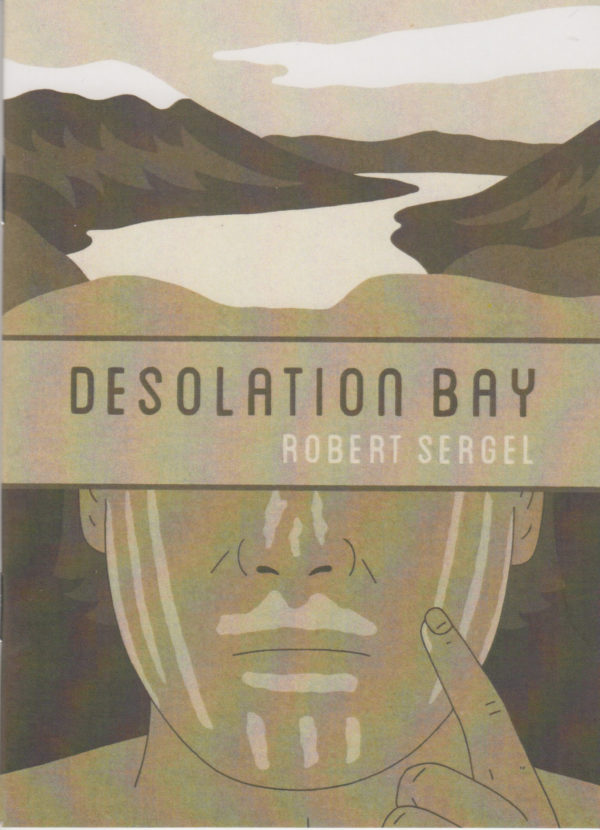

Desolation Bay

By Robert Sergel

Kilgore Books

Portraying the pre-colonial beliefs of the Selk’nam, or Ona, People who lived in parts of Argentina and Chile, in Desolation Bay Cambridge, MA-based cartoonist Robert Sergel doesn’t get picky with context in this brief work that holds devastating meaning beyond its 24 pages.

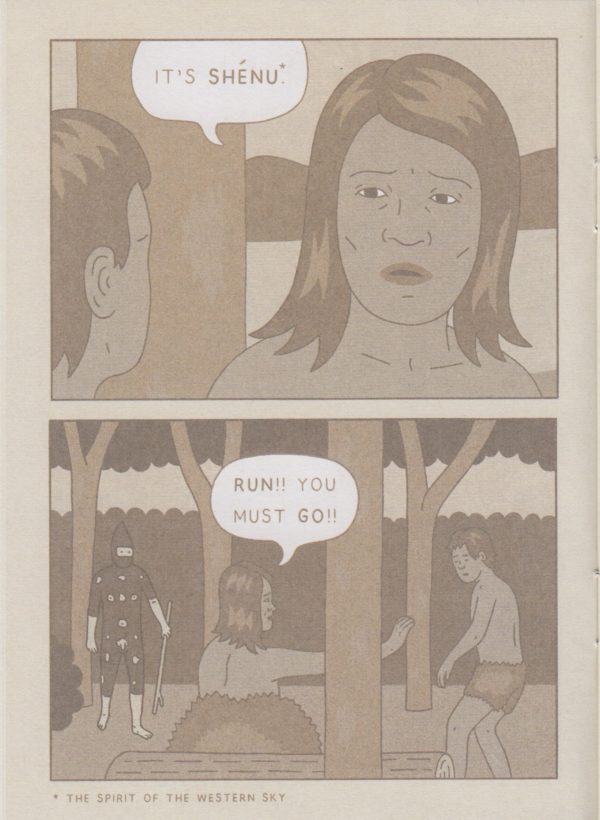

It’s the initiation ceremony called the Hain that Sergel concerns himself with here, meant for males to mark their ascendency to manhood, but with a darker purpose that targets the women of the tribe. The events unfold with no explanation, building a creepy and weird residue in your mind until the conclusion makes it even heavier and more sinister than it was in the first place.

The Selk’nam managed to survive longer than many of the indigenous people of South America largely from avoiding Europeans altogether, but being able to delay this interaction until the 19th Century didn’t help in the big picture. The Selk’nam genocide was enacted close to the 20th Century, which saw area ranchers colluding with the Chilean and Argentinean governments to slaughter off the tribe after thousands of years of nomadic existence in the region. Those that survived were confined to a concentration camp.

Sergel only hints at this tragic horror to follow, leaving his story off with a glance of an arriving Catholic missionary, which is helpful in not infantilizing this portrayal of native culture, allowing the ritual of the Selk’nam to stand on its own. In those terms, the Hain is revealed as its own tool of oppression, built on religious belief in order to demonize a section of the population. Part of the lesson, I suppose, is that any culture has that aspect, and sometimes it dominates. Magical thinking and fear-mongering is a constant through history, regardless of the stature of the culture that employs them. And women have often been the objects of this control.

But Sergel also steps back from any in-your-face lesson. Events unfold soberly and sparingly, and whatever emotion you bring to it is your own. In the end, it’s as much a presentation of how to approach incidents in history as it is the incident itself, and the fact that it’s achieved so fully in so slender a volume is a testament to Sergel’s talent.

