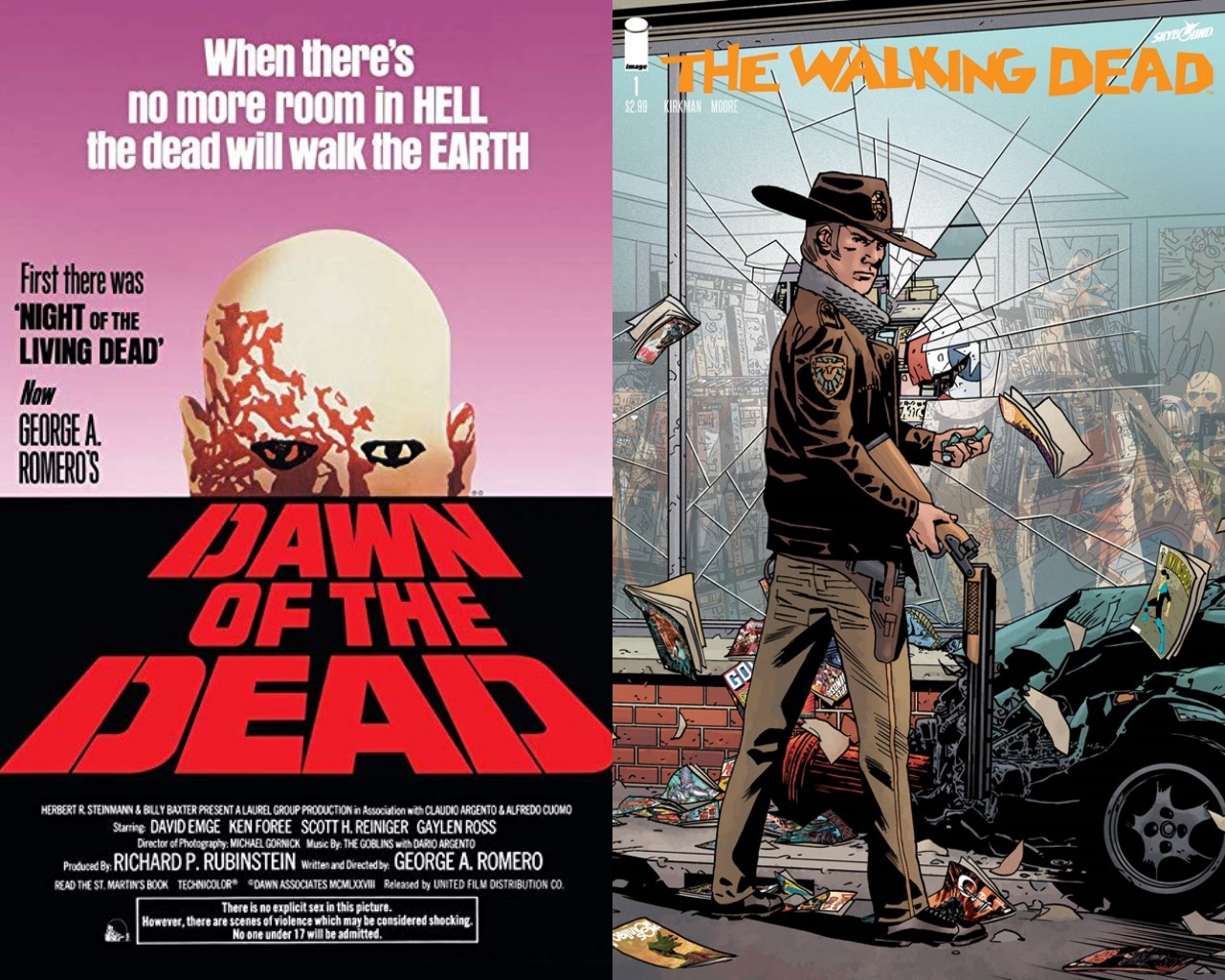

There’s Blood on My Comics! is a bi-weekly horror column about how our comics make us afraid of turning to the other page. But it doesn’t stop there! Oh no, it doesn’t. Each horror comic will be paired with a horror movie that shares a similar approach in getting those blood-curling screams out of us. It’s like pairing fine wines with perfectly cooked meals, or Blood Cocktails with sacrificial goat cheeses. This week: George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead and Robert Kirkman’s & Charlie Adlard’s The Walking Dead, part I.

A 20th Century Monster in a 21st Century World

When George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead came out in 1978 zombies had already become metaphors for purely social American nightmares, mostly thanks to the success of Night of Living Dead, the first movie of the Dead Trilogy. Night came out in 1968, during the most violent year of the Vietnam War and in a time when the counterculture was at its most active.

