Thirty years ago, Robin was killed.

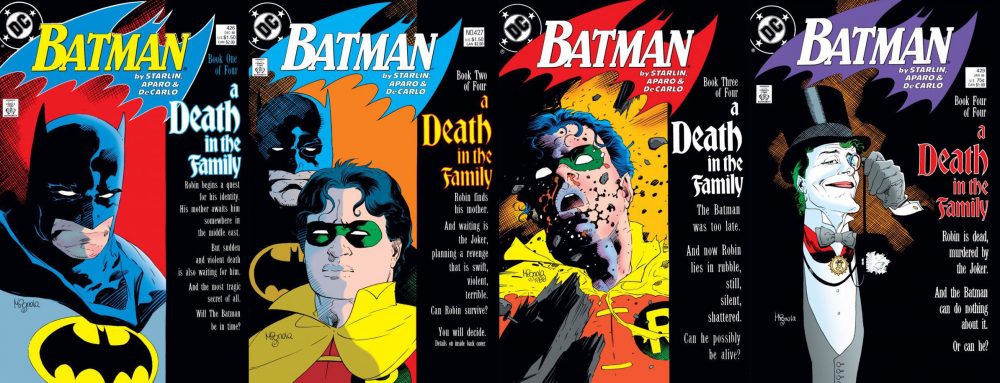

Sure, it was The Joker who, in the pages of the “A Death in the Family” storyline, wielded the crowbar and planted the bomb that ended Robin’s life, but the plot to snuff out Batman’s sidekick was far more insidious than any supervillain’s scheme. It began with an unpopular replacement, an ill-advised revamp, and three people having a casual discussion at an editorial retreat; it ended with a 900-number call-in vote system, and over 10,000 reader participants who ultimately voted by a narrow margin to kill the boy wonder. The story, and the manner in which it was executed, were instantly controversial, making national headlines and capturing the interest of non-comic readers who knew Robin best as Burt Ward’s “Holy _____”-spouting do-gooder.

