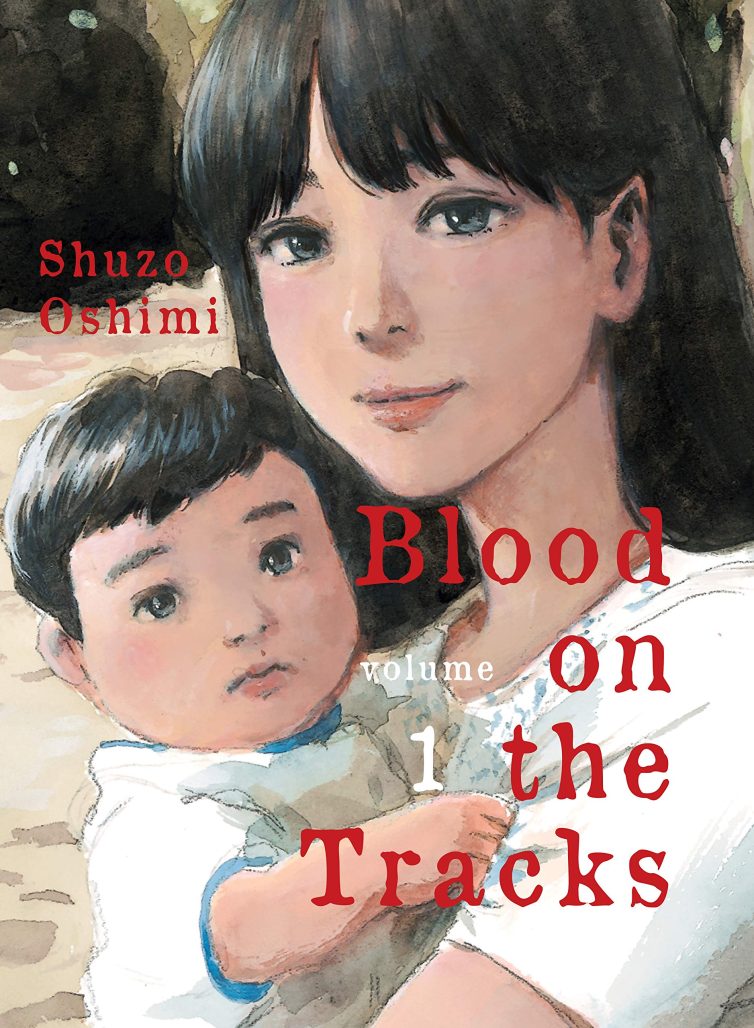

Blood on the Tracks centers on Seiichi Osabe, a kid with an overprotective mom (called Seiko) that unravels before him with a darkness that mounts until it absorbs everything. That’s as much as I’m tempted to say given that the story’s events trickle out with careful consideration as to pacing and emotional heft. Just know that something terrible happens that starts Seiichi and Seiko on a very bleak and dangerous path.

Oshimi peppers the story with hidden suggestions that make the reader question why Seiko is so overprotective. At points it comes across as something potentially incestuous, but not acted upon. Later it pivots into a kind of jealousy or fear of losing her closest human connection to new friends or a girl with a crush. Seiko is the picture of isolation, a world that orbits alone without much of a chance for interaction other than her son and her distant and oblivious husband Ichirō.

Because Oshimi puts Seiichi under the microscope for the entirety of the story, painstakingly dissecting his shock and immediate trauma as his mom’s behavior becomes more unstable and intimately destructive, every reveal or incident authored by his mother hits like a piano on freefall from high on up, distorted notes and all. There’s this sense that reality is hanging by a thread. That domesticity is a failed enterprise that people just keep forcing themselves into without seriously considering the catastrophic consequence of familial collapse should the endeavor fall short.

In a sense, Blood on the Tracks is a slow-motion car crash that puts parents on the front seat fully aware that the damage will carry over to their kids and essentially turn them into broken people for the rest of their lives. This makes the reading quite uncomfortable and personal, but one that’s hard to turn away from (much like a car crash).

Watching Seiko break down little by little, but with mounting dread and force, drives the story just as much as seeing Seiichi’s personality crumble after each revelation forces him to reconsider who his mom actually is. Oshimi plays around with the idea that we never truly know who our parents are as people when we’re still growing up. The “mom” identity takes over and colors everything for us at younger ages and going beyond it feels like an intrusion, as if knowing more is forbidden. Fears of disappointment start settling in, that one’s own kids won’t be able to process the idea of having a parent that has regrets or broken dreams as a direct result of choosing to have a family.

