The offices of Avery Hill Publishing are located in London, and that seems about right to me, given the Britishness of so many of its titles. Thinking in terms of bands, Avery Hill definitely seems like the XTC of comics publishers, and like that band, the state of being known as “Britishness” winds through every offering. Something about its titles are entrenched in their country of publishing origin, even though some of the creators live beyond its borders.

If Avery Hill were one person it would be eccentric but reserved, charming in their oddness, filled with unusual originality but never the type to scream loudly about that, instead presenting itself to the world with dignity and allowing the world to discover what lurks inside, if the world so chooses.

I guess these are British cultural cliches, but sometimes cliches stem from the truth, and I did mention XTC, didn’t I? There are plenty of others of lesser renown that fit — Martin Newell, say, or The Monochrome Set, or, to get really obscure, Virginia Astley — but these characteristics are there, and they almost always accompany something extremely interesting.

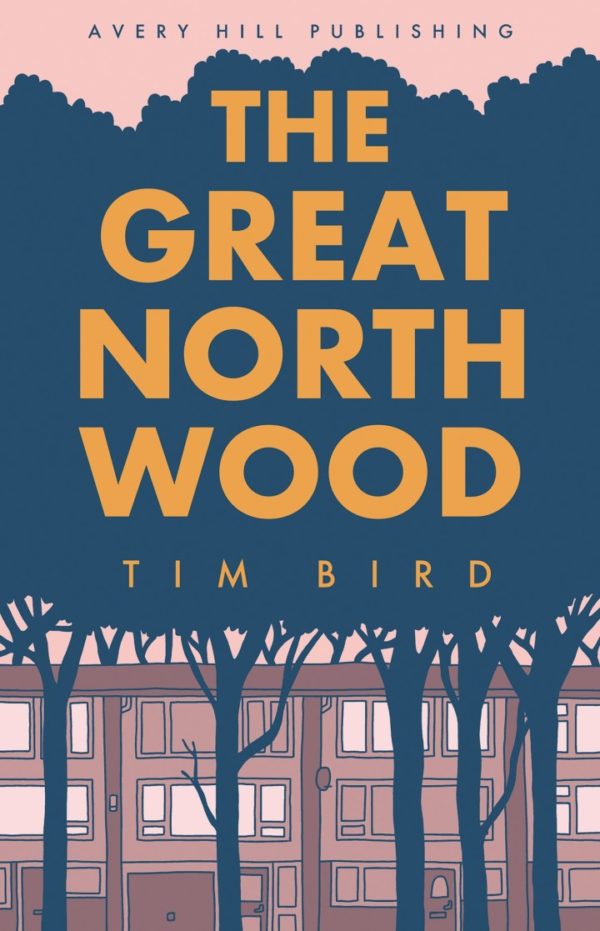

And any company that publishes something like Tim Bird’s The Great North Wood, a gentle comic entirely about the history of a forest stretching from Croydon to Deptford, is definitely flying its Britishness Flag high. Lizzy Stewart’s recent Walking Distance, which documents time spent wandering around London, doesn’t dissuade me from this feeling.

