With so much political rancor permeating American society, it can be (extremely) difficult to remember that the systems put in place are meant–at their best–to help the average citizen. Our representative government, though imperfect, is meant to reflect community values in the hope of creating positive outcomes for all. Of course, not every politician embodies these values; many lack the guile or altruism. For over thirty years, however, Massachusetts sent Barney Frank to represent them in Congress. Representative Frank, known for being curmudgeonly, a little sloppy in dress, and curt with both allies and foes, was also one of the most vigorous protectors of civil rights. Whether one can align their politics with Frank or not, he was an unlikely LGBTQ+ pioneer for progressive causes with an influence that is still felt today.

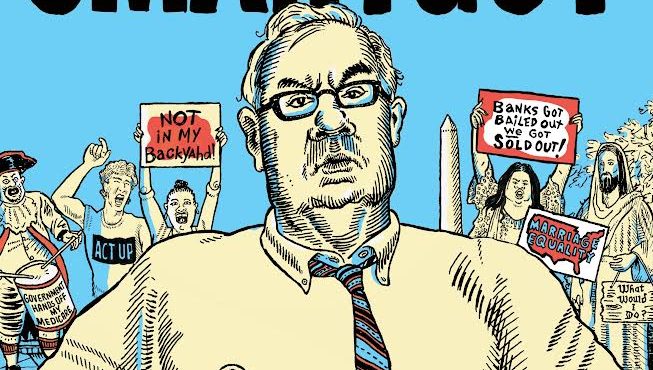

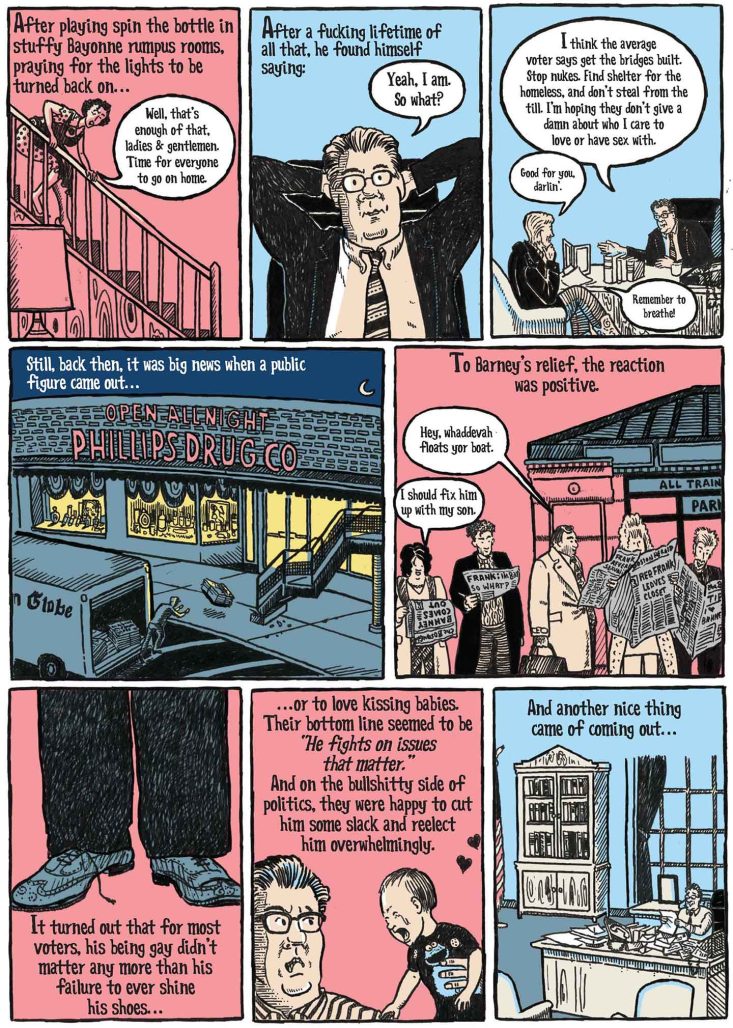

The recently-released Smahtguy: The Life and Times of Barney Frank by cartoonist and former Frank staffer Eric Orner (The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green) chronicles the life and career of Rep. Frank. A moving, funny, and inspiring work, Smahtguy doesn’t shy away from highlighting its main subject’s human foibles, nor does it retreat from displaying the razor sharp wit that Rep. Frank possessed (and so many of his colleagues lacked). I asked Orner about why he wanted to write this book, his influences, and what Rep. Frank’s career means for readers today.

