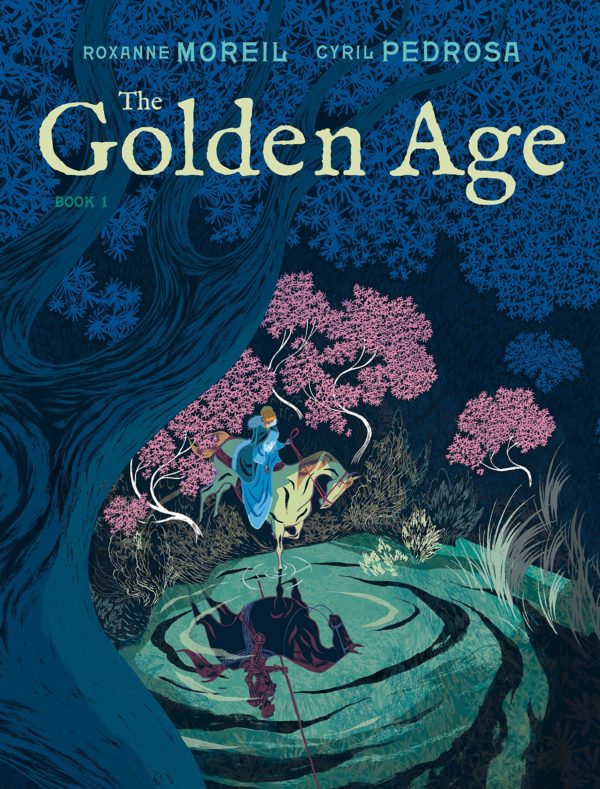

The Golden Age Book One

Written by Roxanne Moreil and Cyril Pedrosa

Illustrated by Cyril Pedrosa

First Second Books

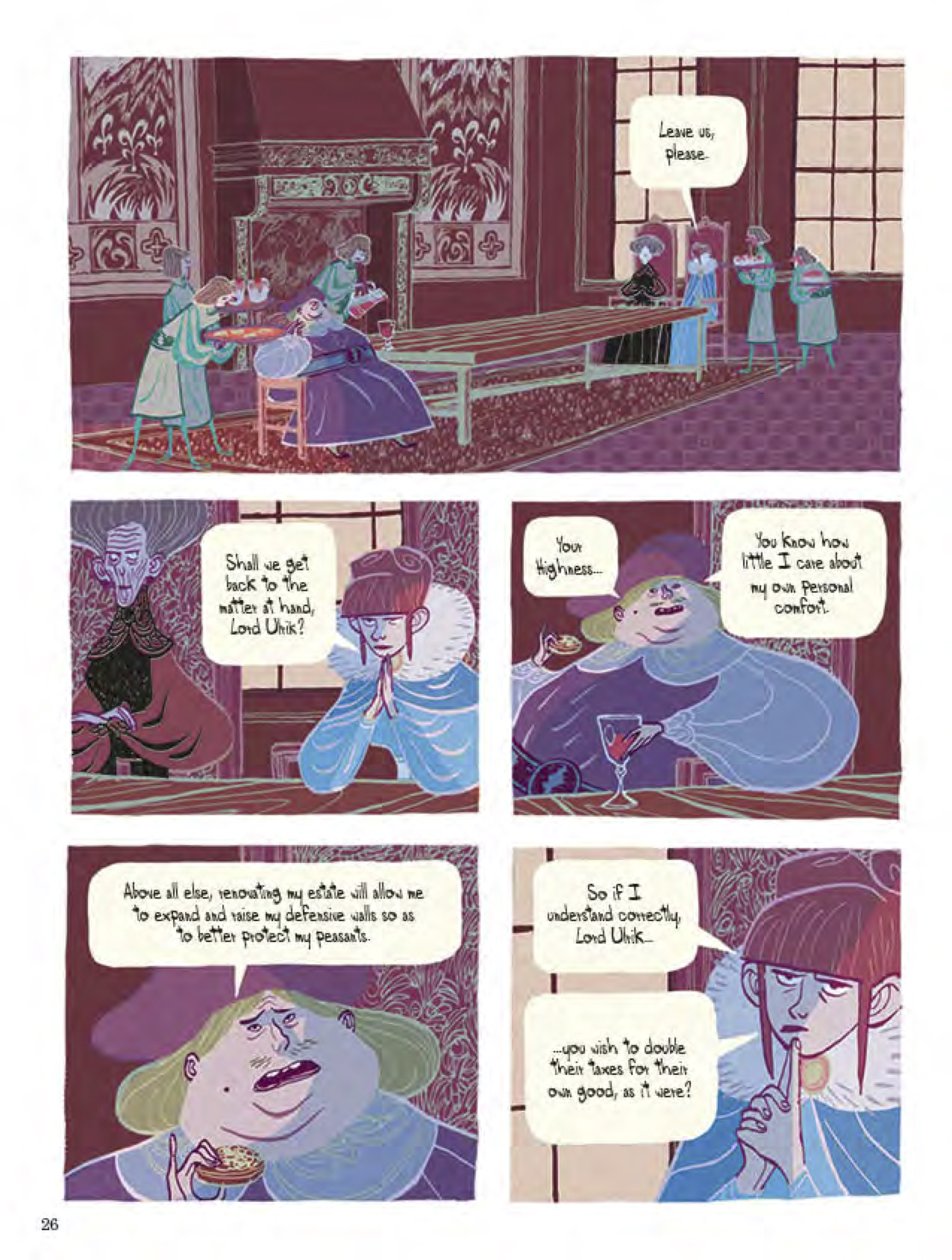

When King Ronan of Antrevers dies, his daughter Tilda imagines herself to be his heir, and as events move toward her coronation, she develops her benevolent plans for her subjects. But there’s a group of insiders who have different plans and gather around her younger brother to seize control and send her fleeing into the wilds of the kingdom in order to plot a seizure of what has been stolen from her.

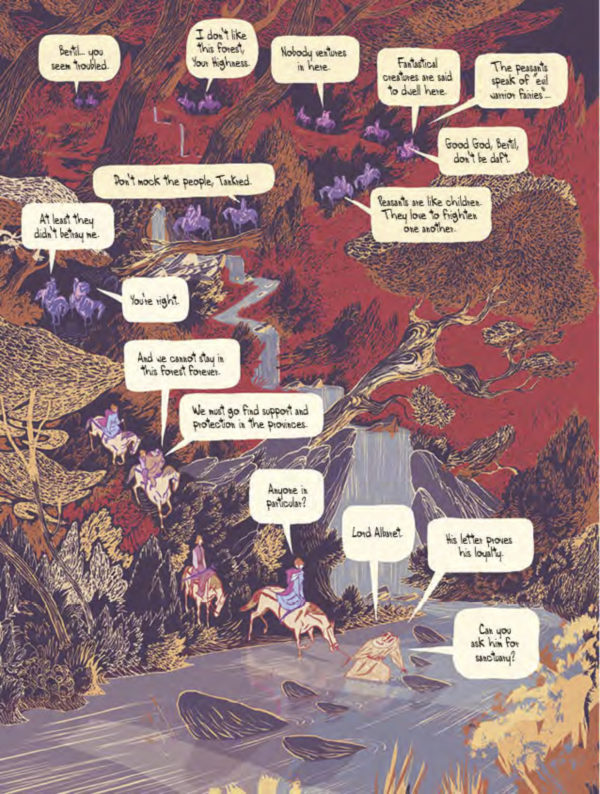

As fantasy stories go, the basic plot of The Golden Age sticks to the tropes, but it’s in the details that it steers into exciting territory. As Tilda moves further in her journey, she’s accompanied by the knight Tankred and his assistant Bertril, finding refuge in a community of women who have cut themselves off from the kingdom in order to find the peace and equality that they have been deprived of in their lives. This community provides a respite for Tilda to heal her wounds, but also to plant some subversive ideas into the story and, most importantly, Bertril.

In this fantasy world of Antrevers, there is a hidden past of an almost communistic flavor where all was shared and everyone was equal. It’s documented in a rare book called The Golden Age and the knowledge of it is passed through word of mouth, though those in power, all levels of it, work to suppress common people’s knowledge of it in order to push the idea that the class system is just a part of natural life.

