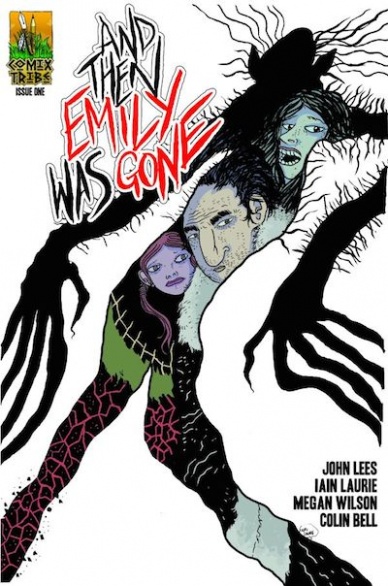

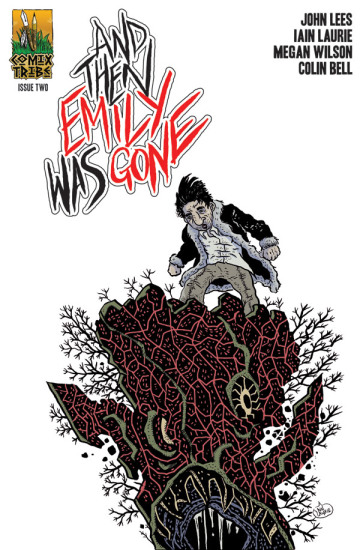

Who even is Emily and where did she go? Those are the first two questions that spring into the mind when reading ‘And Then Emily Was Gone’ by John Lees, Iain Laurie, Megan Wilson and Colin Bell. A mystery series which quickly leaps into the horrific and fantastical without a word of warning, this month sees the book head out into the previews catalogue. The first series published by ComixTribe, the series was originally published last year in black and white – however, for this second time round, it’ll be in full colour. Each member of the creative team is known for their own work, making this a bit of a Scottish supergroup thing – like The Reindeer Section! Lees is probably best known for writing superhero series ‘The Standard’, and Laurie for a whole load of books including Metrodome and Horror Mountain. Wilson can also be seen colouring Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,whilst Bell is the writer of Dungeon Fun and owner of Dogooder Comics. They’re busy people.

But they all very kindly took the time to talk to The Beat about ‘And Then Emily Was Gone’ – delving into all aspects of the creation of the book, and the journey it’s been on. With the first issue about to launch at Glasgow Comic-Con this weekend, it felt like the perfect time to take a closer look at the series. Read on!

JOHN: Well, I’ve been a fan of Iain’s for years, so I’d been wanting to work with him for some time: it a quite large-scale anthology with a pretty big publisher interested, and had enjoyed that taste of the partnership. So, when that project stalled, Iain and I decided we were going to develop a comic of our own to work on together. And so what made this the project we decided to collaborate on is that, from the ground up, it was something we cooked up together as essentially our dream project, a mash-up of a whole bunch of ideas and influences that we shared a passion for.

IAIN: I saw a copy of The Standard and was really impressed. I was trying to move away from the more experimental stuff I’d done with Craig Collins or on my own with Powwkipsie and Horror Mountain, and I thought John would be the best guy to do that with. Luckily he wanted to do something with me. In terms of collaborating on this, it’s very much everything that both of us are into thrown into a meat grinder really.

Where did your respective interest in horror stories come from?

JOHN: I’ve loved horror for as long as I can remember. Monster Squad was an early favourite film in my house, and one of the earliest toys I can remember having was of Frankenstein’s Monster. Me and my cousin were equally mad for scary movies at a very young age when we really should have been watching cartoons, and while other kids were playing Cops & Robbers or Soldiers or whatever, my cousin and I would play “Horrors,” where he’d pretend to be Freddy Krueger and I’d pretend to be Chucky from Child’s Play, and we’d take turns murdering invisible victims. I had a very happy childhood, it was only fucked-up in retrospect!

IAIN: I’m not a huge horror guy in the traditional sense but a lot of what I do is influenced by being a teenage Stephen King fan. I really like the idea of the horror beneath the surface stuff he was so good at. And that also plays into my love of David Lynch too. But most modern horror leaves me pretty cold.