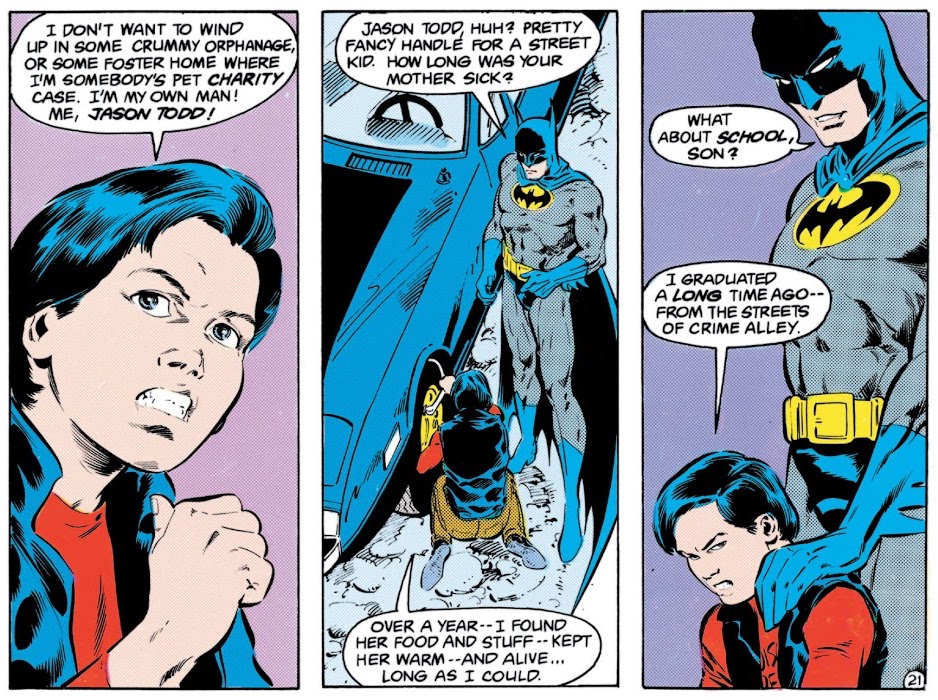

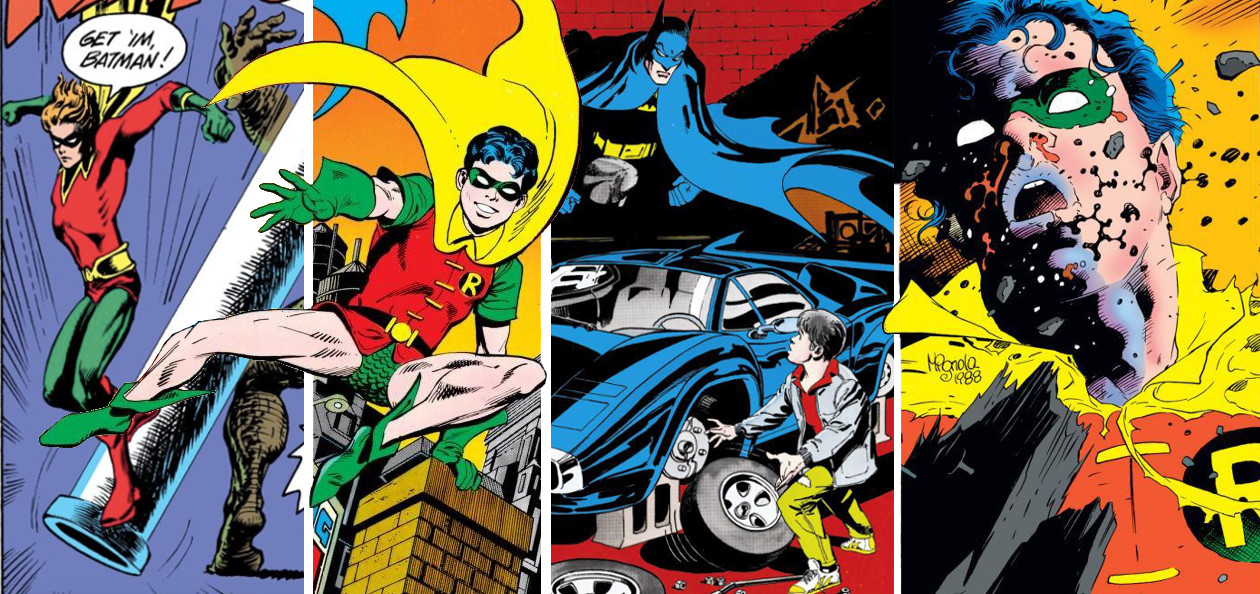

Of course, the Robin who died wasn’t the Robin the public-at-large knew. In 1983, following Dick Grayson’s evolution into Nightwing, a young boy named Jason Todd became the second character to take up the mantle of Batman’s faithful sidekick. As the junior half of the Dynamic Duo, Jason faced off against all manner of villains, but five years and two different origins later, Jason met his end in Batman #428.

Jason Todd’s death has loomed large in the mythos of the Dark Knight ever since, even after the character’s return to life in 2005. The call-in vote to determine whether Jason lived or died has been parodied and pilloried numerous times, and never repeated. But what sequence of events led to the killing of a boy wonder? Utilizing dozens of new and existing interviews with nearly every creator who worked on the character, The Beat presents an oral history of the second Robin, Jason Todd, from creation to “A Death in the Family.”

Part I: The Replacement Robin

The year was 1982, and Robin was at a crossroads. DC had a smash hit on their hands in the form of Marv Wolfman and George Pérez’s New Teen Titans. The updated version of the classic sidekick team featured Robin—that is, the original Robin, Dick Grayson, now a Teen Wonder—in a prominent role as the team’s leader. There was just one problem: Batman still needed his sidekick.

