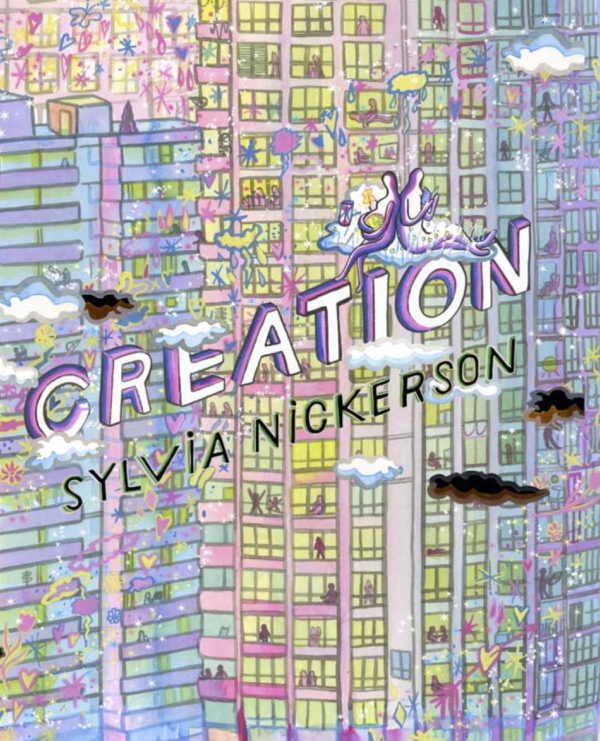

Creation

By Sylvia Nickerson

Drawn & Quarterly

As a resident of Hamilton, Ontario, cartoonist Sylvia Nickerson hasn’t allowed herself to become entrenched solely in her own concerns, despite recent motherhood. She understands that the lives of the people around her directly affect the health of the city she lives in, and these have the capacity to conspire against her own wellbeing, as well as that of her child. She also just has a soul, so she’s concerned by the gentrification she sees that displaces other human beings and has a role in the rise of crime and drugs, and other unnecessary wreckage of human life.

Nickerson devotes Creation to all the thoughts she has on these subjects, darting between aspects of her own autobiography and the scope of a wider tide in Hamilton that sweeps through regardless of the human cost.

