Latinxs have a tough challenge in the year ahead as the narrative surrounding the community’s place in comics takes shape. Comics have become more inclusive both inside the comics page and outside of it, with creators commenting on their identities and their heritage as a source of raw material for their stories.

In an interview for SYFY.com, Vita Ayala, one of the industry’s rising Latinx stars, spoke about Wonder Woman being Puerto Rican because she looked like one of their cousins, with the short shorts and the tiara and the golden bangles. As a Latino myself, stories like these made me think of other creators who shared a similar experience but weren’t really asked to talk about them specifically, most notably in past decades. Maybe we should start digging for stories like Ayala’s to get at, hopefully, a stronger narrative of Latinxs in comics, one that gives us more mainstream visibility throughout the different time periods.

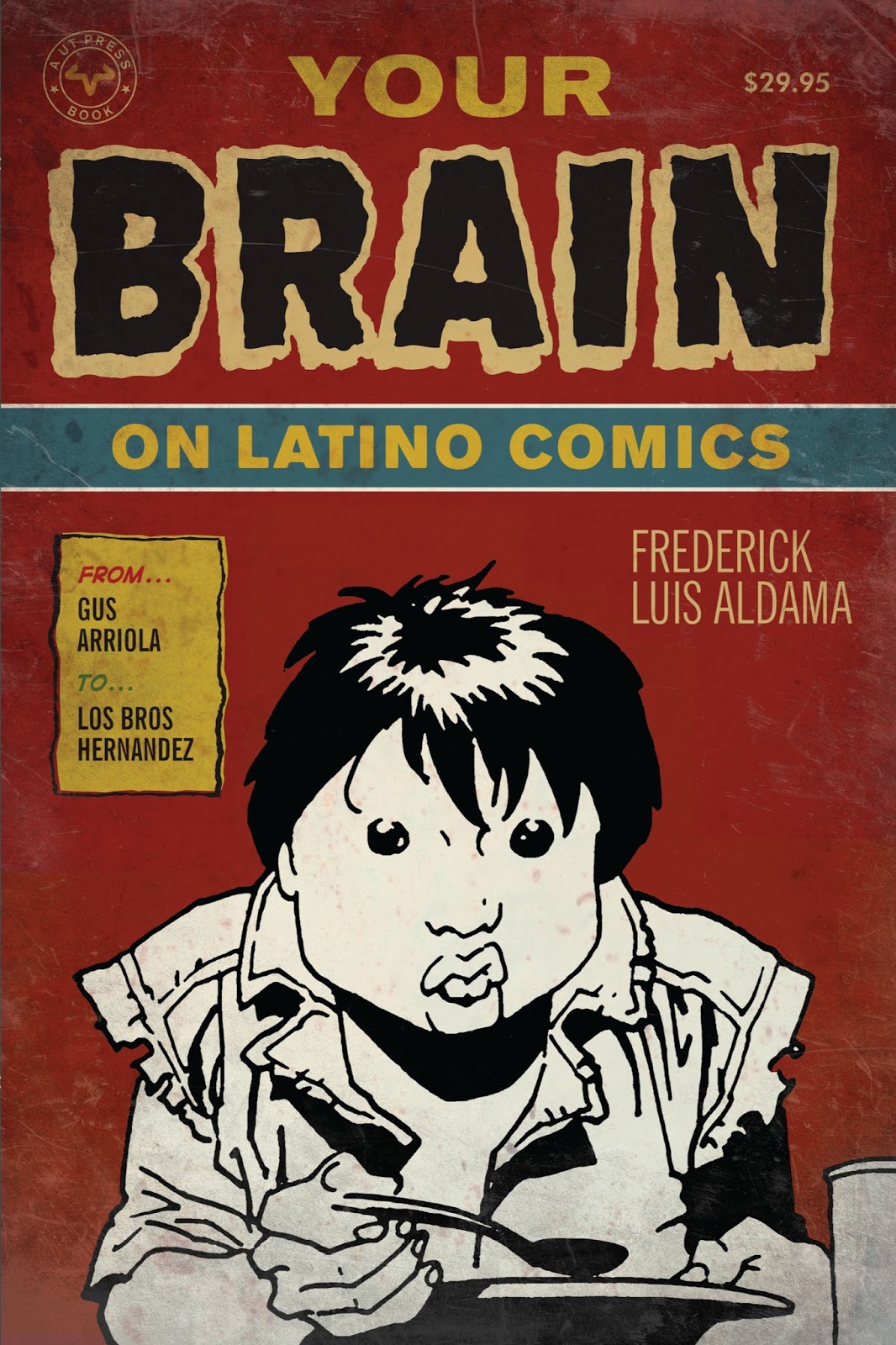

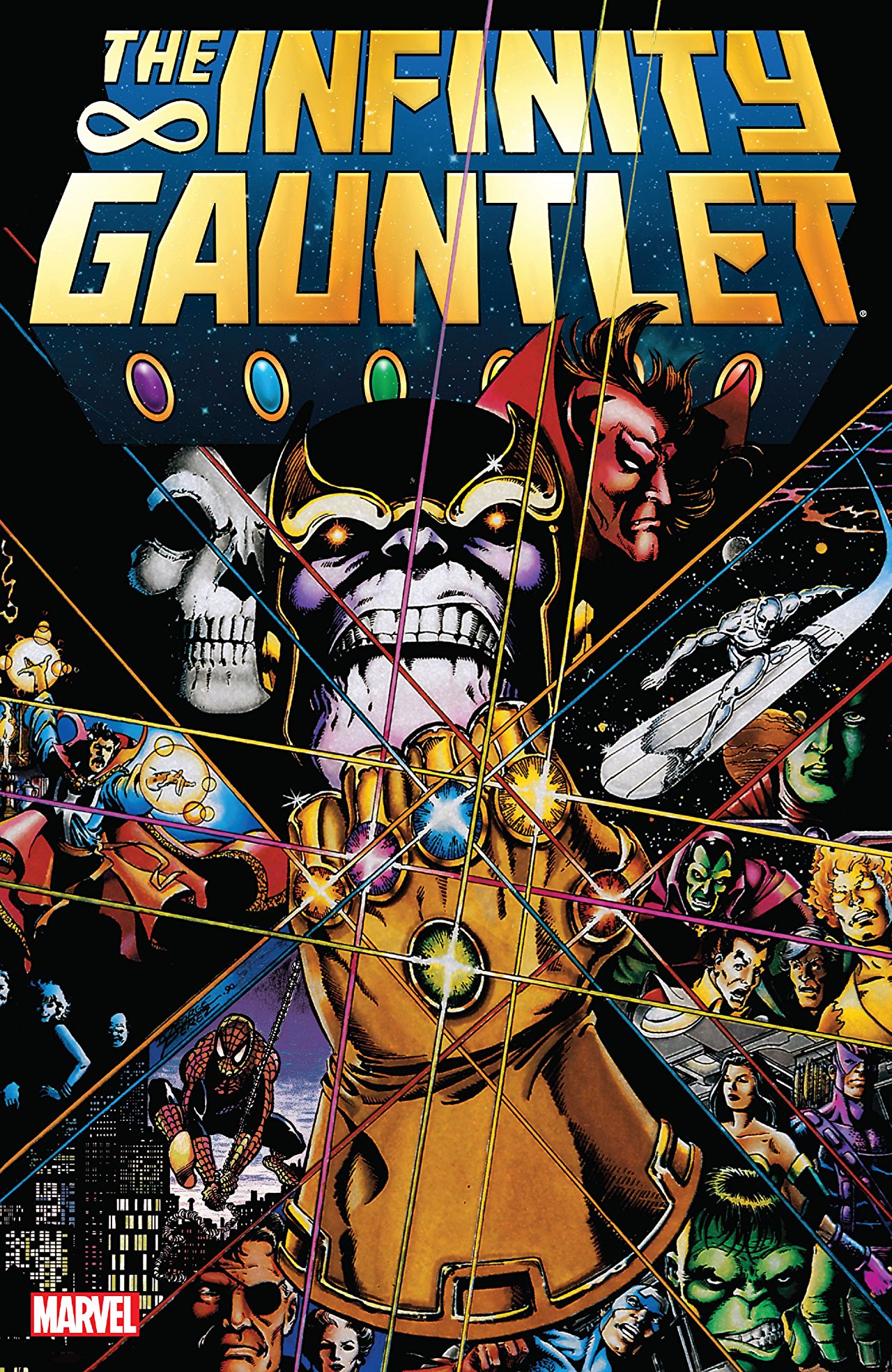

One of the problems this Latinxs in comics narrative faces is that the stories that comprise it are quite scattered. The legendary George Perez, for instance, has been a powerful figure in the comics world, with an extensive resumé that includes classic runs on The New Teen Titans, Wonder Woman, and Avengers in addition to being part of the creative teams behind some of the most important comic book events in the history of the medium, namely Crisis on Infinite Earths and Infinity Gauntlet. While I consider Perez’s work to be of titanic importance to the history of Latinxs in comics (and comics as whole for that matter), I’m not so sure how the larger comics community sees his place in it as a Latino comics creator specifically.

Fabián Nicieza, co-creator of Deadpool, is another creator that I consider important in this story. Nicieza was born in Argentina and has talked about how his identity adds flavor and color to the characters he created or helped create, Deadpool included. Does that mean that Deadpool figures into the history of Latinxs in comics? Is Nicieza seen in mainstream media as a Latino comics creator or is that detail reserved for those who dig a bit deeper into his profile?

These type of questions can lead to people having the idea Latinx creators are just now crashing into the comics scene, when that assumption is just incorrect. Spectacularly so.

Thankfully, there are several groups within the comics community trying to address this visibility issue. In 2017, Héctor González Rodríguez III, creator of the comic El Peso Hero, called together the first ever Texas Latino Comic Con. In an interview he gave to NBC News that same year, González Rodríguez stated that the convention’s objective was to make clear that representation matters. The convention featured among its guest creators Richard Domínguez (El Gato Negro), Sam de la Rosa (Spider-Man), and Héctor Cantú (Baldo).

