They Called Us Enemy

Written by George Takei, Justin Eisenger, and Steven Scott

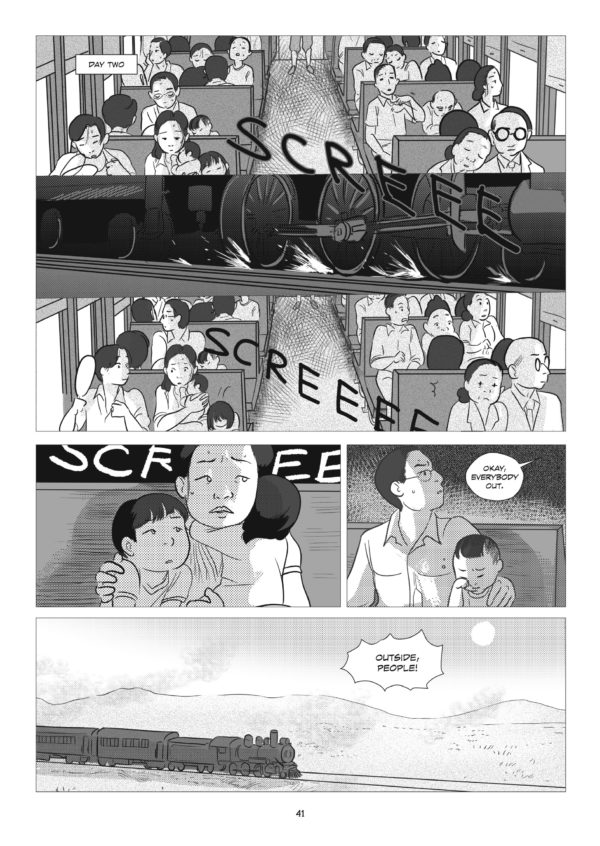

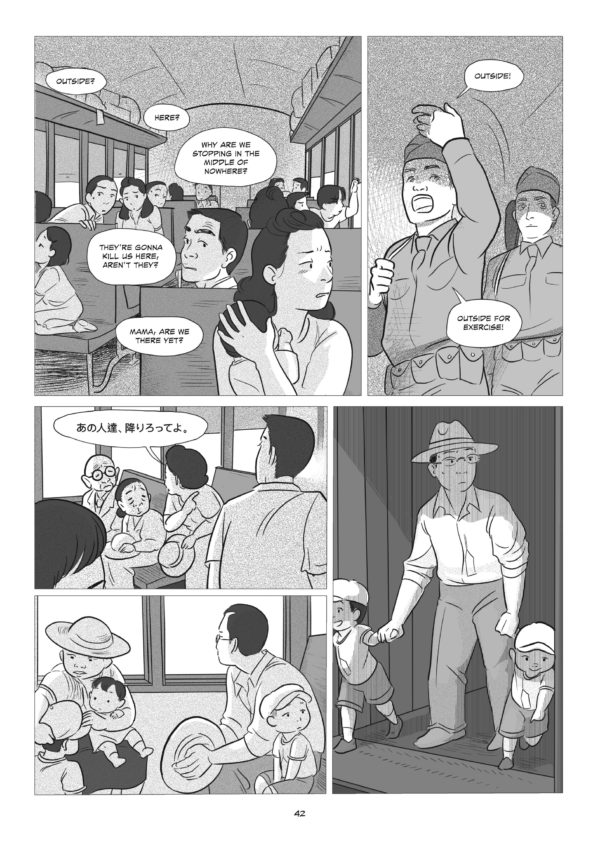

Illustrated by Harmony Becker

Top Shelf Productions

As too often happens in our country, it’s a current repeat of aspects of an earlier horror that spurs us into facing up to our own guilt in regard to what happened before. It’s not that the internment camps of the 1940s that imprisoned Japanese-Americans haven’t been acknowledged and discussed, it’s not that we haven’t acknowledged that our country did the wrong thing. It’s that we haven’t actually learned the lesson we needed to learn — a lesson we had already not learned when the 1940s rolled around.

George Takei’s new comic memoir, They Called Us Enemy, which covers his childhood in the camps and his adulthood coming to terms with his experience, hopes to help that lesson be digested more deeply. And it does so with a sense of urgency as Takei watches scores of undocumented immigrant children face the same terror as he did so long ago.

