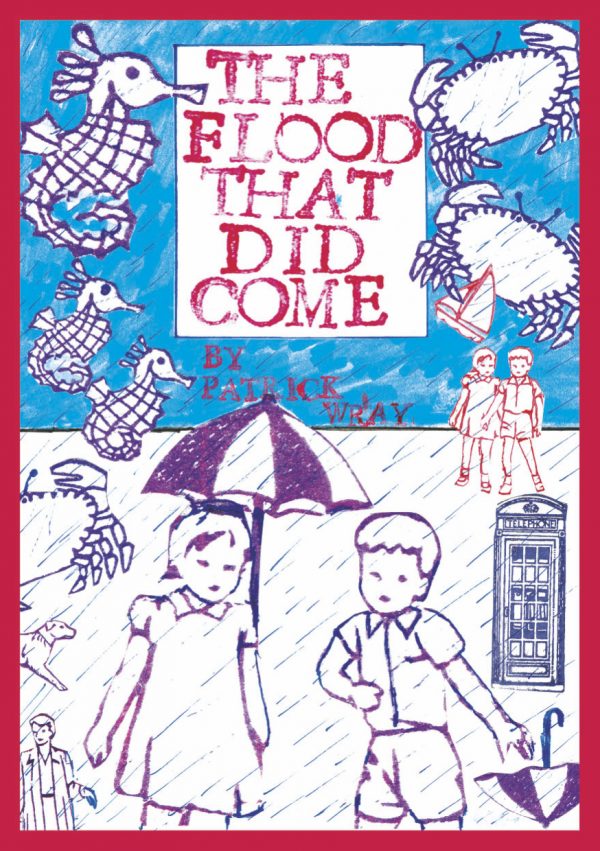

The Flood That Did Come

By Patrick Wray

Avery Hill

In the ongoing quest to allow your brain to qualify a new thing you encounter by matching it up in some way with an old thing you are already well acquainted with, Patrick Wray’s The Flood That Did Come has proved noticeably challenging for me. Not that I need to make that qualification in order to enjoy something, but I do find it helpful in preparing to review a work, partly in order to establish a creative line through time that reveals movement forward, evolution, and innovation, and also to reveal that line to be alive and thriving. Doing this gives me clarity in examining the process of creating works within the creative line.

Damned if I can place The Flood That Did Come along any line. I have a few possibilities, but they are mostly linked by my inability to place them within any creative line, coupled with their dense saturation of Britishness. In other words, they are only placed there in my mind because they are British works that don’t fit in anywhere else. If they were people at a party, they might just stare at each other awkwardly and then go back to reading their books.

One of those is the works of Glenn Baxter. Another is the online project of Scarfolk. Still another is the Famous Five parody that appeared on the old Comic Strip Presents, the Five Go Mad episodes, featuring Jennifer Saunders, Dawn French, Adrian Edmondson, and others. Throw Frank Sidebottom in there while we’re at it. Patrick Wray’s graphic novel fits in snugly with that company.

In terms of basic plot, The Flood That Did Come is very simple. It’s the year 2036 — I don’t know that this is actually important to the story, but Wray does — and torrential rains have brought about devastating floods to Kingsby County. The Village of Pennyworth is doing much better than the other villages and because of this neighboring village, Brook Falls, has hatched a plan to usurp Pennyworth and make it their own. Not only that, but Brook Falls says that it has a historical right to do so.

