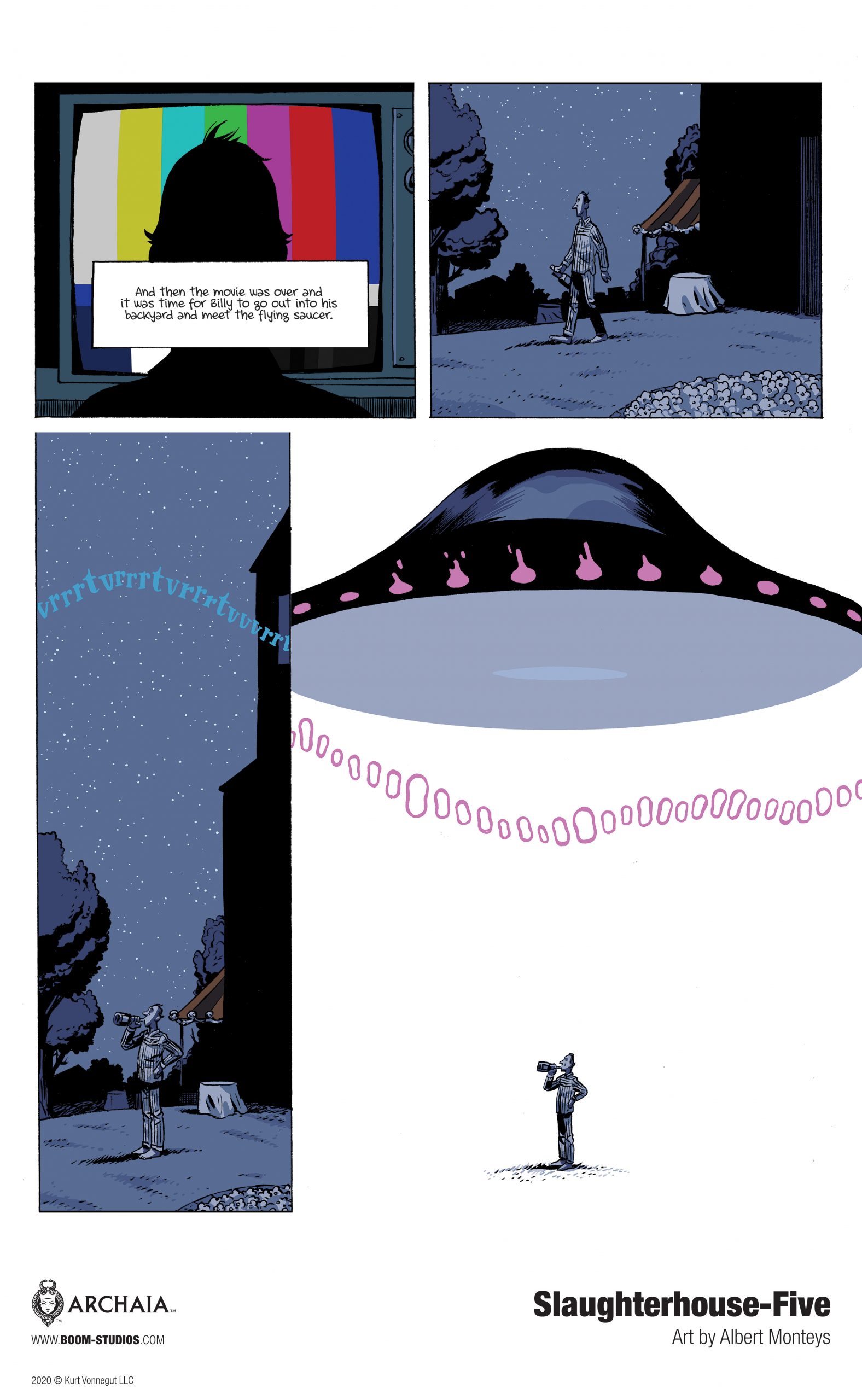

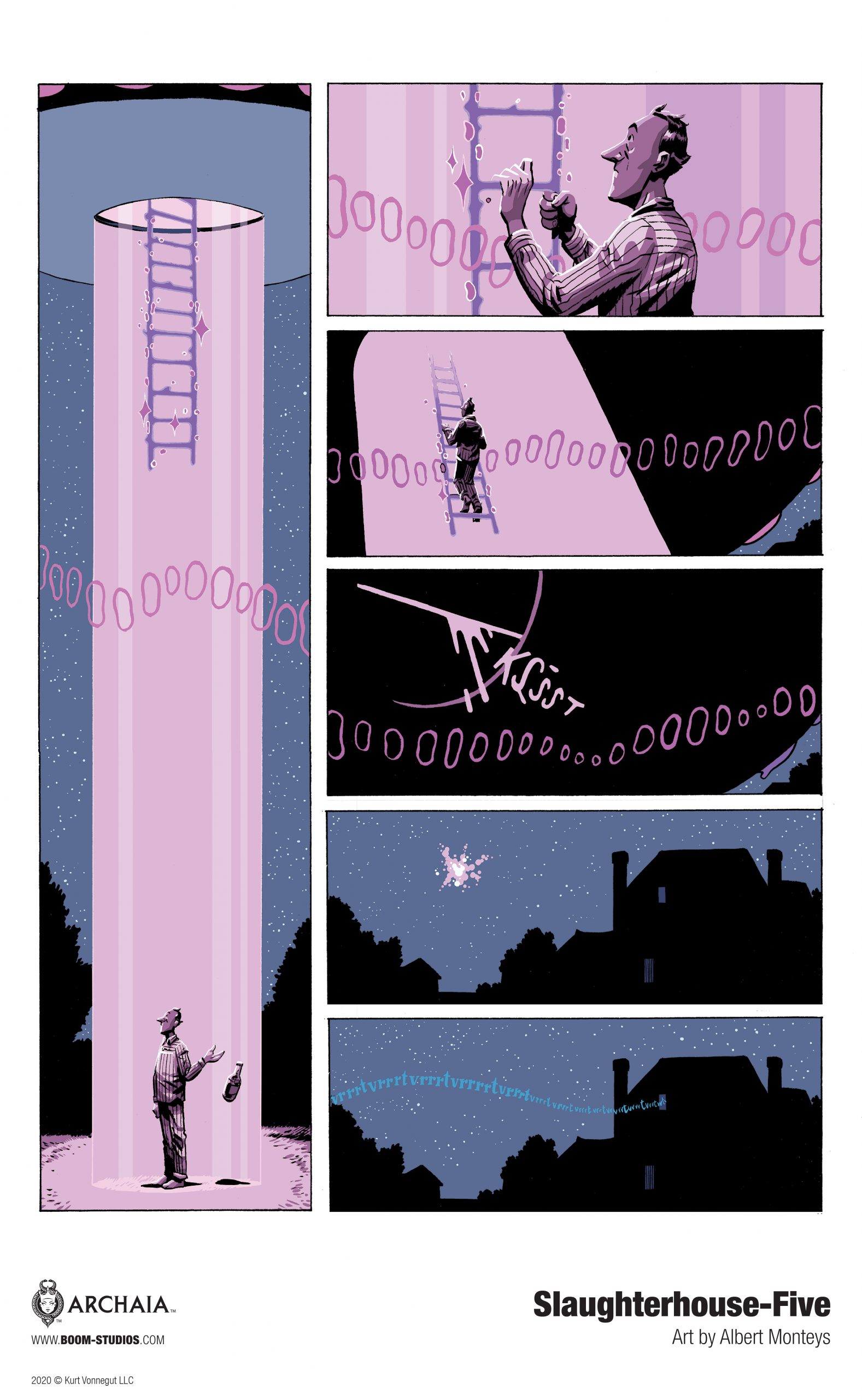

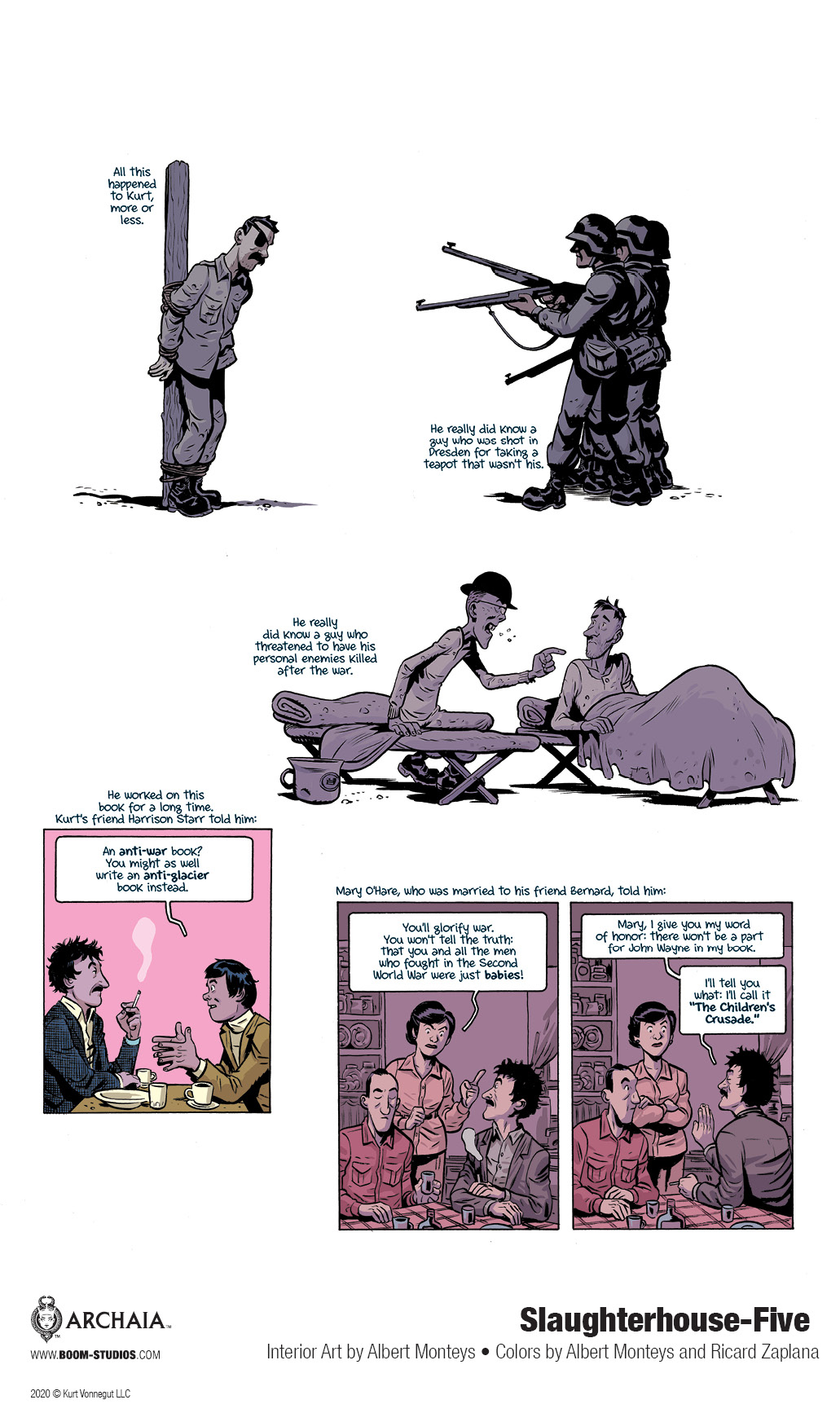

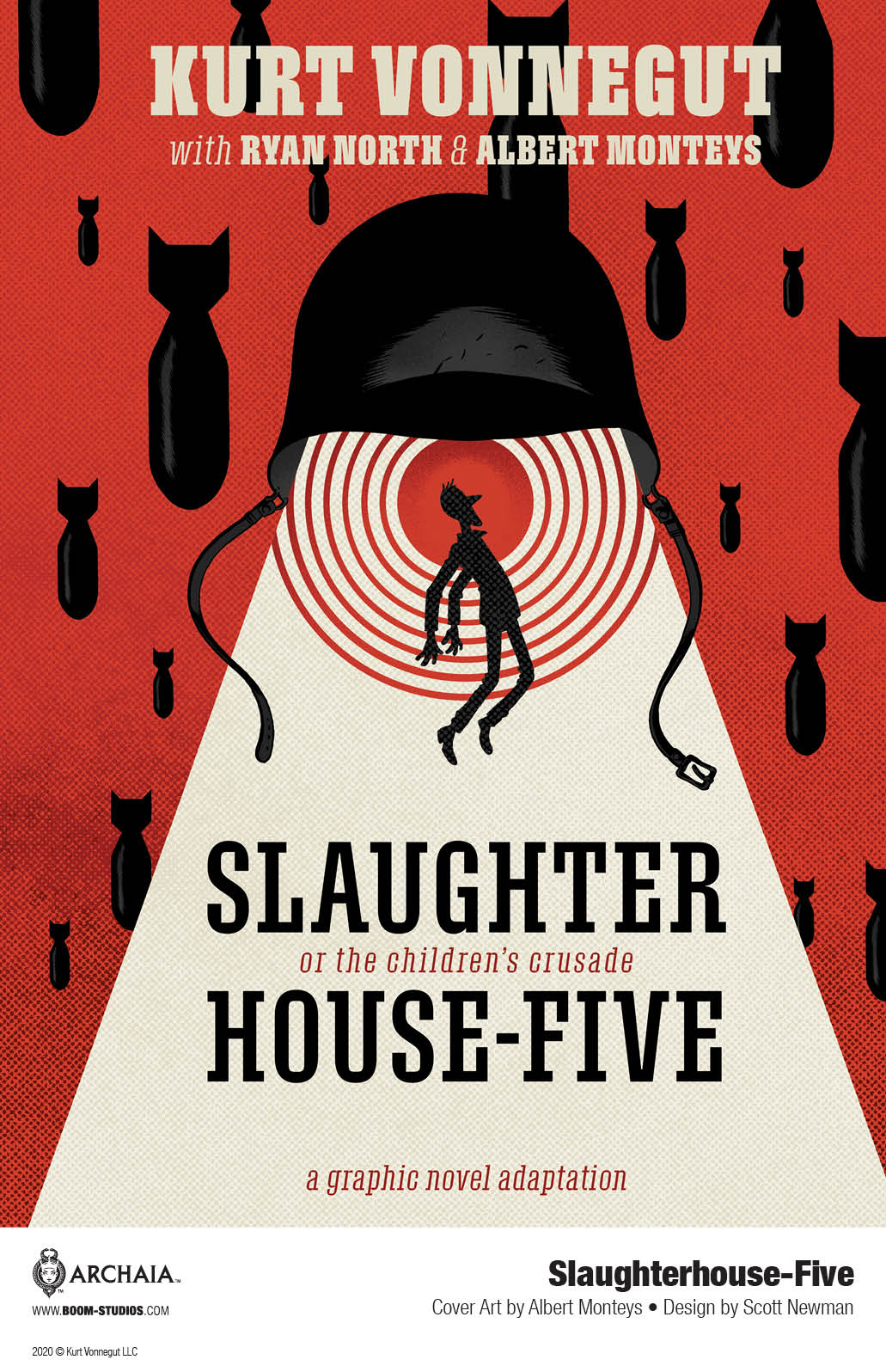

In March 1969, Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death was published. Based on his personal experiences as a prisoner of war during World War II, where he bore witness to the firebombing of Dresden, the novel includes science fiction elements like a protagonist literally untethered in time and the extraterrestrials known as the Trafalmadorians.

