Walking Distance

By Lizzy Stewart

Avery Hill

“But then how do you live?” asks Lizzy Stewart part way through Walking Distance following a compilation of circumstances that make the world seem unlivable, and following a summation of the distress that she feels about whether the methods of shaming that have been chosen to solve the problem of an unlivable world are the right methods. The question itself, though is a fair question that could be posed to anyone, in almost any circumstance, against the backdrop of whatever ills they are pummeled, whatever poisons they absorb, whatever ways their unsureness disarms their ability to be happy or even functional.

But it’s also a fair question to people who just get on with things despite all that other stuff. How do they do it? Really — how?

It’s a question we’d all love the answer to. I’m afraid I share Stewart’s answer, the necessary action of not looking directly at the overwhelming problems of the world, but trying to acknowledge them because, as she says, it’s the least anyone can do amidst our self-preservation. But when she characterizes world events as “a crow trapped in your house … panicked and screeching,” she well illustrates what some of us grapple with.

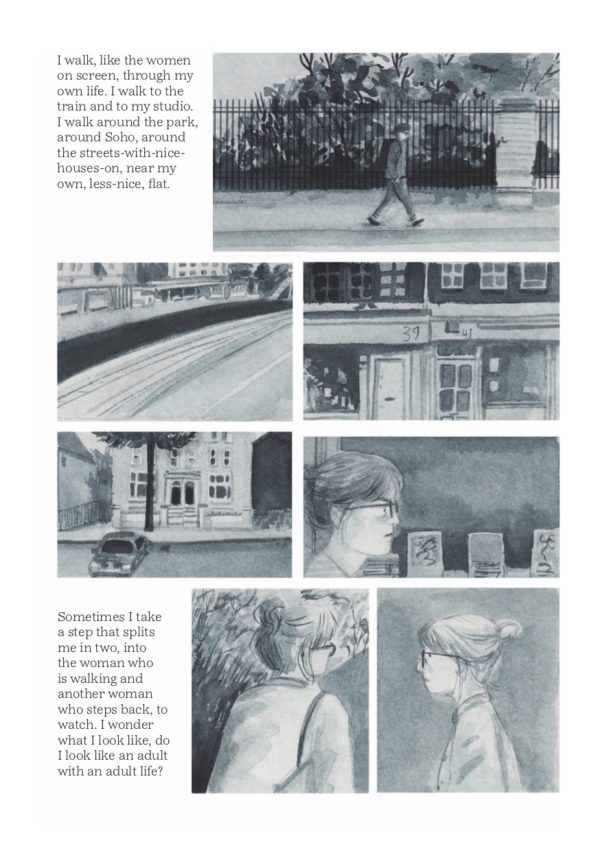

Walking Distance is not about being trapped in that house with that crow, though. It’s about being free of that house and that crow and confronting that situation on your own terms. It’s about walking specifically, and Stewart uses a prose and illustration format to investigate her relationship with that action within the London area.

Stewart’s art serves multiple purposes — capturing her in the act of walking, depicting the places where she walks, for instance. It also gives her the opportunity to present her ideals of women walking. The art offers multiple points of entry to the action and setting, while the words bring forth the journey that’s happening inside, a raking over of her own life and choices in context of the way society makes them. How does she stack up? “But how do you live?”

