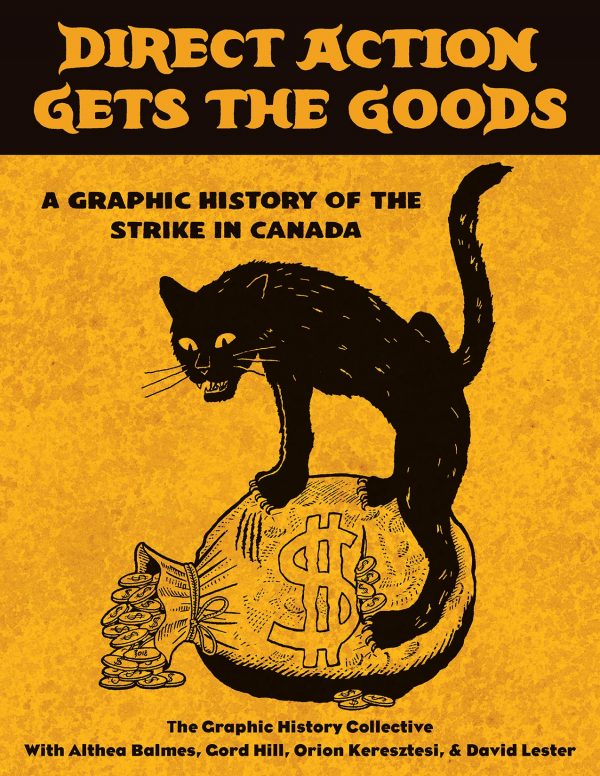

Direct Action Gets The Goods

by The Graphic History Collective with Althea Balmes, Gord Hill, Orion Keresztesi

Between the Lines

A history of strikes in Canada is possibly niche territory, but it never hurts to get an overview of radical action in these dire times. As those who benefit from the power structures have ramped up their attempts to limit dissent in so many ways, it’s been encouraging to see protest and even civil disobedience become more a part of everyday life and more inclusive of ordinary people. Striking still happens, but it also comes with a stigma, and this book operates as a good tool to help get past that.

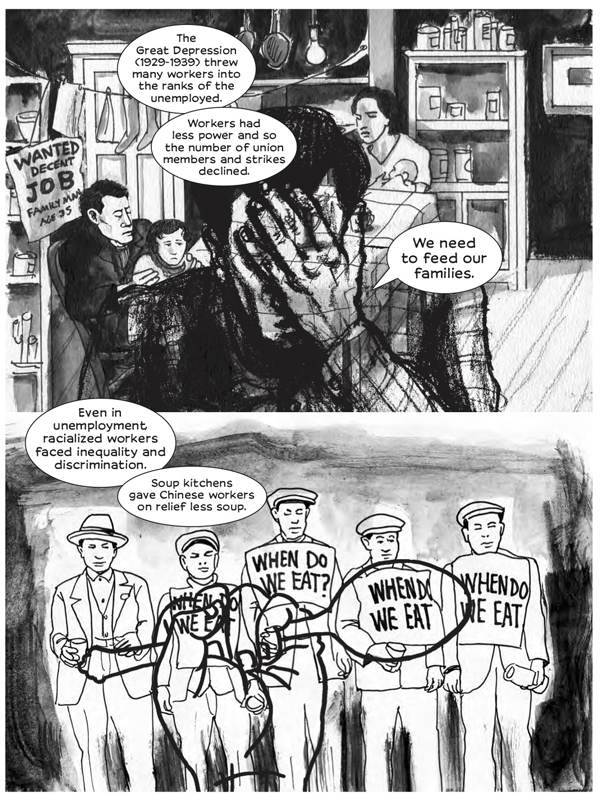

Rounding up the circumstances and goals of strikes in Canada from as far back as 1800, Direct Action Gets The Goods presents these not as aberrations in social order but part of the continuum of history, where workers routinely utilize the strike format in order to not only demand rights that aren’t being met, but also keeping power in check. Besides meticulously laying out a history that’s the book’s real accomplishment, and the sequential format helps it unfold smoothly.

The cartooning is often charming, and David Lester’s work covering the 1900s to the 1940s is particularly interesting, evoking the times with a ghostly illustration style that incorporates elements of collage to express the swirl of ideas, passion, and activity it portrays.