AJ FROST: I wanted to start by asking about the inspiration for Smahtguy. I don’t just mean chronicling the career and life of Rep. Barney Frank, but what gave you the spark to write about this singular figure in American political life?

ERIC ORNER: Here’s what was going through my head, as a sort of first germ of an idea that led to my creating Smahtguy: I think Americans are accustomed to admiring outsiders and activists who agitate successfully for social change: Think Rosa Parks, Cesar Chavez, Harvey Milk. The thought I had was: I wanted to tell a story of someone working from inside the system, someone doing the unglamorous, often demeaned, work of legislating to advance American society in positive ways that included LGBTQ rights, voting rights for African Americans, elder rights, and affordable housing among others.

I’m a bit of a contrarian and the challenge of trying to interest readers who might be reluctant to immerse themselves in a story about political machinery, and the good it’s capable of, appealed to me.

FROST: In your opinion, what makes Rep. Frank a compelling subject for a graphic biography?

ORNER: I really felt he had a captivating personal story, in an anti-hero sort of way. He’s totally cast against type for an American politician. Gruff, unslick, too-honest for his own good, and not necessarily likable or handsome. And with a searing sex scandal at the midpoint of his life story.

FROST: Did you have any comic (or non-comic) inspirations as you wrote the book?

ORNER: My go-to comics inspiration for how to tell a story about politics in a way that engages people is Persepolis—about the theocratic takeover of a once-modern society in Iran. And I love the graphic memoirs/novels of Alison Bechdel, Mimi Pond, Rutu Modan, and Riad Sattouf’s masterful The Arab of the Future books. Also, I am inspired by the comics art of Ben Katchor, Lynda Barry, Emily Flake among (many) others.

A non-graphic fictional book that inspired me in creating Smahtguy is It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis. It’s about what happens when politically progressive folks spend more time fighting each other than right-wing reactionaries on the other side of the political spectrum, resulting in a marauding fascist triumph.

FROST: Can you tell me about your background working with Rep. Frank? What were your observations of him at the time you were on his staff and how were those integrated into the final version of the book?

ORNER: The book is not a memoir. I don’t play a role in it even though, in fact, I did serve on Barney’s staff for several years. But that fact, in of itself, never struck me as sufficiently interesting to base a book on. I wrote a book about Barney because I thought his story – and the story of American politics during the years he served—is interesting, funny, sometimes tragic, and I hoped it would make for a good read.

FROST: How long did it take you to create this book, from conception to publication?

ORNER: A year of writing—I write a script or really a screenplay first—and consider the drawing stage (which took three years) as akin to filming.

FROST: You depict the thrills of politics and the drudgery of public policy. How did you approach conveying these elements in the limited page space that you had?

