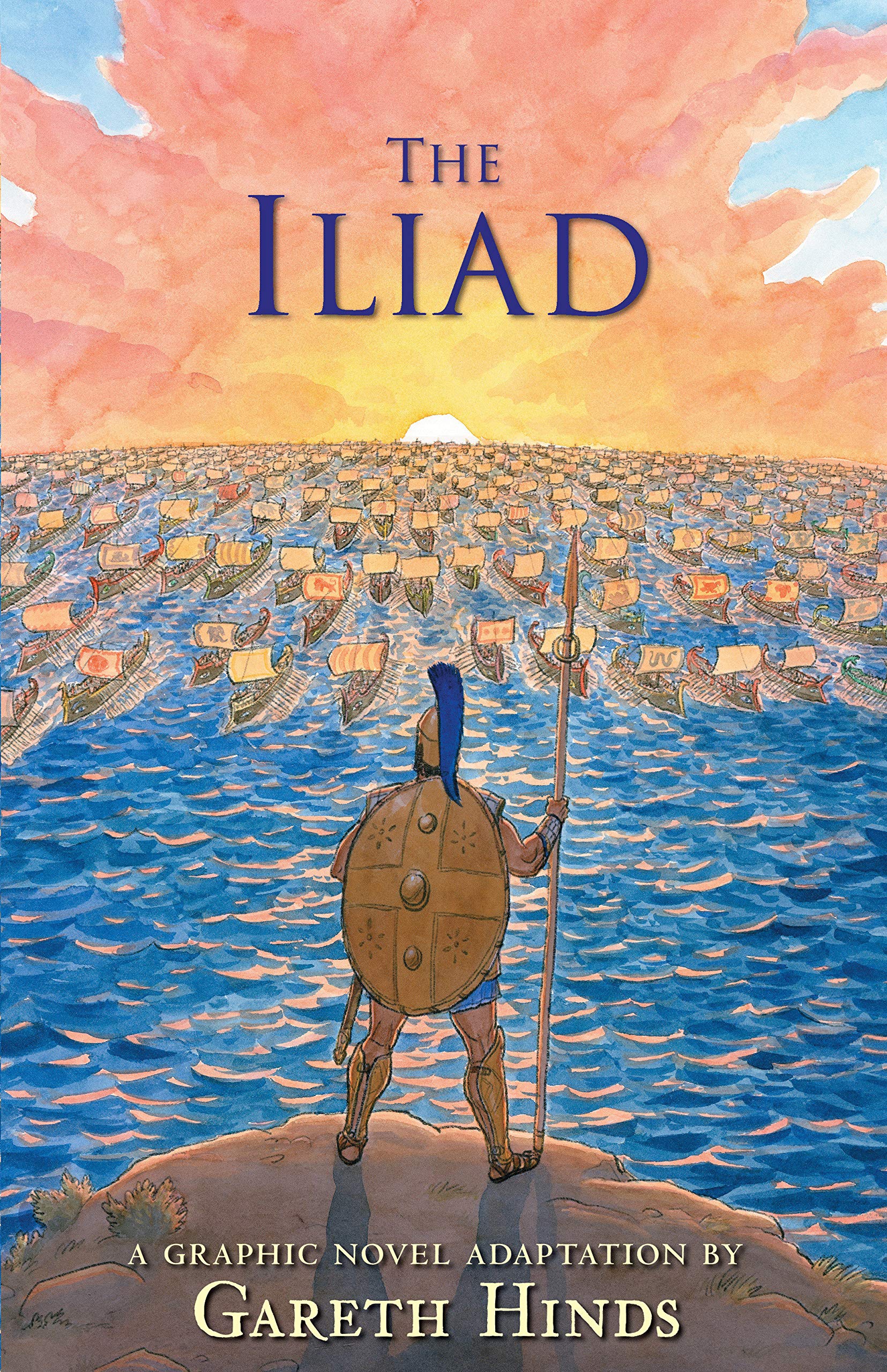

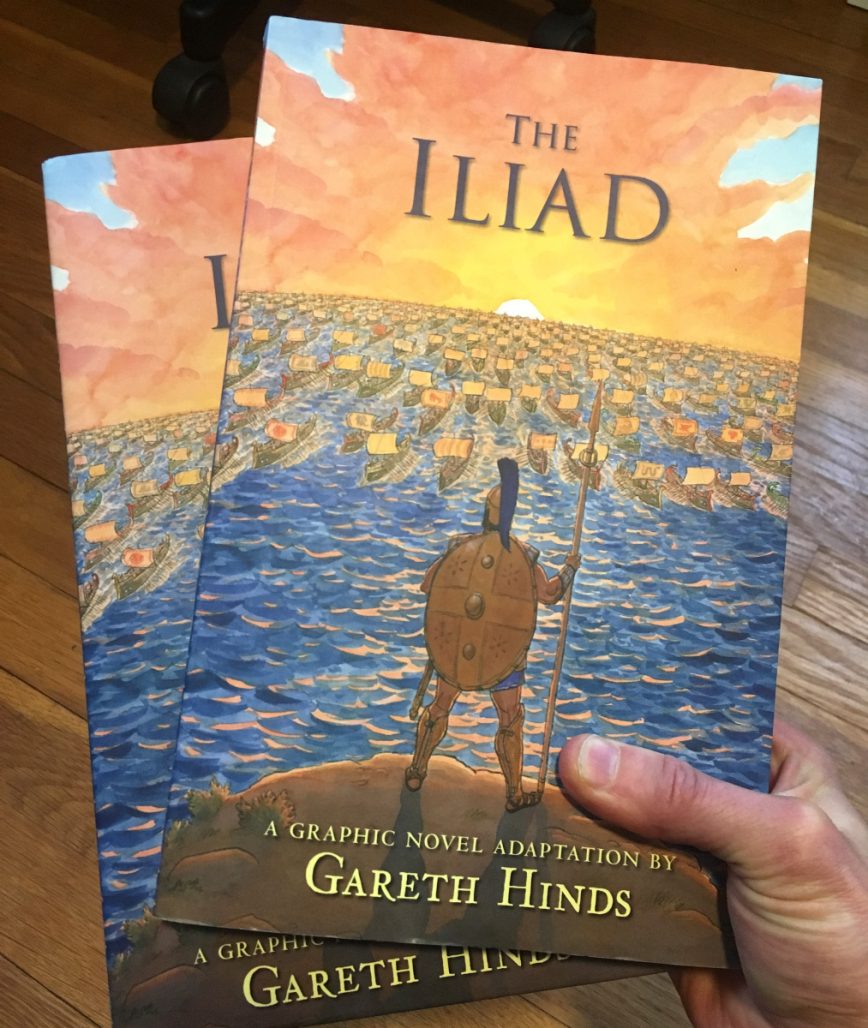

On March 12, Candlewick Press will publish Gareth Hinds’ latest adaptation of not only a classic piece of literature but a cultural staple, The Iliad. Through brutal and beautifully rendered imagery, the book adds a level of translation to the original epic dactylic hexameter of the story many years ago in ancient civilizations.

Gareth Hinds gave us an exclusive peek at his process that we can share today.

Today I’m going to describe to you how I create my graphic novels, particularly my newest title, The Iliad.

For most graphic novels, I can roughly summarize the process as: outline, script, design characters & settings, draw rough sketches of the whole book, edit, draw final art, color final art, make final edits, deliver.

In this case, I started by (re)reading the full text in several translations, including Fitzgerald, Fagles, Rieu, and Lattimore. I also read works like Virgil’s Aeneid, Quintus Smyrnaeus’ The Fall of Troy, Herodotus’ Histories, etc., which help fill in details about the characters and important events that inform our understanding of The Iliad and what happened before and after the Trojan War.