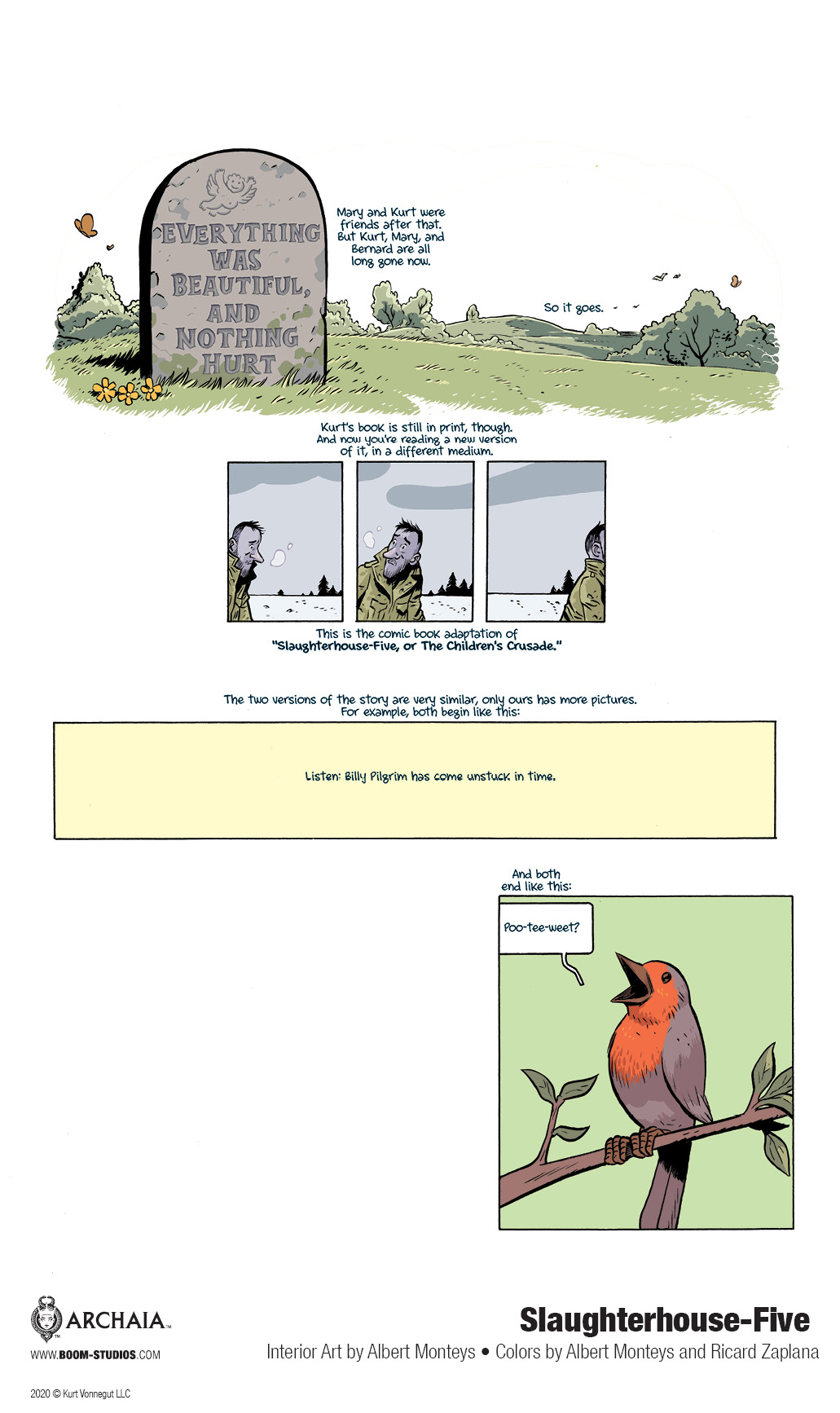

Today, the graphic novel adaptation from BOOM! Studios is available in comic shops, book stores, and at your local library. The adaptation was written by Ryan North, with art and colors by Albert Monteys and color assistance by Ricard Zaplana.

The Beat caught up with North over email to find out more about the process of adapting Slaughterhouse-Five.

AVERY KAPLAN: What is your personal history with Vonnegut? Did you have a specific story about how you discovered his work?

RYAN NORTH: I still have the first Vonnegut book I ever read, which was a paperback copy of Slaughterhouse-Five given to me by my friend Priya. She put a Superman sticker on the back to cover up the price tag. I read it right away – actually, I started reading it on the way home from the post office – and I still remember the moment, there parked in my car, putting the book down to look out at the night and the empty lot. The book demanded it, demanded that I take this moment to let it sink in. I’ve never had that before or since – normally I just tear through things. So adapting this book into a new medium was a very special thing for me. You know, on top of it being Vonnegut’s most famous and influential work, which was also a thing.

KAPLAN: How did the process of adapting Slaughterhouse-Five (a more straightforward adaptation) compare with the process of adapting Romeo & Juliet or Hamlet (more unconventional adaptations like Romeo and/or Juliet)?

NORTH: It’s interesting, because I actually consider Slaughterhouse to be a very non-straight-forward adaption! With me turning Shakespeare into non-linear choose-your-own-path books, that’s a new medium, but it’s a much more adjacent medium – and also, Shakespeare has been adapted so often that it felt safer, almost? But Vonnegut adaptations are more rare and there’s never been a graphic novel version, so this felt like uncharted territory, and I definitely 100% did not want to mess it up.

