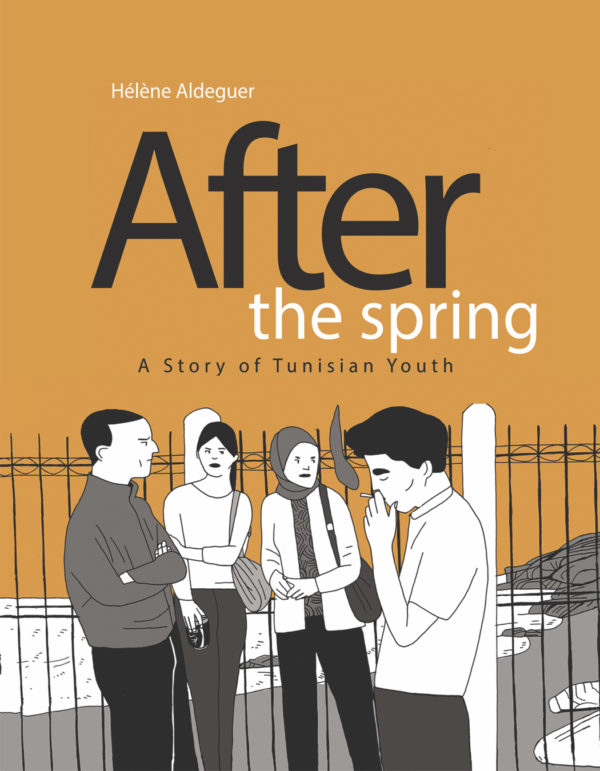

After the Spring: A Story of Tunisian Youth

By Hélène Aldeguer

IDW Publishing

In the popular imagination of the Arab Spring, it’s the imagery in Egypt and Syria that are typically evoked, but it’s important to remember that the domino effect began in Tunisia in late 2010 when a street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in response to government harassment. This set into motion the Tunisian Revolution which sent waves across the region that resulted in protest and violence in Egypt and Syria and also Yemen, Morocco, Oman, Libya, and Bahrain. This wave of action last until half-way through 2012 as violence escalated and some regime change resulted, mostly unsatisfactory as they unfolded.

In Tunisia, this stretch of time is known as the Tunisian Revolution, or the Dignity Revolution, which resulted in the overthrow of President Ben Ali at the beginning of 2011, and the country descended into a state of chaos overseen by an interim government. Later that year, the Ennahdha Party took control, winning 41% of the vote in elections, but dissatisfaction and disagreement within the country continued.

These are sweeping and complicated events, but Hélène Aldeguer attempts to streamline them in After the Spring: A Story of Tunisian Youth by framing the larger events through the context of more personal struggles of Tunisian young adults as they react to what is unfolding in their country and try to navigate their own lives in such circumstances.

After the Spring picks up in 2013 as Saif arrives back home in El Kef from the larger city of Tunis to find protests raging and his brother Walid taking part. As Saif pulls his brother from a confrontation with police, he learns quickly that dissatisfaction with the Ennahdha is escalating into violence and creating short term memories where the totalitarianism of Ben Ali is being forgotten in favor of nostalgia for perceived stability.

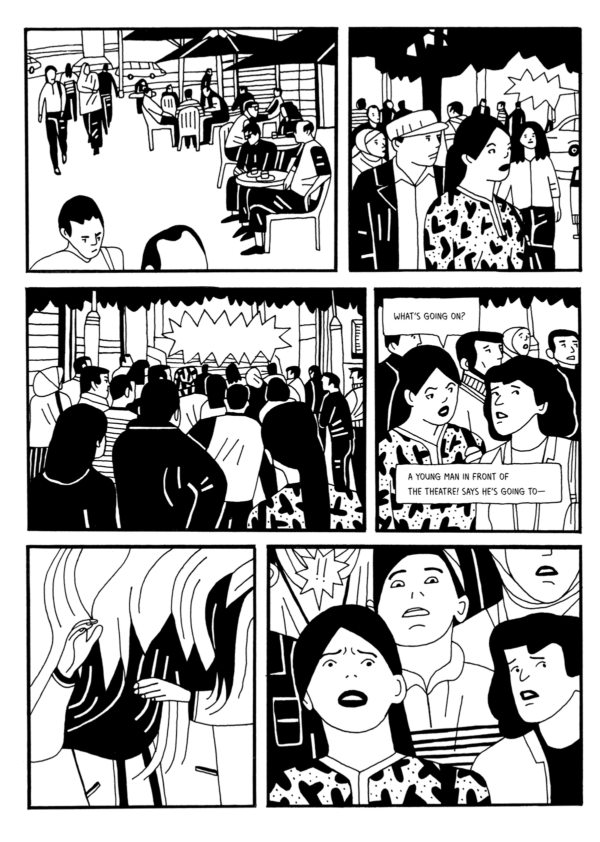

Back at the university he attends in Tunis, Saif checks in with his friends, Chayma, who focuses on her studies and seems removed from the conflict, and Aziz, who has quit school and is struggling to find tolerable work that pays an acceptable wage in hopes that he can make an overture for marriage to Meriem. But their personal struggles are about to, yet again in their young lives, become secondary to sheer survival in a country where the political struggles have a way of commandeering everyone’s focus thanks to a political assassination that results in further protests and riots. When a young man immolates himself in front of a crowd, it resonates as an alarming symbol of hopelessness that many of the characters feel, a despairing cry that there is no future.

Aldeguer follows her characters as they try to balance their own decisions against the chaos that has been unleashed in their country and gives no sign of abating and After the Spring asks plenty of important questions. How can you make plans when there is no evidence that there is a tomorrow that will come? And what do you do to create a tomorrow for yourself? Do you leave the country? If you aren’t capable of getting out of there, do you go ahead with your personal plans and take it on faith that a tomorrow will arrive as it always has?

As the dramas unfold in After the Spring, Aldeguer offers points of reference explaining the event, and after the story provides a more fleshed-out explanation of the political significance of what she references within the story itself. As I said before, these are sweeping and complicated matters and I caution that one reading of the book may not be adequate to cement everything in your brain into anything resembling a cohesive map of recent Tunisian political history.

But Aldeguer does an astonishing job of bringing these elements together into one book, and not an overlong one at that. It’s a reminder that revolutions are about ordinary people, that oppression is about ordinary people, that riots are about ordinary people, that police states and government crackdowns are about ordinary people. We can bandy around political philosophies and lines in the sand, but most conflicts are about ordinary people trying to overcome the quagmires created by politics that do no service to their survival, and Aldeguer’s story skillfully pushes that truth into human terms we can all embrace.