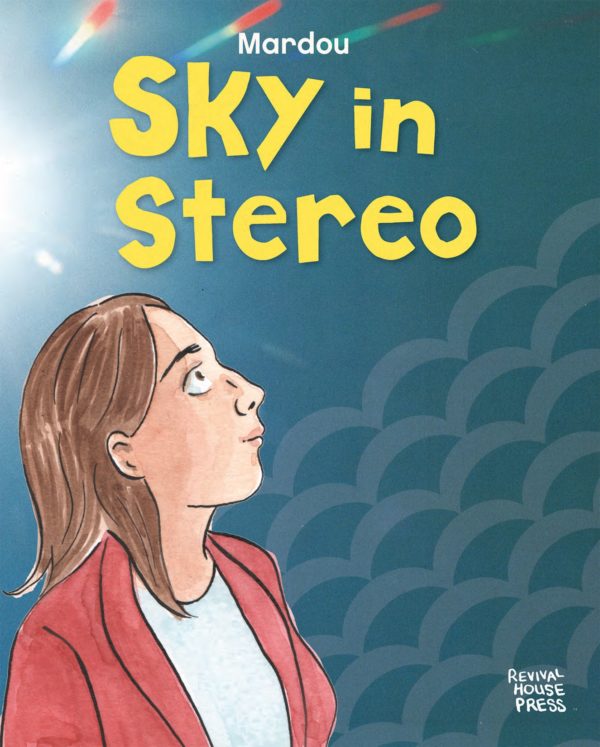

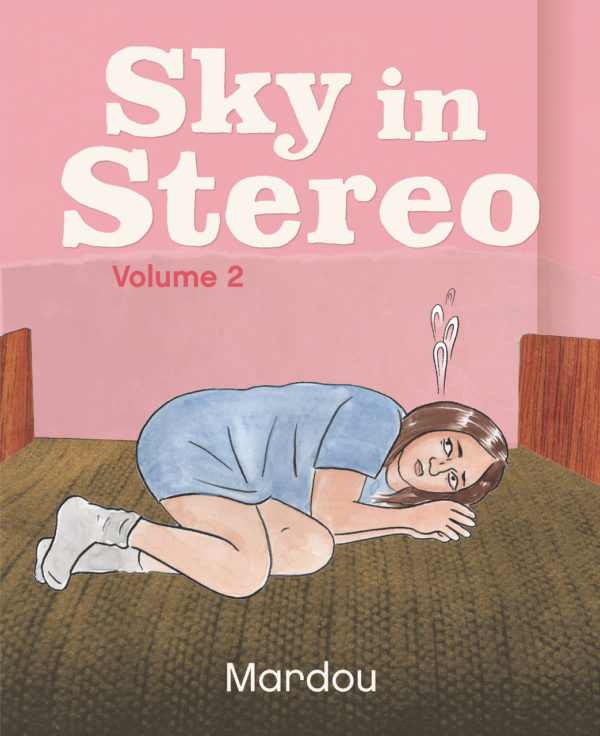

Sky in Stereo Vol. 1 and Vol. 2

By Mardou

Revival House Press

I’ll warn you right now that in discussing Sky in Stereo, I’m pretty much going to give it all away about the events of the first volume. Mardou’s work is good in that way a spoiler shouldn’t really matter though — this is not a work of big reveals, but small realizations, and it’s the way they are rendered that count.

In the first volume of Sky in Stereo, which takes place in the Manchester, England, of the 1990s, we follow teen-ager Iris in a rapid succession of life changes that includes her mother’s conversion to Jehovah’s Witnesses and gets dumped by her boyfriend. The former she attempts to be part of, not out belief but just to be agreeable, but she reaches the limit of her patience with the encroaching demands of the religion that don’t align with her own world view. That creates more of an emotional chasm between Iris and her mother, and the loss of another close relationship, her boyfriend John, sends Iris on a quest for if not exactly meaning, something close enough that she can grasp onto.

