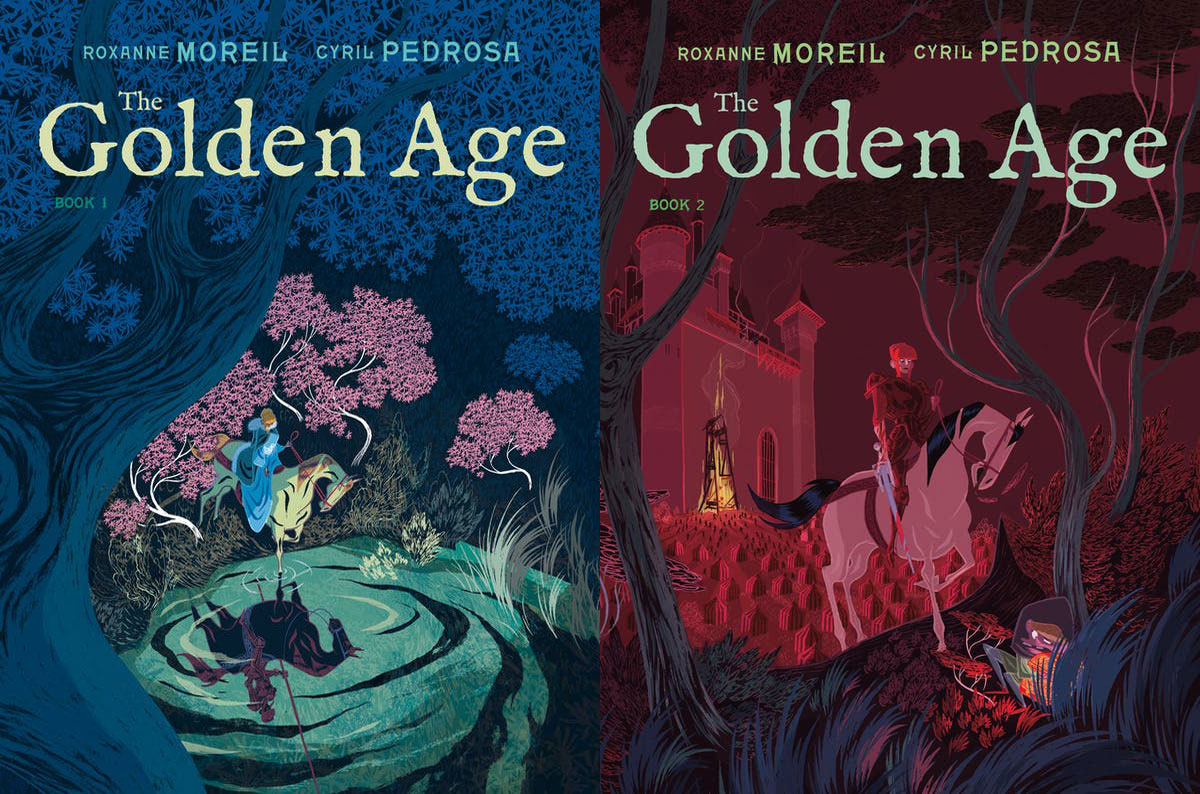

The Golden Age

Writers: Roxanne Moreil and Cyril Pedrosa

Artist: Cyril Pedrosa

Translation: Montana Kane

First Second Books

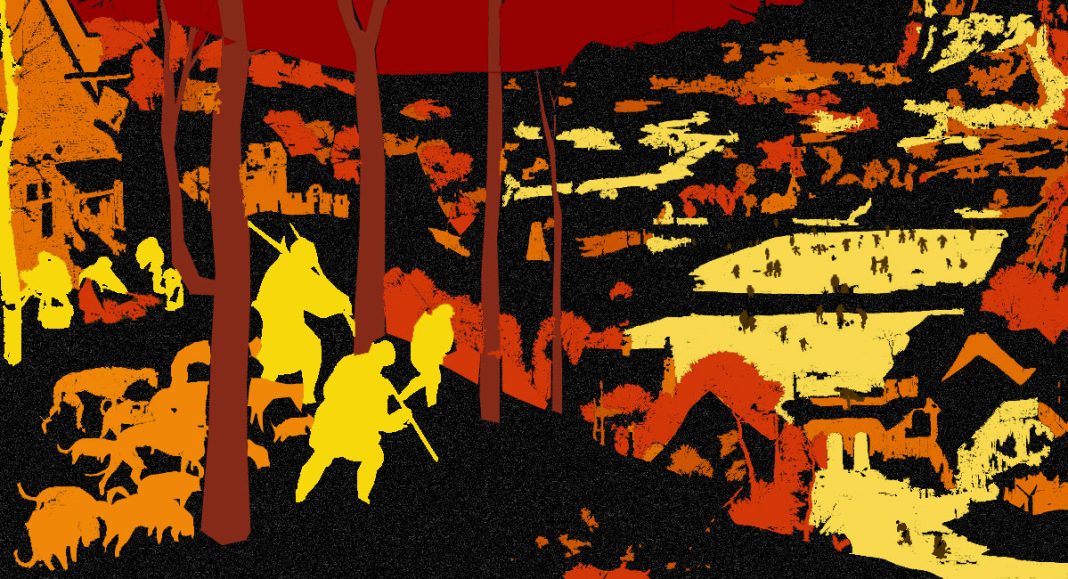

Cyril Pedrosa’s artwork embodies the approach he and Roxanne Moreil put into every aspect of their magnificent two-book series, The Golden Age. It isn’t, but it is; it’s post- while embodying the thing itself. Pages look like hand painted cel animation in their colorful layered execution and their vintage heroic romance aesthetic, strictly last century’s Disney, built from the same stuff as the classic style rather than upon it. Strikingly reminiscent of the fairy tale cartoons of my youth, but rococo to the verge of madness, and unlike any other books I own, really. Clearly not a lost tome, though the quality of craftsmanship does make it look of another age. The pen is Cyril’s and it is now.

The story Moreil and Pedrosa tell of a righteous kingdom deposed defies and adheres to chivalric literary tradition. Having understood and mastered the essence of the genre, they push what it can do out into contemporary emotional territory. Armored princess familial curse. Lost in the deep forest of today.

I was actually kind of surprised and delighted when I opened up a book that I figured would be playing on medieval Romance and instead found myself reading a story like The Hidden Fortress or Dragon Inn, an old dog warrior keeping the young rightful monarch from being executed by the wrongful one by secreting her away from her home. There’s even conscripted peasants offering their (justified) opinions from the edges. Leaving the castle behind in this way pops the fairy tale bubble. There’s no sanctuary cottage in the woods to find safety in; the wider world is as full of trouble and murder as the line of ascension to the throne.

The war for power might be driving the story, but the war against the powerful is consuming the setting the story exists in. Like the books’ heroine, Tilda, Nausicaä is another contemporary knight who fought for the world in the face of power, and like her manga, Tilda’s Golden Age rises and changes tone as it goes on to address the complexity of war, the real cost of life paid in pursuit of power, elegantly and with pointed meaning.

Where fairy tale and folklore overlap invariably leads to class consciousness. A single parent marries another single parent but there’s only enough for one child — coincidentally, as determined by the richer of the two parents, the child of higher station. The other is banished to the wild beyond the walls of home. It can happen to peasants without enough food, and it can happen to royalty without enough swords. The warrior with allegiance to the good and lost aspect of a troubled kingdom takes the role of guardian so that the princess can flee their war-torn land with her life. Though she is surrounded by vivacious and storied companions, life outside the castle walls is dire, feathered with arrows, and confirms for the princess that the change she wants to see is worth fighting for.

