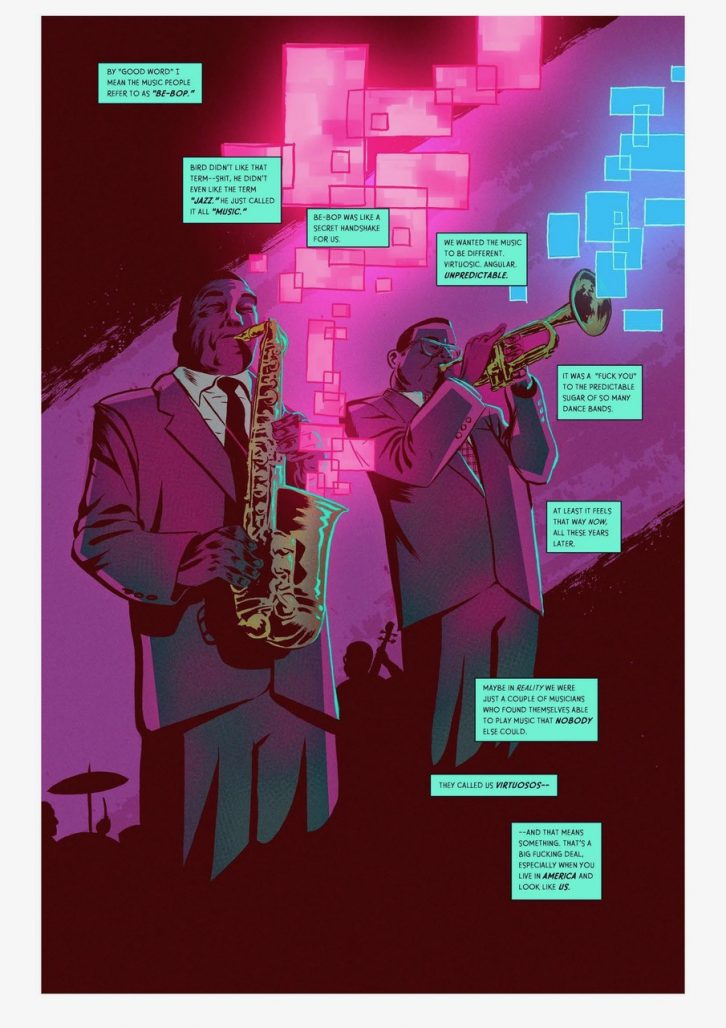

As art forms, both jazz and comics are extremely expressive and deeply personal. To be an artist (or admirer) of either medium takes discipline and a sense of history. No one can wake up one day with an entire vocabulary of either art form. That is why fans of each are deeply protective of the respective traditions that both jazz and comic engender. On the other hand, the rules are always made to be broken. And when they are, the results can be mesmerizing.

Charlie Parker was one of the twentieth century’s most innovative musicians. Voracious in virtuosity as he was in vice, Parker’s legacy over jazz is still felt to this day. For Parker, constant innovation was the name of the game. While there have been many books written about Parker, also known by his nickname ‘Bird,’ there has never been a comic biography of the jazz legend. Until now.

