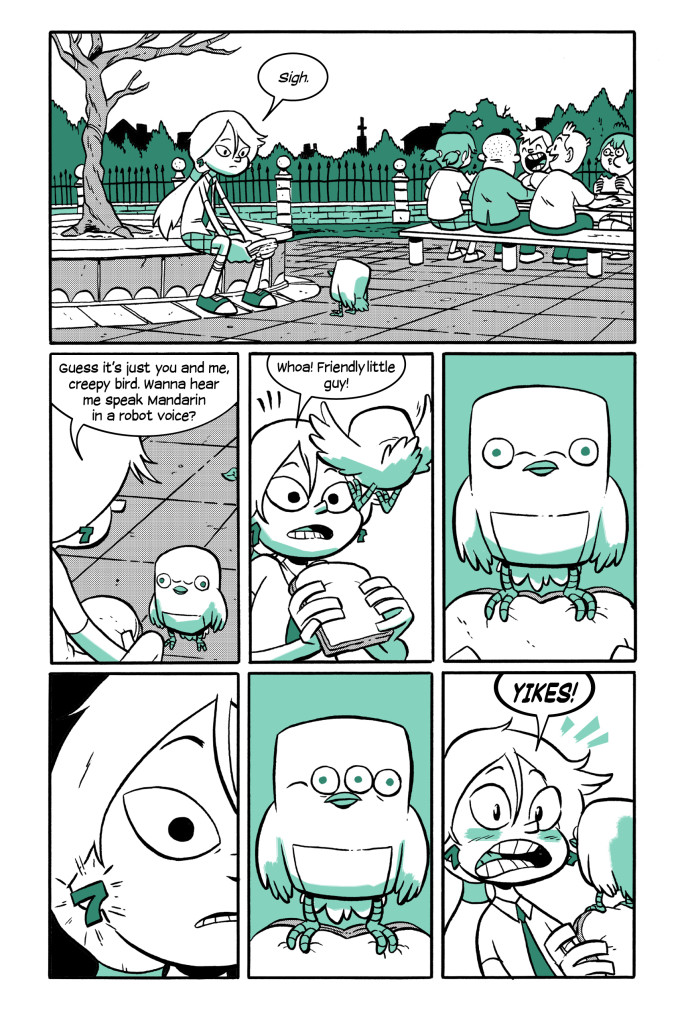

Gene Luen Yang, multiple Eisner winner and National Book Award finalist, has released his latest work for younger readers, a collaboration with Adventure Time artist Mike Holmes entitled Secret Coders. This exciting new volume from First Second, the home of Yang’s award-winning American Born Chinese, Boxers & Saints, and The Shadow Hero, centers on a young student named Hopper as she enters an academy full of puzzles and challenges to be solved– all of which are based around concepts related to computer programming. Teaming up with her new friend Eni, and a programmable robot turtle, this is a tale designed to delight and educate readers of all ages.

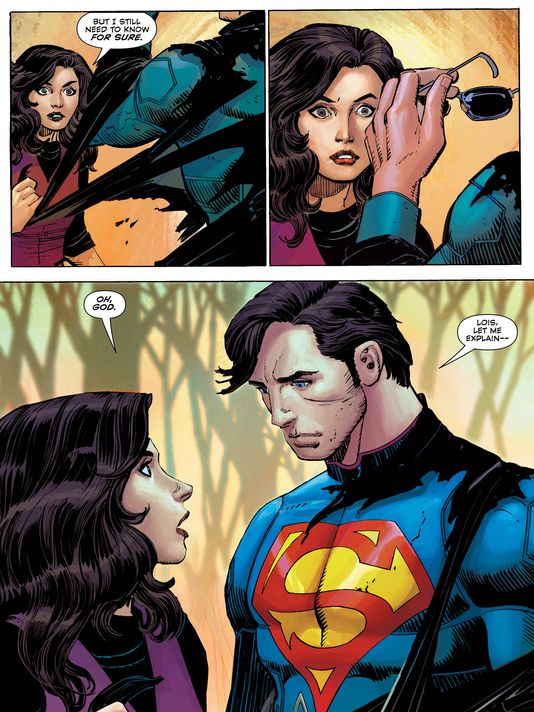

When Gene and I last spoke, we discussed The Shadow Hero just as it was being released in softcover. One year later, he’s won the Eisner for Best Writer for that tremendous work and his efforts on Avatar: The Last Airbender for Dark Horse. He also became the writer of the main Superman title at DC Comics. It’s always a delight to get to speak with Gene, and consider him a friend that I’m proud to support. He was kind enough to chat with me over the phone for nearly an hour a few weeks back. Here is an edited version of the conversation:

I read Secret Coders a few nights ago. I was telling a friend of mine about it today and she thought it was quite the inventive idea, a book about coding and introducing young readers to coding. She outright stated: ‘I’ve never heard of anything like that’, I think you’re probably about to enter a new niche in the marketplace.