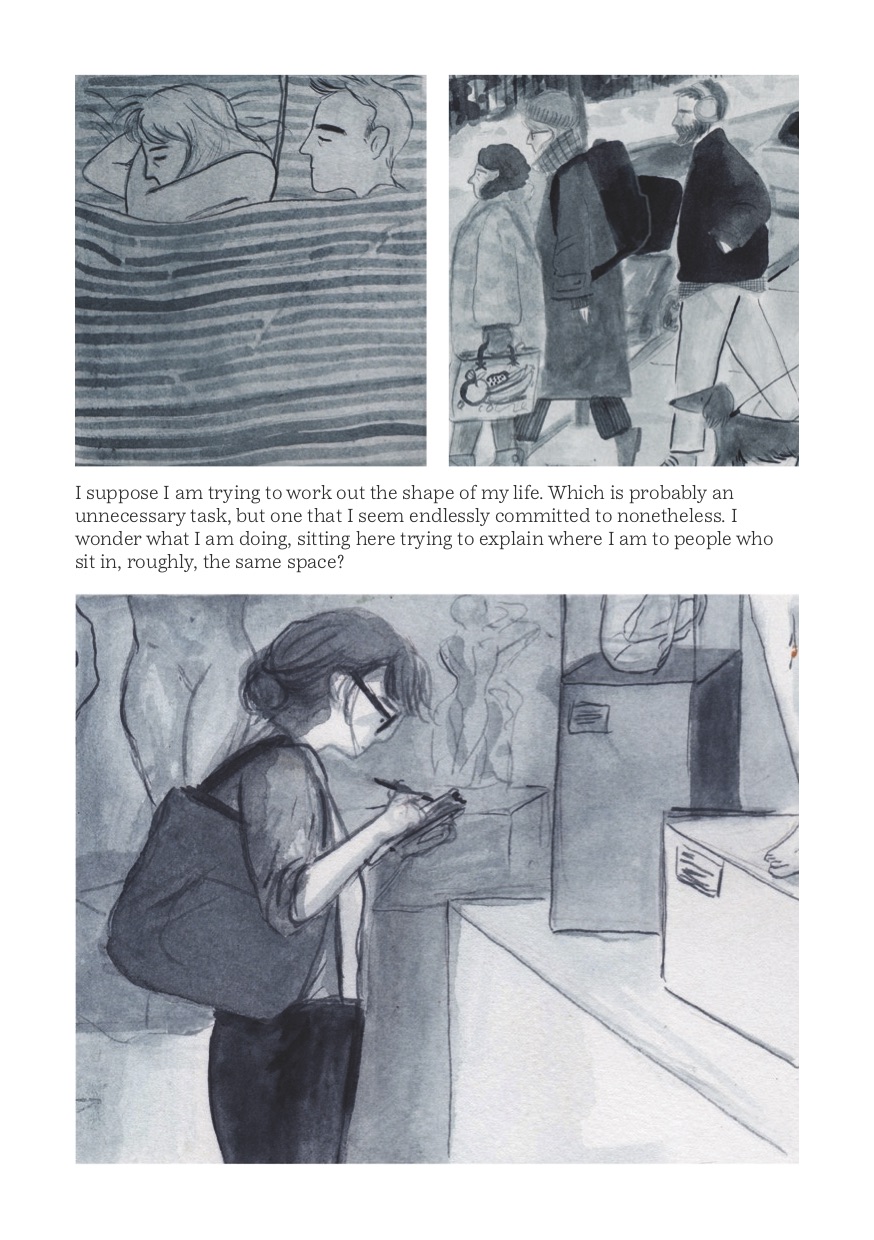

Having entered her 30s, Stewart is at that age of reckoning where you pour over the details of all the things you’ve been doing without much care for the past decade. Did you make the right decisions? Did you actually think about the decisions or did you just let them happen for you? Are you prepared for the person you are going to become, or are you just going to let that happen, too? When you are out walking, do you have a plan? Or are you just wandering? Is that the way you live?

Stewart rightfully expresses a concern that by looking inward too much, the self becomes an obstruction to the wider world, though that doesn’t seem to be what is happening here, especially given her addendum that fleshes out some of her poetic depictions of women walking in films with the real life fear a woman walking on the street alone can feel.

In the same addendum, she also acknowledges that by the time her work sees print, she may have moved on from the thoughts she expressed in it. And she may find herself saddled to what others say this book is about. And her views of the state of the world and anyone’s struggle to retain their mental health within it might miss the point that to save the world, mental health might be the necessary sacrifice.

I appreciate Stewart opening up her brain in Walking Distance in the way she does. If anything, it makes me feel less alone in the world. There is something about encountering people you don’t know saying things that make sense to you during a time when so little makes so little of it. It’s a distressed meditation, a meditation that second guesses itself, but that’s what makes it a worthy and very human meditation that felt less like reading a book and more like being with a person.

Comments are closed.