Gerry Conway (writer, Batman and Detective Comics, 1981-1983): I always felt that Batman worked really well with a sidekick like Robin. My interest in the character was the version of Batman as a detective, the version of Batman as a guardian of Gotham. This was prior, I believe, to the deep-dive into the “dark knight” kind of concept of Batman, so, for that end, the idea of a younger sidekick who could bring out a little more levity in the character seemed useful. But Dick Grayson as a character had grown into a young adult and was integral to the Teen Titans series, and had his own life and his own storylines that were developing separately from Batman, and [he] couldn’t really play that secondary role that I was interested in exploring.1

Marv Wolfman (writer/co-creator, New Teen Titans, 1980-1995): We had aged [Dick], we had made him a real leader, we had done a whole bunch of things with him, and I didn’t want to give up Dick Grayson.2

George Pérez (artist/co-creator, New Teen Titans, 1980-1984): Marv was being complimented on his characterization, I was being complimented on making Robin look like an adult at last. Yet we couldn’t do anything more than just maintain a certain façade; we’d just made a very virile Robin, but couldn’t do anything with his personality or his basic character. That was all the responsibility of whoever was writing Batman.3

Conway: I felt that it was a useful device to replace the character with a younger version that could emulate some of the usefulness of a ward that Robin had played, that role that Robin had played in prior incarnations. I made the pitch, and it was generally considered to be a pretty good idea because Marv wanted to focus more on Dick Grayson’s relationship with characters like Starfire and the Teen Titans in general, and developing that into a separate character called ‘Nightwing’ made a lot of sense because the baggage that the Robin character carried was as this kind of sidekick kid character, and Marv wanted to treat him more as a young adult. So it worked for [Marv] and it worked, I think, for Batman.1

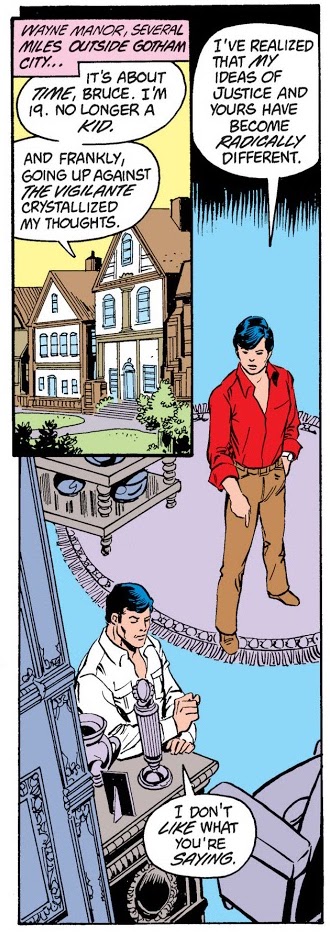

Pérez: I was called into a meeting. [Incoming Batman writer] Doug Moench, Marv Wolfman, [editor] Len Wein, myself, and [DC Vice President/Executive Editor] Dick Giordano all sat down and talked about the new sidekick. The one thing we suggested, but never thought we’d get, was to simply make Jason Todd become Robin. Give him the costume, make him the new Robin and just let Dick Grayson become someone else. We didn’t think they would really accept that; [Laughs] at least, not readily, because Dick Grayson had been Robin for almost 43 years! Dick Giordano said ‘Let’s go with it!’ Since Dick Grayson has been established as being 19, and Batman has been established as 29 (the way Superman and all the other male characters are), suddenly the man-boy relationships between men 29 and 19 did not work; they were two men.3

Wolfman: It was something we had been leading to, but we never expected we’d have permission to remove him from the Batman continuity whatsoever and this gave us a chance to actually fulfill the story that we had been working towards. George’s artwork was playing him at about 21. I was writing him about the same age. We’d already been having long stories about Dick Grayson breaking up with Batman, not being part of the Batman thing, so it fit perfectly that he would want to change. Also, he hated those stupid green shorts. [Laughs] Just utterly… It’s so cold in Gotham in the winter and Batman’s totally dressed in armor. So [they] thought that was a great idea and they went off and created Jason Todd, and I got to play with Dick Grayson and finally make him his own person.2