The antiwar realism in the world of The Golden Age is way more on the Akira Kurosawa side than King Hu’s, bordering on Gillo Pontecorvo once the second book gets underway and it’s armies doing the killing rather than family. The princess isn’t locked away in a tower, as she undergoes a perilous journey of exile in which the living conditions of paupers and peasants is truthfully depicted: starvation, mutilation, execution, conscription. Barred from her home, Tilda experiences the harried wartime conditions so many of the powerless have no choice but to endure, hunted and wounded. She was on the run because she was on the side of the oppressed. However, Tilda’s real spiritual awakening isn’t being exposed to the idea of injustice; it’s surviving the violence inequity causes.

While the first book largely reminded me of Asian storytellers, the second brought the story firmly back to the realm of its Arthurian aesthetics. There is a flash of lightning, a cliffhanger (all the more surprising as a Dragon Inn/Hidden Fortress style story would have wrapped up where the book was leading), and upon returning to the second volume, a total betrayal of all character expectations so that a parallel postmodern Grail Mystery retelling can spare the horses and save the kingdom.

Allow me to explain. Mystery get capitalized because it’s a type of story cycle. A ritual of rebirth and combat many heroes of legend have undergone. The king is sick and the whole land wastes away from the loss. The knight errant finds the font of abundance, the unquenchable cup, and their righteous action with it restores the monarch and the country. In The Golden Age, it is a spiritual stain more than a physical mark (though she’s got one of those, too), but that is the exact type of need that a magic goblet is best suited to sate.

The schism is the divorce between the symbols’ original meaning and the warped modern world. Knights and kings are projections of righteous power, but in practice? Historically the powerful are more known for subjecting populations to their will than liberating the oppressed. So if you want to tell a story that resonates truthfully to the experience of your readers but still remains faithful to the source material, it seems to me you have to create a world where someone who can never make the wrong decision is in charge and life totally sucks for everybody. Which brings it back around to contemporary influences like Pontecorvo who glorify resistance rather than lionize imperialism. The righteous fight the powerful, and kings, soldiers, and rebels alike prove their worth rather than rest on it.