Well, that’s kind of a dream of mine. I taught high school computer science for over 15 years, about 17 years, and I’ve always — And you know, being a comic book fan, I’ve always been interested in using comics to teach, so this was kind of me finally being able to do this. I’ve been thinking about it for a while.

Good. Yeah, you know that was actually going to be my very first question. I read the afterword where you talk about you took some coding classes in summer school. I think you said you were about 6th grade, 5th grade, something like that.

5th grade, yeah. It was between 5th and 6th grade was when I learned how to code.

Which are the worst years ever for a kid, at least they were for me.

Oh, really?

That transition between elementary school and middle school is awful, I thought.

Yeah, yeah. You know, when I was growing up– It’s different now. But when I was growing up, it was K-6, it wasn’t K-5. So I didn’t actually go to middle school until 7th grade. They called it junior high back then. So for me, I was at the same school and I have to tell you, when I was a kid, I loved summer school way more than regular school because during the summer you get to choose your own classes. Usually my mom would put me in these programs because I think she just didn’t want me at home watching TV, and that’s where — I started going — I really learned how to do comics during summer school. I took a comic book making class when I was like in 7th or 8th grade, and I learned how to code in 5th grade. These are the two big things in my life I learned from summer school.

I can’t believe summer school offered those kinds of things. Jeez, maybe I just went to terrible schools, but that’s pretty amazing that they had both comic book making classes and coding classes, especially — I think you and I are fairly similar in age. I’m not going to assume too much. I’m in my early to mid-30s now, so we’re probably close.

Oh, so you’re younger than me, yeah, I’m 42. You’re a little younger than me. You know, I think part of it was that I grew up in the Silicon Valley, so a lot of the parents — My mom was a programmer. My dad was an engineer. A lot of the parents of my classmates would work for like Apple or a lot of the other big tech companies around here, and they would be really interested in bringing in technology. I remember seeing like a– You know one of those Wacom tablets? It wasn’t Wacom. It was this other company called Koala that did that, and I remember being in elementary school and one of the dads of one of my classmates had worked on it, so he brought it in and showed it to us. It was pretty cool.

Sadly, the only computers I ever saw when I was in school were the old green and black Apple IIs, and I think you talked about that a little bit, too.

Yeah. Yeah, that’s exactly– That was my first computer. I loved those computers. Although, dude, you’re probably almost a decade younger than me, so I’m kind of surprised that they still had those around when you were going through school.

Well, I grew up in a poor community in rural Georgia, so you can imagine the schools’ funding wasn’t the best. It wasn’t until I moved back to Virginia with my parents, that I was able to play on a computer that had something like Sim City on it. Before that, my computing life centered on Number Munchers at keyboarding class *laughter*. Focusing on those years for you specifically, you took coding in your elementary to middle school years, and it was obviously something you probably continued to work on up through college. If I remember right, weren’t you working as a programmer for a living at some point?

Yeah. I mean, I majored in computer science when I went to UC-Berkeley. I did the software version. That was a major [track], so I didn’t really do much hardware. I minored in creative writing. After I graduated, I worked as a programmer for two years and then I started teaching high school. I taught high school Computer Science. So I taught that for a long time, yeah, for about 17 years.

And then so at that point you transitioned over from teaching into a comics career with works like American Born Chinese and the like, right?

Yeah, I was doing some comics. Like I started doing comics right before I started teaching. I was just about a year or two out of college when I started. At that point it was like mid, late 90s. I think Marvel Comics had just declared bankruptcy. People were predicting that the entire direct market was going to collapse. You’d go to these comic book conventions and nobody would be there. There would be more exhibitors than there were attendees, so I got into comics at around that time and I remember just thinking that “I don’t even know if the industry will be around in another 10 years, so there’s no way I can make a living at this.” I always, from the beginning, thought of comics as this thing I would do on the side. It was, to me, the flip side of the coin to teaching. Teaching, you’re always around people, and then in comics you’re usually by yourself.