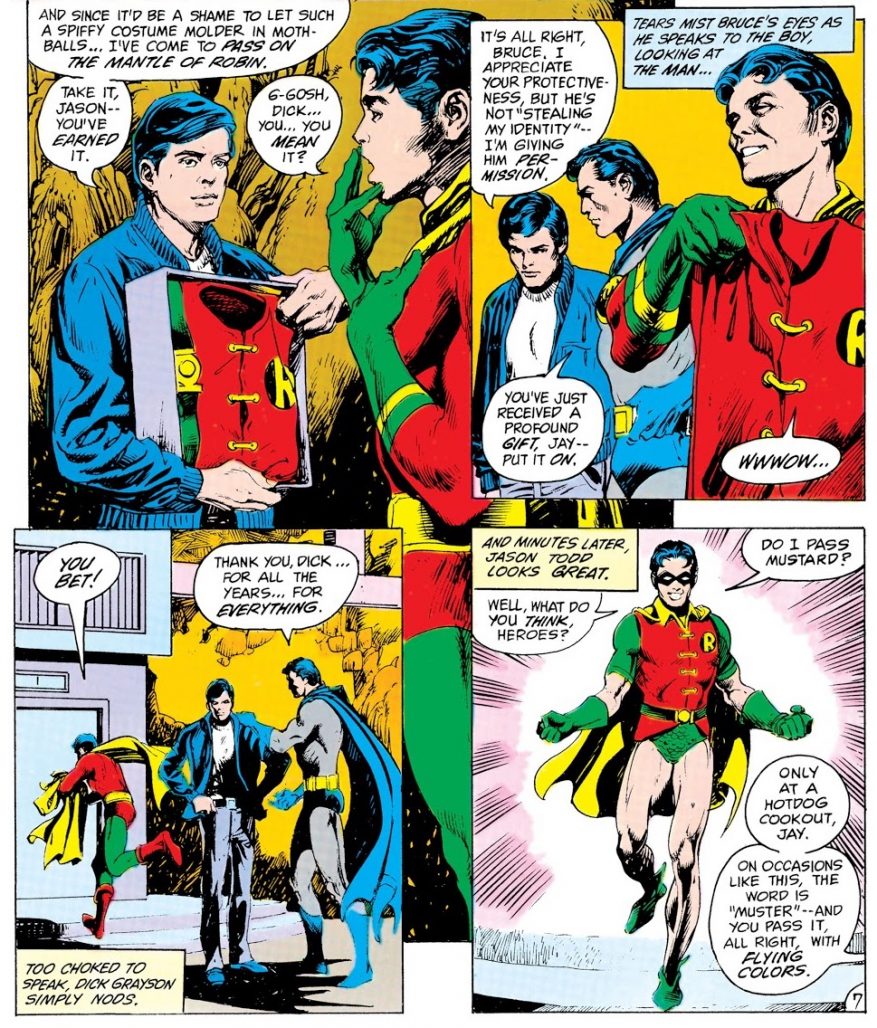

Jason Todd made his first appearance in Batman #357. The red-headed Jason and his parents, Joe and Trina Todd, were a trio of circus acrobats known as the Flying Todds. After Trina and Joe stumble upon the secret of Batman and Robin’s true identities, the couple agrees to help the dynamic duo in investigating a new crimelord, Killer Croc, who was running a protection scheme on the travelling circus for which the Flying Todds perform. The investigation ends with the elder Todds dead at Croc’s hands, and Bruce Wayne taking in an orphaned Jason, who had himself learned Batman’s true identity on his own and, wearing a costume cobbled together from Dick Grayson’s old circus attire, aided Batman, Robin, and Batgirl in defeating Croc.

Denny O’Neil (writer, Batman/Detective Comics, 1970-1980; Batman group editor, 1986-2000): [Jason Todd] was invented by Gerry Conway in an origin that is a virtual duplication of Dick Grayson’s Robin origin. I doubt they were worried about creating a new character. I think they thought, “We’ve got to have a Robin in the series so let’s go with the tried and true. This Robin has worked for so many years, so let’s do him again.”4

Conway: It may seem lazy, but I thought that there was a certain symmetry to having a similar [origin] story to Dick Grayson’s character. There’s something about the ‘tragic family loss’ that is shared by both Batman and his protégé that ties them together. So having Jason come from a similar backstory as Dick Grayson seemed like a natural play for me. Other people might consider that a lazy decision, but for me it was it was a necessary one because I wanted to embrace that mythology. And it provides a continuity between the two characters, so that there’s a connection to the larger mythos, that the throughline goes from Batman, to Robin, to Robin.1

