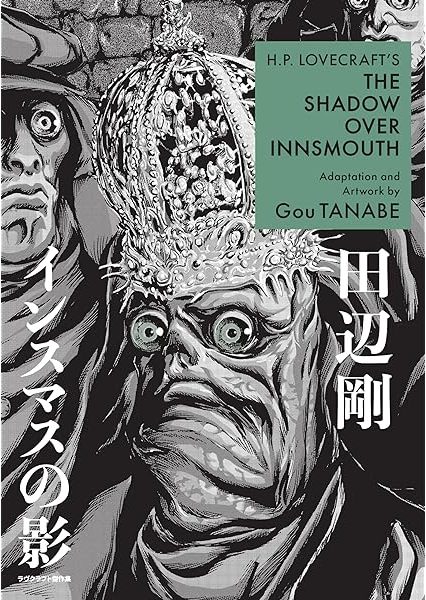

The story, the only one to have been published in book form during Lovecraft’s lifetime, stands as one of the most popular from the author’s body of work. It follows a man who decides to stop at the fishing town of Innsmouth on his travels, a place known for housing a cult that runs by the name of The Esoteric Order of Dagon. The man is interested in the stories of deformed townsfolk and the strange artefacts they’ve accumulated over the years amidst rumors of devil worship and human sacrifice. His decision visits upon him a series of terrors that’ll consume not just his sanity but the very essence of reality as well. And then come the fish people.

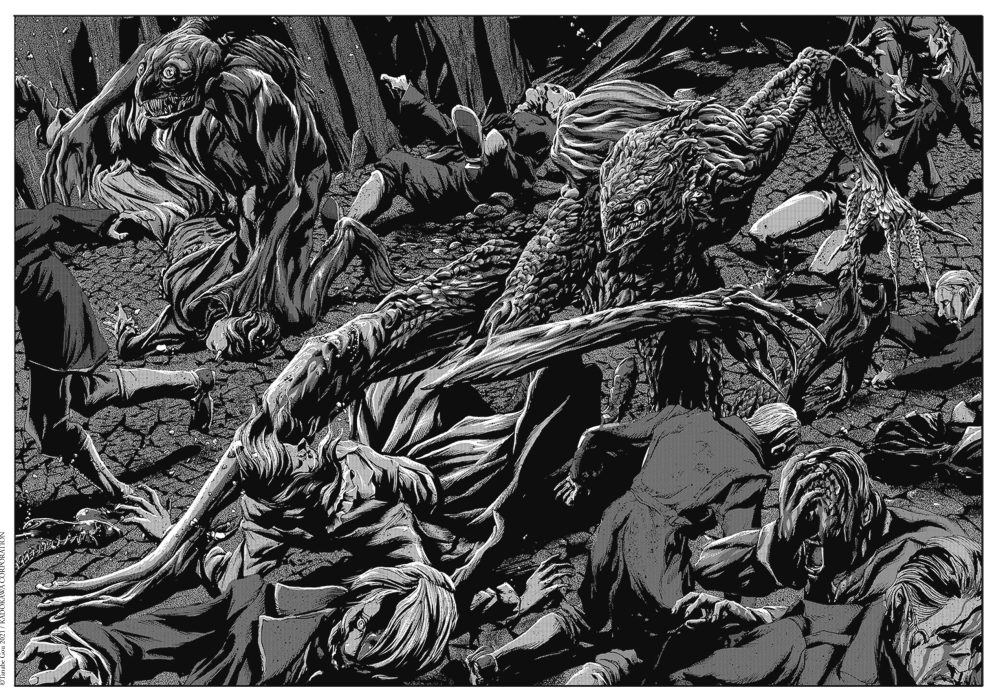

Lovecraft stories tend to hold back on the expected eldritch horror in favor of mounting terrifying closing sequences that reveal their monsters in momentous fashion. Hints of the scarier things are sprinkled throughout, teasing the dimensions of the dark entities that hide on the edges of the seen. Innsmouth pulls the veil back earlier on, letting its monstrosities be a more present danger and a more constant reminder of the horror that’s taken residence in the corrupted fish town. Gou Tanabe takes full advantage of this to drop in as many creatures as possible whenever the opportunity arises.