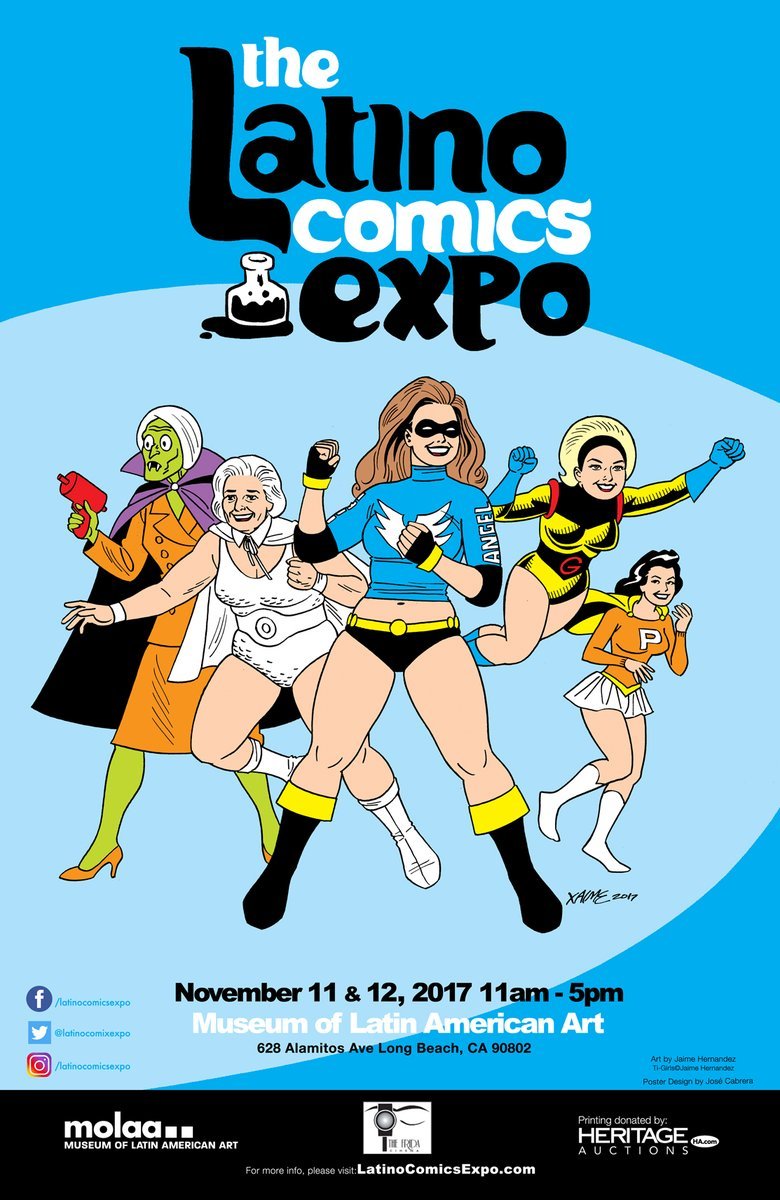

Another Latinx-focused comic con came in the form of Ricardo Padilla’s and Javier Hernández’s Latino Comics Expo, which was first held in 2011. This is considered the United States’ first ever Latinx comic con. It has been held in the Cartoon Museum of Art (San Francisco), the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library at San Jose State University and the Museum of Latin American Art, in Long Beach. Jaime Hernández, of Love and Rockets fame (a hugely acclaimed series of comics that look at representation politics and the social anxieties they create within the Latinx experience), has collaborated with the Expo’s organizers and has illustrated promotional art for the event. The next show is set for March 15-16, 2019.

These type of conventions do a great job of connecting Latinx creator stories into a more cohesive narrative, especially by putting the identities of their guest creators at the forefront of the convention experience. Latinx comic cons are putting the pieces of the puzzle together, making the story more accessible. It is in these spaces and the work exhibited in them that we can appreciate the complexity, the extension, and the scope of the Latinx community’s contribution to comics.

That Jaime Hernández has been a part of the Latinx Comics Expo, for instance, does a lot to bring forward our identities into the mainstream. And we need to do it with other creators that haven’t necessarily had the chance to let their Latinx identities accompany their public personas, be it by how comics media presents them or how publishers choose to promote them through their work.

Names like Edgardo Miranda-Rodríguez, creator of the Puerto Rican superheroine La Borinqueña, are starting to be mentioned in conversations surrounding the Latinx presence in comics. Miranda-Rodríguez’s character has already helped gather funds for grass-roots organizations looking to rebuild Puerto Rico after Hurricane María with the publication of Ricanstruction: Reminiscing & Rebuilding Puerto Rico.

