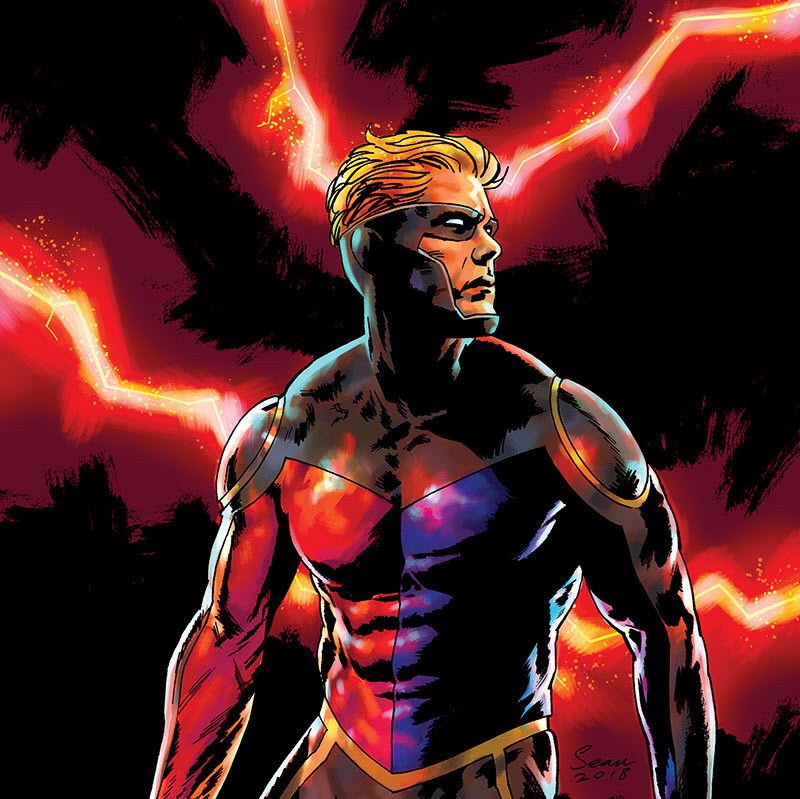

Created by Peter Morisi and first published by Charlton Comics in 1966, Peter Cannon is a character that lives under the shadow of his interpretation by others. Beyond Watchmen, the character’s comics presence has been mostly limited to reboots, modernizations, and the occasional guest appearance in a big crossover event.

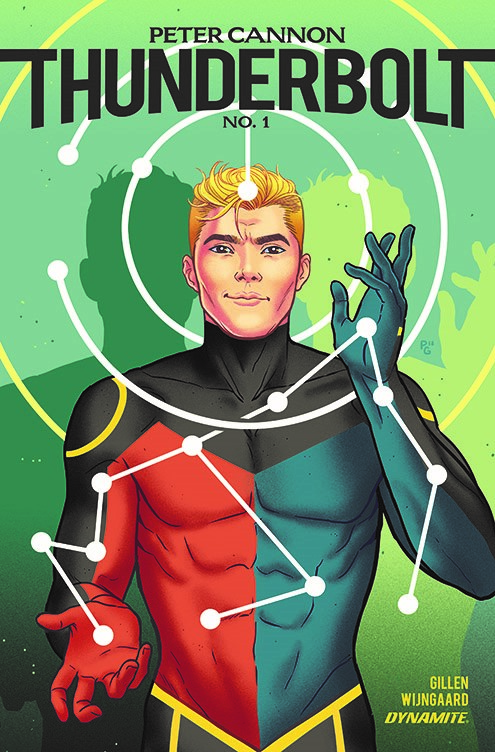

Dynamite Comics is now going for another run at the character (after their 2012 series by Steve Darnall, Alex Ross, and Jonathan Lau), to challenge his history and position him to become a powerful and even subversive voice in a crowded superhero genre that often collapses under the weight of its own clichés.

The creator whose responsibility it is to shape that voice for the upcoming Peter Cannon series is Kieron Gillen, a writer with a lot to say about superheroes, the things that they can become, and the alternatives characters like Cannon can offer despite deceptively narrow publication histories.

Recently, the Beat had a chance to talk to Gillen about his approach to writing Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt for Dynamite Comics and what we can expect from his interpretation of the character.

Ricardo Serrano: One of the things that is really impressive about your work is that it reads and feels very well researched. When you read a Kieron Gillen comic you get the sensation of being exposed to a story in as many dimensions as possible, supported by the weight of its research. Coming into Peter Cannon and the history that he brings, which sometimes plays against him, did you feel like you had to address his publication bio and the things he’s influenced or did you just want to have a fresh start with him?

