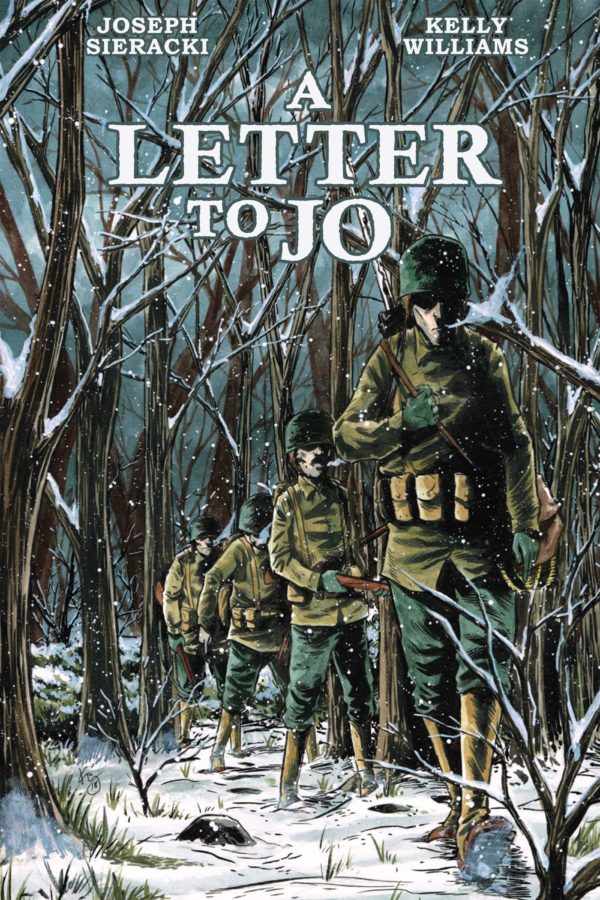

A Letter To Jo

Written by Joseph Sieracki

Illustrated by Kelly Williams

Lettered by Taylor Esposito

Top Shelf Productions

One of the biggest stories America told itself in the mid-20th Century was the one that involved the ability of World War II veterans to just sink back into normal life following the war. It wasn’t that we in no way acknowledged that war was tough on a person or that some victims of combat trauma existed, it was that we brushed off the suggestion that just about every man who served might have been negatively affected by their experience, many to the point of debilitation.

I think that’s partly due to the desire of our society to move along. Americans have always had an obsession with the idea of things “getting back to normal,” which points to the strange reality that Americans think they know what normal is and believe it exists. But it’s that assurance about the existence of normality that makes psychological issues and our ability and willingness to address them in the open so lacking. Ill health of the mental variety was not normal in the mid-20th Century and our particular view of manhood especially in regard to warfare did not allow for millions of men to be open about what they experienced during the war and how it affected them.

This created a broken generation of men whose damage echoed through their families. Most people my age have someone in their extended family for whom this was the case, a guy that causes other people in the family to whisper the words, “he came back from the war different,” but they didn’t know how to deal with the difference and the man didn’t know how to express what caused it.

I thought about all of this as I read A Letter To Jo, which is based on a letter that Joseph Sieracki’s grandfather wrote his grandmother at the end of World War II. The book starts with a crucial prologue, a text piece written by Sieracki that recounts the way his family looked at his grandfather, as well as Sieracki’s personal relationship with him. It’s the classic story of a man haunted by his experience but incapable of taking the needed steps to exorcise himself of their damaging aspects and having that deficiency come out in sometimes destructive ways towards some family members, while also managing to be soothed by certain other family members.

Sieracki’s grandfather, Leonard, met his grandmother, Josephine, in high school in Cleveland, Ohio, 1941, and dated despite the objections of their immigrant parents who wanted their child to date someone of the same ethnicity — Leonard was Polish, Josephine was Italian. Directly after high school graduation in 1943, they became engaged, but shortly after that Leonard was shipped off to the war, and they parted with plans to marry upon his return.

