As a meditation on man’s relationship with nature and the landscape, and the poetic ironies inherent in this relationship, The Great North Wood presents one powerful image that sticks with you as histories unfold — an empty box of fried chicken, discarded on the ground, with a picture of a chicken on it. That’s a metaphor for just about everything Tim Bird is about to present — a modern creation that uses an aspect of nature as sustenance while replacing the actual bird with a tribute to mark its relevance. A picture on a manufactured box is all that is left of the bird that once walked the earth. A logo that looms in consumer’s heads, as recognizable as the bird it borrows its image from.

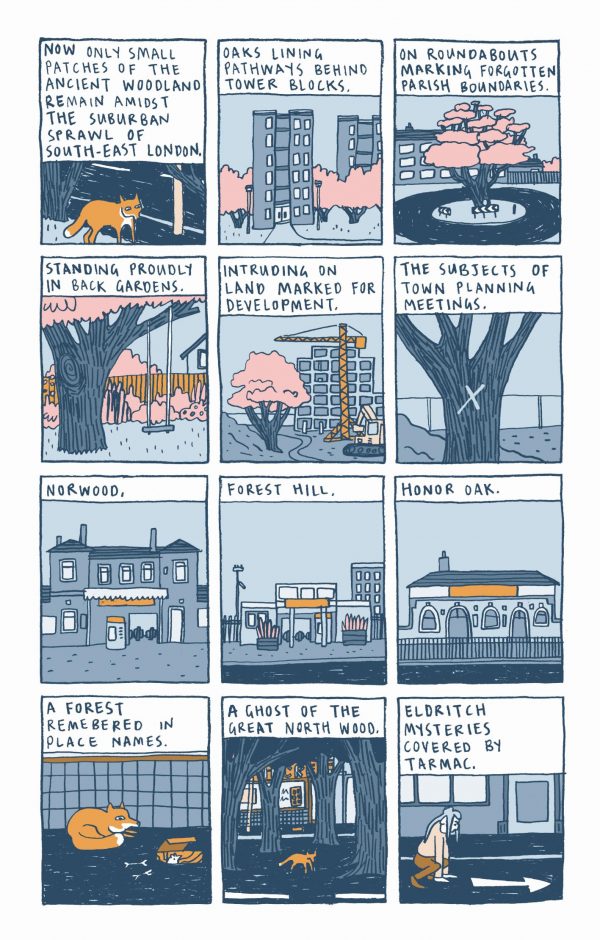

In Bird’s telling, the landscape is living history, but the aspects that might tell you the most about are inconspicuous within the clutter. A tree that seems like a tree, like any old tree that you might see at a multi-road junction during your mundane daily wandering could be one that Queen Elizabeth I is said to have drunkenly knighted. Or it may be a marker for something else, the boundaries between parishes. And before it was any of these, it was one of thousands that lived on the landscape before humans seized control and used trees to build their own structures, as well as the vehicles by which they could take to the ocean and leave the landscape behind.

Or it may be a fraud of sorts. A tree to replace the legendary tree, one that hasn’t seen hundreds and hundreds of years, but one century and that’s all. And it’s just the name of the tree, the Honor Oak, that still exists. The new tree is just a marker the tree that came before it. A symbol of a longer history.

When is a tree more than just a tree? When you know what that tree has seen. But even when you don’t, there are probably stories that have been attached to it. Any given tree is a magnet for legends concocted to explain why we humans and what we have built in the world are special.

It’s those legends that fill the landscape as much as our roads, our structures, and they represent points of contact between man and nature when nature becomes home and hiding place to those who reject civilization but are undeniably human. And as much as we probably don’t want to admit it when waxing poetic about unsullied lands, it’s the human involvement that adds all the poetry, adds the magic and the danger to the woods. It’s that old saying about a tree falling in the forest. The important part isn’t about whether someone is there to see the tree fall. The important part is about whether someone is there to tell you what the fall is like, how it made them feel, what it possibly meant, and to give it power beyond that brief moment when it fell. The important part is the process through which that tree becomes a legend, an object of wonder that infects the imagination of the children who hear about the tree by campfire.

Bird specifically chronicles the psychogeography of a portion of South England, specifically around South-East London, including places like Croydon and Bromley, which all abut the shadow of the Great North Wood. But part of his revelation is that the human constructs are often as fleeting as the natural growth, and you don’t need to look any further than the Crystal Palace for an example of that. The difference is that all human structures can do is decay, to try and remind you of their past relevance through sad remains, while nature can burst through not only those remains, but even more recent, more technically sound structures. Nature can peek through modernity and stand as a hint to a richer past.

Bird has concocted a beautiful book with invigorating research and poetic observation. It’s brief and deceptively simple, but it gives a sprawling examination of human history — and the human future — in terms of artful depth that might inspire any of us to take a closer look around at our surroundings. Where do we live? What ghosts exist on our own landscapes? And what from the past is silently standing aside, waiting to be noticed as a marker for what has come before?