Yeah, I was. I would always be doodling. I went to college wanting to major in art. I grew up reading comics. I grew up drawing and cartooning, and when I was really young I really wanted to be an animator. So I was still thinking about that when I was in college. I graduated in ’95, so that was the year that Toy Story came out, and I remember it — I took a graphics class in college, and they talked about some of what was happening in the animation industry, so I thought about that. I thought about maybe going to get another degree. Like after I got my computer science degree, I was thinking about getting another degree in animation or something, but so I was always interested in art, I took classes at a local community college, but I never got a degree in it.

But you decided that you were going to continue being an illustrator for a while rather than just being a writer that had other people who would do that work.

Yeah, I mean, the corner of comics that I was attracted to was the American indie scene, where most people were writer-illustrators. Most people would do everything, and I really liked that. I think a lot of cartoonists are just control freaks. We like being in control of the whole project from beginning to end, so we want to do both the writing and the drawing. Now as I’ve gone, I think I’ve gotten out of that, but definitely in the beginning, that’s what I liked. I liked being in control of the whole thing beginning to end.

Well, certainly my favorite works are done by writer-artists, generally speaking, so I can understand why you would lean towards doing that. And you’ve created some great work in that vein. I mean, you and I talked about it last year, including my appreciation for stuff like Boxers & Saints and American Born Chinese. I can’t get enough of your actual illustrating, so I hope we get to see more of that soon.

Oh, well, thanks. Yeah, I am working on another project that I’m going to draw, but it’s definitely still in the early stages.

Let’s just flash forward now to today and the real matter at hand. What made you decide to pursue Secret Coders as your project that would follow on from The Shadow Hero. I know this is something that’s been in the works for a while, but when did that first kernel of an idea sort of spring to life?

I’ve been wanting to do this for a long time. Like I said, when I first started teaching, I remember I used to tell my students that I was a cartoonist, that I did comics. I’d tell them on the first day, because I thought it’d make me seem cool to them. And I very quickly learned that it did not. Especially when I started teaching in the late 90s. Nobody was reading comics. Nobody knew what a graphic novel was. So it definitely didn’t make me cool at all, and eventually I just said I have to keep these two worlds separate. I’m a cartoonist at night. I’m a teacher by day. They won’t cross paths.

But then I had this one experience in a math class. I was teaching an Algebra II class, and I was also serving as the school’s educational technologist at the time, which is just a fancy way of saying I would help other teachers use comics in their class — Use computers in the classroom, integrate technology into the classroom. So what that meant for this Algebra II class was every couple weeks I’d have to miss a couple days, a couple sessions, because I was in some other teacher’s classroom helping them out. To make up for that, I tried videotaping myself doing lectures and asking my sub to play those, and it didn’t work very well. My students hated the videotaped lectures. They just thought they were totally boring. And as a second try, I would illustrate these lectures as comics, and I’d do it really fast with just a sharpie on typing paper. Every lesson would come out to four to six pages. I’d xerox them and ask my sub to hand them out, and these turned out like — The kids really responded to them. I was really surprised, because I thought that like the modern generation, they like looking at screens. I thought they would have liked the videotaped lectures better, but they definitely responded better to comics, and that really got me thinking.