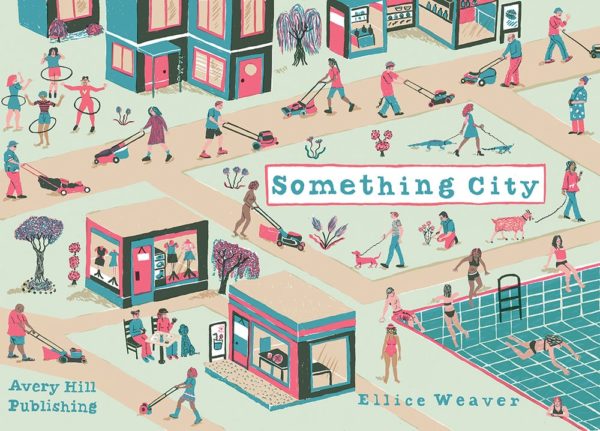

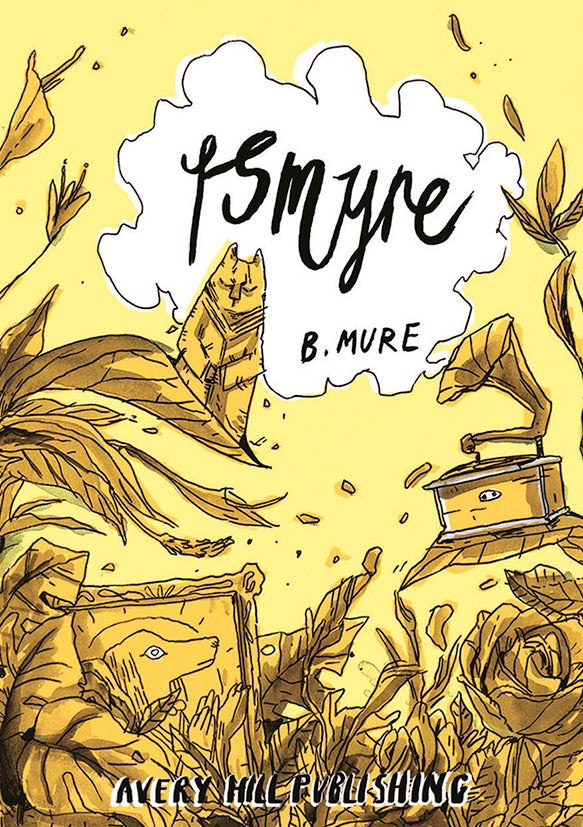

Not that all their titles are literal in this Britishness I detect, but that flavor manifests in so many titles in the Avery Hill catalog — all the whimsical fantasy Ismyre books of B. Mure, Claire Scully’s manifestation of a psychological landscape in Desolation Wilderness, Alex Potts’ foreboding story about isolated European communities in It’s Cold in the River at Night, Ellice Weaver’s sly and absurd account of the imaginary Something City, George Wylesol‘s eccentric Internet Crusader, and plenty of others.

And like so much British music — XTC, of course, Squeeze, The Clash, The Libertines, hell, why not the Beatles, and so many others — Avery Hill’s story starts with a close bond between two lads. In this case it’s Ricky Miller and Dave White, who’ve known each other since age 11, when they went to school together.

“As you do at school you start getting into certain groups and finding out you’ve got overlap in interests and stuff,” White said.

“We vaguely knew each other when we were 11, but I guess it was more when we were like 15, 16, that we used to walk home the same way,” Miller expanded. “We were both into comics at that time and both probably discovering music and things. So I guess that’s where it started. We would talk about comics on the way home., mainly the Marvel superhero stuff.”

This was the early-to-mid ‘90s. The two used to live in proximity to the same comic shop, about 10 minutes away from each other’s house, and they especially bonded over the X-Men. But they were looking to grow, and it was Cerebus that soon captured their attention.

“We thought we were extremely intellectual and mature to be reading Cerebus,” White said, “but just finding copies was hard enough actually. And it just kind of went from there.”

Where it went to was music

“We were both into the Brit Pop stuff that was going on with that time,” Miller said. “We were in with the same group and people used to go to clubs and gigs and things like that.”

“Once we started getting into music and going out and spending our time in ill-gotten ways, I personally and I think probably the same for Ricky as well, we fell out of love with comics for a while because it was just hard to find the good stuff,” White explained.

They had encountered other indie comics after Cerebus, but it just wasn’t enough to keep them reading. Besides, Brit Pop demanded their attention and, as Miller pointed out, once they were in university, they just didn’t have the expendable pocket money that they once had. And so they moved onto other projects together, including a band, The Do-Nothing Kings, which White says “was probably not as short-lived as it should have been” but which fits in rather well with what I was saying before about British bands. There was also a music blog that kept them occupied for a while.

But then, about 10 years later, White decided to pop into a Forbidden Planet, where he picked up a copy of Marvel’s Civil War comic. That reignited his interest and he started filling in the gap of what he had missed. It wasn’t an entirely smooth transition back though. Miller needed some proof.

“Dave would tell me about it and I would laugh at him for reading comics as an adult,” Miller said. “And then he lent me the first two trades of Y the Last Man and the first trade of Fables and that got me right back into it.”

It got them doing more than reading comics. First they chucked the music blog and started an anthology zine called Tiny Dancing that was filled with prose, illustration, poetry, and comics. The pair wanted to do something that they could hold in their hands. As Tiny

They were able to get some issues into comics shop, and an issue was picked up by Tim Bird, who immediately wrote to pitch a comic, and scores of other interesting cartoonists began to enter the picture. The duo shifted their efforts to an anthology called Reads — get the Cerebus reference? — and somewhere between the first and second volume, Avery Hill had become a real thing.

“We decided that that was the time to take a bit of a step forward,” Miller said, “and then we put a bit more money into the company, still not very much, it was just our own money, and we launched I think four books at the same time.”