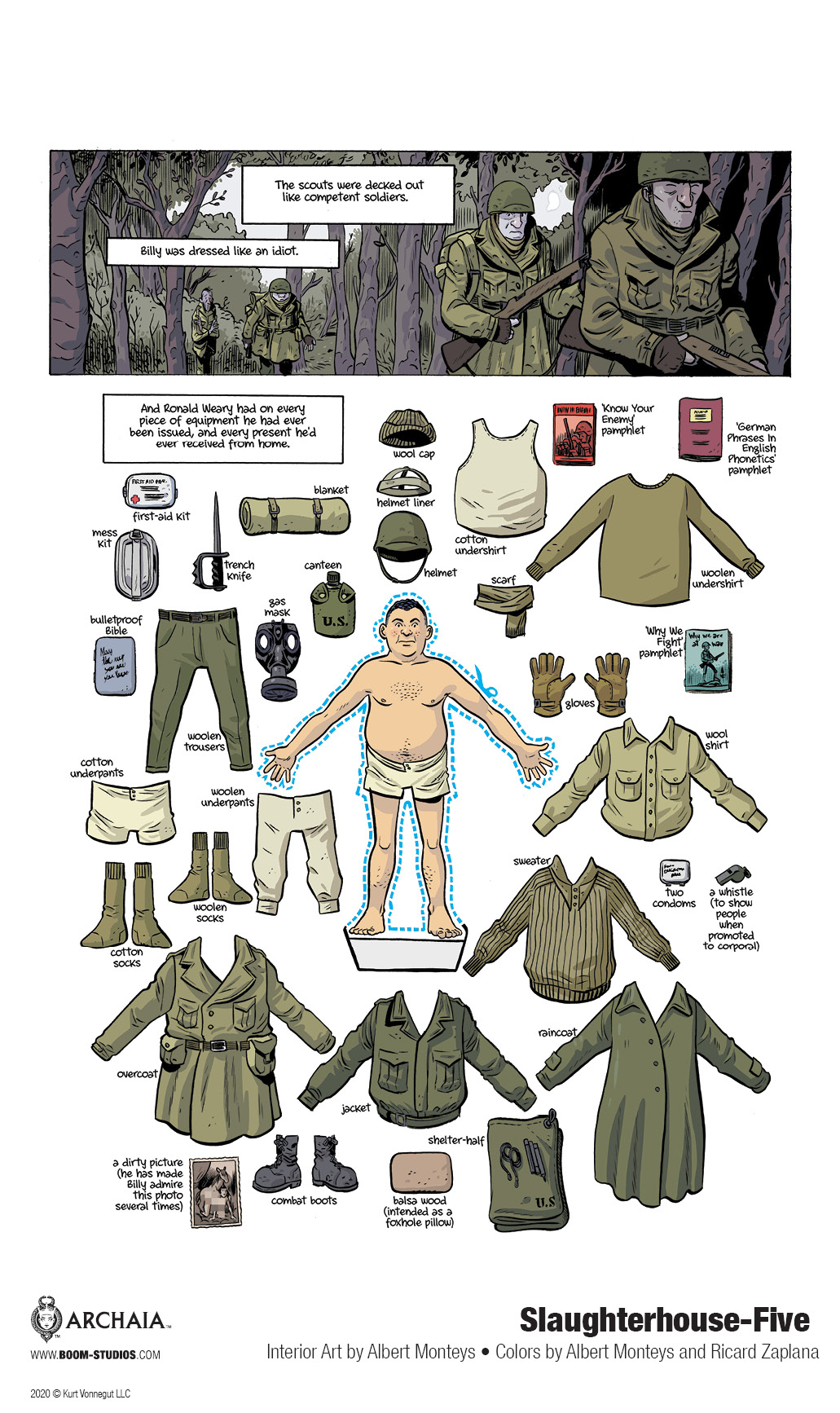

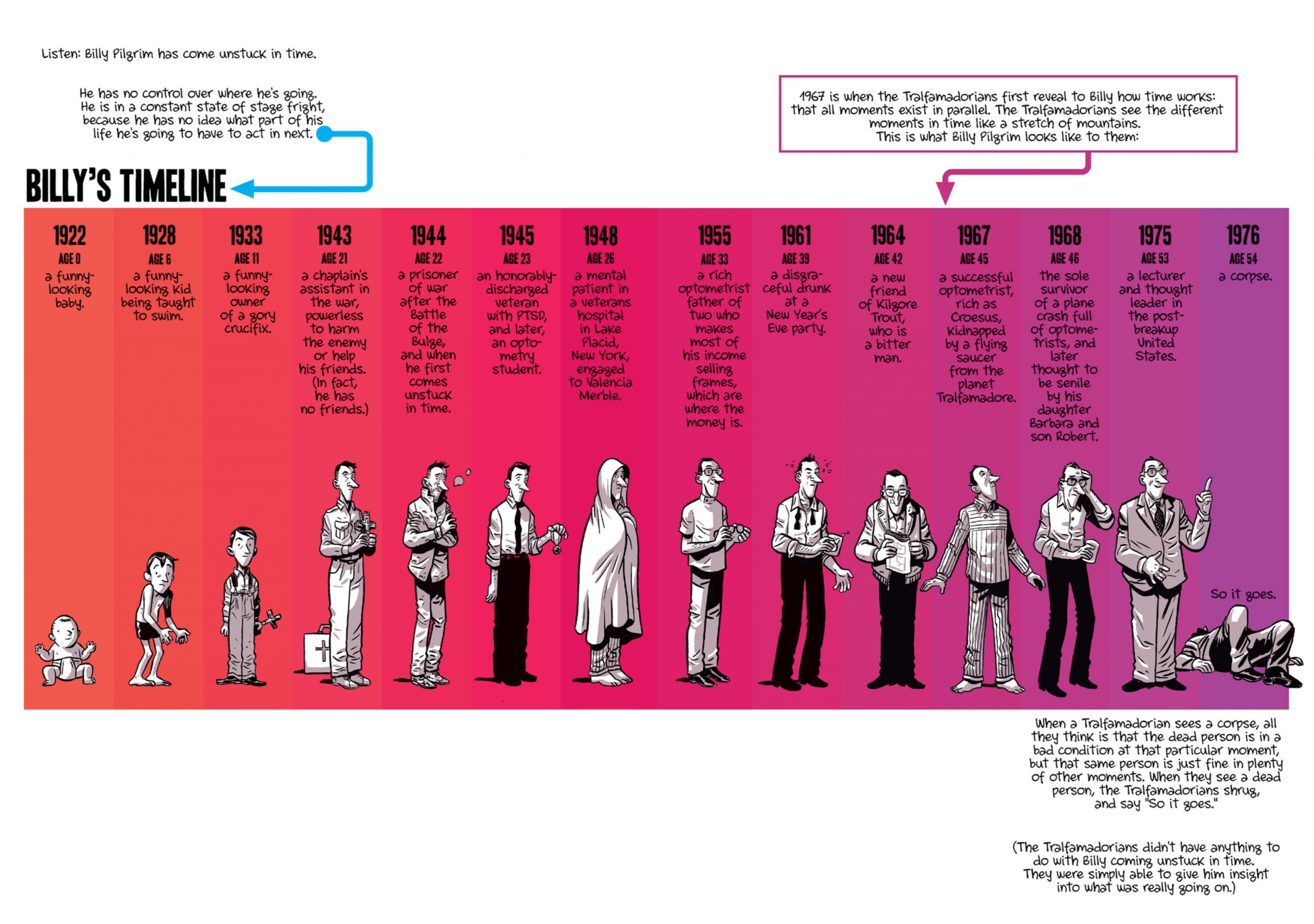

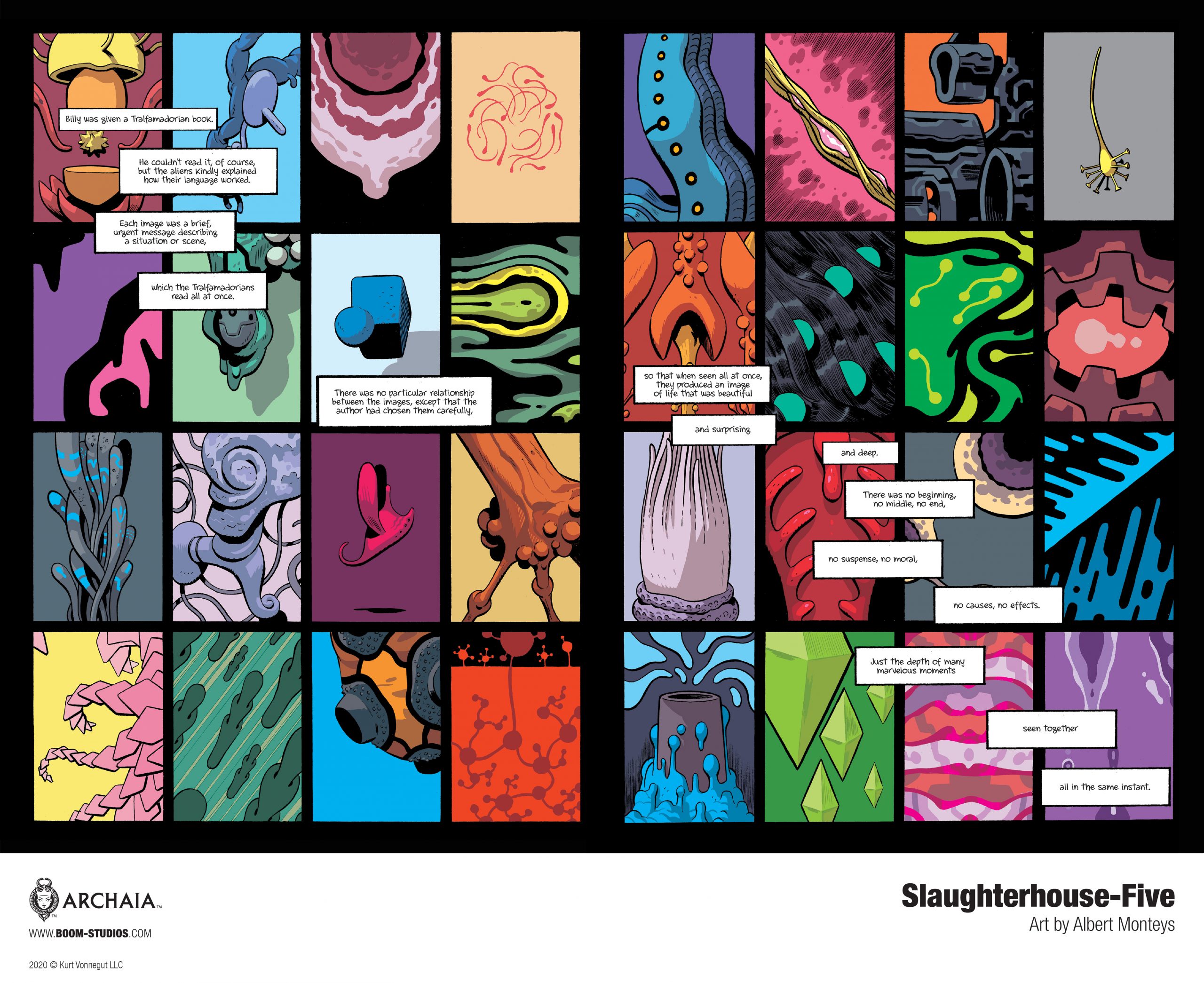

My overarching goal with the book is to make it feel at home in the medium, like it was born there first, so if someone had somehow never heard of Slaughterhouse-Five, they could read this comic and think “oh wow, that was a great comic” and not “oh weird, what an odd way to experience the prose novel, which I will now check out to complete the story I have experienced.” So a lot of the work was coming up with ways to express things in a comics-native way that were expressed otherwise in prose. Weary’s paper-doll cutout page, the Tralfamadorian book two-page-spread, Derby’s narration boxes occluding his balloons, the way we showed Billy’s backwards movie: all of these were solutions to that problem, solving it in ways that it could only be solved in this particular medium we all love.

