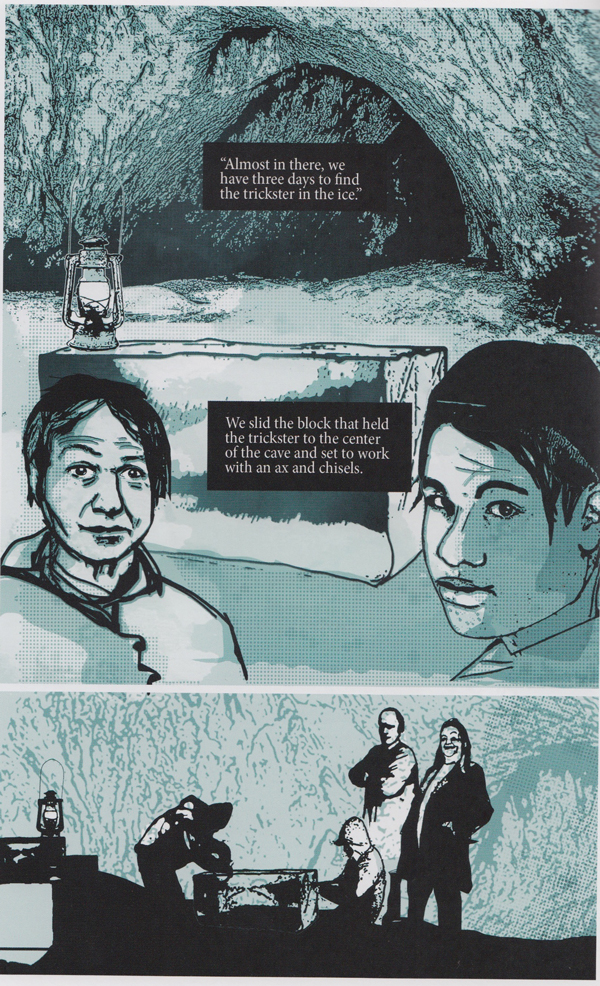

“Ice Tricksters” examines the concept of the Trickster in Native American lore and how it may be the personification of how things just never turn out perfect. Three guys take to a secret ice cave to create a trickster ice sculpture but have consistent burps to their intent and processes. It’s a soulful story of how mythology and life intersect in subtle ways, with GMB Chomichuk’s elegant and mysterious art adding dimensions to Gerald Vizenor’s friendly words.

“An Athabasca Story” indulges in some spiritual time travel, in which Elder Brother’s wandering through the wilds into unknown territory serves as a narrative for the past stepping into the present. When Elder Brother blunders upon an industrial site digging up tar sands and producing fuel with it. Land containing tar sand in Canada is controversial, with industrial efforts encroaching on First Nations land. A volatile encounter with a worker leads Elder Brother to attempt to steal tar sand for himself, but this being a fable, his attempt backfires and the story, written by Warren Cariou and drawn by Nicholas Burns, becomes fantastical, metaphorical, and chilling.

The idea of the Trickster is revisited in “Trickster Reflections,” in which writer Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair examines the notion of what causing chaos means in real life, with the idea of the Trickster as another part of self. GMB Chomichuk’s art adds further depth to the intense piece, giving it a darker psychological aspect while well-incorporating the mythological qualities. At center here is the idea of mythology as self-examination.

