This week: This Doom Patrol: Weight of the Worlds #2 review dives into the book’s contradictory nature.

DC Comics is trying something new. In the wake of their Rebirth initiative, the publisher has rapidly expanded its content to include diverse new imprints such as Young Animal (redux!), Wildstorm, Jinxworld, Wonder Comics, Black Label, Ink, and Zoom. As their lineup expands, it can be hard to figure out what to pick up each week. That’s what our team is here to help with, every Wednesday, with the DC Round-Up!

Note: the reviews below contain spoilers. If you want a quick, spoiler-free buy/pass recommendation on the comics in question, check out the bottom of the article for our final verdict.

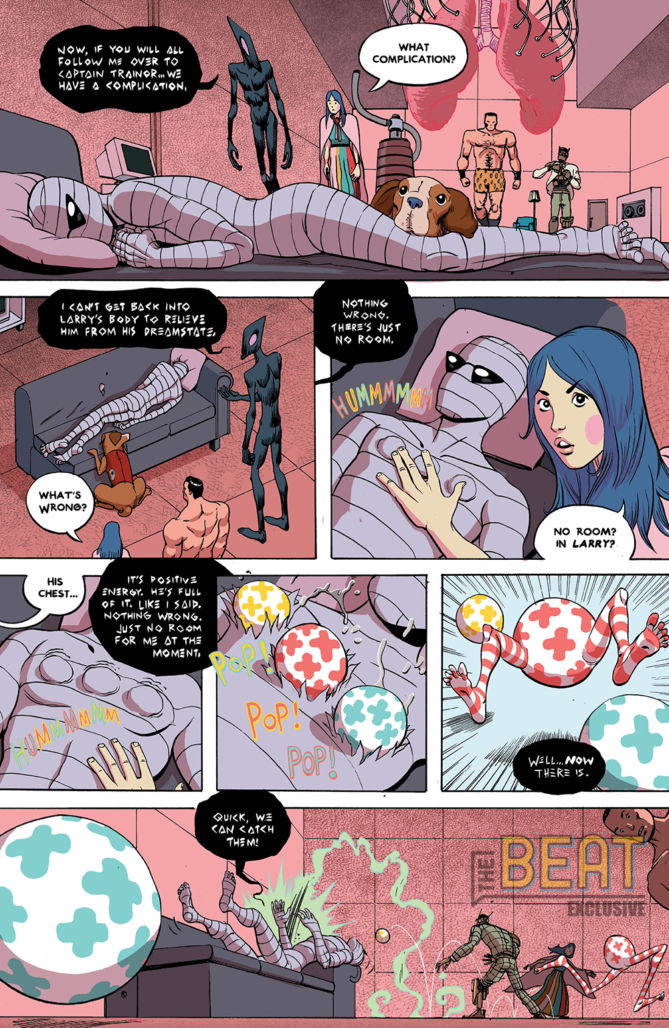

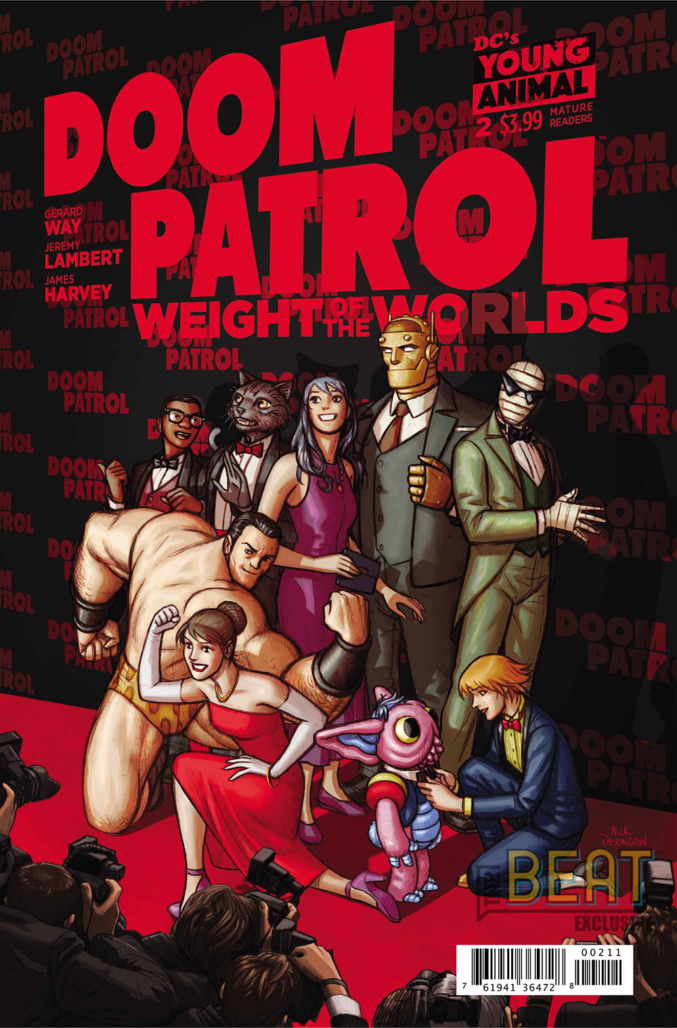

Doom Patrol: Weight of the Worlds #2

Writer: Gerard Way

Co-Writer and Assists: Jeremy Lambert

Artist, Colorist, and Letterer: James Harvey

A common quirk of long-running monthly superhero comics is the careful balance these stories have to maintain between rewarding to long-time readers and remaining accessible to new audiences. Indulge too much in continuity, and things become inscrutable to anyone without prior knowledge. Stray too far from established history, however, and the longtime reader base rallies in protest. The audience that will sit through six months for a complete storyline has dwindled, but is a mostly contained one issue story enough of a chunk to satisfy the reader? Navigating this liminal space is tricky at best — but it’s the position that Doom Patrol finds itself in as Weight of the Worlds continues with its second issue of mostly self-contained story.