Kieron Gillen: When I said yes to the project, I just wanted to write a superhero comic again. I hadn’t done a superhero comic since I left Marvel and I left superhero comics because I felt I was burnt out on them. Or I felt like I was about to be burnt out and worried the work might suffer. The moment I realized it was when I was doing Star Wars and I was enjoying the Star Wars stuff so much more. Description was coming easy and free, so I thought ‘oh no, I really am close to burn out and I need to get out.’ Over the last year I’ve been getting that twitchy feeling, so I gave a shout to Nick Barrucci at Dynamite and spoke about wanting to get back to superhero writing, or at least something that scratches like a state of the art address, I guess. The idea is certainly self-aggrandizing, but the idea is lets make a really fun superhero comic, in the same way that me and Jamie McKelvie were doing with Young Avengers, like lets do a swing at something.

Peter Cannon is a swing. Not the same of sort of swing, like a cross between Uncanny X-Men and my Young Avengers, where it has kind of like of like the same scope of Uncanny X-Men in terms of scale and the attitude of Young Avengers. That’s kind of the idea. One half of it is actually the superhero comics side of it and the other is ‘what can I do with a superhero comic?’ The other part of the research is, as you said, your Peter Cannon. The thing with Peter Cannon is it has a long history but no a wide history. The actual cannon is really, well—you kinda make the pun by accident—Cannon’s canon is quite small. There’s the original Cannon by Pete Morisi, some eleven issues, I think. It’s very small. And then you’ve got the Mike Collins early-90s version which is another 12 issues, followed by the Dynamite issues which builds mainly on the first run by Morisi, or at least riffs around it. And that’s basically the canon. So I got all of that and I read all of that. I picked it apart and thought about it. You know, what makes that guy interesting.

Part of writing a superhero created by another person is looking at what works and why would anyone care about this person. What makes him interesting are these weird bits and pieces. Like one the weirdest things, and the first Dynamite run is strongly based upon this, is this weird bit where we have this ‘believe in all the potential of humanity’ type of guy and he creates a dragon. And you’re like, you did what, Peter? That makes Dynamite’s first run so interesting. So I synthesized all of that.

And then there’s the elephant in the room, being that he’s this character with quite a small cannon who is the inspiration for probably the most influential supervillain in the last 30 years. Well, antagonist is probably nearer the point, but he’s the inspiration for Ozymandias. And if you ask 99 out of 100 superhero comic fans to tell you something about Peter Cannon, they’ll say inspiration for Ozymandias. You can’t avoid that. As a device to talk about influence and how comics change, with Peter Cannon you cannot avoid the ghost of Ozymandias. But it has to be bigger than that.

Serrano: Thinking about Mike Collins’ 1992 run, which tried to make Cannon part of the DC universe and features Green Lantern with mentions of becoming part of the Justice League, why do you think Cannon never became part of the larger universe?

Gillen: It’s always hard to say. When a run fails, out of all of the reasons that can explain it, the main one is usually just bad luck. It’s really hard to insert new characters into the DC Universe anyway. I mean, here’s a peak human character and he’ll be sharing space with Batman. So he can’t be that peak human because we already got this other peak human hanging around. It’s one of my standard rants about these two big universes. It’s kind of like my baby boomer rant in the sense that you have these people in these positions and they’re never going to retire and so you can bring a character into the universe that is paragon of all that’s good, but that job’s taken. That’s Superman. So when you look at adding people into those universes you’re kinda looking into spaces that aren’t filled yet. So it’s difficult in the sense that it’s a job, you know what I mean?

When me and Jaimie were reinventing Ms. America we were going for a street-level Wonder Woman. That was basically what we wanted. And that’s a very Marvel thing to do, street-level heroes. I mean, people with street-level attitudes have a weird power cap, which always felt to me like a glass-ceiling thing where if you have a certain kind of accent you don’t get to be the Silver Surfer.