Is it difficult to translate a horror experience to comics? Is there still a capacity to shock and startle within a comic page?

IAIN: If I’ve got a technique its always to try and make something that looks like a normal comic but isn’t, so your mind traditionally expects a certain progression of the story and framing choices – close-up, wide shot – that reflect the story and the intentions of the writer and artist. By refusing to follow this it unsettles the reader. So if you have a really intense scene where you would expect a close up if you instead use a long shot it throws you and you’re not sure why. Hopefully that makes sense a bit.

JOHN: It’s certainly a challenge. Much of the power of horror books comes from the words inspiring you to imagine in your head something far more terrifying than any visual that can be reproduced, but comics are a visual medium and so you have to create something that’s as terrifying as what the reader pictures in their mind’s eye in order to be successful.

In the American comics industry there’s been a flourishing of genuinely frightening horror in recent years, with Echoes by Joshua Hale Fialkov and Severed by Scott Snyder, Scott Tuft and Attila Futaki immediately springing to mind. I think something that is an effective strategy in horror across all mediums is to make your audience uncomfortable, to make them feel like they’re in a world that isn’t quite right and where something horrible could be waiting around the corner.

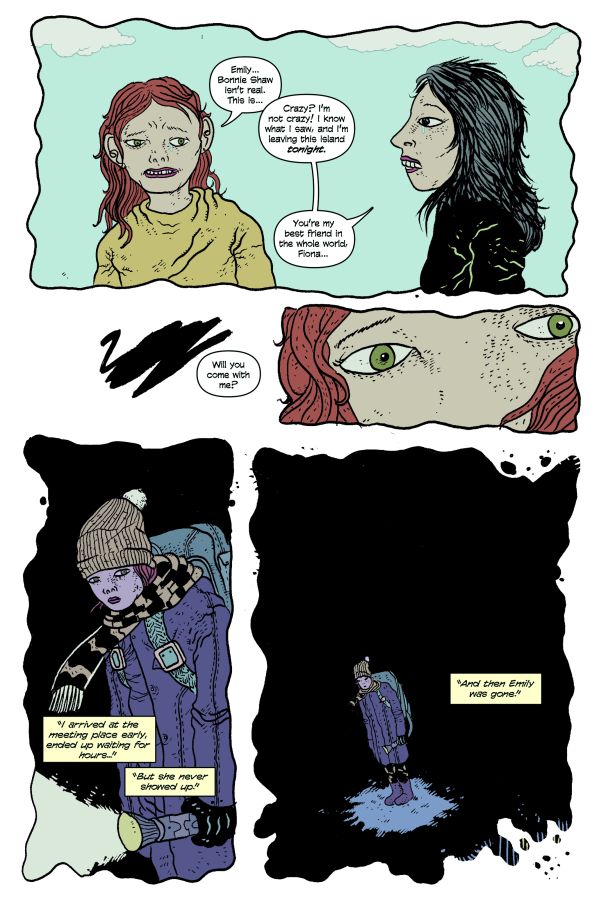

And that’s what we’ve tried to do with And Then Emily Was Gone: create a comic that reads like a bad dream, drifting gradually deeper into nightmare.

What has the collaborative process been like, as a whole, for the story? Were there any points where you surprised each other with where you took the narrative?

JOHN: Working with Iain Laurie has been an absolute joy. Because we co-created this comic and developed it together, when I was scripting each issue I constantly had an eye to thinking up stuff I, as a fan of Iain’s, would be excited to see him draw. Some of that was hoping to stretch him and have him tackle stuff that was a little different than his previous output, but a big part of it was relishing in writing “Iain Laurie’s Greatest Hits,” repurposing some of the most notable recurring motifs in Iain’s unique body of work.