Pérez: The only suggestion I had was to establish Jason Todd as a blonde or a redhead; obviously, they [wrote] their way around that! [Laughs]3

Conway: I don’t think [making Jason Robin] was a popular move, but Batman was in transition in that era, too, so we weren’t really quite sure what was going to work for Batman. And that was part of the reason that the “dark knight” [interpretation] was done, I believe, was because they were trying to come up with some approach to the character that would be fresh for a modern readership.1

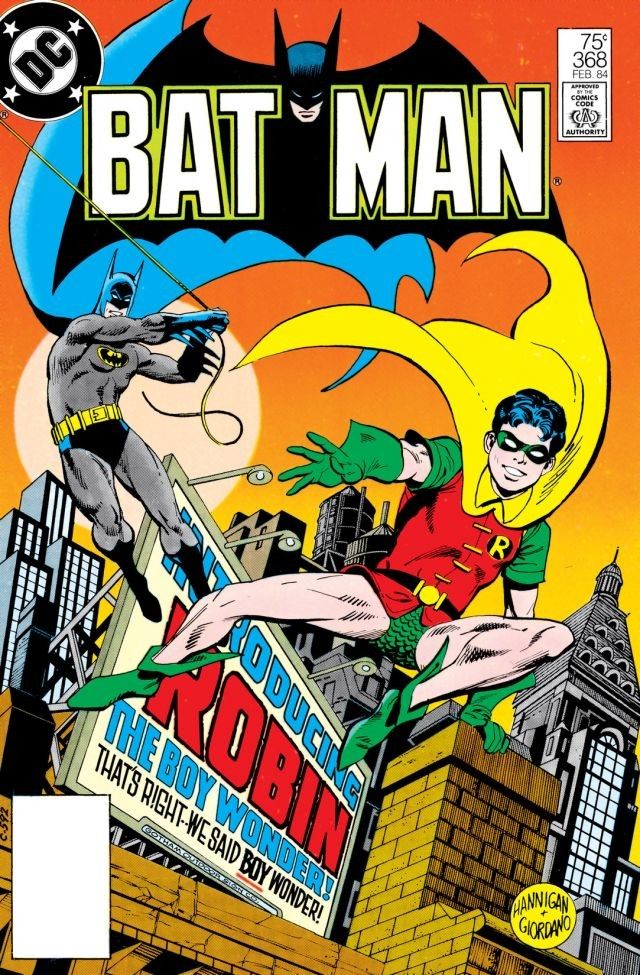

Gerry Conway stepped away from the Batman books at the end of Jason’s introductory storyline, and writer Doug Moench inherited the task of further developing Jason Todd, first as Bruce Wayne’s new ward, and later as Robin. In February of 1984, the same month that saw Dick Grayson formally retires from the identity of Robin in New Teen Titans #39, Batman #368 officially welcomed Jason Todd as the new boy wonder. In the issue, Grayson hands his old costume and title of Robin over to Jason (who would start dyeing his red hair black in order to maintain continuity).

Over the next nearly three years, Batman and Robin would square off against most of the major players in the caped crusader’s rogues gallery, as well as against new foes like Nocturna (a foil for both Batman and Bruce Wayne who attempted to adopt Jason Todd herself), the Night Thief, and Black Mask. Jason would gain a love interest in the form of classmate Rena; develop a unique partnership with Gotham City Detective Harvey Bullock; join the New Teen Titans himself at a time when Nightwing was in the thrall of Brother Blood; and confront bullies and drug dealers at his school. Moench’s initial run writing the Bat-titles, and Len Wein’s time editing the line, both came to a close with Batman #400.

Part II: Reinventing Robin

1986 was a year of massive change for DC Comics. The conclusion of the 12-part Crisis on Infinite Earths event series in March had resulted in a single, streamlined DC Universe, and an opportunity to update and reboot the fifty-year histories of the company’s characters. October of that year also saw an editorial change in the Bat-offices, as former Batman and Detective Comics writer Denny O’Neil stepped into the role of overseeing the Batman titles. O’Neil’s approach to Batman—and to Robin—differed from that of his predecessors.