But it’s this system that gives Tilda her mission to save the land from her brother and his conniving conspirators. That’s because she accepts the price of the class system, the responsibilities of it, as well as the benefits, while her brother and those who surround him ignore that side of their placement. Without the system, Tilda lacks structure. But if aspects of a system are so casually pushed aside in order to allow abuse, does that mean the system needs to be reformed or torn down? And can Tilda survive without the system?

For Bertil, there might be a third way, one that takes the responsibility of the system and channels it into something that both tears it down and builds something new and more fair. Among the qualities that makes The Golden Age stand out from so many of the fantasy epics that have become trendy in our post-Game of Thrones landscape is that it takes its hero, Tilda, to task when faced with the reality of the anger that lack of equality within the system has garnered. So accustomed is she to solving problems by embracing her status and the accompanying responsibilities as the natural order of things that she can’t break out of the mold easily when confronted with a radical possibility.

But Tilda is going to face her own radical revelation even if she shuns the other. As a woman in a system of power dominated by men, she is discovering her place within it. But she is a young woman and hasn’t yet considered how those in her position have previously existed in the system, nor that their end goals could be either in conflict to her own efforts or somehow gaining advantage from them for their own purposes. The powerful stick together until they don’t. The powerful always screw over the weak but nearly as often screw over the powerful in order to get what they think is theirs, and this is the radical revelation that Tilda has to face.