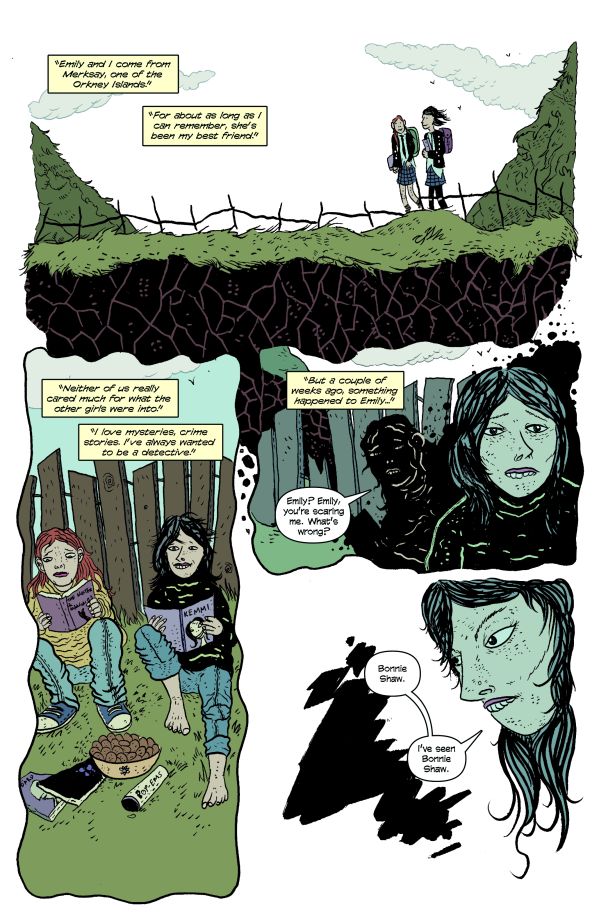

But even so, Iain has managed to constantly thrill and surprise me in the pages he’s sent back, taking my weird ideas and pushing them so much further into the realm of bonkers invention. There’s one page in issue #1 where the script says, “Close-up of Hellinger, looking worried,” and what I got back was this jaw-dropping collage of Greg Hellinger and the monsters that hound him. There’s been loads of experiences like that, Iain finding grimy little details between the scripted panels and blowing them up to add a whole new dimension to the storytelling, or portraying a bit-part character so powerfully that I want to go back and write a bigger role for them!

IAIN: Yeah it’s been great, and I’m not the easiest person to work with as I’m sure anyone I’ve worked with in the past will tell you. I very much like to do things my own way which can annoy writers and I totally get it but with John it’s been a really great time. I think were both aiming for the same things so while we might argue about directions, we both want to get to the same destination.

MEGAN: I’m jumping in here too. There is this one particular panel in issue #3 that comes to mind where John wrote something seemingly normal in the panel description and what Iain translated it to was hilariously bizarre. It stayed true to what John’s script was trying to convey, but I have no idea where Iain came up with his interpretation of it. You guys completely feed off of each other and it turns into this wonderfully charming collaborative thing and I wish everyone could see the scripts to really see this dynamic.

COLIN: Having known Iain and John and their respective work prior to Emily it’s been really fun to watch the two of them bounce off each other and see the effect this has on what they produce. Iain’s artwork, at least for the first couple of issues, is the most restrained I’ve ever seen from him, played totally straight – and I mean no disrespect to the vast body of his wild work that we all fell in love with prior. It’s like there’s an insanity, caged, just bristling to get out, and it’s unnerving – which is the desired effect, I’m sure. Meanwhile, John’s scripts feel like Iain’s work has goaded him to being the most evil, terrifying, horrific version of himself. It’s fascinating.

JOHN: While that central mystery of “Where is Emily Munro?” is the through-line that spans across the series, I’m not sure if I’d go so far as to say that the whole story is built around it. While we’ve billed And Then Emily Was Gone as a horror mystery, I’d certainly say the pendulum progressively swings more and more towards horror as the narrative unfolds. While I love a good whodunnit, I feel like the problem with many serialised mysteries is that they are most interesting at the beginning and the end, while what happens in between can be a lot of going through the motions with false leads and red herrings. I wanted to avoid that here, so I’d say it was more the desolate atmosphere of Nordic dramas like The Killing that we incorporated rather than the plot mechanics.

What interested me was the notion of stepping away from that procedural element, and crafting a mystery that would only become more horrifying and unknowable the deeper you dig into it. I’d say the focus is more on the characters and their deeply damaged headspaces. If anything, it was them – Hellinger, Fiona, Vin – that were our starting point, fully formed as individuals, and the plotting from there was more about what dark places we wanted to take those characters.