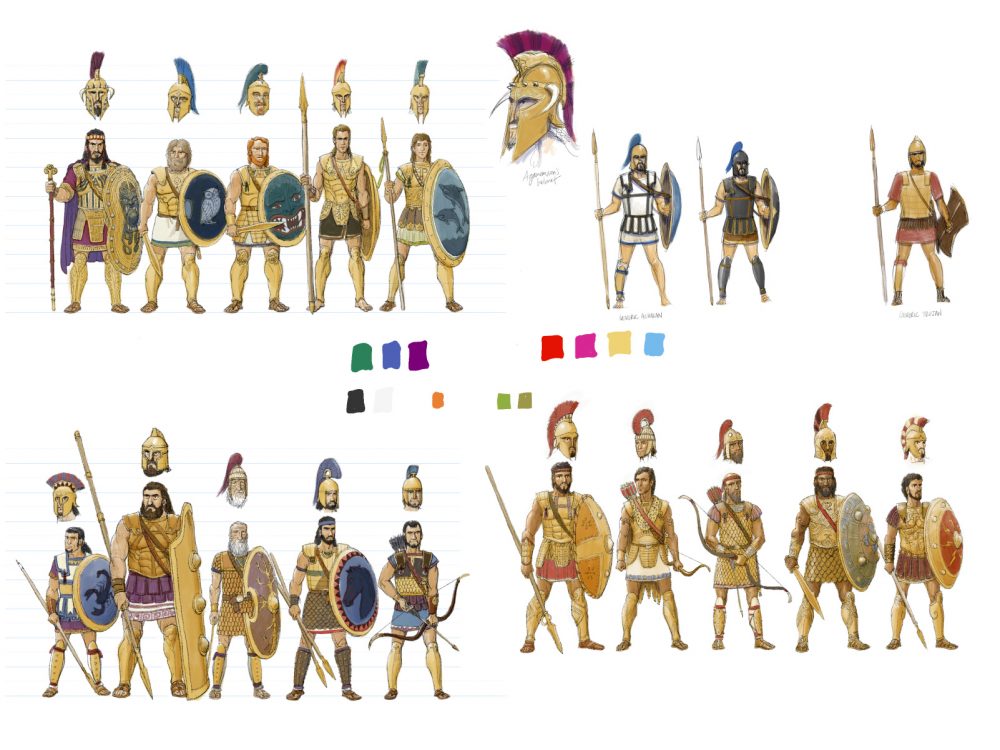

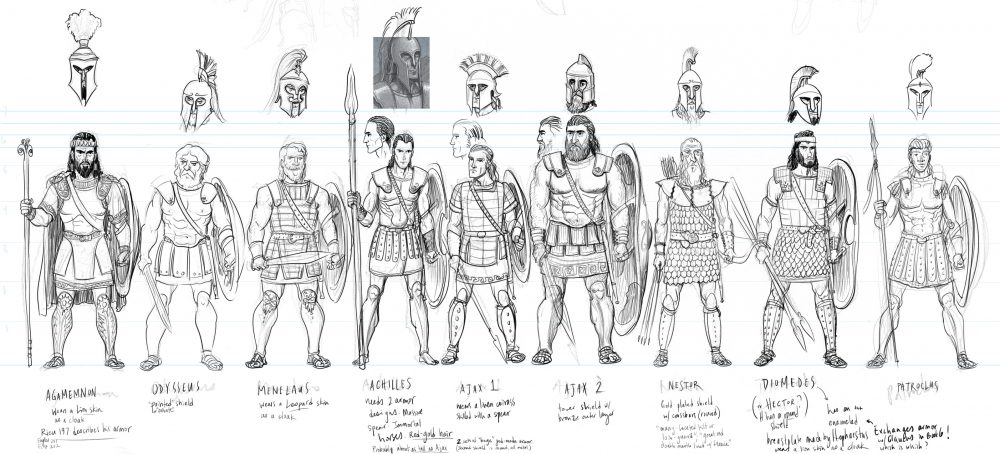

As I was reading, I started drawing character sketches for the Greek and Trojan heroes. My goal was to make each hero distinctly recognizable and capture something about their personality. I felt that was one of my main jobs with this book, helping the reader make sense of the large cast of characters. I experimented with using colors, shield and helmet designs as well as body shape and facial features to accomplish this.