These zombies were seen as horror stand-ins for racism, unhinged militarism, and moral corruption. Dawn of the Dead gave the zombie an additional metaphor to hang on its sleeve: consumerism. Taking place in a deserted mall, zombies were seen roaming the halls and the still fully stocked stores as if by muscle memory. Even in death, shopping is still America’s favorite pastime.

By the time The Walking Dead arrived in 2003, the Romero zombie, while still considered the standard, was competing with the ‘gore for gore’s sake’ zombie that shambled in from the 80’s and into the 90’s straight from Italy’s horror cinema. These zombies, made popular horror directors such as Lucio Fulci, Andrea Bianchi, and Bruno Mattei, were walking bags blood ready to explode at a moment’s notice. Their gruesome factor was dialed way up at the expense of metaphor. These are the gory zombies that became mainstream outside the Romero trilogy (with notable exceptions such as Shaun of the Dead).

This isn’t a bad thing, necessarily. For a blood-drenched good time, look no further than the Italian zombie movies. They’re filled with the kind of ambiance and b-movie gore fans grew to love and expect to see in their zombie movies. Just don’t expect anything deep behind the rot. Although, Italian horror did give us a zombie vs. shark scene, which no one has ever complained about (and I’m not about to become a dissenting voice on this one.)

The Italian zombie, it can be barely argued, can stand as something resembling a metaphor so long as it’s about violence and the many forms it can take so long as they’re all extreme, but they’re a world apart from Romero’s zombies. They may not be politically charged, but they do produce a mighty image with the amount of gore the carry in any given scene. I would argue that the majority of zombies we get in comics owe a lot to the Italian zombie, which strips what little humanity Romero’s zombies have left and turns them into full monsters.

Robert Kirkman’s and Charlie Adlard’s zombies for The Walking Dead carry elements from both types, but they feel more naturally suited to represent the social anxieties and problems of the 21st century, much like Romero’s did for counterculture America. In this sense, it’s tempting to say they owe more to Romero than to Italian zombie horror. But The Walking Dead zombie might be in a class all of its own.

The question, though, falls on whether The Walking Dead zombie belongs to the same strain of zombie as Romero’s or if it’s become its own different version, deserving of its own category.

(Note: I will be focusing on Charlie Adlard’s zombie in this article. Tony Moore’s zombie is a part of the Walking Dead history, but it was Adlard’s that defined the series as he took over for the remainder of the series after the first volume.)

We’re the Walking Dead? No, YOU are the Walking Dead!

Kirkman & Adlard and Romero share the idea that the real living dead in their stories are those who refuse to accept humanity has died off. Rick, Kirkman & Adlard’s main character, says as much in the often quoted Walkind Dead #24, where he tells the group “We are the walking dead!,” letting everyone know that the living are still the problem in their dead world. Romero does it through the now iconic scene where Dawn’s main characters ask themselves why the dead are flocking to the mall. Peter, played by Ken Foree, gives his classic explanation here:

Francine: They’re still here.

Stephen: They’re after us. They know we’re still in here.

Peter: They’re after the place. They don’t know why, they just remember. Remember that they want to be in here.

Francine: What the hell are they?

Peter: They’re us, that’s all, when there’s no more room in hell […] Something my granddad used to tell us. You know Macumba? Voodoo. My granddad was a priest in Trinidad. He used to tell us, ‘When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.’

I want to get this out of the way first as both TWD and Dawn lean heavily on the living being the actual “zombies” in their worlds. There’s a lot to be said here, but my focus here is on the literal living dead, on that which has died and come back hungry for human flesh. It’s important, though, to recognize that the living’s moral complexities allow the real zombies to become the metaphors they eventually embody.

For TWD it’s about how humanity has become this mindless homogeneous mass synchronized in thought, prejudice, and behavior that makes them easy to lead. In Dawn it’s all about how society creates its own zombies by numbing people with consumerism to keep them ignorant and infinitely controllable.

In both cases, the zombie is an extension of the living, a continuation of life once humanity surrenders free will in favor of flock mentality. This makes the zombie a much stronger metaphor for the problems each story addresses. The Walking Dead looks at the inherent frailty of small communities and how they easily they can be corrupted by playing with the idea that survival should be a selfish endeavor rather than a collective project.

Here’s where the Kirkman & Adlard’s zombie meets and challenges the Romero zombie, from a metaphorical standpoint all the way to how it all influences their visual design.

To be continued in part II.