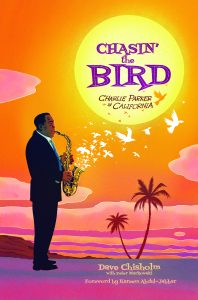

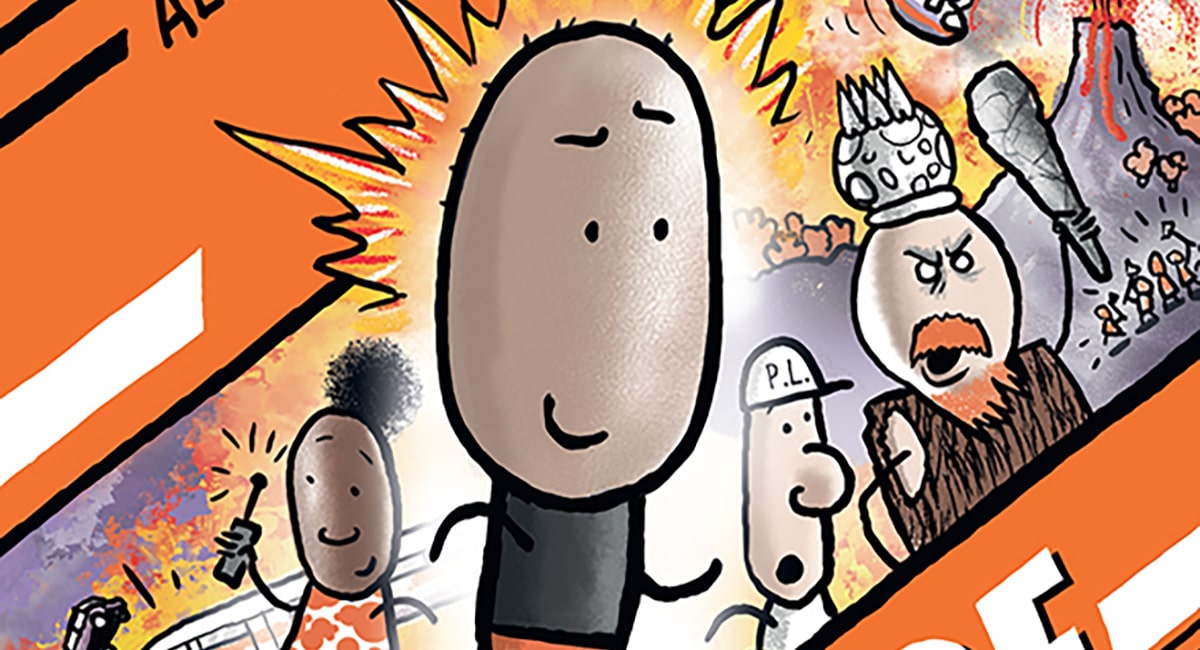

Next month, Z2 Comics will release Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California, a phantasmagorical graphic novel written by Dave Chisholm. Told in six parts from the perspective of Parker’s associates, Chisholm weaves a tale of Parker as a constant wanderer, a frustrating friend, and, simply, a genius. With a bright color palette to match a Los Angeles skyscape, this sun-soaked book is one of the most stunning pieces of visual media to come out in 2020.

I recently sat down with Chisholm, who besides being a cartoonist is also a trumpet player, composer, and educator currently residing in Rochester, NY, to talk about the book, what Parker means now in contemporary America, and how to understand the art of someone who we maybe shouldn’t seek to emulate on a personal level.

AJ FROST: Hi Dave! So nice to chat with you today. Before we started our interview, I listened to a recording of “Donna Lee” to get me into the mind space of the late, great Charlie Parker. Before we talk about your new book, I wanted to ask what Parker’s work means to you. And what does it mean for American music in general?

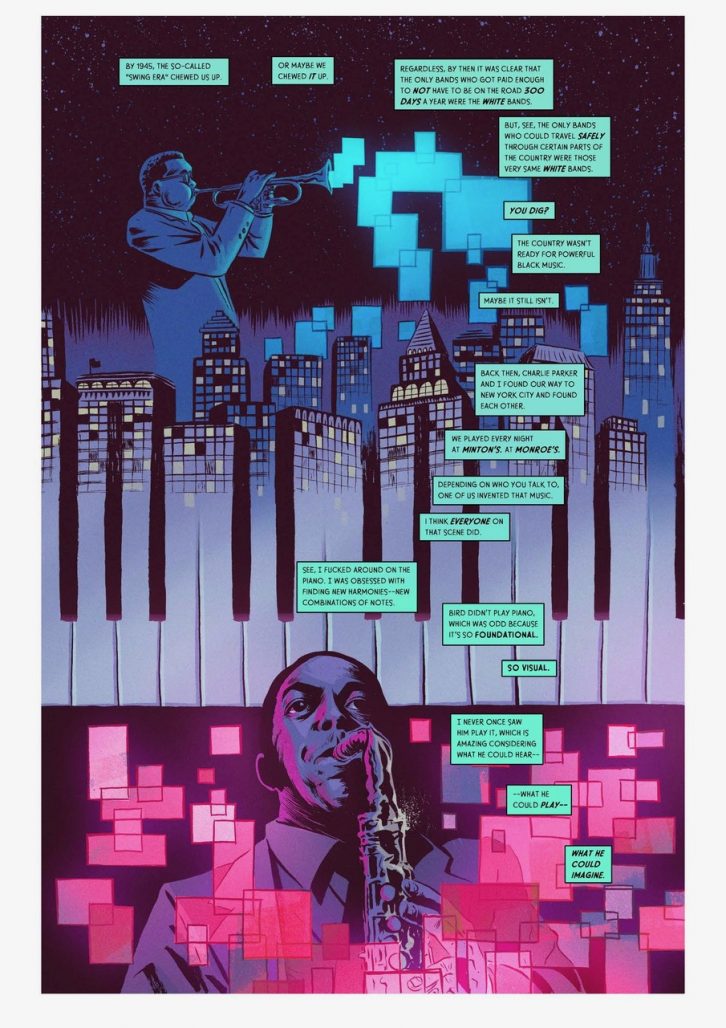

DAVE CHISHOLM: I’ve spent the majority of my life studying this music—this Black American Music that we call “jazz.” Ten years in college, three degrees, and tens of thousands of hours learning and playing this music, and so much of this music stems from Charlie Parker. When we consider Parker’s position in the greater fabric of American music, he’s such an integral fountainhead for the transition of the public’s awareness of this particular type of music from commerce to art. Parker’s music was simultaneously aggressively avant-garde for his time AND also fully integrated into the lineage of the folks who came before him. It’s staggering!