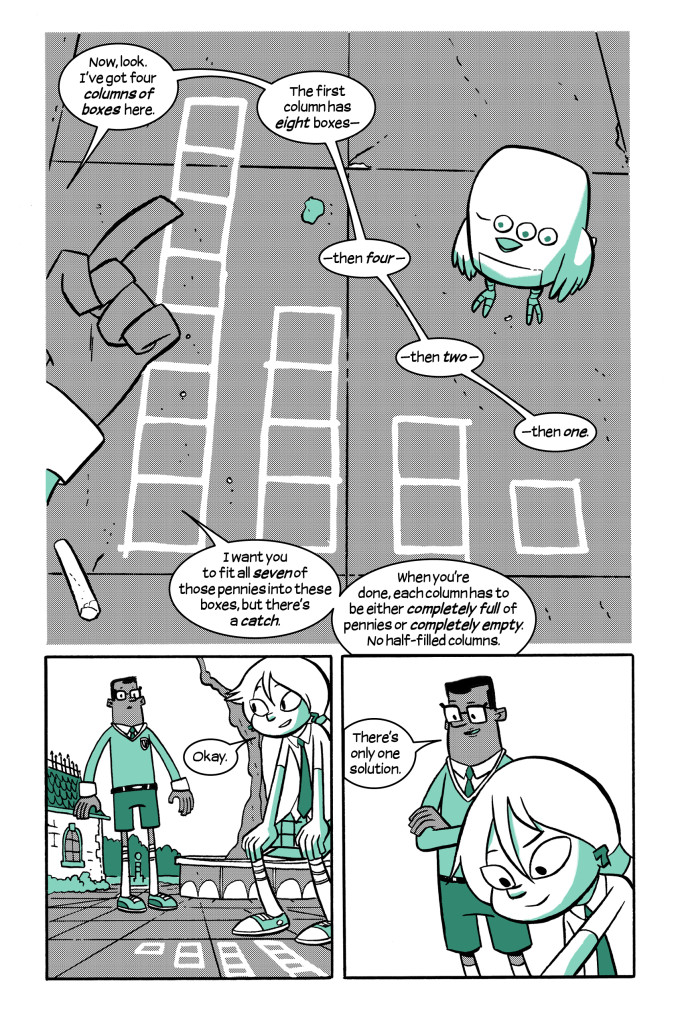

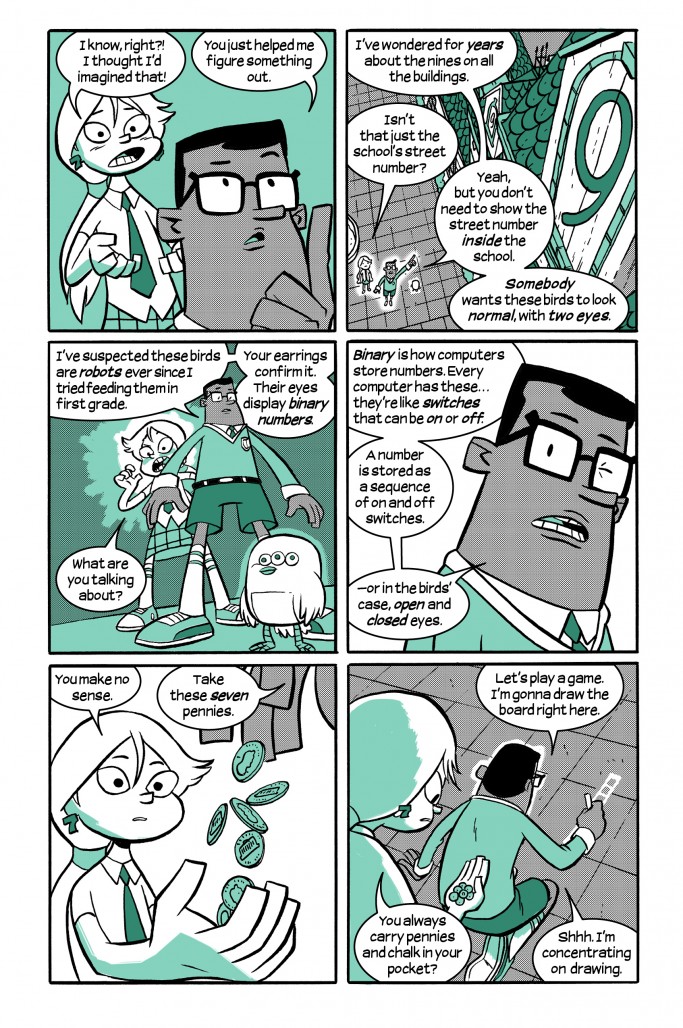

I ended up getting a master’s in education. I did my final project on using comics in the classroom, and it was based on that experience. It was based on this idea that there were just certain kinds of information that are better conveyed through sequential images, sequential still images. The fact that the images are still allows a reader to really think through them, and the fact that there are images allows them to think visually. So I think there are certain concepts in math and in computer science where that becomes a really key aspect. So all the way through when I was teaching coding, I taught two levels of coding. I taught an introductory one, and I also taught AP, the advanced placement version. In both of those classes I would use a lot of — Like when I was up on the blackboard, I would teach them this visual way, really visual way. I’d end up drawing a lot of charts and these sorts of things, and I just always thought like if I wanted to convert this into a book, it couldn’t be a prose book just because so much of my lecture was visual. It would have to be something like a comic book. So that was the kernel. It was me being in class teaching and noticing that I was using lots of visuals in order to convey these concepts, and how would I get this into a book.