O’Neil: There was a time right before I took over as Batman editor when he seemed to be much closer to a family man, much closer to a nice guy. He seemed to have a love life and he seemed to be very paternal towards Robin. My version is a lot nastier than that. He has a lot more edge to him.4

Max Allan Collins (writer, Batman, 1986-1987): I was writing the Dick Tracy comic strip and attracting some nice attention. Denny O’Neil liked my work there, and gave me a two-issue try-out, then hired me. I don’t personally care for an overly dark Batman. I’m not after camp, but there should be some humor. A “realistic” Batman is an absurdity.5

Mike W. Barr (writer, Detective Comics, 1986-1987): A lot of people don’t see the need for Robin. A couple of writers who really ought to know better have said that Batman does not need Robin. I have always maintained that Robin is an integral part of the strip and an integral part of the series’ longevity. I always tried to make sure that the logo in the Detective Comics stories was always the classic “Batman with Robin, the Boy Wonder” logo, because Robin, to me, is part of the story.6

Collins: I was specifically asked to reboot and introduce a new Robin, calling him Jason Todd (which was already his name, I believe.) I would have greatly preferred using Dick Grayson, as a longtime Batman fan.5

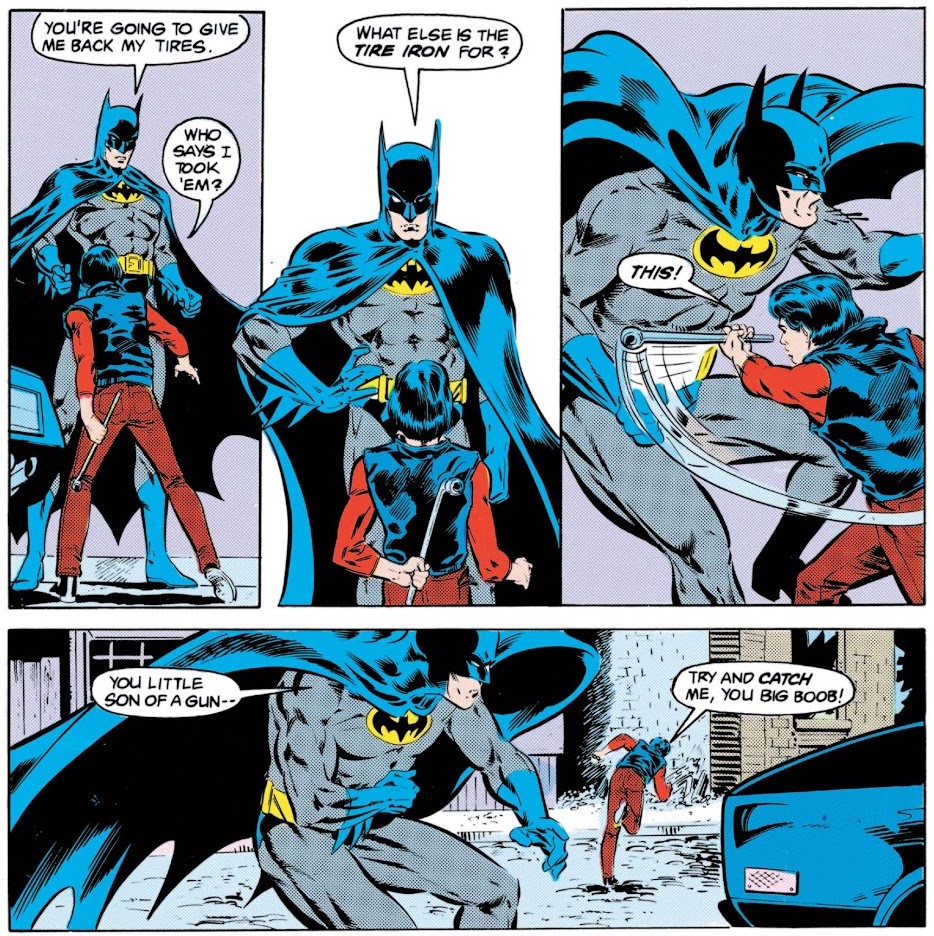

Batman #408 began “Batman: The New Adventures”, and a new origin story for Jason Todd written by Collins. After Dick Grayson is shot by The Joker, Batman forbids him from continuing on as Robin. Dick moves out, and, some time later, Batman catches a young homeless boy named Jason Todd stealing the tires off of the Batmobile. After Jason helps him in shutting down a ‘crime school’ in Crime Alley, Batman takes the boy in, and after six months of training Jason makes his debut as the new Robin in a case involving Two-Face – who, unbeknownst to him, had killed Willis Todd, Jason’s father and a former member of Two-Face’s gang. By the end of Batman #411, Two-Face was defeated and Jason had seemingly come to terms with his father’s death and settled into the role of Batman’s junior partner.

Collins: My first four stories are essentially “Robin: Year One.” And that’s how I pitched it and in fact I requested that it be called “Robin: Year One” and that it be a mini-series within the book. That was dismissed, for whatever reason, as not being feasible.7

Barr: I think the darker aspects to Jason Todd with his origin and the Two-Face relationship came in a little later. I reference those in the Two-Face story that [artist] Jim Baikie did at the end of my run on Detective, but I don’t think that was in there at the beginning.6

Collins: I believe the street kid thing was my idea, the notion being that Batman/Bruce Wayne did not want responsibility for putting Dick Grayson in harm’s way anymore, but this new street kid was already in harm’s way and heading toward the wrong road. So taking him on (and it was a gradual decision) made sense.