Lions Forge also supported Puerto Rico’s hurricane recovery efforts with the release of Puerto Rico Strong, a comics anthology by Puerto Rican and Latinx creators that reflects on the problems that both preceded and came after María. Nicieza is featured in the anthology along with Ayala (Wonder Woman, Livewire, The Wilds). Ayala (who uses they/them pronouns) is an interesting creator in that they favor crafting stories and characters that navigate diverse identities in a very specific manner. Their characters aren’t governed by generic identities that can serve as heteronormative avatars for wider audiences. They struggle and question their identities, and they approach the question of what it means to possess these identities in a genuine way that is relatable to readers who share in them. And more Latinx voices are taking this same approach when crafting their tales.

These anthology books offer a vibrant and hopeful look at our future in the comics world. The creators featured in them aren’t just contributing stories, but contributing Latinx stories within new or often overlooked modes of thought, and even within classic comic book tropes, processed through the Latinx experience.

While we’ve definitely seen progress, our struggles with mainstream visibility are still alive, and kicking hard. And yet, creators like Ayala, Miranda, Natacha Bustos (Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur), Adriana Melo (Star Wars: Empires), Naomi Romero, Rosa Colón (Soda Pop Comics), Daniel Irizarri Oquendo (Madre de Dios), Héctor González Rodríguez III, among many others, are all putting a much stronger and diverse Latinx narrative together, and succeeding at it.

If anyone questions the extent of our presence in comics before the current generation of Latinx creators, the mention of the Hernández brothers, Fabián Nicieza, George Pérez, Kenneth Rocafort (Superman, Sideways, The Ultimates), Gabriel Rodríguez (Locke & Key), Alejandro Jodorowski (Incal), and Humberto Ramos (Crimson, The Amazing Spider-Man) could dispel of the notion that we weren’t here before. These creators need to be included in the Latinx comics narrative. Their identities are important given they establish a sense of creative vision, visual language, influence, and structure to the culture of comics as a whole. We are very much a part of comics continuity.