The first two books as Avery Hill were Days, a collection by Simon Moreton, and The Beginner’s Guide to Being Outside by Gill Hatcher, but neither of those were sprung from or even led to what White and Miller would qualify as a cohesive business plan.

“We just roll with it and adapt really, which has kind of been the case since the beginning and still is,” said Miller. “If it’s a project we want to do, then we say we’ll do it and we figure out how we’re going to do it after that. I mean, neither of us have ever had any kind of publishing background or comics background or arts background really so we were making it up as we were going along.”

The two divided up the company responsibilities based on what they liked to do and what they were good at. Miller covered much of the business side, while White naturally drifted to the production and printing. As time went along, if they recognized any deficiencies in their own abilities they found a person who was much better at whatever it was which has expanded the team, adding Steve Walsh as Head of Sales and Katriona Chapman as Head of Marketing, as well as Sarah Wray to handle further marketing.

One thing that hasn’t changed since the beginning, though, is their pledge to not allow the business of publishing take over the act of choosing to publish.

“I think it’s fair to say that if we couldn’t find a project that we’re interested in for a period of time, we wouldn’t put anything out,” White said. “It’s not that we are committed to a certain number of books a year or a certain number of creators a year, it’s more finding the right projects.”

“We generally say that Avery Hill was like the cross section of our tastes,” Miller said. “We’re both into quite different things but then also there’s a lot of crossover, which is why we were friends in the first place. When we were growing up, there’d be some music Dave would like that I would hate and some stuff I’d like that he would hate. Where we crossed over, we were probably pretty sure that stuff was actually good. I think it’s the same here. We both bring in slightly different taste to it, but where we both like something, I think we’re generally pretty confident that that one’s going to be a good one.”

“We do struggle to describe it beyond the fact that it’s stuff that we like and we’d buy if it was on the shelf and someone else had published it,” White said.

So basically, an Avery Hill book is the one that sits in the middle of the Venn Diagram charting White and Miller’s tastes. But sometimes, projects don’t even make it to that point. MIller recalls a recent one that was suggested to them that they agreed was great work and would be a sure commercial success, but somehow, it just didn’t feel right for Avery Hill. It didn’t mean anything to them personally, and since they both have day jobs, they are not reliant on Avery Hill for their income. They have to love it to publish it.

“I think if we were working to figure that out, like a proper business, we probably would have more of an idea of what an Avery Hill book would be,” Miller said, “and go, okay,

They both said that they are happy to have readers and reviewers work out for themselves what constitutes an Avery Hill book. If someone were to ask me, I would mention narratives with an experimental edge and a quiet presentation. I would mention that they often have a contemplative demeanor that accesses darkness. I would mention visual styles that embrace illustration as much as they do cartooning, if not more than. And of course, I would mention the Britishness.

One area that the company has especially excelled in is publishing work by women creators. Over 50% of Avery Hill titles are by women, which the publishers claim wasn’t by design, but simply a reflection of the atmosphere in comics.

“I honestly don’t understand how, especially in the UK and US markets and every publisher isn’t doing this because it’s just very easy to find very, very talented female creators,” Miller said. “They’re just everywhere. We just see them every con we go to. And especially if you look at some of the great, a female American creators of the moment. They’re generally the best around.”

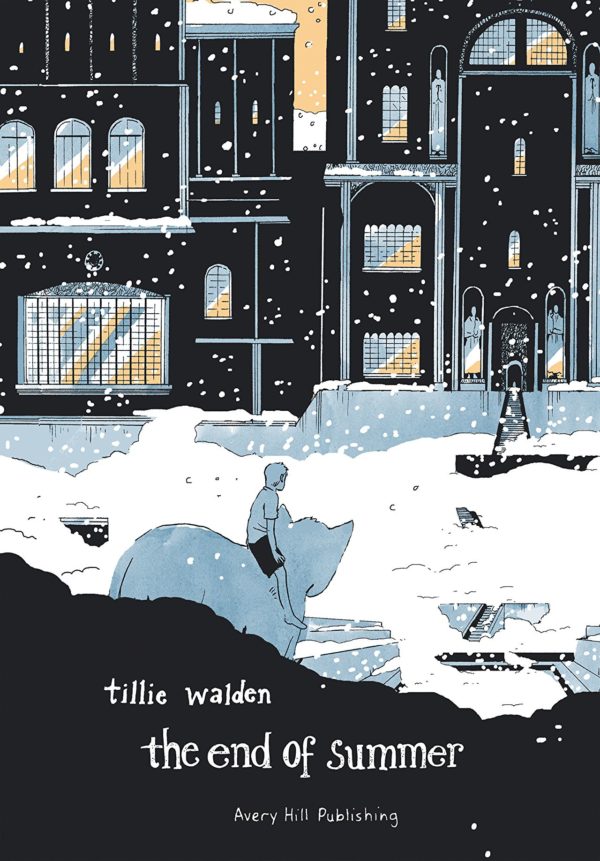

Tillie Walden has been one of the biggest success stories to come out of Avery Hill, starting with her acclaimed debut, The End of Summer. Walden was nominated for an Eisner and won an Ignatz and her most recent book, On A Sunbeam, which was published in America by First Second, won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