What prompted the idea of incorporating Scottish folklore into the story? Was part of your intent to make this a uniquely Scottish storyline?

JOHN: It certainly was for me. I wrote a graphic novel called Black Leaf, in the process of being drawn by Garry McLaughlin, which was another Scottish horror, set in the Scottish Highlands. And Then Emily Was Gone takes place on a remote island community in Orkney. I just feel like Scotland is such a fascinating, diverse country with locations rich in storytelling potential that has been largely untapped. And given that Iain and I (and Colin) are Scottish, why not make the most of that and inject a unique flavour into our comic that might set it apart from its American counterparts?

Iain, I read your interview with Multiversity where you said that your artwork was inspired by, amongst other things, Reeves and Mortimer. And it’s noticeable – they have that same mix of dark comedy, surrealism and a little horror which marks your style. How have you found the balance of horror and comedy within the story? Is it a difficult line to balance?

IAIN: Yeah, I’m pretty open about the fact that the biggest influences on my work are Reeves And Mortimer, David Lynch, Dennis Potter. Creepy blue-collar surrealism. In terms of Emily, I don’t really see any comedy in there. Other people have told me they find it funny but I’m never going for that. To me it’s a bit like Chris Morris’ JAM in the sense that some people found it hilarious (me) while others thought they were watching something really disturbing.

IAIN: Yeah absolutely. This plays into my earlier answer of throwing the reader off by not giving them the panel or the facial expression they expect. Again, I take a lot of this from film directors. My drawing styles got a million influences from Ken Reid to Frank Quitely to Peter Howson but my framing is very much influenced by movies rather than comics.

There are a series of strange characters in the book, marked by Iain’s sense of facial design. Where do you begin with a character? Do you bounce ideas back and forth – the scripted personality affecting the design, the design then deepening or changing the scripting, and so on?

JOHN: I would say the process of character design was very much a symbiotic one. With the main characters, Iain and I started off by talking about them, their role in the story and their personalities. Based on that Iain did some sketches, which were so evocative that they’d further inform those characters and give them a voice in my head. And that translated into how I’d write them in the script. Then when it came time to draw them on the page, Iain would often further refine his design of those characters based on how I’d written them.

With supporting characters who we perhaps discussed less beforehand, and whose roles in the scripts were more limited and functional, so much of their personality comes from how Iain draws them. There’s no such thing as a background character in Iain’s artwork: every character, even ones who only appear in one panel, has a story written into their faces. A lot of the time, it’s hard to tell where I end and Iain begins when it comes to these characters… we’re like a comic Human Centipede!

There was a certain starkness in the black and white version of the series. What prompted you to bring in Megan Wilson as colourist?

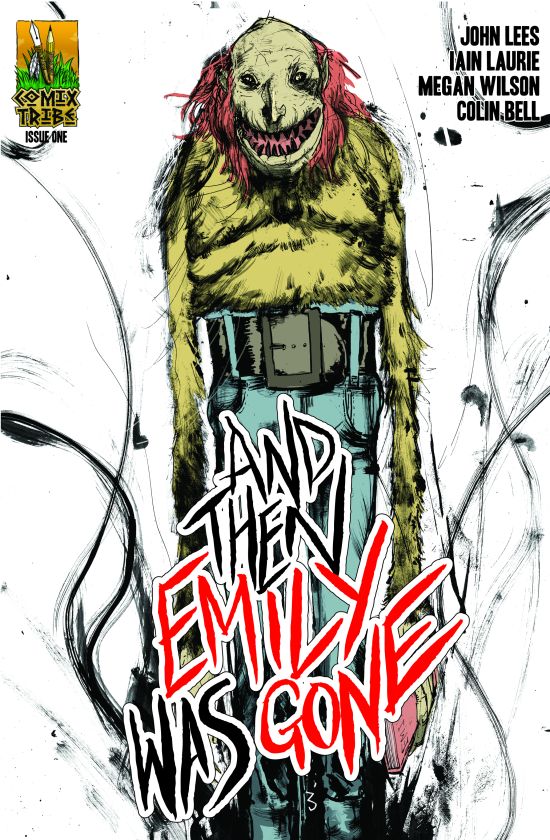

JOHN: It was actually Nick Pitarra’s idea! Iain and I had originally envisioned the comic as being black-and-white, and had produced the first issue with that in mind. Iain had been showing pages to Nick, who’s been incredibly supportive of the book and a major cheerleader for us. While we thought this would be a little personal comic destined for the British small press scene, Nick was perhaps the first person to suggest that And Then Emily Was Gone could work in the American market, and that colouring it would make it more appealing to that demographic.