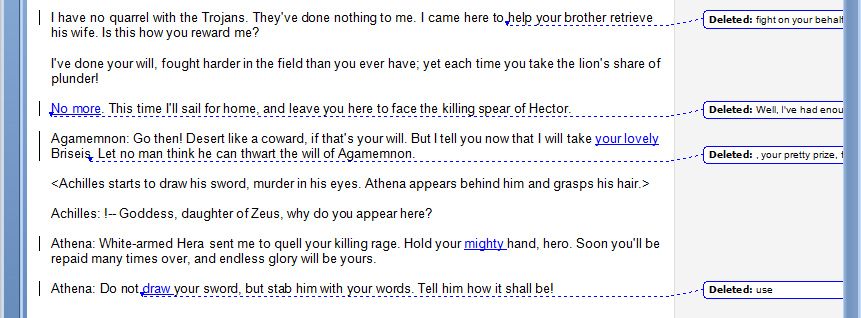

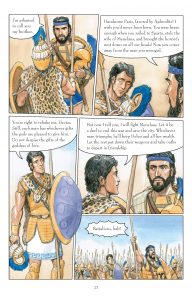

Next I wrote the script. I re-read each scene in at least 2 of the 4 translations, then rewrote it, trying to capture the flavor and rhythm (but with a lot less words). I quickly found that the density of information is so much greater in The Iliad than in The Odyssey, that I had to break my usual rule of not using third-person narration. There’s just too much to convey, and much of it is the kind of information that can be communicated more efficiently in words than pictures.

[fig. 4]

