The horror genre has been catering to a vast community of people in different forms: films, TV shows, books and comics. We’ve been pushed to think beyond the jump scares, special effects and hoopla, to question specific intentions behind fictional characters who hint at queerness or “otherness” in horror stories. Queer Horror, a panel put together by Comic Con International and Prism Comics for Comic-Con@Home 2021, explored this genre with host Michael Varrati (The Boulet Brothers Dragula, Unusual Attachment) and panelists Drusilla Adeline (Dead for Filth, Sister Hyde Design), Darcie Little Badger (Elatsoe, Strangelands), Terry Blas (Reptil, Dead Weight), Trinidad Escobar (Crushed, Bruhas), Joamette Gil (Power and Magic: The Queer Witch Comics Anthology), and Steenz (Archival Quality, Heart of the City).

Gil’s obsession with horror began quite early on in their life, reading the Goosebumps series and watching thriller films. Having their Cuban grandmother babysit her and allowing her to watch Child’s Play (1988) while having “no idea that a 5-year-old” left an everlasting impact on her. “I didn’t get into horror,” Gil confessed. “Horror got into me. It was the antidote to gaslighting. If you were having a negative emotion, your parents didn’t understand you or validate your feelings, the dark side was an acknowledgment that you’re not crazy; bad things are real.”

Most of us either like a genre because it gives us an escape from reality or represents us in ways that helps us understand ourselves. The later plays a major role in the queer community. Varrati describes this genre as a medium for controlled catharsis where we can’t control the fear of the world yet feel a “controlled element” with movies and books that allow us to release our fear into. He quoted Wes Craven: “Horror films don’t create fear. They release it.”

The otherness depicted in these films is most likely to be understood by the queer. Gil explains this relatability factors in because the way fear is induced in scripts. “As a queer person, I can find a validation in horror, like having desires that are considered otherworldly,” they said. “We are basically told we are not natural. In movies, people with disabilities and facial deformities are the easiest tropes.”

Adeline shared similar thoughts with Gil. For her it’s beyond a trope, that transgender people are either depicted as killers or suffering from a mental disability. “There’s an entire sub-genre of body-horror from almost a trans-lens but made from cisgender filmmakers who don’t know what they are doing presents a gender euphoria and trans characters in a positive light,” she said.

One of the happiest on-screen moments for Adeline was watching Martine Beswick‘s transformation in Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971). Most trans characters are either vilified, attacked or killed so scenes like these connects the community even more. “We want them to have a happy life so much and we have only accidentally gotten beautiful complex characters,” she added.

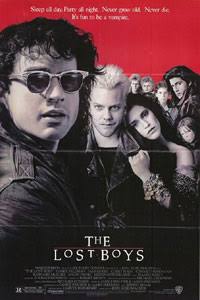

Representation comes in many forms, be it big or small. Ever notice a ‘strange’ cat person in a horror movie being killed off within the first few minutes? Or that ‘gothic’ teenager fuming with metaphysical angst who runs a single-person club about bringing justice to vampires? These subtle references go deeper than culture and history. Badger has always found a deep connection with vampires because of their intense desire for blood, something that we all have. “It can be played in a lot of ways and it doesn’t have to be sexual,” they shared.

Varrati reinforced that vampires are queer, at least the modern ones and all these tropes go back to Sapphic literature of the gothic era, which is further proof that queer folk have been influencing the horror genre since the very beginning.

Here are some read-and-watch suggestions from this panel:

Drusilla Adeline:

Darcie Little Badger:

Terry Blas:

Steenz:

Joamette Gil:

Miss any of The Beat’s earlier ComicCon@Home coverage? Find it all here!

I appreciate this write up! Just one note: transgender is an adjective, so “transgenders” is incorrect (and usually considered offensive). “Transgender people” or “transgender characters” would fit better. Thanks!

Thank you! I’ve updated the post.

Comments are closed.