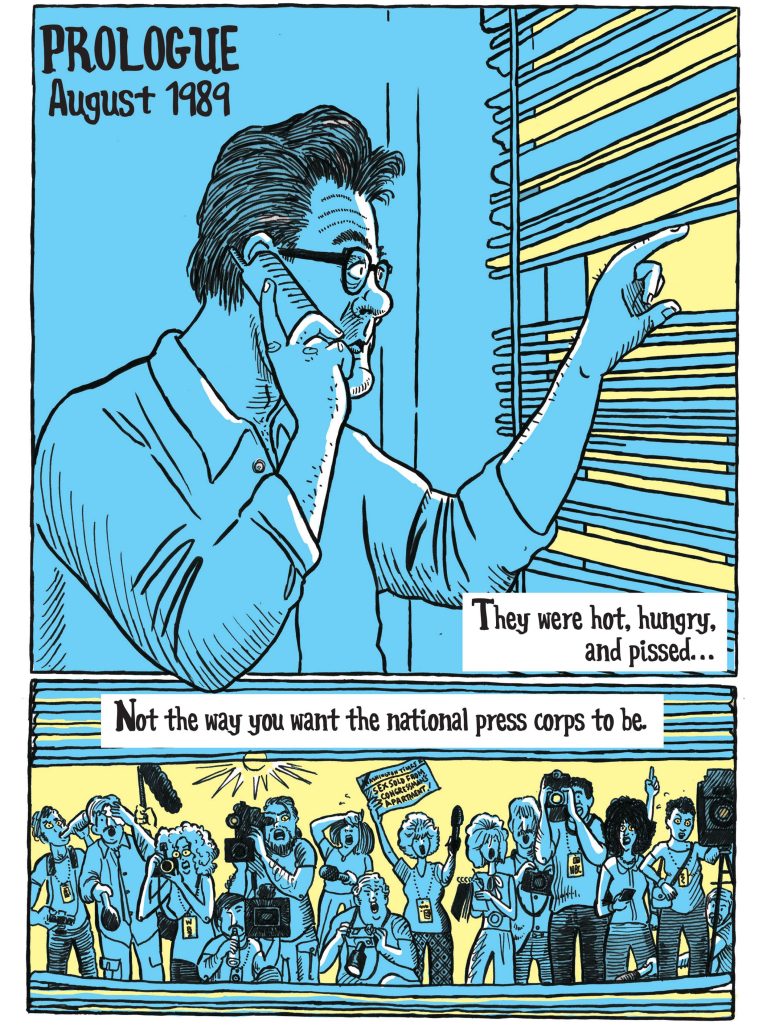

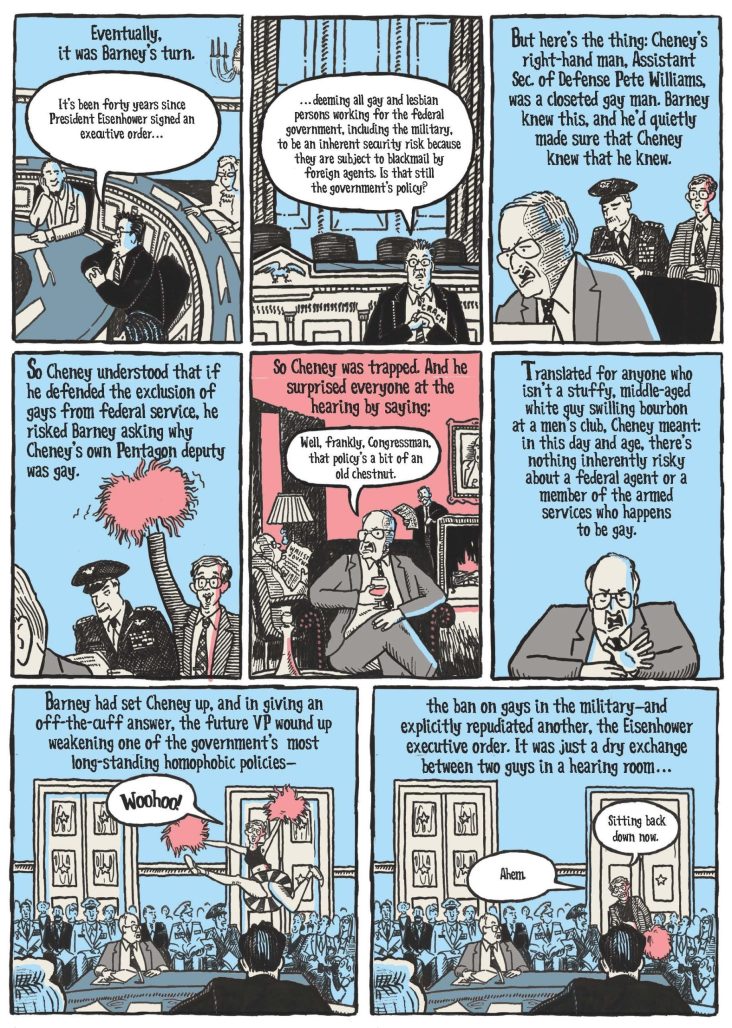

ORNER: I enjoy the pageantry of American politics: the rallies, the colors, the speeches, the hokey customs, though a lot of that is fading away in our era where social media dominates. That aside, I wanted to show the work of Congress as being full of drama—Congressional hearings during the McCarthy era, or Watergate, or when Anita Hill presented testimony of Clarence Thomas’s wholesale lack of fitness for high office.

FROST: Did you consult any of the existing biographies of Rep. Frank to assist you in creating this book (to create a timeline, fill in small details, etc.)?