KAPLAN: Adding comics to Kilgore Trout’s body of work (and including the excerpts) is an especially adroit bit of cross-media adaptation. When and how was the decision made to have Trout be a comics writer?

NORTH: Hahaha, thank you! I really liked the meta-joke of it: that Trout is this failed scifi writer, like in the prose novel, but now he’s failed so hard and so completely that he’s moved downmarket into comics. It fits Trout so well, and also is a little wink at the way comics have been considered a few decades ago: this disposable fare for children that now, of course, the presumably non-child reader is enjoying.

But it also worked really well structurally: in Slaughterhouse-Five we get to experience several of Trout’s stories, and while Vonnegut basically summarizes them, I thought it’d make perfect sense to show them as comics, but pulpy Golden-Age comics: something that would stand apart from the rest of the text but also fit in well to the times and the genres in which Trout writes. Once I started exploring the idea it felt quite natural, and Albert did such an amazing job rendering it authentically. They’re some of my favourite sequences in the entire book!

KAPLAN: You’ve written for established extended universes like Marvel, which may involve writing characters who elsewhere headline their own stories. Was writing for characters like Eliot Rosewater and Howard W. Campbell, Jr., comparable? Did you look to other Vonnegut novels like Mother Night, The Sirens of Titan, and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater while working on the adaption, or did you solely focus on Slaughterhouse-Five?

NORTH: I’d had the fortune to have already read most (all?) of Vonnegut’s work, so I’d already done the “homework”, so to speak, on the Kurt Vonnegut Extended Universe. And while characters like Trout and Rosewater do show up elsewhere, Kurt’s never too precious about continuity or making sure it all lines up, which took some of the pressure off – it’s not like the Marvel Universe, where everything is supposed to connect to everything else and always make sense, and you get in trouble if you kill of Spider-Man in your talking squirrel comic (not that we ever did, BUT). Anyway, that said, Kurt’s writing is always about empathy and how human everyone is, and even these supporting characters here in Slaughterhouse can have these full and interesting lives elsewhere, so knowing how they were when they took on starring roles helped me write them in these supporting ones. And it was the reason I slipped in that one line that’s also a title drop (“God bless you, Mr. Rosewater”) into the comic. Sort of the sequential art equivalent of Nick Fury meeting Tony Stark at the bar, I suppose, only much way more subtle!

KAPLAN: Speaking of the Marvel Comics universe, in The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl #30, the Trafalmadorians are mentioned twice. Which Marvel hero would the Trafalmadorians be most likely to abduct?

NORTH: This is a question I’ve never been asked before – perhaps it’s one nobody has ever been asked before? – so I’ll say that they’d probably abduct a nobody with no connections – like Billy – simply because those people seem to be the ones that are the most interesting to them. But then again, if the Tralfamadorians are going to abduct someone, they’ll certainly tell you that they already have done it, and they already will do it again, and nothing we can say or do will change that. The moment is simply structured that way!

KAPLAN: Slaughterhouse-Five is an incredibly faithful adaptation of the source material, especially in terms of structure and language! I did notice that you updated a few lines to include more contemporary, inclusive language. Was there a discussion that arrived at the decision to update this language?

NORTH: It was, it was actually there in my very first pitch for the book! My reasoning was this: language changes all the time, and terms that were more acceptable in the 1960s certainly don’t work now. Including them out of a sense of faithfulness and authenticity only results in you hurting people and even knocking readers out of the story as they trip over words that wouldn’t be said today, even by Kurt. So it was an easy choice to adjust those. I also adjusted the counts of the dead killed in Dresden – we have more accurate data now than Kurt had then, and there’s nothing in Slaughterhouse-Five that makes sense with x people dead that doesn’t make sense with y<x people dead instead. I considered these aspects of it almost housekeeping: the sort of changes I’d expect to see in any adaptation of any media. The original already exists, and it’s not going anywhere! Anyway, everyone was on board with that from the start and I never had any pushback on it, which was gratifying.

KAPLAN: One of the very last pages of the Slaughterhouse-Five adaption is the Eliot Rosewater quote, “I think you just are going to have to come up with a lot of wonderful new lies, or people aren’t going to want to go on living.” Why was it important to include this quote at this point in the comic? Was this idea integral to your adaption of Slaughterhouse-Five?

NORTH: It was for a few reasons: one was that this line wasn’t in the comic part of the book, and it’s a great line that I didn’t want to see lost, so having it as a sort of post-book epigraph felt right. But you’re right in that it also is part of what the book’s about, about looking for a reason to keep going in the face of all this horror around us. I don’t see it as much as a capstone at the end as I do a sort of echo: a message from the boom coming back, just for a moment, when you’re at the end.

(Originally a different line there had been put in by the publisher and it was a line Eliot already said in the comic, and I was like, “no wait, I have the perfect line to go here and we won’t be repeating ourselves!” So it was in that sense a happy accident.)

KAPLAN: This question is at the behest of Beat writer Greg Silber: How would Billy Pilgrim escape if he got stuck in a hole while walking his dog?

NORTH: Hahaha, my true legacy: getting stuck in a hole with Noam Chompsky!!

