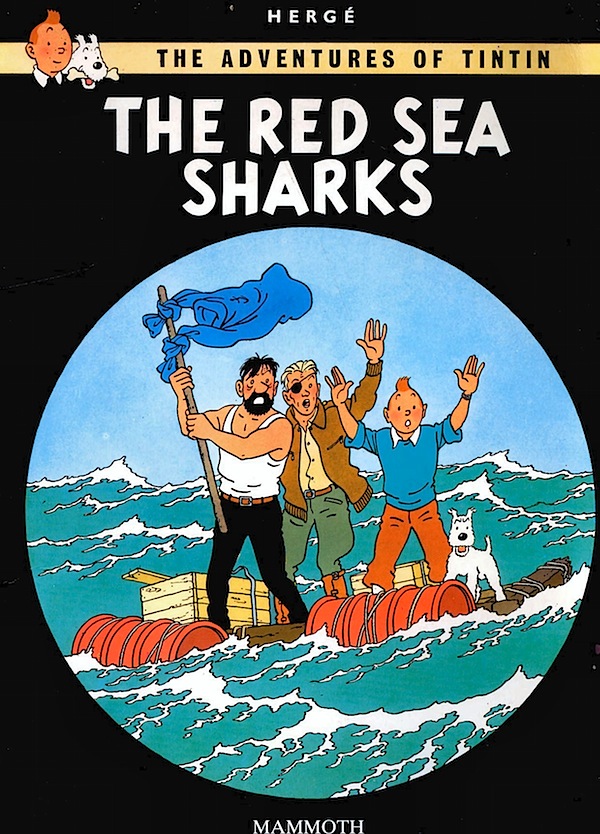

In a shocking court reveal over the fate of one of the world’s most beloved and influential comics characters, a Dutch court has ruled that Moulinsart, the company that runs the publishing and licensing business of Tintin, does not own all the rights.

The stunning result came about during a court case in which Moulinsart sued a Dutch Tintin fanclub over using images of George “Hergé” Remi’s beloved boy reporter. Moulinsart is known for pursuing any and all outside uses of the character, even benign ones such as fanzines.

During the case, a legal document from 1942 was produced showing that Hergé had assigned the rights to the character to his publisher, Casterman.

The Hergé estate is currently run by the man who married Hergé’s widow, and he’s quite unpopular with fans and industry watchers, for running the estate with an iron fist, including such things as suing fanclubs over use. That this stunning document showed up in just such a case is a twist that you’d find incredulous in a film. But it really happened.

It’s kind of hard to give context to this, but it’s like, let’s say sometime in the future Prince George is about to ascend to the throne of England, and someone suddenly produces a paper saying Queen Elizabeth was actually from New Jersey and was never queen.

“It appears from a 1942 document… that Herge gave publishing rights for the books of the adventures of Tintin to publisher Casterman so Moulinsart is not the one to decide who can use material from the books,” said the Hague court’s ruling, seen by AFP on Monday.

The document came from a Herge expert who wishes to remain anonymous and its validity has not been contested by Moulinsart or the author’s family.

“The big question is to know whether they (other fanclubs) have to continue paying Moulinsart,” said Herge Society secretary Stijn Verbeek.

So yeah, some Tintin fan was sitting there going “Suffering succotash!” while sitting on an explosive document that would affect the ownership of the character considered the most influential in the history of Franco-Belgian comics. And to think that perhaps people at Casterman or even the Hergé family themselves knew of it…and kept this secret for years. Like I said, it’s an amazing storyline.

Tom Spurgeon has a lot more background on this including comments from euro-comics expert Bart Beaty:

“Reaction in my social media has been a mixture of pure shock — my own first reaction — and a good deal of joy. It is important to bear in mind that Nick Rodwell, who runs Moulinsart, is one of the most disliked people in European comics amongst fans. The husband of Hergé’s second wife, he has taken hold of the Tintin empire and consistently reined over it in a way that antagonizes fans and scholars (Moulinsart is relentless in the protection of the Tintin copyrights even to the point of discouraging academic study of the Tintin books). More than a few people feel that Casterman would be better stewards of the Hergé legacy than the man who married his widow.

Here’s some more from a 2010 newspaper piece that documents growing unease with Rodwell’s running of the estate:

Hergé himself had given little thought to the business of merchandising. “He was involved only in his creation, in his works,” Vlamynck told a French television interviewer last year. He had all but forgone any oversight of Tintin merchandising as part of a deal to restore his reputation in 1945. Hergé had produced comic strips for Le Soir newspaper throughout the war, even after it came under the control of the occupying Germans. His perceived collaboration barred him from newspaper work at the end of the war. Raymond Leblanc, a prominent Belgian resistance figure, offered him a solution: Leblanc lent Hergé some of his anti-Nazi credentials by going into partnership with him; in exchange, Hergé licensed his hero’s image for use as a marketing tool. Forever conscious of the favour, he never broke off the deal; the Tintin-branded mustard pots and more were the result.

Under Rodwell, this began to change. Moulinsart terminated all but a few of its long-running licensing contracts. It was not that the group wanted to curb Tintin’s appearances totally but Rodwell hoped to control the brand more effectively and apply more consistent standards by developing products in-house. What emerged over time was a centralised merchandising policy that pushed the brand relentlessly upmarket. The number of retailers authorised to sell the goods was reduced, creating a scarcity that had not existed before. It reflected the new ambitions: Rodwell began speaking of Tintin as the “Rolls-Royce” of comics, unworthy of being associated with cheap trinkets and give-aways.

Lots more background in that link.

This stunning result will doubtless have major implications for the Tintin books going forward—a publishing series that has already been published in more than 70 languages and sold more than 200 million copies. Back royalties? Refunded rights? Oh boy…developing.

“Suffering succotash!”?

Surely “Blistering barnacles!”

There are few more Draconian organizations than Moulinsart (maybe the Conan Doyle estate) so I’m happy for Tintin to be in almost any other hands than theirs. Suing fan organizations for promoting your character is tacky at best.

This is another example of why I have problems with copyrights lasting longer than the creators of the works themselves: the legal heirs of the creator can be assholes who have no moral right to control their work. If Hergé was still alive and wanted to be a prick and sue fanzines, that would still make him a prick, but it’d be his baby so that’d be his right. But this Rodwell guy had absolutely nothing to do with creating Tintin, so why should he have control over it?

Really interesting, we’re doing a Tintin podcast and will be talking about this in a later episode… http://www.sneakydragon.com/category/podcast/totally-tintin/

In 1942 Belgium was under german occupation, and they were Known to take interest in anything being published, so there might have been some pressure there.. this might be a point in future trials, so this might not be over.

“you’d find incredulous in a film”

No. You would BE incredulous, you might find it incredible.

Comments are closed.