And how long ago was that?

I mean, I started teaching high school computer science in ’98, so I don’t even remember. I got my master’s degree in education in ’03, so that’s when I did that math project, and just somewhere along the way — I mean, it’s just always been on the back of my mind. I think I’ve been really attracted to the intersection between entertainment and education for a really long time. I grew up a Disney fan and those were the parts of the Disney empire that most interested me in that kind of stuff, like Epcot Center, you know what that is in Florida?

All too well. Tomorrowland, what the people of the 1950’s thought the future would look like, to quote The Simpsons.

*laughter* That whole thing is just an educational theme park, right? It’s right in the intersection between education and entertainment, and that’s why I didn’t want to do Secret Coders as straight lessons. I didn’t want to just be purely educational. I wanted to see if I could weave a narrative and use educational goals together.

That was going to be my next question. I find in my experience that it’s very difficult to form a narrative around something that’s so analytical. It’s almost as though you’re crossing like the left brain and the right brain in a way that almost doesn’t seem to compute easily. I’m curious how one approaches forming a narrative that’s engaging around mathematics and computer science, which for me, as someone who knows nothing about that, it just seems like such an insurmountable and tough task, which to no surprise you accomplish wonderfully here.

Oh, well, thank you. I mean, I’ve got to say, I’m really nervous about this book, because I just don’t know — it’s exactly that. I worry that the educational part will get in the way of the entertainment and vice versa. So I try to follow a very specific structure for each of my chapters. I try to make sure that there’s some kind of a lesson that’s built in, so the main characters will go through some kind of a new concept, and then at the end of the chapter, I throw almost like an exercise out to the reader, like a little puzzle, and that’s kind of how I structure my lectures, too. For example, in my computer science class, I’ll present some kind of a new concept, and then at the end I’ll end with some kind of a puzzle or problem for my students to solve. But, it’s a challenge. I feel like I need to have the book come out and interact with multiple readers, especially readers in the target demographic to find out if I did it right. I think it’s just — I think it’s hard. It was hard for me to figure that out. I look at a lot of the cartoons that they have on PBS, like they have this one called Cyberchase, which is all about mathematical concepts, and they have a bunch of other ones, where it’s not just for entertainment. It’s also for education. Even Dora the Explorer is like that, but I do think a lot of times the temptation is to make your characters in those sorts of narratives simply avatars. As if they’re almost like cardboard cut outs, and they’re purely just there as stand ins for the viewer or the reader for the student, and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted my characters to feel a little bit more real than that, and I wanted them to have flaws and like desires, and that kind of thing.

Yeah. And I think that’s reflected in the work, and that kind of perfectly segue ways to my next line of questioning. So do you see, considering both Hopper and — Is it Eni (EE-Nigh)? Did I pronounce that right?

P: Eni, it’s Eni (In-ne).

Eni, okay — You can definitely hear the hick in me. So they’re about the same age you were when you started to take coding classes and that dreaded summer school session that you talk about. Do you see much of your own personality or the personality of your children or the children that you’ve taught in these two characters? And not to double up on the question, but the challenge of formulating the voice of someone who is entering that pre-adolescent stage, how does one tackle that?

Definitely, I mean, I feel like for every author there’s a piece of yourself that goes into every single character that you construct, even the antagonists. There’s a piece of yourself that goes in, and that’s definitely true for Hopper and Eni. Both of them are actually inspired by real people. I kind of amalgamated. Programming started off as a “woman’s job”, as seen as something that only women did, and that’s because — it’s not for good reasons — it’s because back in the early days of computers, they thought hardware was the really important stuff, so men only worked on hardware, and then software was almost superfluous, so women got to do that. Even the very concept of programming was created by a woman. It was a woman named Ada Lovelace in like the, I don’t know, 1700s or 1800s, a long time ago. There was also a really prominent woman in computer science named Grace Hopper, and she was kind of a rebel. She got divorced when divorce when it was really, really frowned upon. She fought for this idea of a compiler, which in computer science is a program that translates code that a human can read easily into code that a human can’t read easily, that’s meant for a computer. That was a revolutionary concept, and a lot of people fought against it, but she pushed it through. My character, Hopper, is named after her, and I wanted her to kind of have that sort of rebel element to her personality. The other character, Eni, is inspired by two people. One is an NBA superstar named Chris Bosh. Do you follow the NBA at all?