The gambit that Doom Patrol: Weight of the Worlds makes is simple and, in theory, effective. While the original Gerard Way and Nick Derington run on the title stuck mostly to the multi-issue arc and single artist structure that most DC, Marvel, and Image comics follow, the stories told in Weight of the Worlds are mostly self-contained. A problem happens, the Doom Patrol arrives to help, things are resolved, and you get a brief cliffhanger that keeps you compelled to read on but doesn’t become the conceit for the next issue, necessarily.

Obviously, only two issues in, it’s early to say that this is a pattern Weight of the Worlds will keep as it goes on. However, as the series begins rotating artists — which it plans to do soon, one imagines the episodic nature of the title will become a matter of necessity rather than one of entirely intentional design — after all, it’s much easier to coordinate with one artist than it is with ten. The best thing to do when you’re working with many different artists is to limit the amount that any will have to coordinate story beats with one another. And so, episodic becomes the logical path forward. It’s not only simpler, but more accessible as well. Theoretically, you can pop in and out of this series like you used to be able to with most comics, knowing that any issue you picked up would give you a complete adventure.

Here’s the thing about Doom Patrol: I love this series and I love the property as a whole. I also think it’s pretty inscrutable, though. Even if you can buy that this world can have a man lose his body in favor of a robot one; even if you buy the transcendental cat person; what on earth is Danny? What is a Negative Man? I know the answers to these questions, but I’ve also read the entirety of this Doom Patrol run, as well as all of Grant Morrison‘s and Richard Case‘s run before it (I haven’t come across Rachel Pollack‘s, sadly). As loathe as it is to say, not many people have read this much Doom Patrol, and I think you lose something in a story like this if you haven’t. So you have this book — theoretically accessible thanks to its self-contained nature, but practically not due to its incredibly heightened concept.