ORNER: Yes, there are a few good biographies of Barney Frank, including his own autobiography, Frank. And another by Stuart Weisberg. I particularly liked Robert Kaiser’s Act of Congress, Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big to Fail, and the seminal Common Ground, about Boston in the 1960s and 1970s by J. Anthony Lukas.

FROST: How much of the book comes from your own memories or conversations you had with colleagues or Rep. Frank himself?

ORNER: My familiarity with the landscapes of Barney Frank’s life—Boston, DC, gay America (whether you’re in Boston’s South End, or the Castro, or Saugatuck, or WeHo or one hundred lavender points in between) helped me—I hope—bring these places vividly to life. However, the book’s essentially a biography, and for the specific details of Barney’s life—those I didn’t know or hadn’t been privy to—I did a lot of interviewing of him, of family members, of his colleagues.

FROST: And relatedly to the previous question, did you consult with Rep. Frank about this book? And if so, did he provide any feedback?

ORNER: Barney knew about the book as I was creating it—but it wasn’t an authorized bio—in the old publishing sense of a book where the writer and subject collaborate on a manuscript. My goal was to present Barney’s story, warts and all. Even though the book details his faults however, I think my admiration for the work he did shines through.

Barney had no veto over the text and didn’t see the visuals until the book was completed. I gave him the almost-completed galleys late in the production process, he read it and worked up a list of factual mistakes which I corrected.

FROST: What was the cultural or political context of this project? Do you feel that Rep. Frank’s career still has the power to resonate with readers even though he’s been out of public office for years now?

ORNER: Certain figures in American political life wind up having cultural significance that transcends their political importance: Think of John Lewis, Barbara Jordan, Bella Abzug, Mayor LaGuardia, Jeanette Rankin (who got elected to congress in 1916 voted against American involvement in World War I, was thrown out of office by her Montana constituents for her pacifist stance. She got elected to a second term 24 years later, only to find herself casting a vote in 1941 against American involvement in World War II, thereby losing her congressional seat once more, for the same reason). I think Barney’s role as one of the pioneering LGBTQ+ members of the U.S. Congress put him in this company.

FROST: Without intending to be so, Rep. Frank was (and remains) a LGBTQ+ trailblazer in the halls of power. How do you think his advocacy for basic human dignity influenced others?

ORNER: Barney was a tenacious fighter for progressive changes to American life, certainly for lesbian and gay equality. He introduced some of the earliest gay rights bills. But also, he fought for elder rights, consumer protection, and later for reigning in Wall Street greed and irresponsibility. I think his combative nature combined with his legislative skill inspired others to fight harder—and smarter—for justice.

FROST: Do you think he could have gone farther?

ORNER: He worked his heart out for every policy or legislative advancement possible. But he never believed in leaving three quarters of a loaf on the table, just because at a certain point in time there was no way of getting the whole loaf. He didn’t believe in letting the perfect be the enemy of the good. He left that to Ralph Nader, or the folks who refused to vote for Hilary Clinton and, in the process, handed the Supreme Court to conservative Christian fundamentalists. He felt that if people on the left and center-left didn’t find a way to work in concert, they’d wind up handing the reins of power to fascists.

FROST: Visually, the book is absolutely striking. What guided the bold coloring choices?

ORNER: One thing I learned in my days as a story artist at Disney and other animation studios is that color should be used to set a mood and advance the story. That was my goal when it came to the shifting palette of the book. So glad that you like the result.

FROST: For readers who may know of Rep. Frank, or have some passing knowledge of him from when he was in Congress, what do you want them to walk away with?

ORNER: I think a takeaway I’d like people to consider is this: Barney’s brand of politics stands for the proposition that to build a more progressive society, you need to be passionate and strategic.

FROST: What do you want readers who may have the opposite ideology of Rep. Frank walk away with should they read this book?

ORNER: He was blunt with those on the right about what he thought of their politics. But that didn’t prevent his willingness to work with them when common ground was identified. That’s how the pro-consumer Dodd-Frank bill –reigning in Wall Street and Big Banking–got passed despite a totally polarized Congress. Barney was good at seeing past the shouting (which he did plenty of himself) to see those many points in American life, where we actually don’t disagree with our neighbors.

FROST: Thank you for taking the time to chat.

Published by Metropolitan Books, Smahtguy: The Life and Times of Barney Frank is available now.