Two Dead

Written by Van Jensen

Illustrated by Nate Powell

Gallery 13

That America has a harsh history of race relations is not a mystery, nor that the concept of black and white citizens living in the same parts of town and working in the same places — to the degree that they do — is a pretty recent development in terms of being a norm. In Two Dead, writer Van Jensen takes these simple but deplorable aspects of American life as physical examples of the cultural chasms between us, drawing a direct line between the way things are now and the way things used to be, and specifically what has changed and what is the same as it ever was.

Jensen’s examination takes the form of a gritty crime story with a Touch of Evil vibe that portrays lawmen both crusading and corrupt, and also somewhere in between. World War II vet Gideon Kemp arrives in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1946, a new police hire by the mayor. Kemp has a very specific mission — to be the mayor’s eyes and ears in an effort to snuff out police corruption, with one target in particular. That’s chief of detectives Abraham Bailey, a fire and brimstone law enforcer who views the situation on the street as an all-out war of Old Testament proportion.

As Kemp begins to survey the situation, he finds the one gangster calls many of the shots in town, with a tight grip on local politicians. He also finds the segregation in the city to be contributing to corruption. A special unit of black police, who operate separately from the white police, are treated with contempt from both sides of the law and hit peak frustration with their lack of resources and compensation. The head of this unit, Jacob Davis, has a further problem — his brother Esau has procured well-paying work with the gangsters.

These sides intertwine even as they head for a collision with each other, while Kemp tries to keep it all from self-destructing. But he’s burdened by his own demons, overwhelming guilt born of a shooting during the war that drives much of his post-war actions, as well as difficulty in juggling work and home life. He’s straddled with a difficult partner, Bailey, who has a hair-trigger when it comes to violent retaliation against crime that Kemp has to keep under control, while also making clandestine reports to the mayor that slowly begin to tear at his conscience. And the bond he builds with Jacob, another World War II vet who saw the same horror but also faced racism from American troops that endangered American lives, is constantly challenged not only by the racial divide between them but also a dangerous situation that Kemp places Jacob in.

This is by the numbers crime noir, though. Jensen takes great care to let his themes play out in story and dialogue, but he also lets the characters seize some control of their own portrayals and not allow themselves to be figureheads for the themes. The result is that all points in this quadrilateral relationship end up being sympathetic, the path each has taken in some ways understandable. Even in the case of Bailey, whose pathological fury leads him to murder, there are aspects of his crusade and the guilt that fuels it that becomes undeniably human and enormously complex in his situation.

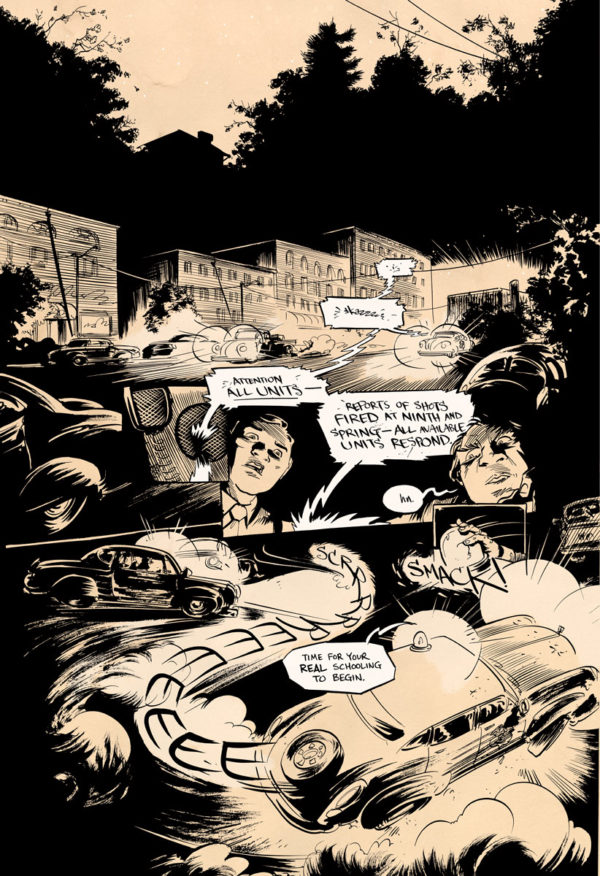

In bringing this all to life, Nate Powell outdoes himself. Powell’s always had a strong Eisner vibe, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it come through so strong as in Two Dead, and I think that has a lot to do with the Touch of Evil vibe I mentioned earlier. He turns the psychological state of the characters and the spiritual state of Little Rock into a vivid, dark setting for the characters to careen through. There’s a constant sense of unease, of the threat of the unknown, and a kinetic unpredictability to the action as Powell portrays it. It makes the terror and desperation that the characters feel and which fuels their actions seem palpable.

Two Dead stands mostly on the side of Jacob Davis, insisting that its white characters, even the noble Gideon Kemp, need to take a stand against their own if they want to set things on a correct course. At the same time, it doesn’t downplay the obstacles to someone like Kemp actually taking such an action, of the cultural behemoth he is up against and the instinctual protection of his own — meaning his wife and child — that can disrupt social justice. Complexity isn’t an excuse, but a horrible reality, and in a dark, dangerous world Two Dead suggests humanity may feel more at home in a horrible reality and it takes better than even the best of us to move past our nature.