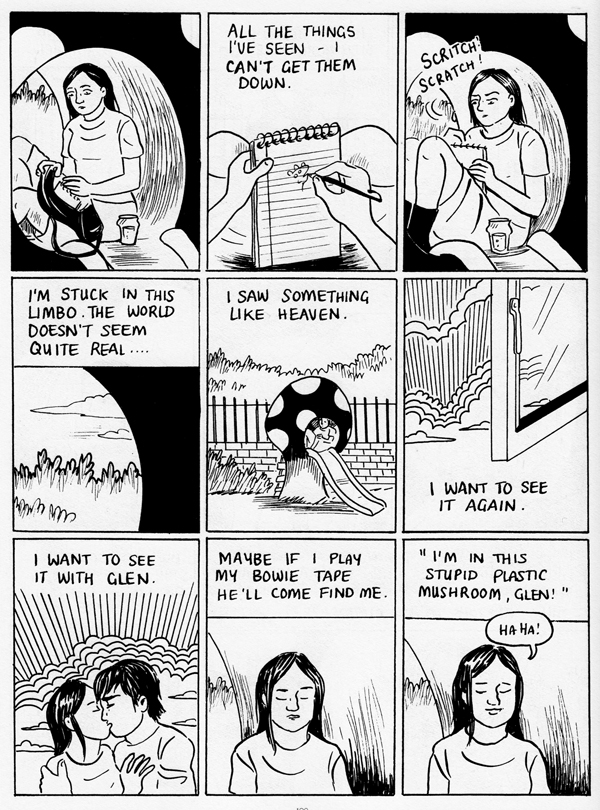

But a quest requires some energy and most definitely a goal, and as Iris sinks into a nowhere job at a burger joint, there becomes little point or enthusiasm to her daily existence, beyond a preoccupation with Glen, one of those alluring bad boys who flirts with all the girls and holds up his drug experimentation as a sign of how dangerous he is. They have a connection, for sure, but Glen is too aloof and Iris too self-defeating, and through a series of listless activities and endless wandering, Iris drops acid and has a confusing personal revelation that bounds into a wandering mission around town that connects all the aspects of the universe into some convoluted order in Iris’ brain. It also finds her in police custody after her mother has reported her missing. Iris is now lost on multiple levels, wandering in a post-acid haze, but mostly seeming just lost to herself.

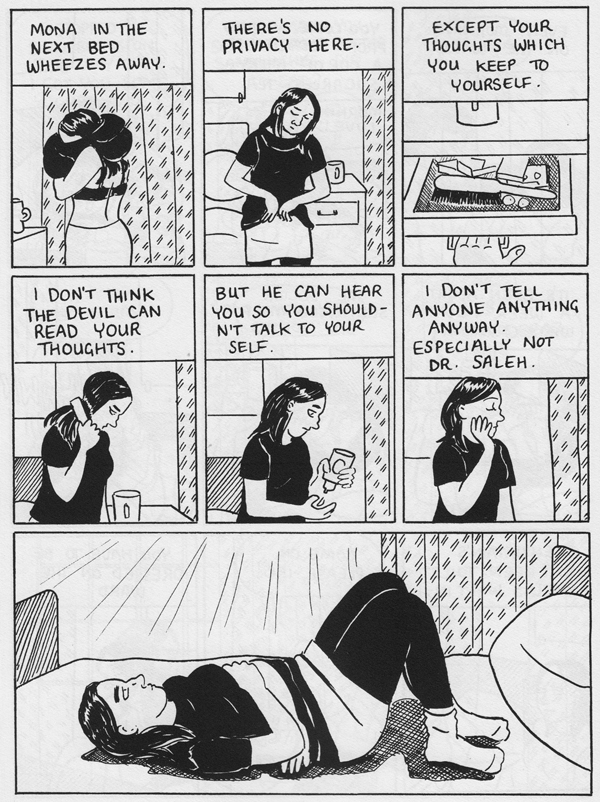

In the second volume of Sky in Stereo, we find Iris is lost physically as well as psychologically. Her trip to the police station morphs into a trip to the psychiatric hospital, which extends beyond the initial few days into an endless claustrophobic retreat. There’s an incoherency to Iris’ perception of what’s going on around her and you’re left to wonder if it’s residue from the acid or something much deeper taking over as she finds herself in distress. Or both?

Regardless, Iris rejects all authority offering her any help. The kindness of professionals is perceived by her as condescending at best and downright sinister at worst, and she flounders in the facility, incapacitated by hostility towards everyone around her, even other patients, and convinced of a wider series of events that is causing this conspiratorial outcome in her life.

But despite the paranoia that has overtaken Iris’ view of the universe, and the insistence on reading patterns as her way of collecting the information she needs to even have a view of the universe, Sky In Stereo’s ultimate conclusion turns out to be a sweet one. While the first volume sets up a rebellious tone that touches on so many symbols of the teenage penchant for defiance, the second implies that there may be a middle ground, or at least a more genuine, personal way of registering discontent that isn’t self-destructive.

It’s here that Mardou makes perfectly clear that she isn’t interested in romanticizing Iris’ trauma, but the entire book leads up to that moment, as Iris reacts to her fellow patients, often with revulsion, but at later points with affection and concern. Perhaps Iris realizes that while so many of the older women she encounters are in a state they have no chance of leaving behind, she still has a chance given treatment and the desire to follow through.

Dutifully pursuing mental health is not generally held up as a romantic archetype, certainly not in contrast to the destructive deep-boy tone that Glen offered, but Iris’ experience with the opposite results surely inform her journey. But in depicting this, Mardou doesn’t reject what Iris experienced in her drug experimentation as not valid. It informs her healing and the result is the idea that every experience is something you can take information from, even the ones you might need to be rescued from. Every experience is important, not just the safe ones.