FROST: What do you think was most avant-garde about Parker? What did he bring to jazz that no else did at the time? Or, perhaps, since?

CHISHOLM: I think it was a combination of a bunch of traits of other players before him: the rhythmic freedom and sophistication of Lester Young–unpredictable, free-flowing, odd phrasing that goes over the barline, obfuscating the form of a song, plus the harmonic sophistication of Art Tatum, a total mastery of the blues language, and a true virtuosity on his instrument. Nobody had combined these elements before him and he frankly elevated just about all of them on top of his combination. Lightyears ahead!

You ask “since” and really it’s hard to say because his vocabulary became synonymous with jazz improvisation even really within his brief lifetime so now when you hear any jazz–whether it’s from top-tier players or a cocktail-hour wedding group–you will likely hear some sort of distillation of Parker’s musical vocabulary. It doesn’t sound avant-garde any more unless you try to listen with that historical knowledge.

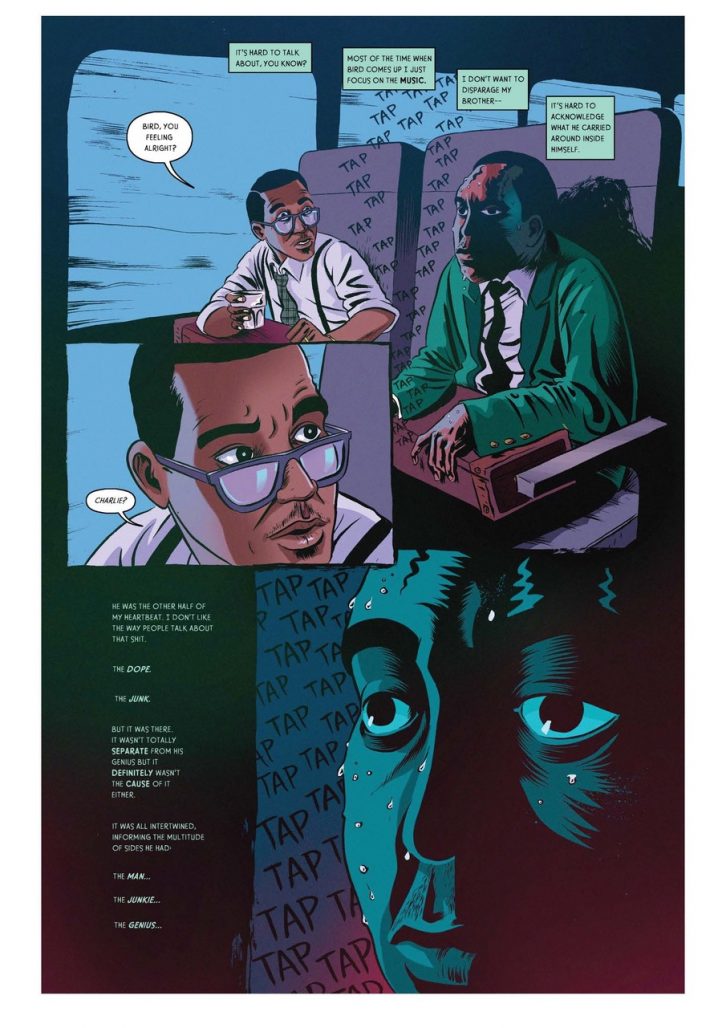

FROST: That leads to my next question. When we listen to or read about Parker’s story today, there are so many elements to it: There’s the excessive drug use, the debauchery, the vices of a man who used his genius to hurt others. Yet, he was still a genius in every possible way. How do we reconcile the history of the man with the history of his contribution to music?

CHISHOLM: I think when you look at a person like Parker, with all of these troubling details, I think it’s still important to recognize the humanity in him and to examine the various WHYs behind these behaviors. I think with most of us, the very traits that make us great at whatever we do can also reveal the seeds of our own self-destruction given the wrong circumstances. With Parker, this obsessive streak that’s obviously present could be interpreted as the root of both his excellence as well as his excesses. When you combine this with the fact that he was a Black man living in America during a time when that alone could be a death sentence—and really has that changed?—it all becomes a recipe for a person whose penchant for excess became a constant pursuit of escape from the troubles of life. This understanding helps build compassion, empathy for the man, and also frames his music in a new light.