No, actually. I’m really just a baseball guy.

Okay. Okay. There’s this NBA superstar. He’s on the Miami Heat. He’s got two championship rings. His name is Chris Bosh. He was like LeBron James’ right hand man when LeBron James was in Miami, and even though Chris Bosh is this elite player, he actually gets a ton of hate. Like if you look on Twitter and you just do a search for Chris Bosh, the vast majority of the tweets about him are making fun of him, which is really unusual for an athlete of his stature. And I always wondered like why that was. And you can kind of see it. Like when you watch him play, there’s like a weird awkwardness to him, and I remember seeing him running down the court and thinking, I recognize that awkwardness. It turns out that he’s like this total math nerd. He was part of the math club in his high school and he was really into coding. He really loved computer science. He went into college wanting to do a computer imaging major, but then he got too good at basketball and ended up getting sucked into the NBA.

So Eni is kind of like that. I wanted Eni to be like Chris Bosh, really good at basketball, really good at coding, but unlike Chris Bosh, he’s going to choose coding over basketball. And actually even Chris Bosh now, like he takes his millions of NBA dollars and he invests it in these tech companies, because he loves it so much. I found him an intriguing person, so he’s inspired by him. Additionally, Eni’s personality is patterned after an African-American student that I had in AP computer science who was a really strong student, really strong programmer, but everything about him was muted. Like if you were to write out this students’ dialogue, he would never use exclamation points, so that’s what I wanted him to be like.

I should say I’m learning to be a basketball fan now. I have an 11 year old son. When I was growing up, I hated basketball. But I have an 11 year old son who is kind of into it, and I’ve kind of gotten into it with him.

There’s a piece in Secret Coders that really struck me. When we learn more about the relationship between Hopper and her absent father, their mutual love of basketball, and his description of how every player is basically a walking statistic, and that kind of struck me as an interesting way to look at that sport.

Yeah, that’s something that surprised me as I started reading basketball websites and basketball articles, is that there’s so many numbers that they throw out. They talk about a player’s percentage within these zones, and they talk about like percentages of different combinations of players.There’s a crazy amount of statistics. Nowadays when we think of professional basketball, we think of the NBA, but in the 70s there were actually these two leagues. There was the ABA, the American Basketball Association, and the NBA. The ABA was kind of like the underdog. And the way they competed actually was by throwing out more statistics. Like they would publish way more statistics about their players than the NBA would, and that’s kind of how they tried to drum up interest. Now a lot of those statistics that the ABA came up with the NBA has incorporated.

You’re like a walking history book on this subject!

Well, the other project that I’m working on is basketball related, which is why I’ve been reading up on basketball. But as a math nerd, as somebody who hated sports when I was little, I was kind of shocked to find like all these math nerds who are in the world of basketball. Like they do these crazy calculations and algorithms to figure out who to pick when the draft comes along.

Oh, wow!

It’s like a math dependent decision, yeah.

I mean, when I was in school, basketball was a thing I tried to avoid in PE…

Yeah, me too, me too. I was totally like that.

Then again, my dislike of math and that still go hand in hand. Anyway, about the scripting and the timeline at the creation of the book, when did you complete your first sort of path through the script before you handed it off to Mike (Holmes)?

Oh, it’s been a while, maybe a year or two ago was the first complete draft. So I wrote the book in thumbnails, and I pass off the thumbnails to Mike, and then Mike does the gorgeous finished artwork.

Did you and Mike have an established relationship before you were partnered up for this series, or were you an admirer of his? How did this partnership come about?

No, no, I never met him when we started off, which is actually unusual, because for all my other collaborations, I knew the person before we started working together, like we were buddies before we started. But with Mike, we were introduced by our agent, by Judy Hampton, and she thought we’d be a good fit, and it turned out we are. I mean, he has the Saturday morning feel to his work that I really wanted.

No, I can see it. And I assume your working relationship was a good one then. I mean, there was never — It seems like Mike was probably right on board with your first draft. Did you ever have any — ever have to go back and sort of redo anything or was it all pretty much a straight-shot from thumbnail to finished product?