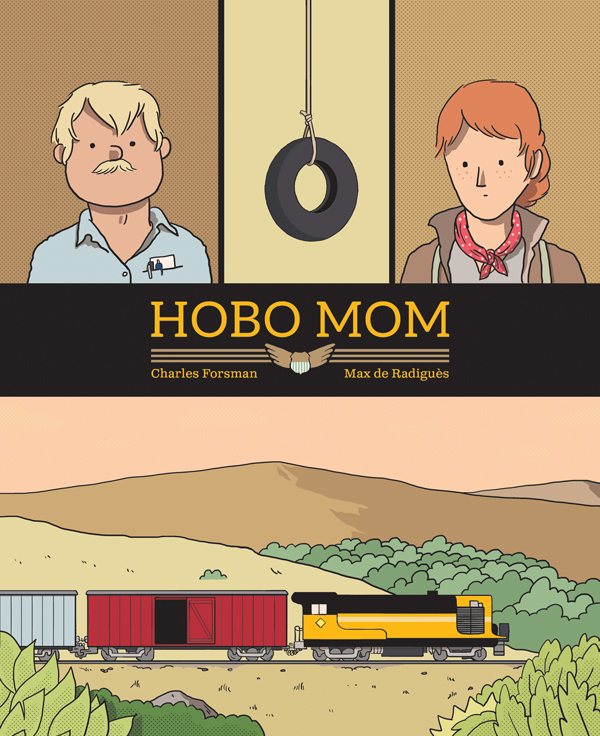

Hobo Mom by Charles Forsman and Max de Radiguès

Fantagraphics Book

I hadn’t really considered how much Forsman and de Radiguès shared styles and sensibilities until Hobo Mom appeared, but unlike so many collaborations, this doesn’t appear to at all involve two people, but rather one person created from a joining of the two cartoonists. That’s an accomplishment in itself, to create something so seamless, but it also manages to do so without adding any awkward bumps to either’s output.

It’s a spare tale of a woman returning home to her husband and child after taking off years ago and, apparently, taking to the rails. It’s an awkward homecoming, and the husband has to grapple with his feelings of abandonment and his desires while trying to protect his daughter from the potential devastation of learning this woman is her mother and the possibility of second flight.

Forsman and de Radiguès let this drama unfold quietly and somberly, with plenty of foreboding. We want to believe the mother had valid reasons, we want to believe she won’t repeat her mistakes, we want to believe she’ll get help. But dysfunction and hurt are the territories both cartoonists typically wander in, especially the inevitability of the actions of broken people. This is a beautiful work that might hurt you.

Viewotron #1

by Sam Sharpe and Peach S. Goodrich

Adhouse Books

The title Viewotron refers to a prop in a science fiction movie featured in the first story by both creators, “The Secret Origin of the Viewotron,” which centers around an object that has great fictional significance but what that is exactly is unclear. In other words, it’s a neat idea, but only half-formed.

A similar idea is addressed in the one-pager that precedes it, “The Golden Ring of Titans,” also by both creators, in which the Younonome of the distant planet of Titans build their entire existence around a myth of the universe and it has become so ingrained to the purpose and structure of their lives that they can’t acknowledge any debunking it. Both these stories stand as observant fables of how the human brain works and how our lives are probably structured around things we don’t understand in any complete form. But funny.

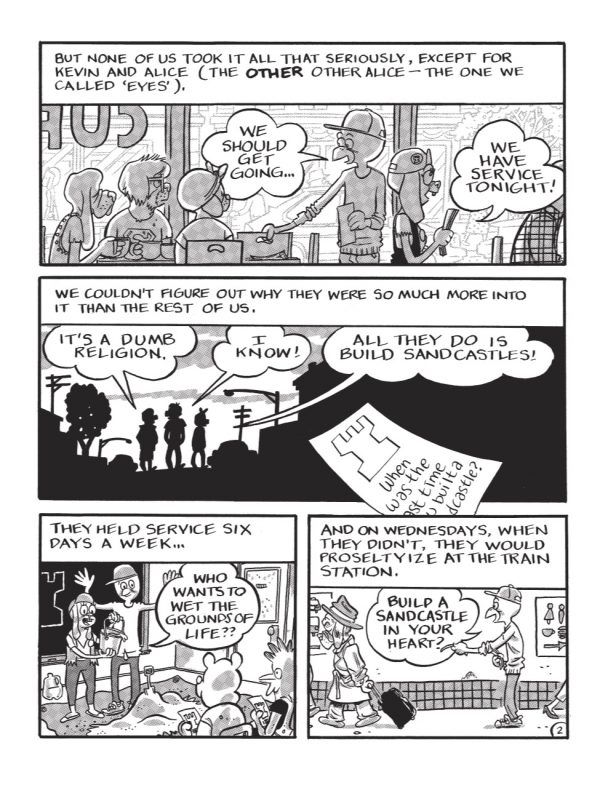

Sharpe’s “That First Summer After College We All Stayed in the City and Founded Religions …” is about exactly what the title says it’s about, but it’s also about the transference of beliefs and how an obvious fiction can be accepted as truth if introduced in the right way — even if the person accepting it as a truth watched it born as a fiction. Even with such headiness, it’s a funny, matter-of-fact narrative about what people do on the cusp of adulthood, and then how those activities can come to bite you on the ass eventually.

Other stories take the same tactic, transforming philosophical ideas about beliefs and relationships and self-perception and responsibility, and other human conditions, into extremely amusing, very personable comics. Sharpe and Goodrich variously trade-off and partner, creating a nice diversity that features slices of life coupled with absurd parables, sometimes within the same story, actually exemplified by the book’s one-page closer, Sharp’s “Stress Relief,” which captures the universal cycle of stress succinctly and perfectly or Goodrich’s “Bertrand is … aloof” which demonstrates the opposite reaction to what reality lobs at us.

And then there’s the simple, silly, brilliant hilarity of Sharpe’s “Who Will Name the Boy Bands?” which might be the best thing ever.