The Latinx creators I’ve mentioned are all part of a narrative that is now taking shape as a bigger and more present component in the history of comics on a mainstream level. That it is scattered is an industry-wide problem that must be intentionally addressed. There is a before, there is a now, and there is definitely an after. It’s about time we get that story straight.

Can you define what is meant by Latinx creators? For instance, what origin countries are included? And is this topic strictly referring to creators who live (or lived) in the U.S.? I would think, for example, that Sergio Aragonés counts, but I don’t see his name mentioned anywhere here, and he’s about as big and famous a Spanish-origin comics creator as you can find in the U.S.

While he can probably get away with calling himself Latinx cause he grew up in Mexico he was born in Spain so he’s a Spaniard.

Enough with the Latinx bs. People en la comunidad don’t use or appreciate that term…

I am pleased beyond measure that this year I get to introduce English-speaking audiences to two different projects we have cooking at Pulp 2.0:

First is a B&W collection of the classic horror comics of Spain’s Joan Boix (The Phantom, Jonathan Struppy) that have never been seen here in the USA. We are in the process of translating them now…

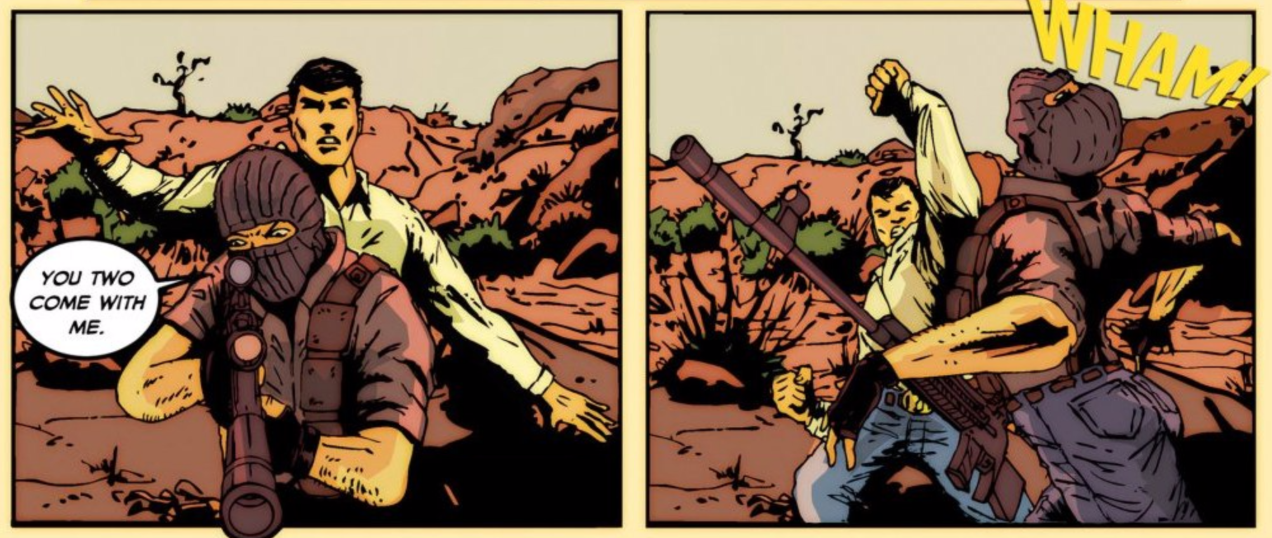

Second is both a series of 5 issues, and a collection of KILLER – the Chilean spy comic from the pen of German Gabler (Chile’s JAMES BOND 007 comics) which “stars” Charles Bronson. This was a comic that came out in 1974 during the government’s crackdown on literature. The ten issues are being translated now and will be re-released in Spanish speaking markets as well. KILLER is a two-fisted spy action adventure.

Both projects are comics that deserve to be better known in the US, and we’re proud to be able to showcase this “latin pulp.”

“Latinxs”? When did that term start being used? I need an app to help keep up with all of these made up labels/names.

Comments are closed.