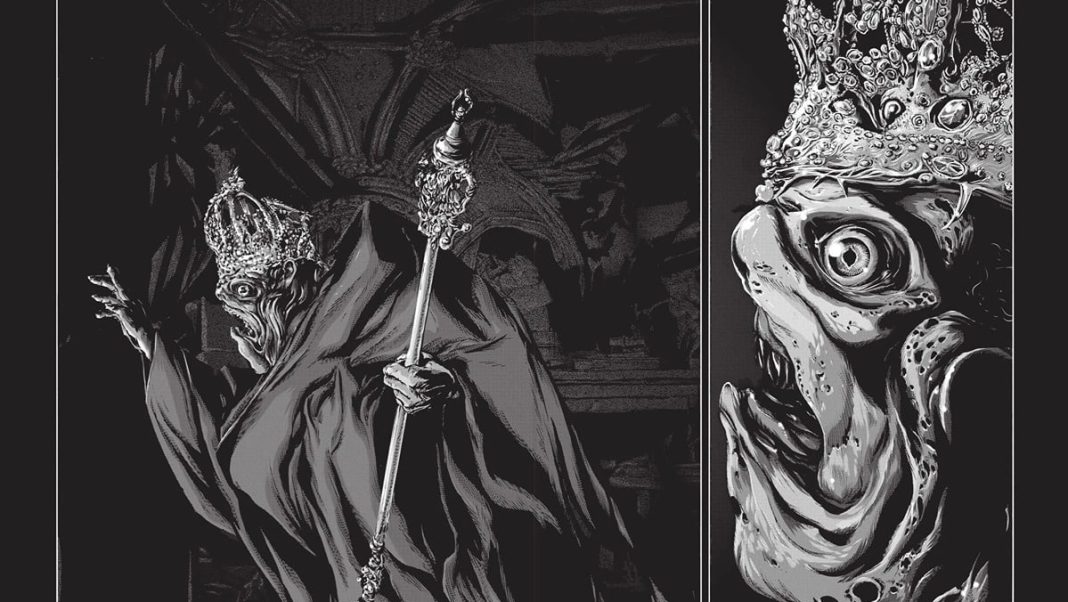

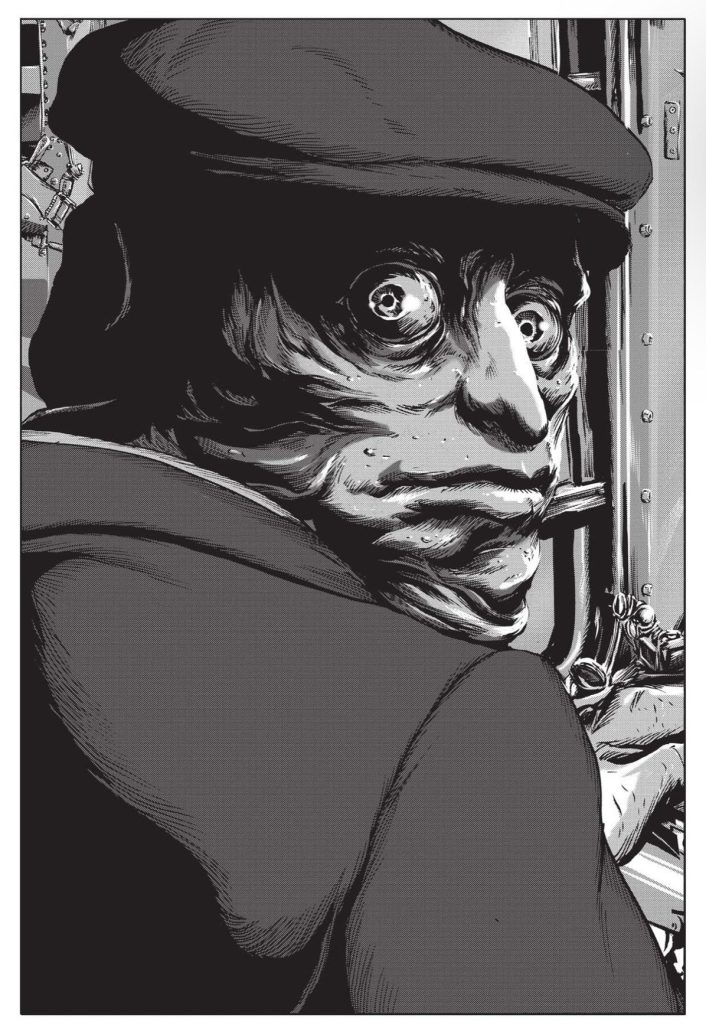

Special mention is owed to the creature designs. It’s here that Tanabe succeeds with confidence where many others falter. The otherworldly and ancient quality of Lovecraft’s monsters are given the twisted and macabre visualizations they deserve. In The Shadow Over Innsmouth, the amphibian look that permeates over the townsfolk and the sea creatures is given life with details that communicate centuries of story on visual level first. One look at them and you know a very old and wise kind of evil has taken over. They just possess a presence that makes holding the very pages they’re in a test of bravery.