The way it happens with Mike Collins’ Cannon is Peter gets beaten up and put in a coma for a year. This makes him think he’s not Justice League material and that makes him find his own level and kind of explore that. I’ve never spoken to Mike about this, but I guess it was a way to make him quite likeable. But the thing about Peter Cannon in the original book is he’s not likeable at all. And that’s what I’m digging into. The big motif in the original comics is ‘Oh no, someone’s in trouble’ and then Peter Cannon goes ‘Not interested.’ And then someone’s like ‘go on, Peter’ and he goes ‘okay, I’ll do it.’ That’s where his friend Tabu [Cannon’s crimefighting companion] comes in and says I need you to be Thunderbolt. That dichotomy is interesting. He’s like a more responsible early Peter Parker. Actually, he’s like if Peter Parker had better ethics and morals. And with Tabu it’s like Uncle Ben never died.

Gillen: Well, it’s likely that most people who pick up this comic won’t know who Peter Cannon is, so I wanted to make it a clean start. When you pick up this book you get a state of the art event-level superhero comic. We’ve invented a whole universe and other characters around him, so we’ve kind of gone for it. But if you know Peter Cannon you’ll be able to see that we’ve sort of synthesized the three previous runs and go ‘let’s take him and add some fifteen to twenty years to him, take him to his early forties, and show he’s somewhat retreated a bit.’ It’s kind of like a Dark Knight Returns start in that he doesn’t really want to be involved.

It’s to some degree close to the trope of the white savior–White guy with powers given by isolated settlement in the East, but rather than someone like, say, Iron Fist, the interesting thing is Peter Cannon literally has not earned it. He’s not the best or anything else. He didn’t choose his path. He knows he’s not worthy. He’s an apex human, but he’s an apex human because of this other civilization that is better than we are.

You can see it in the preview, where Peter basically says all your civilizations are corrupt, why should I look after your civilization if you don’t even look after your poor. To write him into a personality that sees him judging the world and its morals so strongly brings about the question of whether to lock him in those conventions, where he goes ‘yeah the world stinks.’ That’s why Collins’ run is so important. He makes him into a likeable guy. And Tabu as the companion in the book is very important because he humanizes Peter.

The idea of the mean genius, the idea that being mean and being smart are the same thing is a trope I don’t have a lot of time for. So Peter Cannon starts there but we take him other places.

Serrano: Regarding Tabu, in the previous runs we’ve seen him serve as a sort of moral compass for Thunderbolt. He’s the character that keeps Peter on the path, always reminding him that the Thunderbolt title could’ve been his as well. Also, he’s not just another non-white sidekick that lives vicariously through the hero. I can only speak to the later runs, not the original one. How do you see Tabu in the comics that came before and how are you approaching him?

Gillen: I don’t want to talk about Tabu that much yet. As I said earlier, he’s the one that humanizes Cannon in the previous books. That they stay friends doesn’t say much about Peter. Definitely says a lot about Tabu. Sometimes I feel Tabu is treated quite harshly in the original comic. Too much like the butt of a joke. But you’re right, he’s the moral core of the book. He’s a living Uncle Ben that basically always pushes Spider-Man to do bad things. This sounds like I’m going to kill Tabu. I’ll say this up front, I’m not.

The idea that you learn with living with somebody is interesting. The fact that they are a little bit older adds to this. They’ve been friends for a long time. Their own personal history and how they’ve succeeded and how they’ve failed each other is really quite important emotionally. Tabu dances quite gracefully around at the idea he’s Peter’s servant. He makes it clear that Peter is his friend and that he is not his servant. What that power dynamic ends up being is explored in the book.

Serrano: The Peter Cannon character, in his various versions, has always reflected upon the times in which he was published. Collins’ run saw him commenting and interacting with post-Cold War politics. In Watchmen we see him become a reaction to a world held hostage by the threat of nuclear destruction. In Dynamite’s first Cannon series there is a continuation of the nuclear fear theme, with added focus on disarmament. Considering you’re bringing Peter into a very turbulent political environment that’s constant and everywhere at once, what do you want to say with your version of Peter Cannon?

This is an example of what I want to talk about with Peter Cannon, by the way. I speak to that kind of stuff returning. But I also speak about the manipulation of the media. I mean, The Wicked + The Divine is all about manipulation through stories. All of that is in there and it feeds into it. But it’s also my statement on superhero comics. It’s about what I love about the genre and what I hate about the genre.

I don’t think I’ve ever done a straight meta superhero comic, like Kingdom Come. Half of Grant Morrison’s stuff is about the superhero genre and what it does, where it goes right and where it goes wrong. It’s the closest I’ve ever done to that. This is me talking about what art is for and what this genre is for, what makes me laugh and what makes me fucking scream.

Serrano: Thanks for the chat!

Gillen: A pleasure.

Cool.

Comments are closed.