FROST: So, moving onto your new book Chasin’ the Bird, what prompted/inspired you to pursue this project?

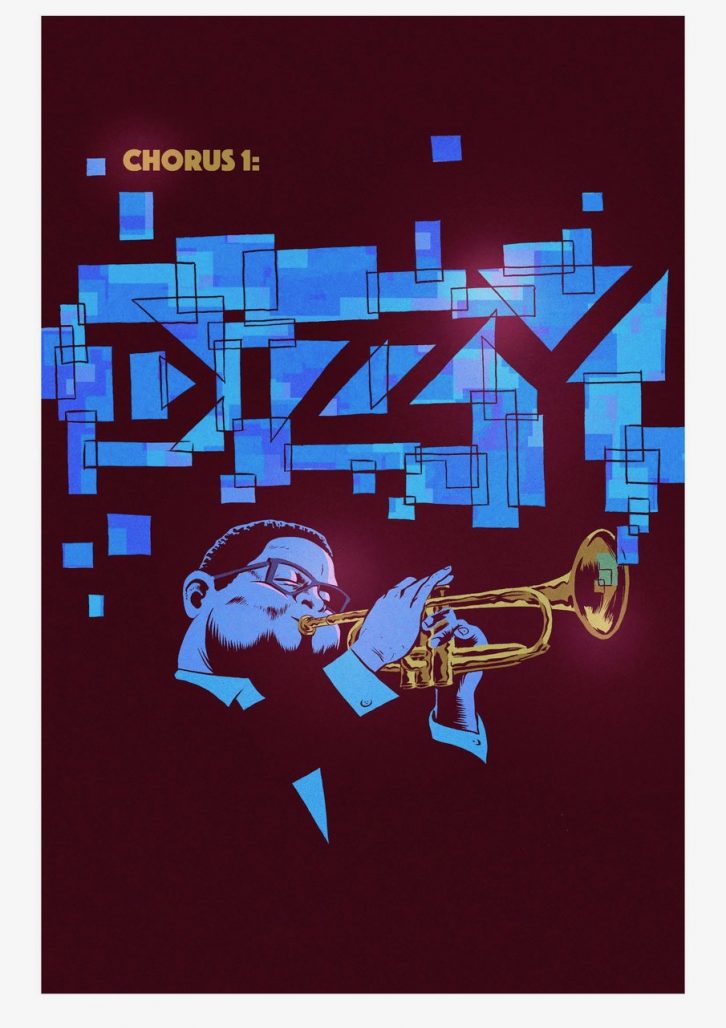

FROST: What I found fascinating about the book is that it’s not a linear re-telling of Parker’s life or even a period of his life. It’s a kaleidoscope of perspectives. Can you tell me about how you came to structure the book into these vignettes of Parker through the eyes of others, including Dizzy Gillespie?

CHISHOLM: Knowing Parker’s legacy—and so much of his legacy is in this grey area between truth and myth—so much of it is irreversibly altered by the points-of-view of the folks who knew him and who admired him, loved him, hated him, or whatever. I wanted this story to speak to that grey area. For all accounts, Parker was a difficult person to really know. He was playful, he was moody, he was artistic, he was chaotic, charismatic, mysterious, brilliant—and I immediately knew this was the best way to explore this subject. At that point, research became a quest for different people whose lives intersected with Parker’s during this span of time, looking for entertaining, unique stories that could become vehicles for exploring Parker as well as the various themes that needed to be explored in such a project.

FROST: In a word, the book’s art is simply gorgeous. I have a process question and then an aesthetic question. On the process side, how did you go about recreating 1940s Los Angeles? On the aesthetic side, what guided you in terms of the visual layouts?

CHISHOLM: To answer your first question, I used as much visual reference as I could find to try to create as much authenticity as possible. I’m sure there are still mistakes!

The layouts/storytelling was guided by, well, first and foremost I want my storytelling to be clear and effective. There are lots of ways to tell a story clearly, though, and so beyond that, the storytelling of each chapter was intended to reflect the unique point-of-view of each narrator. How would Dizzy Gillespie’s POV look in a comic vs. William Claxton, vs. Julie MacDonald, vs. Coltrane, vs. Ross Russell? Each person has a unique POV and it allowed me to generate different storytelling “rules” for each chapter

FROST: May I ask why Miles Davis wasn’t more of a presence in this book? He certainly played a part in Parker’s life.