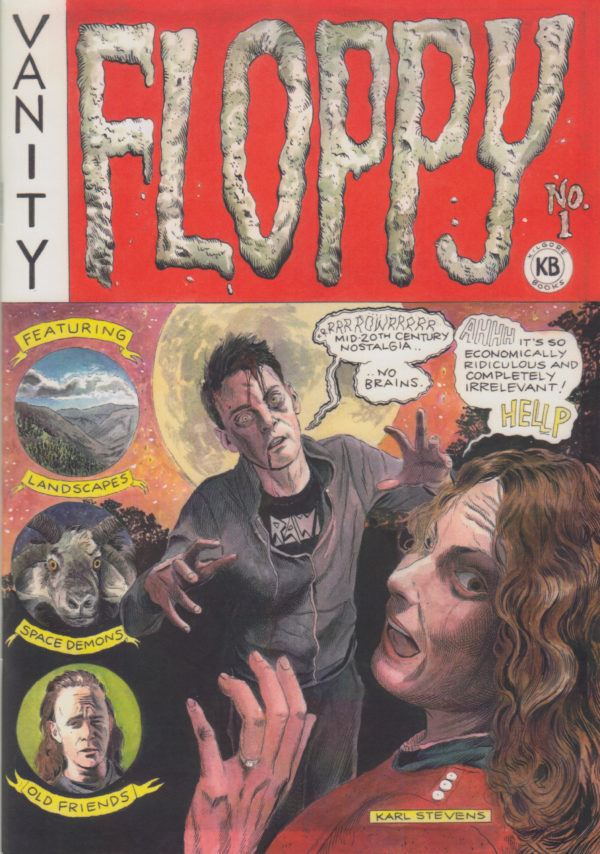

Floppy #1

By Karl Stevens

Kilgore Books

I first encountered the work of Boston area cartoonist Karl Stevens in his standalone book The Winner, which came out last summer, and I appreciated his approach to autobiography. His work wasn’t like that of all the other autobiographical cartoonists out there and I think it’s because there is an unacknowledged pattern to the way much autobiographical work is delivered. Stevens’ delivery seemed to kick away the possibility of a pattern.

Stevens is taking a similar approach with Floppy #1, the first issue of what he describes as “an ongoing classic comic book art project,” which is to say, the first issue of his new comic. I don’t know how often it will appear, but I’m interested to see Stevens’ ideas applied to a recurring format.

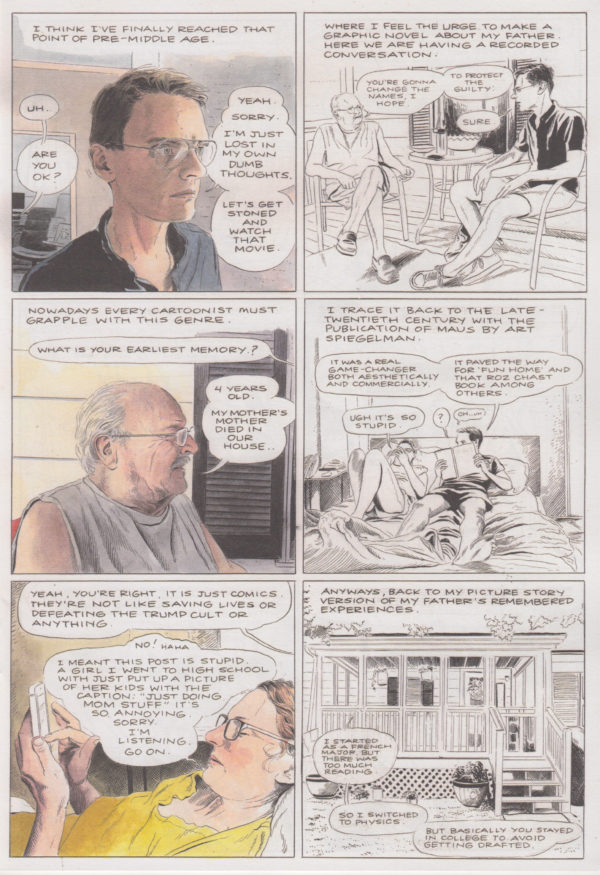

All that said, Floppy #1 is very much an extension of The Winner, except without the succinct theme that feels properly-addressed and concluded by the end. In this way, Floppy #1 is much more of an investigation in real-time, with no promise of anything substantive at the end other than having shared a journey with the creator. That’s fine with me, because Stevens is an incredibly-talented writer and artist and even if unpredictability might be considered his personal guiding pattern in the work, it has the strength inherent to what it actually means — that is, you know something unexpected might come next, but at least it’s unexpected.

In this volume, there are many pages spent involving aging from various perspectives — sometimes grappling with the ragged appearance of friends, sometimes questioning whether it’s time to move on geographically, sometimes noticing unnerving new dysfunctions of your own biology. Aging also wraps in the experience of your parents — in their growing old, in your watching them growing old, and in their talking about their youth as something so far away and part of what seems like a different reality.

But Stevens also takes some asides into more fantastical scenarios, just as he did in The Winner, such as the mundane mission unexplained mystical agent and a dream about a natural disaster in Boston.

In the most ordinary way, this could be described as an anthology, but Stevens doesn’t provide any boundaries. No titles. No little ‘The End’ dangling where they seem they should be. Instead, one segment bleeds into the other — or are alternately obstructed by the arrival of a new scenario. It’s the representation of mind ablaze, pleasing itself and offering itself to you, accessible in its experimentation and accomplished in its conception. I am looking forward to more.