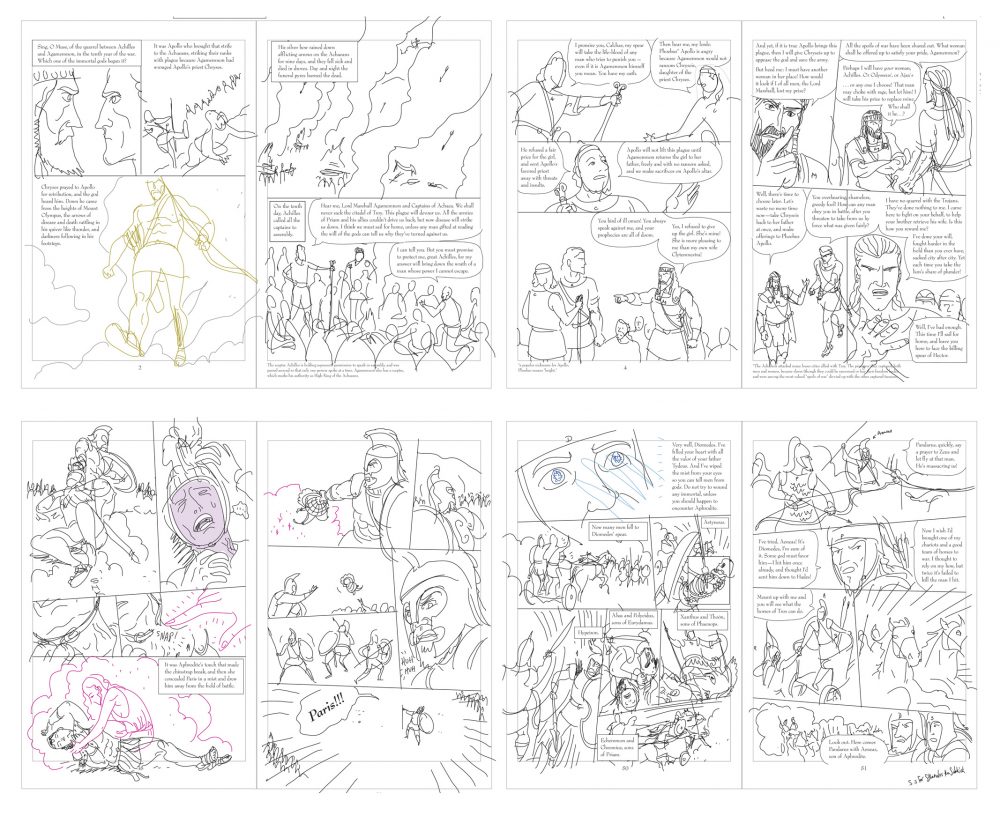

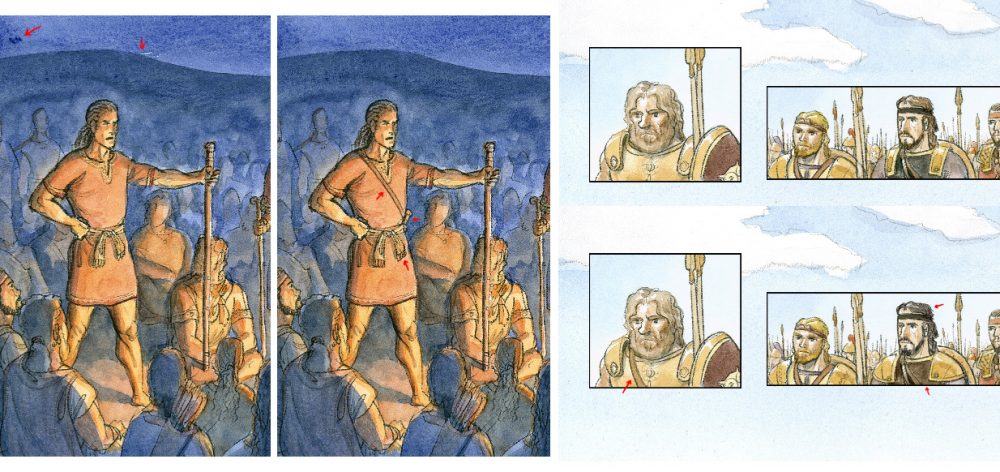

Once I had a rough draft of the script, and had designed the main characters, I started sketching the rough layouts. I do this in Adobe InDesign using the freehand pencil tool. This lets me group lines into elements, move them around, scale them, and generally tweak all the compositional elements that make up a page. Storytelling in comics is all about the choice and placement of text and images on the page — the juxtaposition of the elements is what creates meaning and tells the story. Here are some examples of what those rough sketches look like.