And so he suggested letting Megan Wilson, who he’d worked with before, try her hand at coloring. And the rest is history. Looking at the book now, with Megan’s spectacular covers and how they compliment Iain’s art, I can’t imagine the series without her now.

IAIN: Yeah, Megan’s amazing. I love how her stuff complements my drawing.

MEGAN: This is probably a weird part of the interview for me to add to, but whatever. You guys always have such wonderfully nice things to say in interviews about me and this is the first opportunity I’ve had to chime in, so I just wanted to add that YOU guys are amazingly talented and infectiously enthusiastic and I’d be happy to work with you forever and always.

JOHN: Megan has become an integral part of the creative team. She’s the ideal tag team partner for Iain, as her colouring seems to fit Iain’s art like a glove onto a gnarled, clawed hand. When I’ve seen Iain’s stuff coloured in the past, it sometimes seems like the effect has been to mute the weirdness of the linework and make things a bit smoother and more palatable. Not so for Megan, who has brought this askew, almost rotten aesthetic to the colours with sickly, grainy shades that actually accentuates the inherent “Laurieness” of the image. Looking at the book now, with Megan’s spectacular colours and how perfectly they compliment Iain’s art, I can’t imagine the series without her.

IAIN: Yeah exactly. It just plays into how I want the book to be read, beautifully. She’s a wee genius.

Megan, is it daunting to work colours on a comic which has previously been released in black and white, or do you enjoy that challenge?

MEGAN: I live in the US and have still never seen a hardcopy of the B&W version so I actually hadn’t thought about this before – of course I’ve seen the original B&W as digital, but I suppose that doesn’t have the same impact since scans are always my starting point.

It can be daunting to realize there is an existing fan base and that you could do something that they completely hate, but I elbowed my way into the project because I loved it and wanted to be a part of it, so I guess the worrying part became somewhat irrelevant (notice I didn’t say non-existent!). But yeah, I guess I’m up to the challenge!

How did you develop the colour palette for the series? What were your aims as a storyteller?

MEGAN: I probably shouldn’t admit this, but I didn’t really develop a specific palette for this, I just kind of make it up as I go. I’ll go back and grab colours off of pages from earlier pages as needed for consistency, but other than that, it’s pretty much a free for all. From a storytelling perspective, to me this felt like an escalating fever-dream, and so the colours start to get a little more weird the further into the book you get.

And Colin, how do you approach lettering horror? Do you find that you have to work in specific ways in order to maintain or enhance that atmosphere?

COLIN: It was a conscious decision to utilise lower-case lettering because there’s a kind of innocence to it that I thought would play well against the art and lull people into a false sense of security. I can echo Megan in the sense that as the issues progress, I’m able to crank up the weird factor to accentuate what’s happening on the page. Also worth mentioning is the logo for the book. When we started we talked about these filmic covers like movie posters, and it inspired me to go down the rabbit-hole of 80s horror movie poster typography.

When there were no typefaces that really sold what we were going for (or were basic pastiches of existing horror film typography), we got Iain to scrawl the title in his own inimitable terror-screed, which I tidied up a bit, coloured and now happily slap across every cover sent my way. I feel like knowing that it’s Iain’s handwriting on them lends a kind of unity to his covers as a whole. But really it’s just my job to try and help guide the reader’s eyes where appropriate and for the most part stay the hell out of the way of Iain and Megan’s work, which I’m very happy to do.

Alternate cover for issue #1 by Riley Rossmo and Megan Wilson

There’s an interesting group of Scottish comic-makers right now, with yourselves, the Master Tape team, Team Girl Comics, Dungeon Fun, and many others. What has been your experience of this Scottish community?