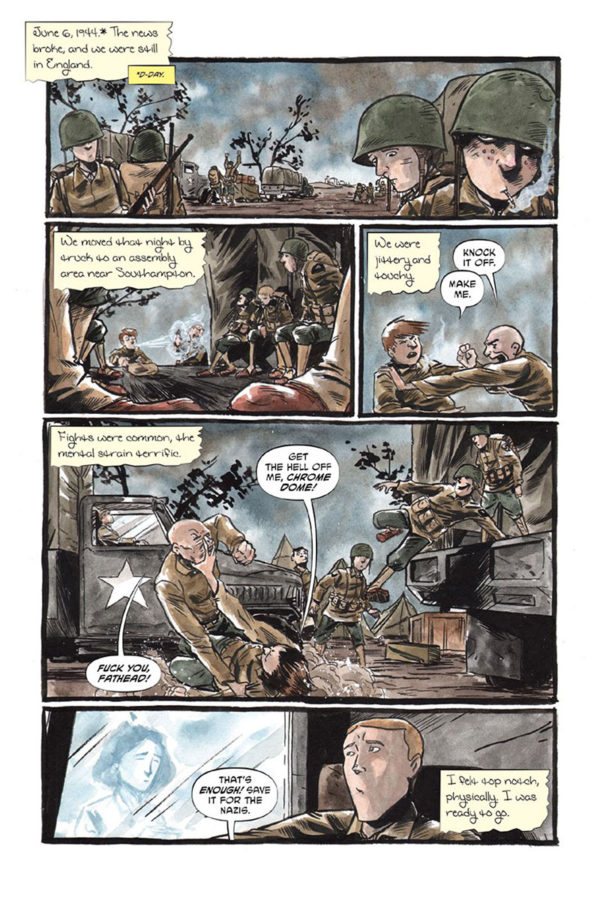

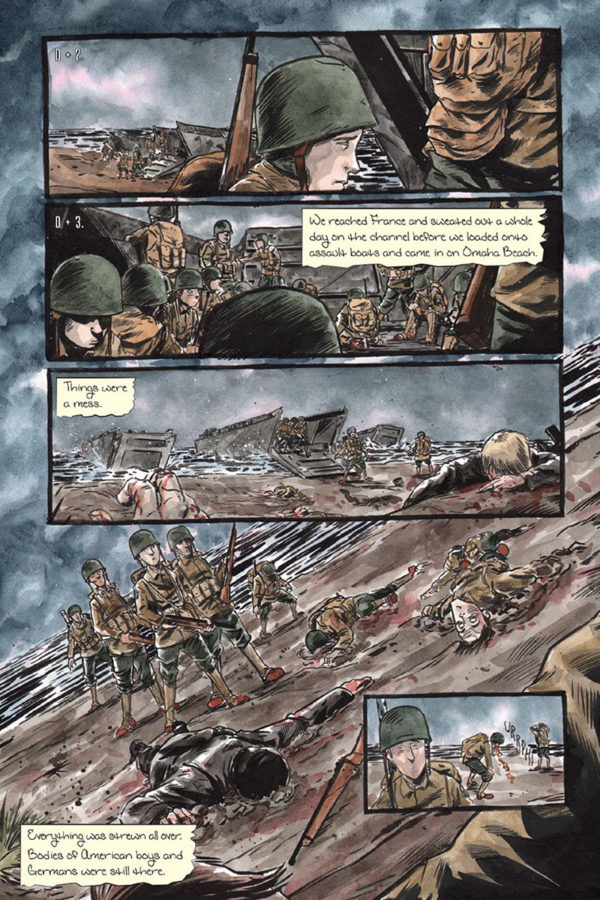

Leonard’s first experiences in the Army were during training when everyone is working out their kinks with each other as well as just trying to get in a mode where they are useful in combat. It’s an idealistic time and it seems like the fear is sometimes overcome by excitement. It doesn’t seem to me that it really prepares anyone for war, especially given the reality that this is a bunch of 18-year-olds with literally no life experience beyond their hometowns, schools, jobs, etc., so it’s no surprise that their first entry into the warfront is a literal nightmare of dead bodies with terror still registered on their faces. Bloody corpses are strewn left and right on Omaha Beach and the fresh-faced new soldiers have to trudge through them to get to their own fate.

This is the point that Kelly Williams’ artwork really takes over A Letter To Jo. The text remains grounded in Leonard’s experiences with some history-based embellishment by Sieracki in order to capture the reality of the soldiering experience then. Williams keeps the art grounded in this same reality but with the terror of the situation also closing in, eventually rendering Leonard’s entire wartime experience as a dark, hellish landscape of violence and fear that he is determined to remain optimistic about. In fact, the light he tries to cling to with his spirit is all he has to fend off the darkness that encroaches. There’s a horrible beauty in Williams’ depiction of the war experience, like isolated segments from a Bosch painting transported to the war in Europe.

The darkness eventually gets inside Leonard, but it shares space with the light and that represents his permanent battle and the battle of so many other men following their war experience. What A Letter To Jo accomplishes is placing that personal experience of Leonard in a wider context, the war experience as well as the romance with Sieracki’s grandmother. It is, truly, the American story of that era. As we become further away from those events and those people, and as we face our own new versions of what they went through, it does us good to look deeper into what they experienced and to disregard the old stories of the times in favor of newer understandings so that we don’t repeat the challenges the World War II veterans and their families faced as they tried to “get back to normal.”