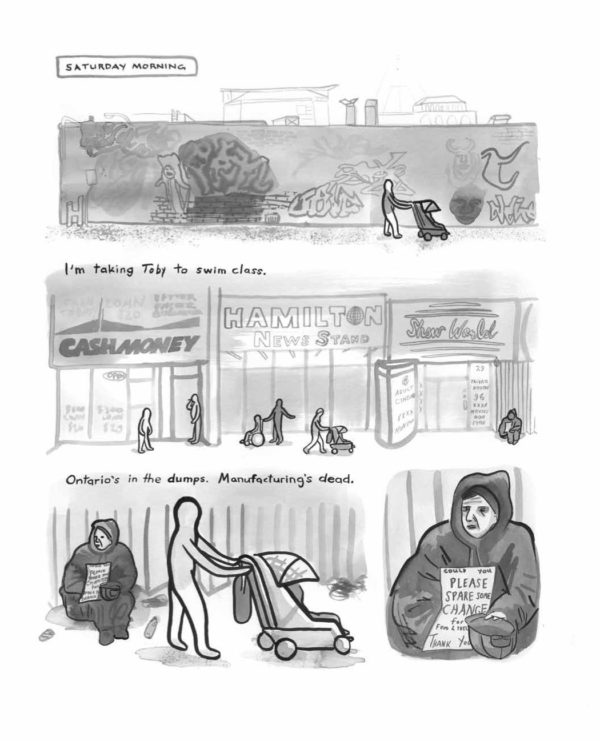

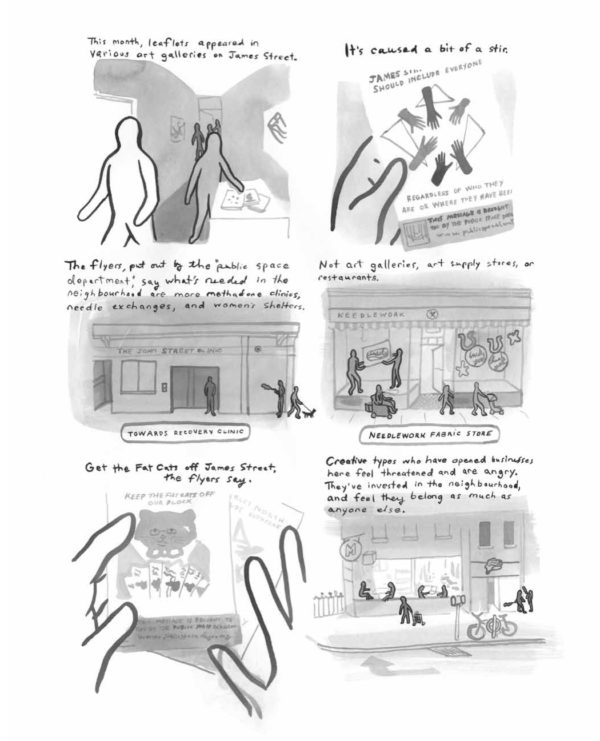

As Nickerson says in Creation, the town that sells itself as “the best place to raise a child” is one that she sees as a place “where so many dreams had come to die.” It’s a place where industry died, as it has in so many similar cities, but where redevelopment is happening as part of a campaign of economic displacement — that is, condos are being built. And art galleries have arrived.

Nickerson has one of these galleries, but something nags at her. As time has passed, as she’s become a mother, she’s also shed that part of her that obscured reality from her eyes. It’s the part that focuses less on the self and begins to map out the terrain in proximity to the safety and survival of offspring. And Nickerson realized that art studios, including her own, were an instrument of gentrification. Artists are literally transforming the neighborhood, but part of effectively doing that involves taking living space away from people so that landlords can get a higher rent from artists coming in who hope to transform the neighborhood.

As Nickerson pushes her stroller through the city, she witnesses, and records, drug overdoses, homelessness, poverty, and more, all at an overpowering level, and what she observes causes her to examine the human condition in context of it all. She observes that between birth and death, “it seems mostly to be about who has power over who” and “in loving, we give our power away.” It’s these two sentences in Creation that wind through much of the book, tying themselves around the tragic circumstances portrayed, and they put into philosophical terms why charity usually struggles and greed usually dominates — because charity requires loving and therefore has no power.

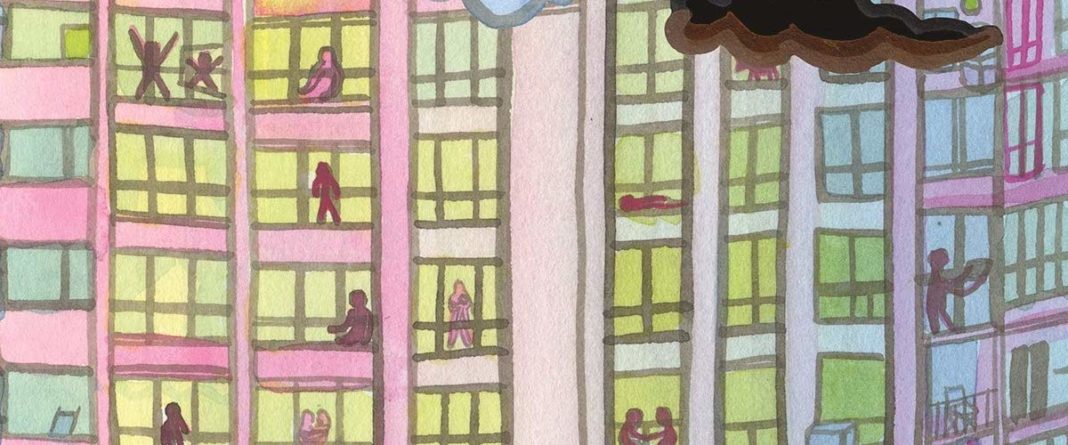

Even as Nickerson gets intimate in the moments she records while she wanders, she also steps it back and fills Creation complicated, cluttered spreads that cram together many aspects of the city, both structures and life into a crazy, kinetic super organism often filled with tragedy and anonymity, frequently populated by faceless people and ghostly human outlines going about their business, or being without a purpose. Either way they are bombarded with signage and streets and garbage and toxic waste and skyscrapers and other ghostly human outlines.

In many ways, what Nickerson ends up advocating is the idea that all you can really do is wait for change — proactively, sure, but with patience — and the thing that is most in your control is how you feel about it. That may be oversimplifying it, but the enormity of what she documents in Creation versus the intimacy of the conclusions she comes to suggest that’s a reasonable conclusion, especially if you are tending to your own well-being as a caretaker for a small person you don’t want dominated by hopelessness.