When I was stuck I turned to Twitter, and with the help of an army of kind strangers, we managed to combine things in my inventory and get us both out of the hole, solving the puzzle. But Billy is not the sort of guy who takes the initiative like that, so I expect he would simply sit in the hole with his dog, enjoy the moment, perhaps travel in time to other such happy moments, and wait until his absence is noticed and one of his kids finds him – and then yells at him for just sitting in a hole when everyone else was out looking for him.

KAPLAN: When introducing characters in the Slaughterhouse-Five adaption, a specific 3-panel structure is repeatedly used, calling to mind the repetition of mantras that can be found through Vonnegut’s writing. What was the process of adapting Vonnegut’s unique prose into the medium of comics like? Was any aspect particularly easy or especially challenging?

NORTH: Haha, it was… all… challenging? I think? I didn’t want to be the person who messed up Vonnegut, and so that was something I kept in mind throughout. But the process went like this: I bought a large copy of the book, which I then reread and wrote all over: underlining lines, writing notes in the margin of how a scene could or should be adapted, marking ideas I had when reading it, stuff like that. I basically treated the prose as a sort of very rough draft for a comic, which the comics author had accidentally way overwritten and put into novel form, but the bones were still there.

One of the easiest parts was the Tralfamadorian book: that felt like it belonged as comics already, described as it is as short, urgent scenes, all collected together to form an image of life: that’s not too far from panels and a page of comics already, and when I reread that scene I knew what it would be right away. Some of the hardest parts were when Vonnegut told you almost the summary of what happened instead of the individual actions – that technique works like gangbusters in prose, letting you keep this incredible forward momentum, but it works less well in comics, and there are points where you want to hear the characters speak in their own words. So inventing that dialogue, which would read in Vonnegut’s voice and also fit into what was already in the book, and not sound like me at all – that was a tricky part. Honestly there’s been times when I was proofreading the book and I’d have to go back to the novel to find out which part I wrote and which part he did, which was great. (It was less to pat myself on the back and more to see what I’d be changing if I tweaked a line, I swear.) If I can fool myself, I think that counts as a success!

KAPLAN: Slaughterhouse-Five is a fragmented narrative, not only in terms of Billy Pilgrim’s personal story, but also in the way stories by Kilgore Trout – as well as the written material by Howard W. Campbell, Jr. and the nonfiction material demanded by Professor Rumfoord – are included directly in the novel. Why was it important to include these passages – often nearly word for word – in the comic adaption?

NORTH: Howard’s bit – where he talks about being poor and the way America blames her poor for their circumstances – resonates now probably even more than it did when it was written, and in comics – where pages are so rare and limited – it still felt like this sequence (and others like it) demanded that time and attention. Trout’s comics are fun and so emblematic of the book (both the comic and the prose novel) that it felt unnatural not to have them, like their absence would leave a big hole in the heart of the story. And Rumfoord’s books are really how you get to meet this character and the way he sees the world, so different than Billy. They all really justify themselves, which is of course not surprising, given that I was working off of Vonnegut’s story as a base: there’s not a lot in Slaughterhouse-Five that makes you say “hmm, yeah, this part is just filler, no need to worry about this!” I actually can’t think of any, which is part of why adapting it is so hard.

I imagine it would be much easier to convert a lesser story that I didn’t care about into comics than it is to convert a wonderful story that I and a fair chunk of the English-speaking world love. Whoops.

KAPLAN: In depicting the treatment of P.O.W.s and the fire-bombing of Dresden, did you draw on additional sources for research, or was the majority of the historical information used already contained in the source material?

NORTH: Like I mentioned before, some of the sources Vonnegut had access to at the time have been replaced by more accurate ones, so I double-checked all the hard data in the book – which sounds like a lot of work, but it wasn’t really. I was already doing as much research as I could finding photo reference for Albert – the book is a period piece, and while it takes 10 seconds to write “they’re in a WWII-era POW train”, it takes much longer to find out exactly what that looked like – and I felt like part of my job was to fill in as many blanks as I could. I didn’t get all of them, but Albert was amazing and tracked down some things I couldn’t, including likenesses for Kurt’s friends at the start of the book. He told me the Vonnegut estate themselves helped with that, which was just great.

KAPLAN: Why is it important to tell this World War II story now, in 2020? Why is it important for people in the United States to be familiar with Vonnegut’s story, ideas, and words?

NORTH: It’s kind of sad to admit that Vonnegut’s anti-war book written over 50 years ago is still relevant today, perhaps even more relevant today than it was initially. That doesn’t suggest that we’ve made a ton of progress as a species, and I’m sure Kurt himself, were he here, would say that he’d much prefer his book was forgotten as a relic of a different time than held up as an important and seminal work that’s as important today as the day it was written. But it is, and we all know more and more what conflict looks like, what war is and what it does to people.

It’s funny, back in January when the book was announced, I was doing an interview with Stars and Stripes – the US Military’s independent newspaper – and a reporter, calling me from Afghanistan, asked me about the book’s message, and nothing makes you feel like more of a jerk than telling a soldier that war is bad. Clearly it is, clearly he knows that more than I do and, fingers crossed, more than I ever will. So on some sense I feel profoundly underqualified to talk about this. But Vonnegut was there, in WWII, in Dresden, and Slaughterhouse-Five is him talking about it. I saw my job as bringing that message forward without distortion, knowing it’s still relevant, knowing that an anti-war book that’s still about opposing fascism and hatred and racism and Nazis no matter what still has a place here in 2020.