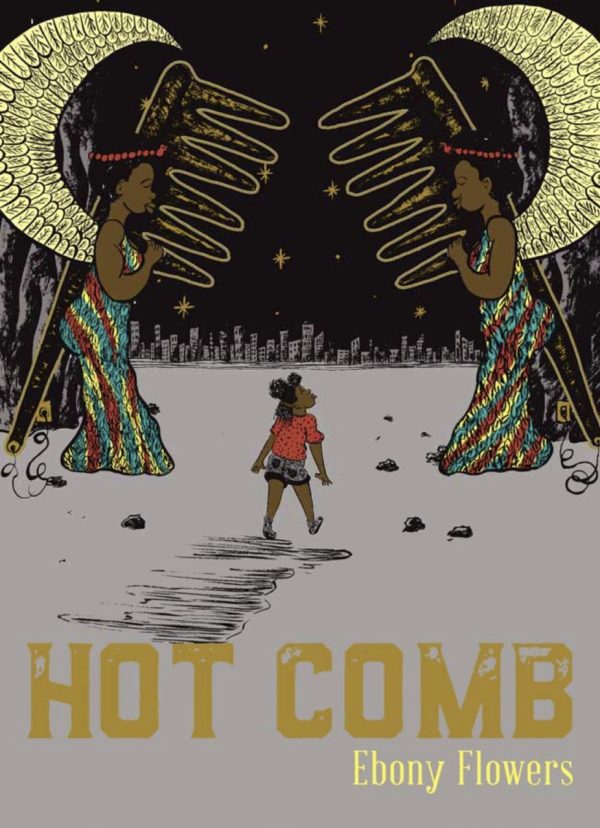

Hot Comb

By Ebony Flowers

Drawn and Quarterly

In Hot Comb, cartoonist Ebony Flowers ushers me into a world I have no experience with and probably will never, the world of African American hair styling. More importantly, she uses autobiographical comics to portray her experiences and relationship with her own hair and uses it to express and examine aspects of African American culture, social and political, and specifically in regard to the experience of black women.

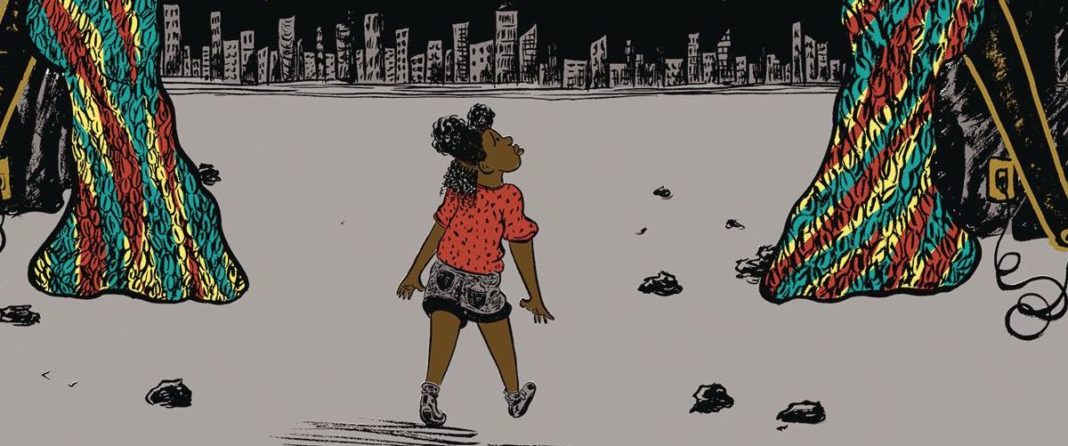

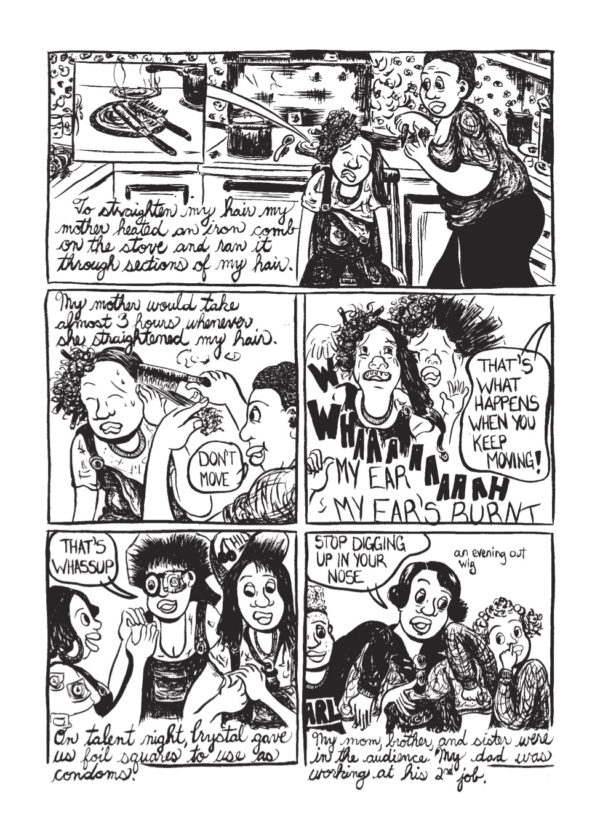

In the title story, Flowers painstakingly documents getting a perm, which is part of the process that straightens out African American hair, also known as relaxing. As portrayed by Flowers, it can be a grueling endeavor that includes physical pain and long hours of waiting and brooding for the outcome before finally getting around to the actual hair styling.