The reason to do the whole book in rough sketches is so I can experiment with multiple options quickly, and then get editorial feedback and make changes before I draw the final art. That’s super-important. Huge thanks and kudos to those to read this monster of a book and gave me feedback — especially my editor Carter, my “in-house editor” Alison, and my scholarly reader Stephen! The feedback at this stage was mostly about pacing, page composition, drama and clarity of storytelling.

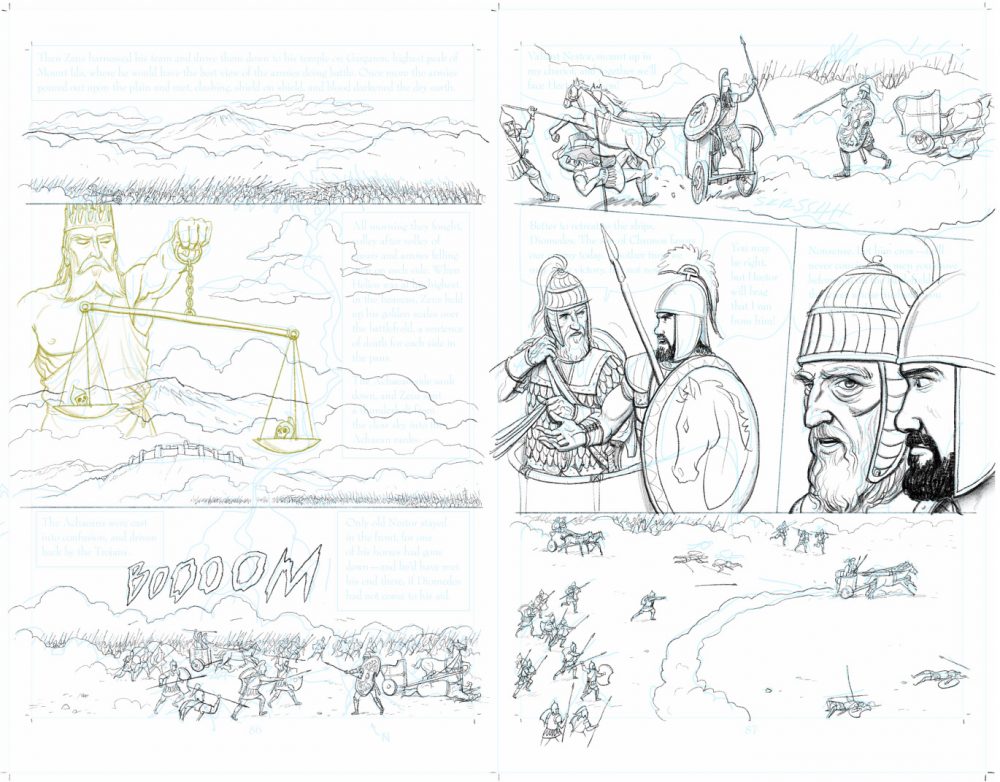

After revising the rough layouts, I drew the final line art. I experimented with drawing in ProCreate on the iPad pro, and found the results almost indistinguishable from real pencil, while offering the advantages of being able to draw on multiple layers, to erase cleanly, and to “undo” clumsy lines.