Yeah. I mean, there’s been — It’s been really good. He’s like really fast. He’s one of the fastest cartoonists I know, crazy fast. And I think every now and then we tried to make some adjustments, but they’ve all been really tiny. I can’t think of any major issues that have come up. I mean, I think a lot of it is that like a lot of the smaller adjustments is that when something is wrong — like when something is drawn in a finished way you can see more clearly whether something isn’t being communicated well, especially when it comes to the coding stuff, right? So there’s some tweaks that we’ve had to do for that, but outside of that, it’s been really great.

There are a couple of things. One is that Mike is not a coder. He actually hasn’t had any experience drawing — I mean, programming at all. So through him we get like a fresh perspective. You know sometimes like if you’re too close to the subject you can’t really see when you’re not communicating clearly, so he’s kind of a check for me on that. And then second is that his drawing is just filled with this really fun energy. I think because of the subject matter that we’re dealing with, because coding can sometimes be stereotyped as dry, that having that energy is a really good balance.

One other thing that I noticed is the color scheme, which I mentioned a second ago. It’s green and white. I’m kind of curious, is the green color scheme an intentional sort of nod towards early computing.

Yes. Yes it is. I mean, we wanted a one color scheme book, because we want this book to kind of fit in. Like it’s almost like a genre of books right now, they’re all middle grade graphic novels, and they’re all one color, for example, there’s Baby Mouse and Lunchlady. Those are two of the more prominent titles, but there’s a whole slew of them, and they’re produced that way because it’s cheaper, because you can get them out faster, and they’re usually about the same length as Secret Coders is, just under 100 pages. We wanted this book to fit on that shelf. We were talking about what colors to choose for our one color, and it seemed like green would be a good way to go, exactly for the reason you said. It’d be like a nod to early computers.

No, we’re planning to keep it green, yeah. At least for the foreseeable future.

How many volumes are we looking at, by the way?

We signed for three. I’m hoping to do three more after that, and my agent is talking with First Second about volumes four, five, and six, but we’re definitely doing three.

With books two and three — I assume that the end of chapter quizzes/problems to be solved will probably increase in difficulty. Is that sort of the goal?

Yeah, yeah, that is sort of the goal. I think like the way I think of it is these books aren’t necessarily a replacement for a coding class. I’m hoping that it’ll sort of compel readers to go look for more coding instruction. That’s my main goal, just to kind of give them a taste of it and get them to go learn it within a classroom. And I’m hoping to cover tougher concepts before the end of the series. So it will get progressively more complex.

Do you think that there’s a possibility you’ll be able to rope in adults into coding as well? Because I have to tell you, I don’t know anything about it, like I said, but all of a sudden I suddenly have a greater appreciation for the science at least.

That’s awesome!

I at least understand binary a little bit now.

That’s awesome, that’s awesome. I hope so, yeah. We have a website, Secret-Coders.com. It’s not completely done yet, but right now we have like a worksheet you can download that kind of goes over coding concepts and I’m planning on adding more, and I’m also working on video lectures. Right before you called I was working on the script for the first video lecture, so I’m planning on having two or three for each book that comes out, so it’ll walk you through the concept that’s covered in the book.

Is your hope that this book will eventually end up in 5th, 6th grade classroom, particularly computer classes? I know First Second kind of leans toward libraries and schools..

Yeah. Absolutely. I hope so. I definitely hope so. Like I said, I don’t necessarily see it as a textbook. I want it more to be like a gateway into coding, you know? This is what I think. I think that like if you look at — Just look at Transformers, right? Transformers started off as a pure toy line. These Japanese companies created these transforming toys, but it didn’t really pick up until Marvel Comics came up with this narrative to go with the toys. So the narrative is kind of like the heart connection. It connects people’s hearts to these objects. In the same way, I’m hoping that by laying a narrative on top of the discipline of coding that it’ll be a heart connection. That it’ll give kids a heart connection to coding and make them want to learn more about it.

In volume two it looks like the kids are heading into some deep secrets in the school. Can you give me any sort of sneak preview of what’s to come in the subsequent volume?

Yeah. Well, we find out who the real bad guys are and who the real good guys are, and then the coders kind of coalesce, the three main characters, Eni, and Hopper, and Josh kind of coalesce into this, almost like a super team with like uniforms and stuff.

Oh, nice. They literally become the team that the title promises at this point.

Yeah, yeah.

Has this inspired any sort of new educational projects in you now that you’ve done this? I mean, you said you were doing something about basketball. Is that the project that you’re illustrating yourself?