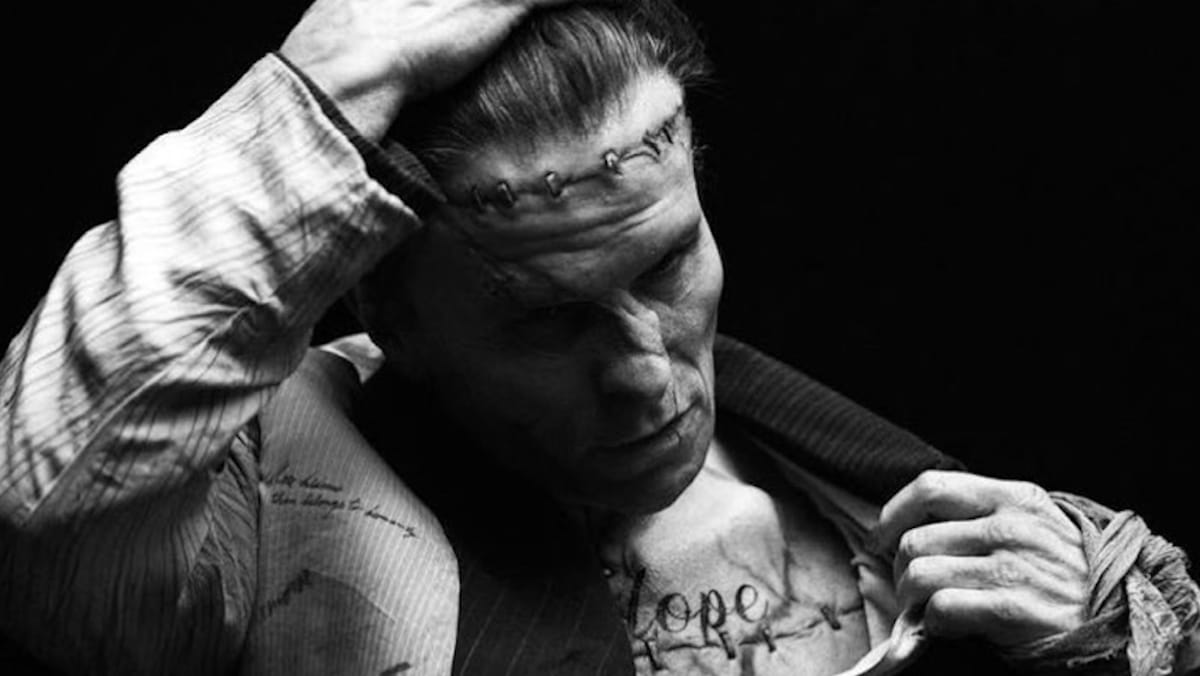

Rows of sharp teeth, vicious claws, and menacing eyes feature in each individual drawing of the creatures, regardless of whether they’re at the forefront or in the background. Tanabe bottles that sense of myth and history Lovecraft imbues the cursed town with to the brim, producing one of the most faithful interpretations of the lore in existence. Only Stuart Gordon’s 2001 adaptation Dagon (which is an amalgamation of the titular short story with key parts of Shadow Over Innsmouth) comes close to reproducing Lovecraft’s terror as close to the original. The town and the creatures’ look in that film benefit from well-researched set designs and practical effects, which allowed Gordon to stick quite close to Lovecraft’s descriptions in his attempt to sell viewers on the terrors Lovecraft put on paper. But Tanabe goes further by giving a more complex sense of terror to the town’s backstory and the deals it struck with cosmically dangerous beings for bountiful but deceptive riches. In other words, Tanabe’s take is scarier.

Gou Tanabe’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth is a superior example of horror adaptation. It shows complete understanding of the source and an eagerness to terrify even further. It’s only second to the original, which is saying something. Replicating prose horror into sequential art horror is no small feat. That is, no small feat for anyone except Gou Tanabe.