I got more feedback and made another round of revisions to the line art. The feedback here was largely about clarity of action and consistency of facial likenesses. At this stage I also wrote the author notes (and then with some difficulty edited them down from 20 pages to 11. There was, and still is, a lot I want to say about this book!)

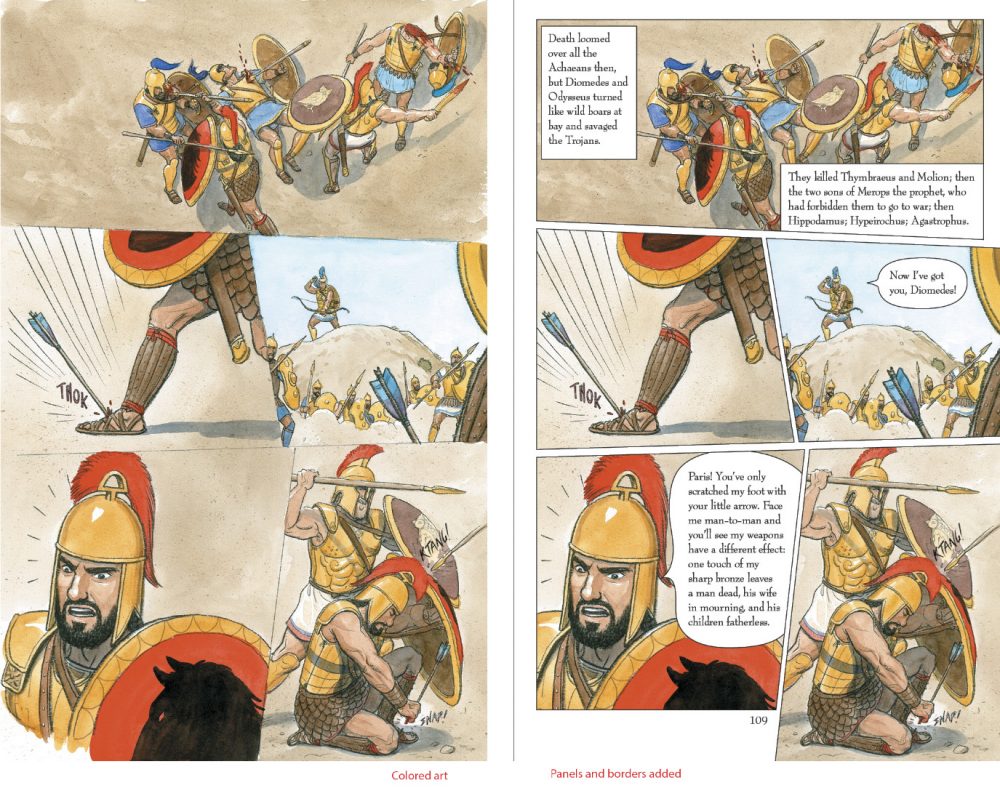

Using an inkjet printer with water-resistant inks, I printed out each page on 10×15″ watercolor paper. That’s about 140% of the size of the finished book — most illustrators work at a larger size than the art will be printed, as this tends to tighten up the look of the artwork. I then painted each page with watercolors, then scanned it back into the computer.