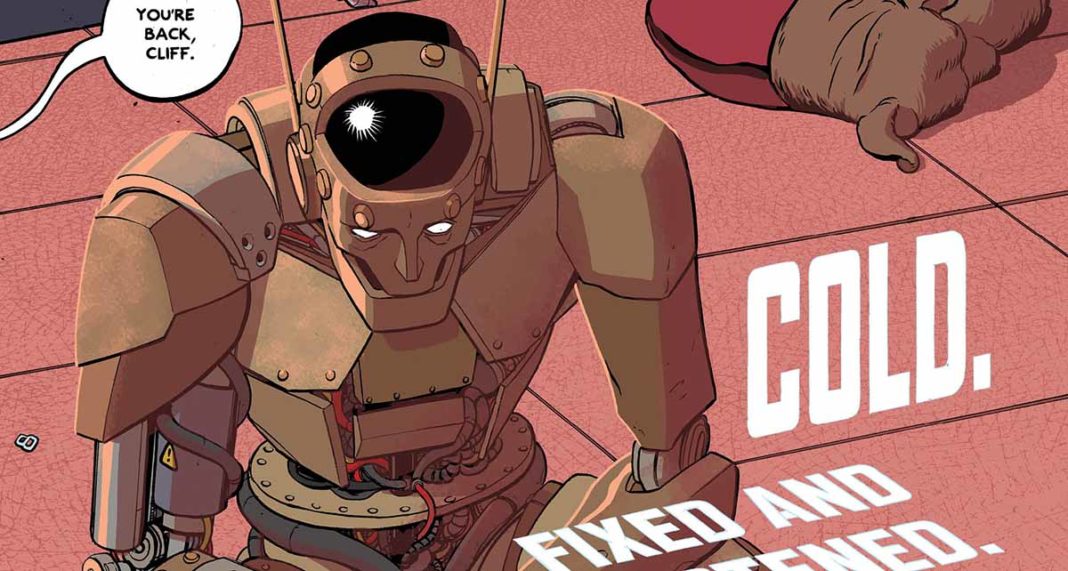

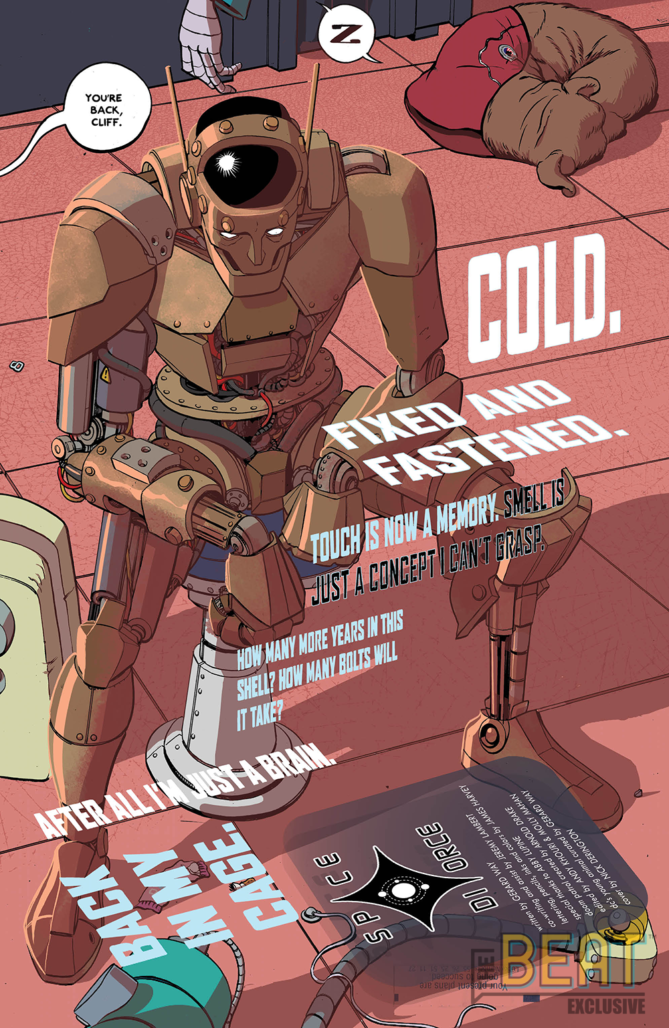

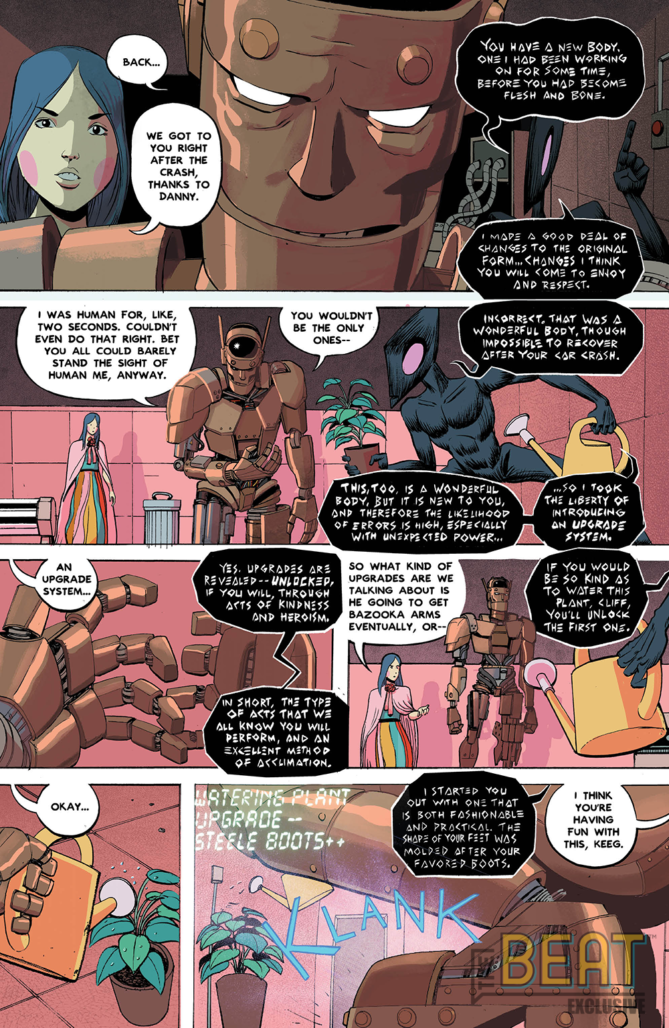

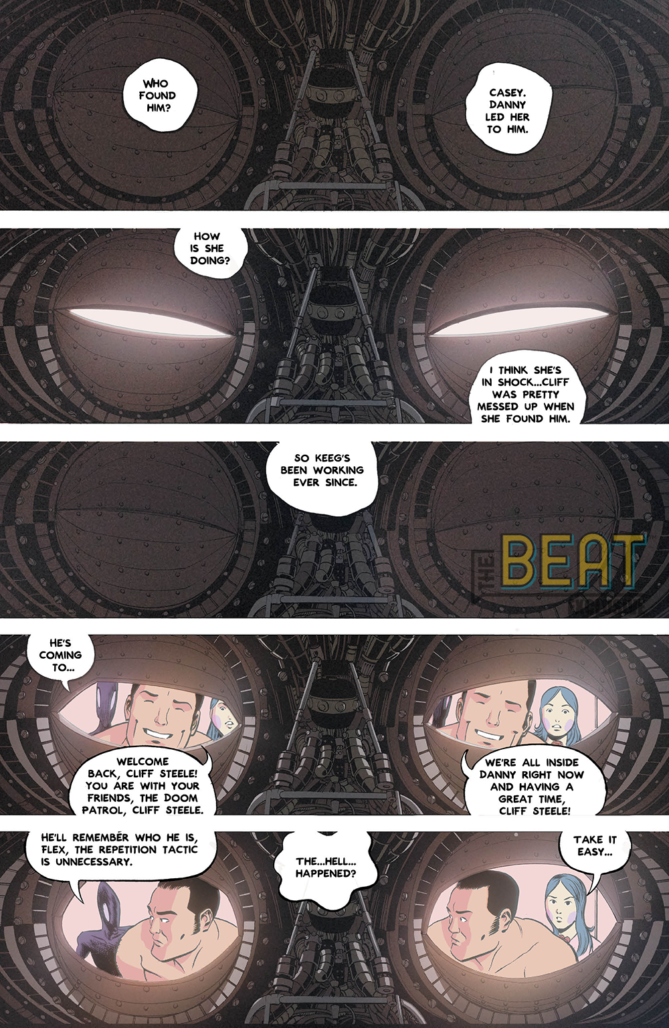

This isn’t a knock against Doom Patrol: Weight of the Worlds #2. I quite love this issue, in fact. It’s absurd and beyond comprehension, fusing video game-styled antics involving Robotman with an intergalactic family court drama that can ultimately only be resolved by the sentient cat-person, Lotion, digesting a positive energy baby that the Negative Man, Larry Trainor, has given birth to and thus gaining the ability to help others find their own personal tranquility. It reads as ridiculously as it sounds, but thanks to Way’s and Lambert’s indulgent writing style and Harvey’s dreamy artwork, the entire thing gels into a mass that leaves you with a smile on your face and ideas percolating in your brain– even if the ideas don’t actually amount to something particularly specific.

This is, however, a thought that came into my mind when I was considering the ways in which we tell stories more broadly in superhero comics. In the floppy format, creators press against many limitations: a set page count and regular deadlines are the most impactful of these. The deadlines (assuming you’re meeting them) limit some ability to experiment and play. The goal is to get the