Here I’m thinking about T.H. White and The Once and Future King. War sucks and power corrupts, the magician strives to teach a righteous king to actually experience how bad war sucks rather than just think about it (can’t do that from up on a horse telling other people to go get killed for your cause, gotta get down on the ground and assume the risk you ask of others to know what you’re truly asking), and tragedy ensues. Time and religious influence have rewritten the Round Table stories so that the wise king no longer makes the right decisions, the decisions are right because they were made by the wise king. Authors like White, Moreil, and Pedrosa are the fight against might equals right. How are monarchs supposed to rule justly when their wars mean the death of thousands of innocents?

That was the real shock of the second book: not the jump in time that keeps the incredible discovery at the end of the first volume enshrouded in mystery, but to see Tyrant Tilda a haunted shadow of her former self, poisoned in body and mind. She is not smaller; she’s full plate armor keeping the monster in as much as the arrows out, and set jaw neck stress, and dark circles under her eyes. She’s traded being chased for her life for the martial brutality of siege warfare. The suffering that she underwent from the machinations of the powerful lent legitimacy to her place as a representative of the downtrodden. So what the hell? How did Tilda become the ruler whose sickness brings suffering to her land, she’s still trying to depose the despot. Who then is the innocent who can heal the kingdom?

It’s the mix that sends me. Moreil and Pedrosa have taken the iconography of another age and philosophically moved it into ours, which made the symbols contradictions of themselves (a wicked king) that, now reversed, fulfill their purpose as originally intended. Forget for a moment kings and knights. The Holy Grail. An icon that brings plenty where there was squalor. The cup from which all may drink and never goes dry, the plate from which all may eat, the endless knot in the tarot, the Earth. In the world of The Golden Age, it’s anarchism. In Tilda’s kingdom, where starving folks are hanged for sharing in the abundance of the land– where they live, the earth they tend– because the landlords raised walls around what was once held to be a common treasury for all, the inequitable divisions created by power won’t be toppled by passing control from the wrong person to the correct one. Tilda’s righteousness returns when she dedicates herself again to the good of the people not the good of the monarch. A fight against the king, where the victor is prosperity shared so all may flourish, not by decree or demand, but because everyone alive deserves agency.

The story is a wicked blend of historic, postmodern, and cross-genre sources put together to present a contemporary critique of war, and the storytelling is just as sophisticated. The Golden Age is enchanting: the reader is grabbed by the art, drawn in by the story, and carried away through the both of them by the flow of sequential storytelling. Earlier I compared Pedrosa and Moreil’s story to the works of a few directors– their collaboration telling it visually can also feel quite filmic. Pacing that uncouples the panels (if they appear at all) from their job of dividing moments in time, and instead they use them to create physical movement of perspective that pans and zooms in service of emotion.

Two page spreads on large pages, turn the leaf and the camera has panned right to another two page single frame multiple exposure image. A tremendous amount of land can be captured in the deep focus of these frames. Wide far shots riding horseback through the mountain woods. Dialog happens over the distance traveled across the page, Bil Keane’s beloved dotted line method without the actual dotted line. The panels come in square and faster while navigating a castle or town destination, a succession of small environments, a series of accordingly-sized snapshots of secret library meetings or watching the moon from a window instead of a field. A conversation comes to a close and the eye of the camera zooms out and travels away, gutters recede, panels expand, and the moment is given space. The simplicity of it and its effectiveness bring to mind early innovators in the craft of cinema like Jean Renoir. It’s a dense book to work through, mentally and visually, but the finely-honed flow of the story bears the reader effortlessly through.

To read The Golden Age means to travel through several layers of “not of this time.” Pedrosa creates with classic Disney animator chops (literally) that extend far beyond nailing the Sleeping Beauty look. You could go after these books with a jeweler’s loupe and find the tiniest horses in print making their way along the same path through the whatever as the other iterations of the questers that are visible to the naked eye, marked together in color or found at the end of a word balloon tail so that the eye travels with the time and distance in the story instead of searching for characters in the trees. Big and close is used incredibly judiciously, but big and lots comes often. The vastness of the legendary forests that predate modernity are matched by humankind only in the construction of battlements and towering stone walls. Or within the four chambers of their hearts.

Pedrosa’s inseparable line and color also has that old school animator feel. The multilayered single subjects, be they characters or settings, look like overlaid cells done in paint much more than the line art on paper look that defines most folks’ expectations for comics. However I imagine an intensely modern art making process, layers and layers and layers in a digital editing program, each with their own internal color key, each a swatch on digital glass, a virtual stack when compressed and finalized, evoking something just as vintage as plate print process. The color combinations beguile when examined alone, though they are equally overwhelming when so impossibly laid upon each other to make panels pages chapters.

Yet it works as a read. There’s chaos and more, and there’s infinitely ornate beauty everywhere that makes you want to stop reading and simply comb the page for texture as you ride as swift as horses to the story’s end.

Published by First Second Books, The Golden Age graphic novel series is available now.