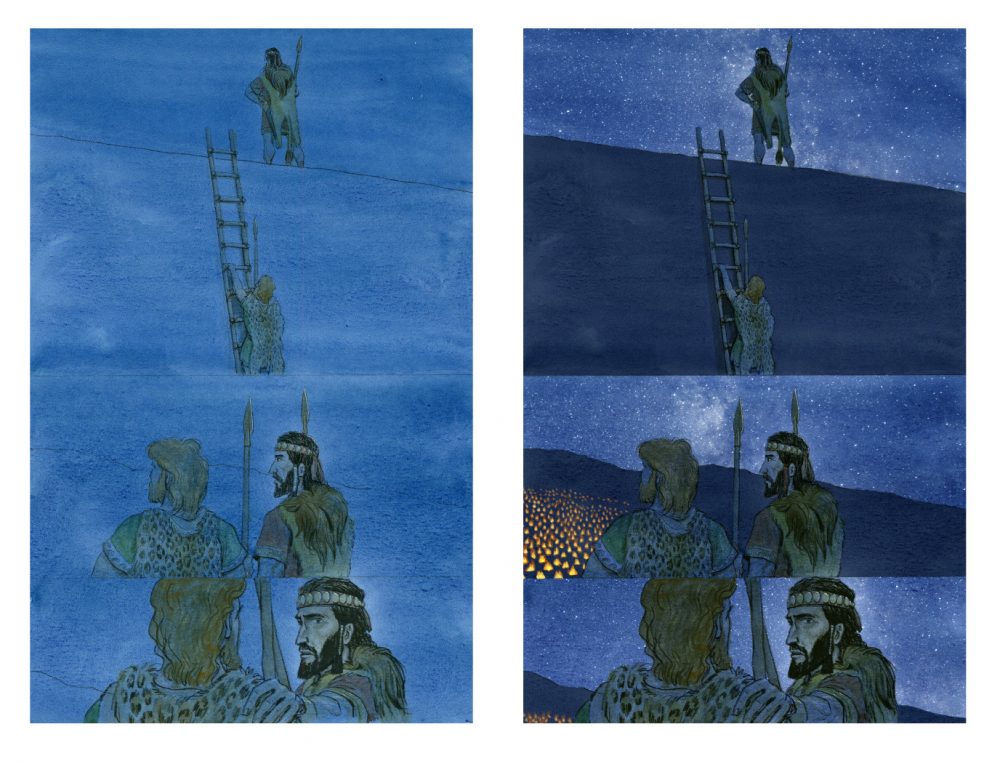

On problem I’d had on The Odyssey was that the dark nighttime scenes tended to get blotchy when I painted them with watercolor. I was able to get the effect I wanted more easily in The Iliad by painting those scenes lighter and then adding more layers of color in Photoshop to darken them to the tone I wanted. I was pleased with the rich colors and even textures I was able to get this way.

I also added sound effects on separate layers in Photoshop, so that they can be easily replaced if the book gets translated into another language.

Finally, I added the panel borders and cleaned up the speech balloons.

I had a few days to read through the whole thing and fix any glaring issues I found. Then on the agreed-upon delivery date, I sent the final files went off to Candlewick… along with a very long list of additional edits I wanted to make.

While I was waiting for Candlewick’s feedback, I went ahead and fixed every mistake I could find. I did a full “continuity pass” where I tracked each character through the book looking for panels where a shield-belt or sword hilt changed. There are something like 150 named characters in The Iliad, of whom about 45 are important to the story, and each has a shield, shield-strap, sword, sword-belt, helmet, breastplate, tunic, belt or sash, etc. — and each element needs to stay consistent ! Here are some examples of the digital edits I made at this stage. Most of these are done in Photoshop, though in a few rare cases I drew or painted a replacement panel or character.

Candlewick got back to me requesting a few more changes and giving me a new really-final deadline. I pulled an all-nighter to deliver the final edits at 5am on March 12, 2018, and felt a large weight I’d been carrying for two and half years finally lift off of my shoulders.

The canny reader will notice that date is exactly one year before the date the book goes on sale. Books typically take about that long for the publisher to produce, because they have to go through a lot of hands. Some of the things that happen in that year include copyediting; printing & checking proofs to sure the art looks right; creating a marketing plan; writing and producing marketing materials; listing the book in catalogs; getting thousands of copies printed in China and shipped over by sea; sending advance copies to reviewers and bookstore buyers; distributing the book to stores; and many more things behind the scenes. The author typically goes on to work on other things, and when the finished book finally shows up, it’s a pleasant surprise!

If you’d like to know more about my process, I’ve posted process articles and videos on my blog about previous books, and I will be posting more process videos for The Iliad in the weeks to come.

The Iliad comes out March 12, 2019, and can be pre-ordered now.

Thanks for reading!

- Gareth

You can also view Gareth’s process as he details even more in a video published on the creator’s channel.

This adaptation of The Iliad is the power of comics as a medium and you can read for yourself on March 12. Check out the preview below

THE ILIAD. Copyright © 2019 Gareth Hinds. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

I had already been interested in this comic book, but what a great description of process! Thank you for sharing, Gareth, and I’ll be sure to pick up a copy when this comes out. I never could make it through the original epic in text form.

Comments are closed.