CHISHOLM: Even though Miles is only a little bit younger than Parker, his role in Parker’s life really seemed as an apprentice while Parker was the master. I know this is an oversimplification. However, Davis’ first major historic moment was arguably the Birth of the Cool which served as almost a reaction against the pyrotechnics of bebop. Of Parker. It didn’t seem like a leg of the story that belonged here, it felt like it would pull focus away from Bird. Davis does make an appearance briefly in the Claxton chapter, though. Given the space constraints of the graphic novel format, it didn’t make sense to have him as a major player.

FROST: Can you talk about Peter Markowski‘s coloring in the first chapters of the book? It’s stunning, bright, and varied from chapter to chapter. How do you think he contrasted from your coloring choices?

CHISHOLM: Pete’s my oldest friend. We used to hang out as kids and draw comics, invent universes; it was a dream for both of us. He’s now this amazing figure: an art director for DreamWorks Animation! When we were looking for a colorist, I approached Pete because I really wanted to work with someone who I could really talk to at great length about it. His work turned out so beautiful. Once COVID-19 hit, his work ramped up in the animation industry and so that’s why I ended up coloring chapters 5-6 and the outro. But yeah, his palettes for this are so great and really make those chapters pop!

FROST: Comics are such a visual medium, but with Parker, you have many segues into the spiritual side of music. I’ve also seen this in other books about musicians, including the biography of Glenn Gould. How did you convey the auditory philosophies of Charlie Parker on a silent page?

CHISHOLM: This is another instance in which the vignette approach proved fruitful as it allowed me to portray music in a variety of different ways, from the “jazz squares” in the Dizzy chapter to the flowing music notation in the Zorthian chapter to the slightly didactic bits in the Claxton chapter all the way to the finale with the extended “musical” sequence. It’s a huge challenge that is frankly always doomed to fail in the sense of creating a 1:1 synch with the audio experience but in those failures, you can innovate some very fresh page designs that undeniably FEEL musical.

FROST: What was the biggest challenge for you during the creation of this book? And what are you most proud of now that it’s about to be released?

CHISHOLM: First off, the whole thing was an absolute dream to create from beginning to end. I’ve never created a work that came together so quickly, so easily, and so well. That said, I’d say the biggest challenge was maybe this understanding that, in telling Parker’s story, there are topics that needed to be in there: understandably sensitive topics like race, addiction, sexual mores, and less-sensitive topics like accurately and concisely defining Parker’s contribution to music and his role in music history, both in terms of what came before him and what came after him. The challenge was speaking to these topics with sensitivity and as much authenticity and nuance as I could bring to the table in this graphic novel form.

To be honest, AJ, getting this opportunity to tell this story is the biggest professional honor of my life and I do think the book turned out great. I’m so proud of it, every aspect. The estate and Z2 were encouraging of me to take risks, to not make a safe, boring book, and I ran with it and I’m so stoked about it.

FROST: How did Kareem Abdul-Jabbar come to write the introduction?

CHISHOLM: I’m honestly not sure how Kareem ended up doing the Foreword but either way I’m so so grateful for his powerful words.

FROST: How does this book speak to the current moment of the empowerment of Black people through culture and music?

CHISHOLM: That’s a hard question. I completed work on the book in March 2020, before the current (and necessary) wave of BLM activism. I don’t think that’s a question for me to answer, to be honest. It would be presumptuous I think. I did my very best to do the work, do the research, and tell the story in a way that speaks to the atrocities and hardships that Black Americans have faced without being exploitative. Whether or not it speaks to the current moment is not up to me.

FROST: Just one more question: There will be those readers like me who are familiar with Parker’s music, and there are people who won’t know a single thing about the man. What do you want readers to walk away with knowing about Charlie Parker the innovator, Charlie Parker the flawed genius, and Charlie Parker the man?

CHISHOLM: I want readers to have a greater understanding of his place in history and also an image of the man as a human being, warts and all.

I mean, really I have two BIG goals for this book that are each sides of the same coin:

1) I want comics readers to listen to Parker’s music and to explore the immense world of jazz music. There’s so much simpatico between these two worlds, it’s just meant to be.

2) I want jazz heads to have their minds blown about the capabilities of the comics medium. You can tell ANY story in this medium. It’s a perfect storytelling medium.

I want more people to listen to this incredible music and more people to read incredible comics! Is that too much to ask?!

FROST: Thank you so much for chatting, Dave!

CHISHOLM: Hell yeah, AJ. I’m glad you enjoyed the book!

Chasin’ The Bird: Charlie Parker in California will be available in October from Z2 Comics. Learn more about Parker here. Read more about Dave Chisholm’s comics work and music on his website.