Yeah. that is, that is. That’ll be my first non-fiction book. It’s about a high school basketball team that I followed last season during the ’14-’15, 2014-2015 season. So I like flew out with them for games and went to their practices and talked to the players, and I’m going to write a book about them.

Side-note, I never got a chance to congratulate you on your Eisner win this past summer, which was very exciting.

That was crazy. That’s not how I pictured that portion of the night to go, you know? Like I would not have predicted that at all. It was a shock. Even to be on that list at all in humbling.

All my favorite writers all on one list. I was rooting for you, man, but it was an impressive lineup of talent. I was just so glad that you got to — I mean, I know it’s not your first Eisner win or anything, but definitely was the big prize.

Yeah. It’s just crazy.

Is the award sitting somewhere in your office?

It is, yeah. I have it in my office.

Let me ask, have the children wanted to hold it yet?

You know, it’s actually really hard to impress your own kids. They’re just like, eh, whatever. I think my son, my oldest took a little bit of interest in it when I first got it. I put it in his hands, he’s like whatever.

“My dad, the best writer in comics, no big deal.” This year’s been a little bit of a change for you career-wise given that you’re now writing the most iconic character in comics in Superman, and I was really impressed with your panel at Comic Con, the way you were sort of ducking and weaving John Cunningham’s (VP of Content Strategy at DC Comics) questions about your run, in an attempt to keep things secret, which I really appreciated by the way.

*laughter* Well, I wasn’t sure. I’m new to DC. I don’t know what I can talk about and what I can’t. I’m still trying to figure that out.

Now that you’re working for one of the biggest companies in the industry and working with its biggest character, has it changed the way you feel about the industry in general? I mean, has it given you a new appreciation for sort of the monthly comic schedule? What’s changed?

Absolutely. It makes me admire people who are able to do this for years, and years, and years all the more. It is a crazy schedule. Oh, my gosh. Like it’s just so different. Even like — I’ve been doing these Avatar books for Dark Horse, and they’re a serial at three releases a year. It’s roughly the same as 12 months of monthly comic books, but the schedule and the pace of monthly super hero comics is just so nuts, you know? It’s kind of amazing. I do feel like I’m learning a lot simply because I have to work at this pace. But I definitely have a much deeper appreciation of like artists and writers who are able to stay in this world long term.

You get to work with some great artists on this run between John Romita Jr. and Howard Porter. It’s got to be impressive as someone who is an artist yourself to be able to work with such artistic talent. I mean, on the whole, I don’t think you’ve ever had a badly drawn book in your career.

I’ve been lucky. I feel like I’ve gotten to work with some really talented people, Sonny, and Derek Kirk Kim, and Mike are all really amazing. Every single one of them also writes, you know, and I think that helps as well. All of them have this innate sense of story that I’ve been able to trust and rely on.

Is there anything else I should make sure that readers know about either Secret Coders or about some of your future work?

Well, the next volume of Avatar: the Last Airbender will be coming out in September, same month as Secret Coders, called “Smoke and Shadow”. We’re taking the action back to the Fire Nation. We’re introducing a concept that Michael (Dante DiMartino) and Bryan (Konietzko) had when they were working on the cartoon series, of a group of fire nation women warriors, and they were never able to introduce that in the cartoon, so we’re actually introducing them in the comic. I’m excited about that.

Oh, and I just want to let you know, I was able to solve the first problem in Secret Coders with the combination lock.

Okay. Awesome!

I have not attempted the end of book puzzle yet, so that will be something I work on here at least in the next week or so in the lead up to the release. I’ll try to have some bragging rights and say I solved this puzzle before any of y’all did! So take that, 11 year olds!

Secret Coders Vol 1 is in stores today from First Second. Pick up a copy and share it with a young one in your life, it’s well worth it! I recently donated the one I received to the local library, where I hope it’ll inspire a burgeoning mind.

If you want to read more computer comics:

The Cartoon Guide to the Computer by Larry Gonick 9780062730978

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Computer by Sidney Padua 9780307908278

Build Your Own Website: A Comic Guide to HTML, CSS, and WordPress by Nate Cooper and Kim Gee 9781593275228

(And somewhere, in the back of my memory, is a fictional graphic album, published by Microsoft, about a group of young teens who solve a tech crime. No… not the Radio Shack Whiz Kids!)

Comments are closed.