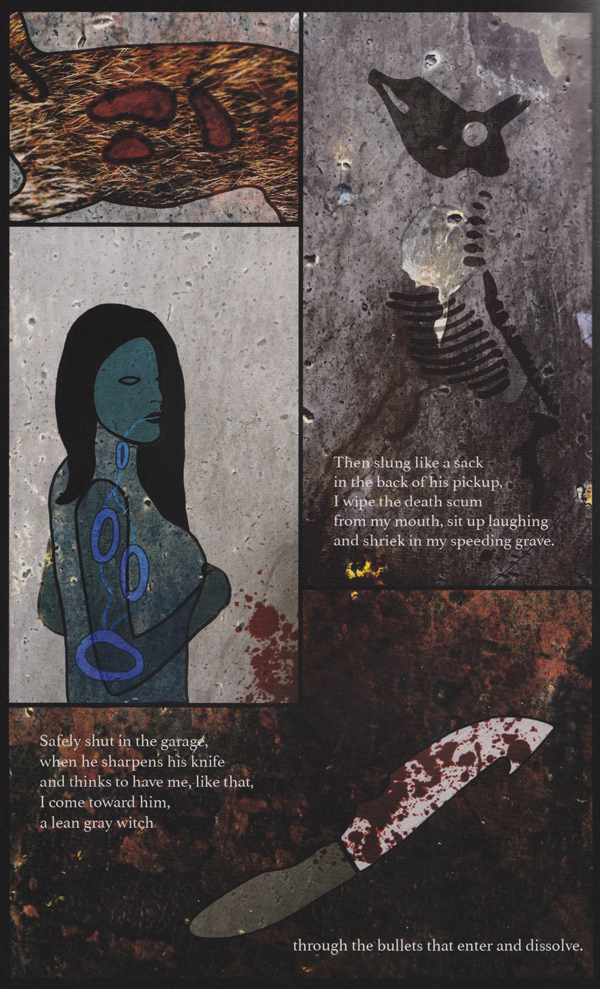

“The Strange People” adapts Louise Erdrich‘s poem into a mysterious piece juxtaposing the idea of antelope being chased by young men with the monologue of a woman contemplating a man she is involved with. The initial quote in the story is from a medicine woman depicting antelope as alluring creatures who compel young men to chase them, eliciting the concept of possession without understanding. They know they want it, but they don’t know precisely what it is. As the poetry bears witness, they cannot see it. The visuals are beautifully rendered by Elizabeth La Pensee in the form of cave drawings.

“Deer Dancer” recounts an incident at the Deer Lodge bar, wrapping the arrival of a woman around the inherent lost quality of a nation of people drowning their sorrows, or their disappointments or maybe just the fate of everything, while the woman prepares for a moment of honest display. Writer Joy Harjo evokes a deer alongside the rejection of white laws, while artist Weshoyot Alvitre renders the beautiful agony, the sublime defeat, that looms in the atmosphere of the barroom.

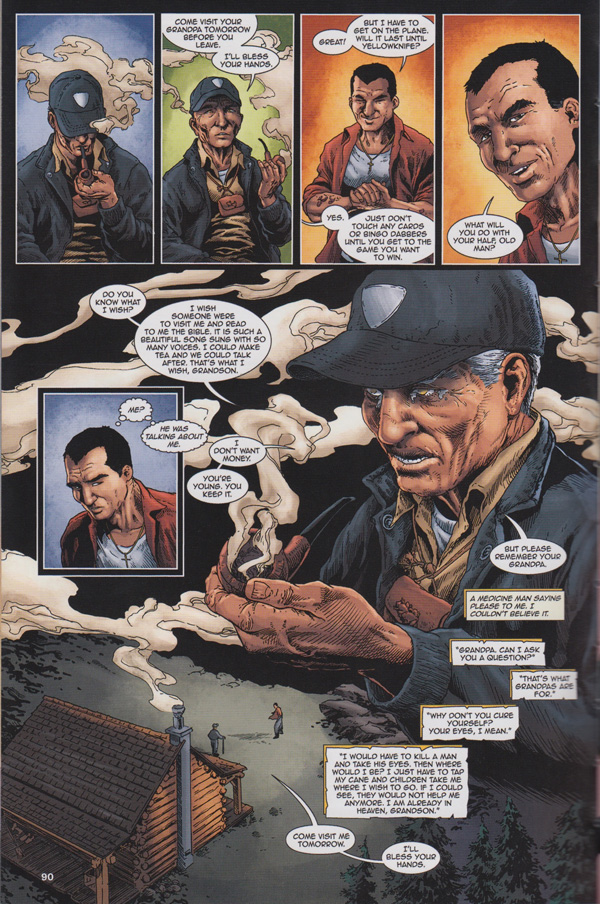

Richard Van Camp’s “Mermaids” is an intense noir-tinged tale of misfortune, as Torchy is found injured by young Stephanie and brought home. Tending to him, Torchy tells a story of God’s dislike of anything more beautiful than him, his violent reaction, and then we enter into Torchy’s nightmare, an unfolding of the story which brought him to the street where Stephanie found him. Once again, the personal story of a Native American, as drawn by Scott B. Henderson, is packed with people dying and disappearing, and the main character doomed to walk like a ghost through his own history.

Gwen Neil Westerman’s “Just Another Naming Ceremony” is the most upbeat story in the book, though it addresses something not so cheery. At a book signing, Native Americans who have some relationship with success meet and joke about their interaction with white culture on that level, the anglicization of names versus optimizing their nativeness as a brand. It’s a sarcastic and frankly cathartic conclusion, given some immediacy through Tara Ogaick’s personable cartooning.

This is an intense and exciting collection and, most wonderfully, uncompromising in its subject matter. It doesn’t push away non-Native readers, but it does demand respect for what it presents. This is both strong storytelling and strong advocacy, easily some of the most passionate storytelling I’ve had the pleasure of encountering in recent comics. These voices, both writers and artists, should not be on the margins of the industry published by a university press — thought that’s certainly wonderful and thank goodness for this project from Michigan State— they should be front and center, not only because of their message but the power with which they are expressed. I’m looking forward to the second volume, which will be released later this year.

Comments are closed.