The Japanese American camps did not just happen out of nowhere. Prejudice against Japanese residents was already entrenched in American culture, particularly in California, merely exploding to an unprecedented level after Pearl Harbor was attacked. Part of what made it unprecedented was the official quality of it, with the U.S. government branding Japanese American families “suspected enemies” in order to freeze their assets and bank accounts, seizing property in home searches, rounding up and arresting community and religious leaders and making them disappear for years with a skill worthy of Iron Curtain nations.

California attorney general Earl Warren led the call to Japanese American detainment. The one person who could have stopped the racist wave, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, instead signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. Not even three months had passed since Pearl Harbor before the west coast was declared a military zone and Japanese American citizens were incarcerated by their own country.

As Takei points out, while Roosevelt’s executive order never specified Japanese people, the government of California were more direct, and soldiers rounded them up and took them away to camps, while also allowing the state to confiscate property, including farms, from the incarcerated people. These policies and many more were justified by public racist statements made by government officials.

Takei’s family — his father was a Japanese immigrant, but he and his mother were American-born, and his two siblings also — could not escape being swept up in this paranoid nightmare. And so one night soldiers showed up at the their door.

“Our childhoods continued to be made of grotesquely abnormal circumstances which would eventually become our ‘normal,’” is how Takei sums up the next four years of his life. Taken to live at the Santa Anita Racetrack horse stables and later grim camps in Arkansas and California, Takei relates a steady stream of degradation, born of paranoia and justified by racism.

In Takei’s experience, the Japanese American community, despite their treatment as victims of this American condition, rose above the expectations of their captors, generally creating communities behind the barbed wire. Takei documents numerous group efforts to help neighbors and improve the quality of life within these camps regardless of whether the government helped or not.

Leadership positions followed and Takei watched his father take on the role of block manager as part of a larger effort to create order within the imposed chaos and not allow their situation to dictate how they lived. It’s an admirable vision that also functions as a rebellion of sorts, particularly considering what they built could and would be torn apart by government-ordered relocations. People respond in kind to disrespect and neglectful treatment, though, and in some internment camps, the United States faced forceful resentment of its own creation, which further fractured the communities that had appeared and propelled shame across generations.

“Shame is a cruel thing,” says Takei. “It should rest on the perpetrators, but they don’t carry it the way victims do.”

And even when the ordeal was over, the population was shoved back into the world with no consideration, no help, some deported, some left to precarious circumstances and displacement in America — not to mention good, old-fashioned, everyday American racism. Like baseball and apple pie, you might say.

With all the heaviness inherent in Takei’s story, lightening the emotional load of the presentation doesn’t come easy. Takei doesn’t shy away from happier moments, even amusing moments, but the circumstances in which they happen taint them from being true releases. Harmony Becker does a huge amount of the heavy-lifting in keeping They Called Us Enemy from becoming too emotionally oppressive. Her work is in a Manga-style and keeps the darkness at bay even as it clearly depicts such negative events. In many ways, she is the perfect compliment to Takei’s soul, visualizing his overriding emotions to his own experience.

And it is Takei’s soul that is the star of They Called Us Enemy, especially in its representation of the souls of so many others. If there is any power to America, anything truly admirable, it’s that despite the treatment doled out to people considered “the other,” most of them choose to remain peaceful, to remain in the country, and to work to make it more fair and welcoming despite how they’ve been treated. Not to assimilate without question to what is wrong, but help shift the country into a better place. That’s pretty amazing. People who are shit upon typically see potential and recognize their own role in making the country reach it, despite the harangue of righteous oppressors that never seems to go away.

Takei doesn’t explore the ideas historically — that is, he doesn’t trace a history of American mass detention prior to World War II — but he does lay out the connection between what he endured and what is going on now with undocumented immigrants, and he he doesn’t try to soft sell it. He presents it as a horror that we ought to be ashamed of. And he’s right. We should know better by now. Such actions do no good and it’s no longer acceptable to intentionally obfuscate from ourselves the nightmares we are currently creating for others by lashing out at them about our own insecurities. And as Takei reminds us, we each play a role in the dehumanization of others, so we should also do our part in striking that from the American character.