JOHN: Scotland is certainly a major comics hub, and my native Glasgow is a great comics city: not just in terms of the dedicated readers – enough to support 9 comic shops, 2 comic cons and multiple marts, clubs and public events – but also in the volume and quality of creative talent. I’m a founding member and the current chairman of the Glasgow League of Writers, a kind of writing circle for comics where creators meet to discuss and critique each other’s scripts, so I get to see first-hand some of the amazing talent in the Scottish community.

Iain McGarry is a writer who’s been quietly producing some excellent short stories for various anthologies over the past year or two, and once he collects them all into a volume of his own and gets his name out there some more, he’s going to become a big deal fast, mark my words. John McCusker is like 21 years old, was totally new to writing comics when he first joined, and already he’s better than me. His debut book, The Alchemist, is in production with artist Jason Mathis, and is going to be incredible. You mentioned Master Tape, and Harry French is another guy primed to blow-up: his other series, Freak Out Squares, is even better. And Freak Out Squares artist Garry McLaughlin is also kicking ass on his own series, Gonzo Cosmic.

NeverEnding, by Stephen Sutherland and Gary Kelly, is a hidden gem of a comic which should be getting distributed by a big publisher yesterday. Gordon McLean won a SICBA award for No More Heroes, which was ace, but the stuff he’s been quietly working on since is so much better. Dungeon Fun by the sublime Neil Slorance and our own Colin Bell – the first issue was one of the best single issues produced by anyone of any level last year.

Team Girl Comics, Black Hearted Press, Unthank Comics, there’s so much going on I can’t hope to cover it all.

IAIN: Yeah, there’s so much interesting and diverse stuff coming out of Glasgow, and I think John’s covered most of it. I live in Edinburgh and older than most people in that group but they’ve always been really welcoming and friendly to me.

MEGAN: I’m completely jealous of the vibe you guys have got going on over there. Can someone please adopt me so I can be Scottish too?

JOHN: Working on this comic has made you an honorary Scot, Megan!

COLIN: Congratulations Megan! The Broons are your Gods now. My experience of the community has been nothing short of lovely. Everyone’s dead nice. And talented! I could sit here for ages and reel off so many Scots comickers deserving of attention we’ve not mentioned yet – Craig Collins, Edward Ross, Stephen Goodall’s IMR, Chris Baldie and Holley Mckend’s Never Ever After… there’s LOTS.

Do you feel there is a movement in Scotland, and the UK as a whole, where different groups of creators are all starting to rise up together? Even Colin Bell?

IAIN: Colin Bell is the sun we all revolve around.

COLIN: Shucks. But also, correct.

JOHN: EVEN Colin Bell!? He’s going to hit the big-time quicker than any of us. He’s already a comics mogul who seems to have lettered just about every comic in Scotland and now half the comics in the UK as a whole. As for whether or not there’s a movement with groups of creators all rising together, I’d say, “yes and no.”

Yes, there are many indie creators – both in Scotland and the UK as a whole – on the cusp of breaking out, producing quality work, and I take pleasure in seeing their successes, but ultimately everyone is doing their own work, and I think most would rather get recognition based on the merits of that work rather than through riding the wave of a movement. Though I’d say the one exception is that I’m happy to ride on Iain Laurie’s coattails to comics glory!

How did ‘And Then Emily Was Gone’ find a way across to ComixTribe, who’ll be publishing this five-issue run?

JOHN: I worked with ComixTribe on my debut comic, The Standard, and that experience has been a pleasure and a privilege. You won’t find a more passionate, professional group of people than Tyler James, Steven Forbes, Joe Mulvey, Samantha LeBas and co at ComixTribe, and they’re super-nice people too. Anyone who works with them once would want to work with them again in a heartbeat, so when the opportunity presented itself I jumped at the chance to pitch And Then Emily Was Gone to them.

They’re the kind of publisher who will get behind their titles and their creators 100%, and given that a comic as weird and out-there as And Then Emily Was Gone might not be the easiest sell, I wanted that kind of support network behind us. ComixTribe took a chance on us, and thankfully that seems to have paid off, as initial Diamond order numbers suggest that And Then Emily Was Gone #1 will be the biggest first issue Diamond launch they’ve ever published!