story out the door and make sure that the editor is happy, the artist can draw it, and that it’s not going to run over the plans of any other storytellers in the company. It doesn’t sound that easy because it isn’t. To do something novel under such tight conditions with so many other cooks in the kitchen requires a hurricane of good will and charisma– little of either has to do with actual storytelling. To be under a banner like Young Animal is essentially to be insulated from such conditions, but even then, you run into the page count dilemma.

Don’t misunderstand me — you can do a lot in 24 pages or less. Comics like Doom Patrol prove this with every issue. But in storytelling, every decision has a cost. Every panel you place in your story for a particular purpose takes away from your ability to fulfill another purpose. These costs are relatively manageable if your story is centered in the real world with mostly or entirely realistic conceits. Working under those conditions, you have the advantage of your audience coming to your world with a prior understanding of its rules; no messy narration or long backstories are necessary.

It’s harder in superhero comics because the concepts are so big — the history is so long. Every page you use to hold a moment to evoke emotional effect is a page you’ve lost the ability to explain the rules of your characters’ abilities or the culture of the fantastical environment you’ve thrown them in. Showing people things in the world becomes more difficult and you’re forced to tell them certain things instead — breaking a cardinal rule of writing and further grinding the elegance of the story down. Your audience presupposes some amount of visual action every month, but action only impacts if the emotional stakes behind those one on one fights and battles for the universe are properly built. Without earning the ability to effect, all you’re left with is an essay rather than a story. It can be the most beautiful essay in the world, but it’s like eating an airy dessert as opposed to eating something dense. Both taste good, but only one leaves you with that proper full feeling.

And sometimes you don’t want to feel full, for sure. Sometimes you don’t need to spend three hours watching a sentient ambulance go through existential angst in order to enjoy watching him take his friends on a journey to fantastic lands with fantastic problems. Sometimes reading an essay on Medium is what you need to get through the day when you can’t crack open a 300-page tome.

But man, it’s a little bit of a bummer that you can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Miss any of our earlier reviews? Check out our full archive!