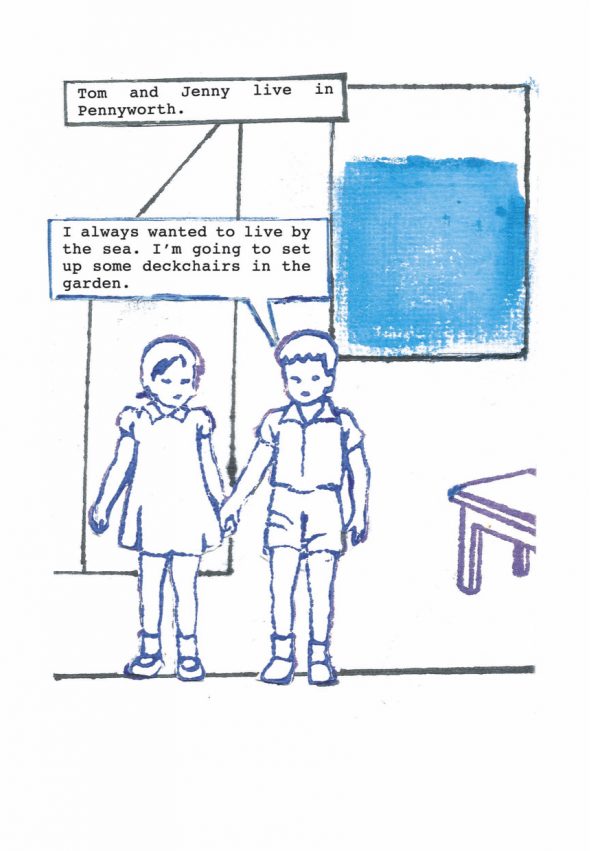

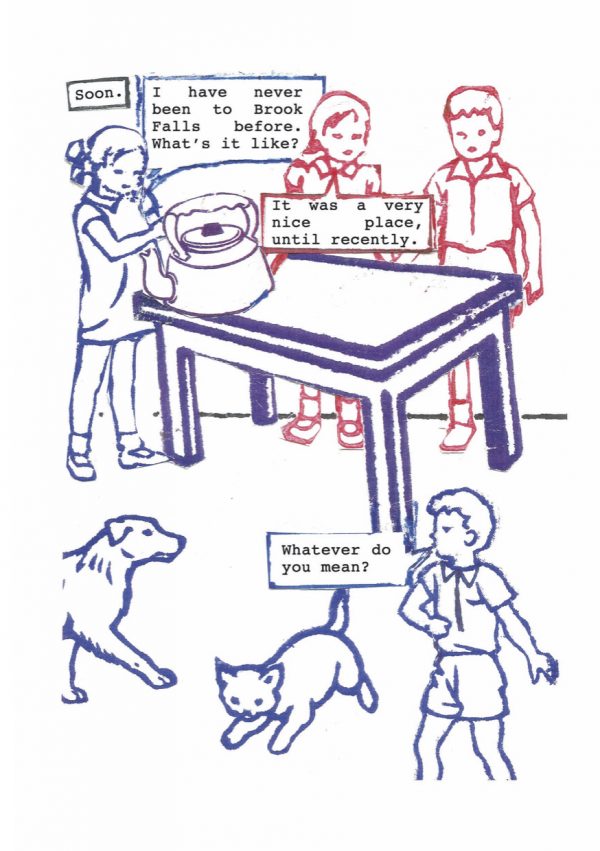

Wray at first introduces us to his Pennyworth protagonists, Tom and Jenny, who do the work of explaining the situation in their formal school primer book form of conversation. While surveying the effects of the flooding in their own town, Tom and Jenny meet the nearly identical Jim and Charlotte from Brook Fall who, after niceties, exhibit the same primer school conversational talents as Tom and Jenny in explaining the situation in their own home village. As the situation escalates and Pennyworth has to confront the first wave from Brook Fall, the action unfolds with the same awkward pacing as the sentences out of Tom and Jenny’s mouths.

Wray matches the verbal portion of the book with a visual style that not only represents the passionless lingual abilities of its characters but magnifies them. Tom, Jenny, Jim, and Charlotte are mostly red and blue figures that appear as if they were stamped on the page, and within their word balloons is sterile typewriting rather than evocative typeface or personable hand lettering.

When other characters appear, they have the same stamped quality as the children, which also feels like clip art. Objects like buildings or cars or boats are flat silhouettes focused more on the geometry of their presentation than the reality of the representation.

All in all, it’s a peculiar book with a peculiar presentation, which obviously makes it stand out from just about anything being released these days and which is certainly its major charm. And somehow it all feels entirely apt, particularly since the plot of the book is about a disaster that upends the established order of life. Obviously Wray conceived and created the book well before COVID was a thing, but somehow the timing of its release is perfect. As the pandemic has in many ways boiled us down to our essence and flatly revealed the selfishness and lack of empathy that many of us keep hidden in our usual three-dimensional presentations, so The Flood That Did Come melts away the things that distinguish humans from one another and lets the disarming threads between communities — that is, the natural way in which we stomp all over others in order to survive and expect them to just accept that — exist in plain sight of the reader.

This is perhaps a cynical view, but as the pandemic has revealed, cynicism is probably the natural order of things anyhow. It’s the upbeat dreamers who never had a clue. And as the country crumbles around us with mounting calamities and civil unrest, the essence of each of us might just be a Tom or a Jenny or a Jim or a Charlotte, drily explaining the situation and only offering solutions that bring maximum parodic whimsy to the situation rather than actually doing anything.