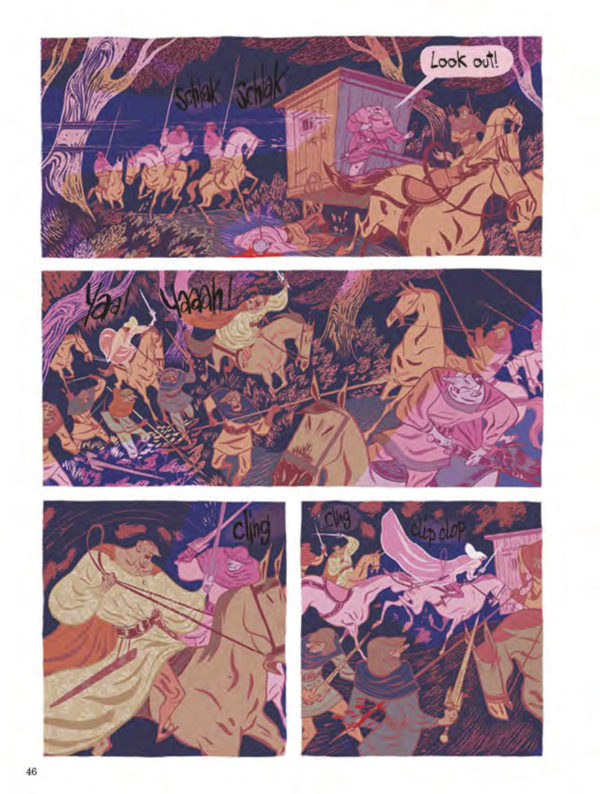

The Golden Age is a book that weaves in complicated concepts and asks big questions but doesn’t skimp on the tension of being thrust into the middle of chaos. As Tilda and her cohorts traverse the kingdom in search of the means to help their retaliation against her brother and also try to escape their pursuers, they fall into a country falling apart as the anger of peasants begins to escalate into a full-blown rebellion during the transfer of power. Danger is everywhere and political priorities are changing.

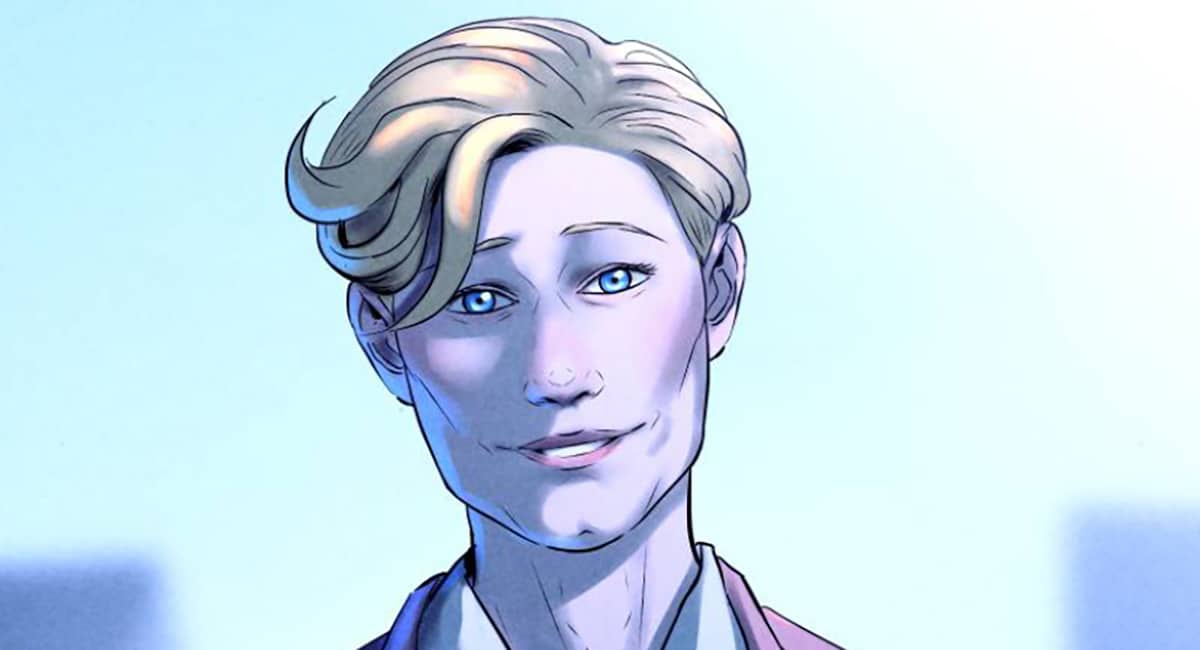

This is Moreil’s first graphic novel, written in collaboration with Pedrosa, and it’s an exceptional beginning, with Pedrosa’s illustrative work achieving the impossible by triumphing over anything he’s previously done. Pedrosa is typically lush and complex, but here he adapts his style with a fairy tale ambiance that embraces flatness with characters that evokes an animated quality but pushes them into intricate and sometimes surreal backgrounds that demonstrate clearly the situation they have found themselves in. The world these figures inhabit is dominated by off-kilter colors and meticulous textures within a sprawling design that defines every tree, every rock, every house, every aspect of the sky and atmosphere. It is overwhelming and dynamic, and it is bigger than any of them.

The Golden Age ends on a cliffhanger of possibilities and evolution. Moreil and Pedrosa seem to have crafted a fantasy epic that speaks to the classist inequality that burdens the world and fuels so much of the racism, sexism, and general hate that has overtaken politics. That they manage to do so while keeping a tone within the fiction that draws you in and doesn’t bludgeon you even as the themes unfold with the plot speaks to how essential this release is.