Getting the perm is all part of Flowers’ growing pains. She’s in 5th Grade and has hit a point in life where appearance has begun to matter to her, and as with so many of us, the appearance she seeks is one that is dictated by the larger culture, but also the whims of our peers. She’s going through a period where peer pressure can pack the same wallop as bullying, even when it comes from friends, and Flowers is typically on the receiving end of jabs about her hair. Relaxing it has become a persistent goal for her, and her mother reacts with hesitation and sadness before giving in.

The visit to the salon, though, isn’t grueling. It’s a bit of a revelation, opening up a social space where Flowers’ mother celebrates her personal bonds with hairdresser Dee Dee, and Flowers is given the opportunity to study and observe the conventions and affectations of the gathering of adult women. It’s at this moment we understand that’s part of Flowers’ mom’s sadness — the coming of age moment for her kid.

But it’s also tied into the political implications of straightening black hair. Earlier in the piece, Flowers made plain the uncomfortable feeling her mother had with Flowers mirroring aspects of the white culture she experienced through a friend, and made efforts to see that her daughter was a part of a black community.

Part of that, I imagine, is because of the way whites treat aspects of blacks — cultural ones, but more importantly physical ones and more specifically hair — as novelties. Flowers captures the awkwardness and annoyance of these encounters in several pieces in the book.

Hair plays a role in all the stories in Hot Comb. In one untitled piece, Cora stays at her grandmother’s and despite the best efforts to keep her out of family problems, witnesses a visit from her troubled aunt and later a heated conversation between her mother and grandmother about the visit. Haircare becomes part of what the mother and grandmother do while addressing the problem, while grandma’s wigs serve as props for Cora as she passes the time.

Hair shifts back into being the focus in “My Lil’ Sister Lena” where Flowers talks about her sister’s softball experience being one of the few black kids involved and hair becomes a symbol of not only the difference, but shame. When her teammates become obsessive about Lena’s hair and bombard her with questions that border on obsessive, the relentless begins to weight down on her and she copes in private by self harming, which manifests as Trichotillomania. It’s an upsetting account of the potential destructiveness of careless racial microaggressions, but it’s also an explanation of how a natural physical aspect of a person is transformed into a reason for engulfing shame by the actions of others.

In “New Ad,” hair serves as a common ground between two sisters, a way they can relate to each other, in a larger story about Jasmine’s day with her mom, visiting her aunt. Jasmine’s life is dominated by play and imagination, but a hairstyling session between the sisters reveals hardships of their childhood, in sharp contrast to Jasmine’s, and the animosity Jasmine’s mother feels about that contrast. One sister styling the hair of another becomes part of a ritual that allows them the space to step out of reality and into an important dialogue.

Hair conversations also become a point of calm in stressful situations when three women in Angola prepare for a day at the beach. Amidst the everyday street chaos there brought from kids and traffic, as well as unkempt roadways that almost obstruct any clear passage to the beach, hair care — particularly in context of not being able to find reliable products or hairdressers — becomes the chat go-to as they pass the time.

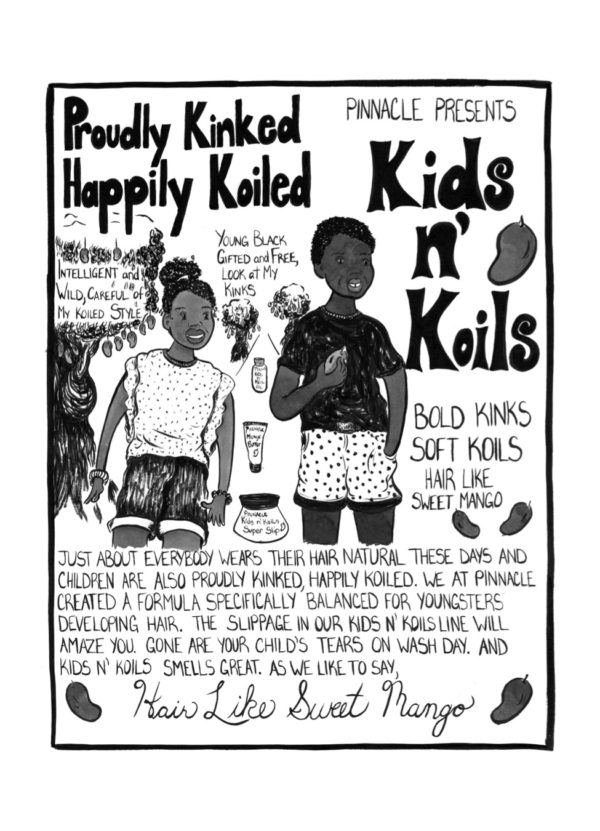

Between her stories, Flower intersperses depictions of satirical vintage hair care products for African Americans which in their promises of hair revitaization also seem to be pointing to some greater personal desire for self-fulfillment in context of heritage. Certainly that’s something that so much advertising attempts to do, but in this context, it adds a layer to what Flowers portrays in her stories.

Hot Comb is Flowers’ debut book and it’s a hugely impressive one, placing Flowers’ intellectual strength upfront. On one hand, these are slice of life stories, filled with life and energy, and the product of someone who is obviously a keen observer of humanity. Flowers’ dialogue is so natural and her portrayals of conversation so realistic, and her words are in perfect partnership with her cartooning. Her figures are alive, with rich body language, and Flowers knows how much and how little of their world to render to give a fuller picture of the characters and their situations.

But Flowers’ skill at depicting the intimate are just one aspect of how fully-realized her talent springs forth in this book. What makes it so special is the way she wraps these elements around larger themes of race without ever making you feel like you are reading A Very Important Work With A Heavy Purpose. Rather, Flowers lets the characters be themselves, lets the situations unfold, and by bringing these together, lets the big themes come out naturally and — more important — decisively.

The narratives in Hot Comb make the point. The characters make the point. You learn through the experience. You learn through empathy. Hot Comb is like a masterclass in how to make comics.

Comments are closed.