How do you feel about the story, as a whole now, looking back across it as it heads to the new colour printing

IAIN: Well I’m still drawing #5, so I’ve not had time to reflect yet!

JOHN: Looking back at the story as a whole now, which at the time of this interview has been 100% written and 80% drawn, I’d say this could be the proudest I’ve been of any comic I’ve ever created. I don’t know, choosing between this and The Standard is like choosing between my children! But with The Standard, right from the beginning I approached it with this goal of escalation, of having every issue be better than the last building up to a blow-out final issue that was the best of the bunch. And I think I’ve been consistent with that in my approach to And Then Emily Was Gone.

Looking back, as a reader, I feel like each issue is not only better than what came before, but darker too, scarier, and by the time you get to the last couple of issues hopefully it’ll be a bit of an onslaught. As I touched on above, the story starts relatively grounded, but steadily gets scarier and more bonkers with each passing chapter!

MEGAN: I’m in last place here (colouring #4) and I have no idea what happens in #5 yet since I have been purposefully not reading ahead so I can experience the story and art together. That being said, I’m really excited to see how this all wraps up!

COLIN: Well, I’m after Megan, but having been in the Glasgow League of Writers I’ve been privy to the scripts for the whole series. I’m still recovering.

What are you working on next? Where can people find you online?

JOHN: I’ve got more work with ComixTribe on the horizon. I’m currently co-writing Oxymoron: The Loveliest Nightmare with Tyler James. It’s a spin-off from Tyler’s comic series The Red Ten, taking the villain from that book – masked psychopath The Oxymoron – and removing all superhero trappings and dropping him into more of a crime procedural milieu where regular cops have to deal with this larger-than-life, monstrous master criminal. Alex Cormack is on art duties, and the pages I’ve seen thus far are delightful. Looking further ahead, Iain and I have also been talking about further collaborations, since we had such a blast working together on this.

In general I’m looking to do more work in the horror genre. As for where you can find me, there’s the official blog for And Then Emily Was Gone. You can find out about my other comic, The Standard, while my personal blog is here. You can follow me on Twitter, and can follow And Then Emily Was Gone on Facebook here.

Remember, And Then Emily Was Gone #2 is currently available to order in this month’s Previews, order-code JUN141021, and you should still be able to order issue #1 – due for release July 30th – with the order-code MAY141251!

IAIN: Next thing for me is a story with Sam Read (Exit Generation) for Grayhaven, then a Standard story with John and a few other things in the wings with Owen Johnson (Raygun Roads) and Tim Daniel (Curse) hopefully. And then onto the sequel to Emily: AND THEN EMILY WAS GONE AGAIN, where they all go on holiday to Spain!

–

Right! This is me, Steve, back again. A few extra credits and links for you, because there’s so much more still to find! You can also find Megan Wilson’s work over on her facebook page, as well as on her twitter account right here.

Colin Bell, meanwhile, will be launching Dungeon Fun Book Two this weekend at Glasgow Comic Con, and is also the letterer for a number of projects – Exit Generation #2 being one of the most recent. You can find him on twitter here.

Many thanks to the whole of the creative team for being so generous with their time in the interview. I hope you enjoyed it! As mentioned above, issue #1 of And Then Emily Was Gone will be released on July 30th.

Looks interesting. Is there any place I can read a preview?

I’ve been told there will be as the series gets closer to the publication date – the pages here are all from the same issue, and hopefully work as a preview until then?

Yes, look for an official preview on the Visit Merksay blog later this month! In the meantime, here is an article from a while back that includes a preview and a trailer:

https://medium.com/@TylerJamesComic/comixtribes-horror-mini-series-and-then-emily-was-gone-terrifies-in-july-3aff7cf5ab4

yes, yes, the coloring tonal palette is so bla bla bla, … the lettering is so subdued… the writing is so fine and scary, bla bla bla… Let’s be honest: there is only ONE reason anybody knows about or even bothers to look at this fine book. Can you think what that reason is? That’s right… (no disrespect, but don’t go on and on about yourselves, writers/colorists/letterers it’s a little embarrassing…)

Comments are closed.