The publishing team found Walden online and contacted her out of the blue about publishing a book of her work. At that point she was 17 and finishing high school, so they decided to check back with her in 6 months, by which time she was attending the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont. Originally, her book was going to be a collection of her web comics until Walden proposed a 100-page graphic novel instead.

“I was like, well you’re only 18, you just started school, you probably shouldn’t do a 100 page graphic novel as your first book,” Miller said. “And then she sent me a one page treatment of, and me and Dave looked at it and we were like, yeah, we’ll do that. That’s good.”

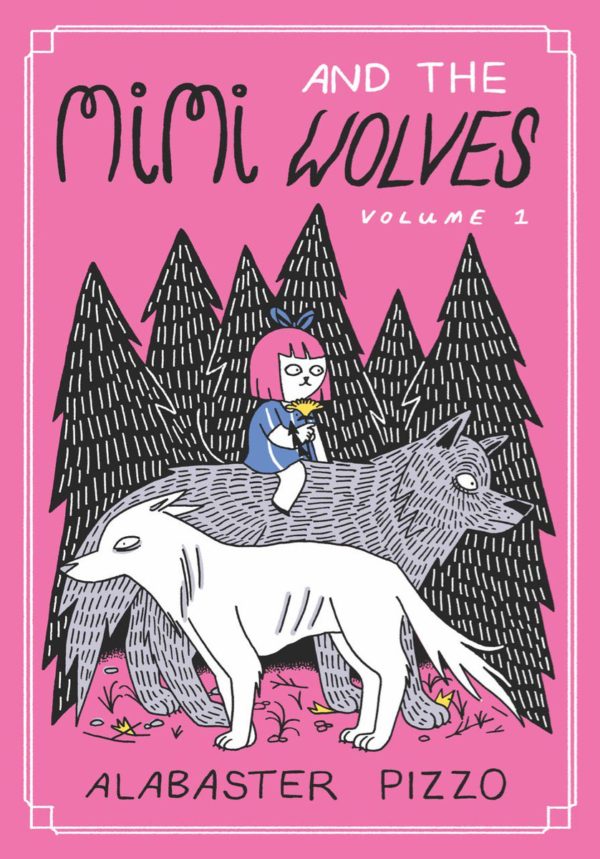

The more recent acquisition of Alabaster Pizzo’s Mimi and the Wolves, which comes out in November, shows that not much has changed in their methodology since publishing Walden.

“I’ve been pestering Alabaster for about three or four years and to try and do Mimi,” Miller said. ”I read the first issue and it just absolutely blew me away. I met her at a couple of cons and would email her every so often saying, oh, are you ready to do a book of Mimi yet? Eventually she gave in and said we could. I assumed every publisher was knocking on her door for this book. And I don’t think they were, but I think that can only be because they just hadn’t heard of it because it’s an amazing book.”

Avery Hill projects are initiated by one of the two publishers. They get submissions, they said, but they can’t recall a single one that they’ve moved forward with. They find what they love and then they let the creators know that they love it.

“It’s a case of us approaching them exactly as Ricky described with Tillie,” said White, “to say, we love your work and if there’s anything you think we could help you out with let us know and we’ll start talking about ideas and whether it’s something that we can actually contribute to.”

A sure sign of their success, they say, is that their dream list of creators they want to work with is getting longer and longer, but the possibilities of them actually being able to work with many of them is getting surer and surer, and they’ve been fortunate enough to be able to cross some off the list as well. The philosophy behind this success has been to offer creative freedom and to trust the people doing the comics to live up to the confidence they’ve place in their talents.

It appears they have a knack for comics publishing — definitely more than they did the band or the music blog. So what exactly is so different about Avery Hill that it qualifies as the secret of their success?

“All the others were a lot easier just to stop doing,” explained Miller. “We still haven’t quite figured out how you stop being a publishing company and that’s probably why we’re still doing this one.”

Comments are closed.