What’s sinister in Blood on the Tracks is that Seiko’s character has essentially turned Seiichi into her savior. Losing him to friends, girlfriends, or time means she stops becoming necessary, at least in her own mind. What does life look like when the object of your affection, which borders on obsession when not kept in check, starts pulling away to become his or her own person? This question leads to some terrifying realizations that create a certain kind of human horror that gives any ghost or demon a run for their money.

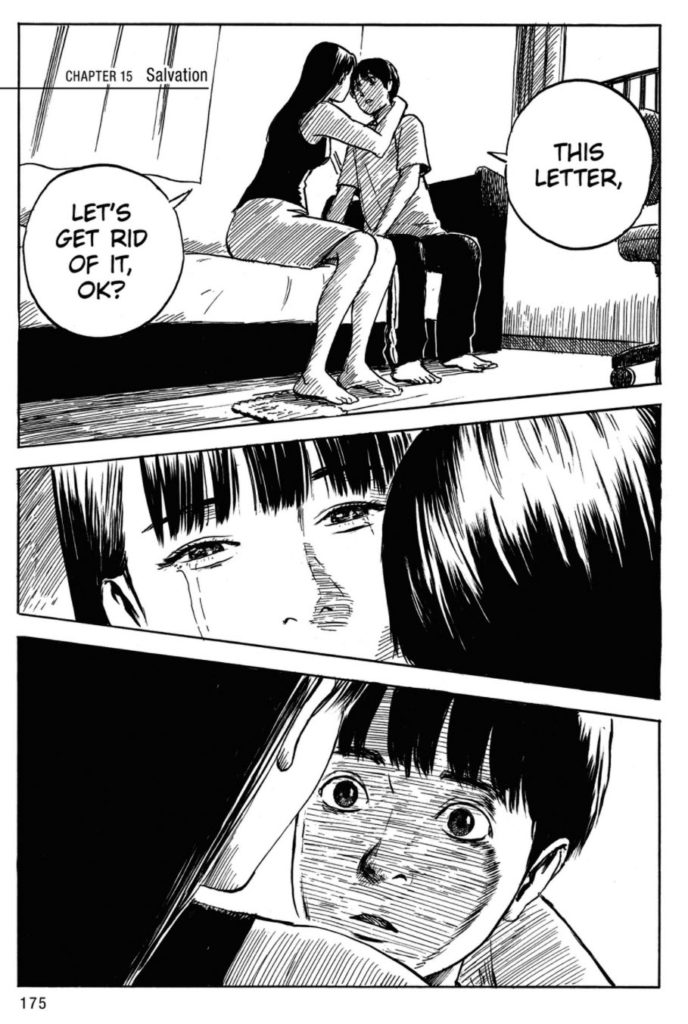

Adding to the disturbing quality of the book is Oshimi’s visual approach. It’s quite natural and grounded, but whenever we see Seiko from Seiichi’s point of view, the imagery freely moves between heavenly and bright to dark and overbearing. It manages to capture the state of their relationship at certain points of the story and how close to catastrophe they can be at the drop of a hat. Then, something happens that stays the complete disintegration of their connection and the visuals shift to accommodate the change.

The same applies to facial expressions. Seiichi’s in particular perfectly capture the horror of witnessing his mother cycling through emotions to hide her darkness from anyone looking in on her. The faces he puts on are faces we’ve put on ourselves when our parents stop conforming to our ideas of them. It’s not hard to feel for Seiichi because at one point or another, we’ve been Seiichi.

There are shades of Edgar Allan Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher in Blood on the Tracks, too. While not supernatural, one can argue that Seiko and Seiichi mutually haunt each other. They flirt with madness by not wanting to disturb the waters enough to drive each other away. There’s a sense of inevitability to their actions that promises irreparable fractures in their psyches, all conducive to tragedy.

Blood on the Tracks coats its unique take on human horror with a blend of social worries and parental anxieties that question the very decisions people make when they choose to start families. It’s careful not to demonize anyone involved, as both Seiichi and Seiko can be taken as victims of a system that only concerns itself with producing more of the same small units of people living under one roof even when reality exposes how illogical the exercise can be. It disturbs, it unsettles, but it also asks questions we should all consider when deciding whether we should bring kids into this world. Especially given the capacity we possess to break their spirits.