Collins: That was pre-Internet, and I had little contact with Denny. He seems to have thought I wasn’t doing a dark enough version of [Batman], possibly because my own comic book with Terry Beatty, Ms. Tree, was violent and even grim at times. We had a few phone calls but mostly we seem to have stayed out of each other’s way, rather than collaborating. I really respected his work, and he respected my work in general, although I learned late in the game he was at least somewhat disappointed in my Batman work.5

Dan Raspler (assistant editor/associate editor to Denny O’Neil, 1988-1990): Denny is a complicated fellow. He had expectations of guys, and he would expect them to act professionally, and when they wouldn’t he would be disappointed, but he wouldn’t have them change it. He would say, ‘Well, I’m not going to hold their hand.’8

Collins: I was supposed to write a full year but became disenchanted with the rotating artists and a certain amount of editorial tampering.5

O’Neil: That was, for me as an editor, a learning experience, because we made mistakes. Nobody had ever done what we were doing before so I don’t think we ought to wear hairshirts about this, but I carry around a lot of regret for the things that I did wrong when I was professionally involved, and we could’ve done better with that story.9

Collins quit the Batman title after issue #413, and the following month’s Detective Comics #581 was Barr’s final issue as well. Jim Starlin and Jim Aparo were tapped as the new Batman creative team, while Alan Grant and John Wagner picked up the writing chores on Detective alongside a young artist named Norm Breyfogle. Neither team was particularly enthusiastic about the boy wonder.

Jim Starlin (writer, Batman, 1987-1988): I tried to avoid using [Robin] as much as I could. In most of my early Batman stories, he doesn’t appear. Eventually Denny asked me to do a specific Robin story, which I did, and I guess it went over fairly well from what I understand. But I wasn’t crazy at Robin.10

Alan Grant (writer, Detective Comics, 1988-1990): John [Wagner] and I just preferred—felt more comfortable with—our own characters. I think it was after that first year on Detective that Denny told me he was getting an increasing number of letters from readers who wanted to see the established characters back in print.11

Starlin: I thought that going out and fighting crime in a grey and black outfit while you send out a kid in primary colors was kind of like child abuse. So when I started working on Batman, I was always leaving Robin out of the stories, and Denny O’Neil who is the editor finally said, ‘You gotta put [Robin] in.’12

Raspler: Denny wasn’t really interested in comics continuity, and he didn’t like superheroes. And if you read his work, you see his influence was really a pushing away from the conventions at the time—it was growing old, that sort of Golden Age-y, Silver Age-y stuff, and Denny sort of modernized it, and he never stopped feeling that way. Jim Starlin’s Batman appealed to Denny. It was a little more ‘down to Earth.’8

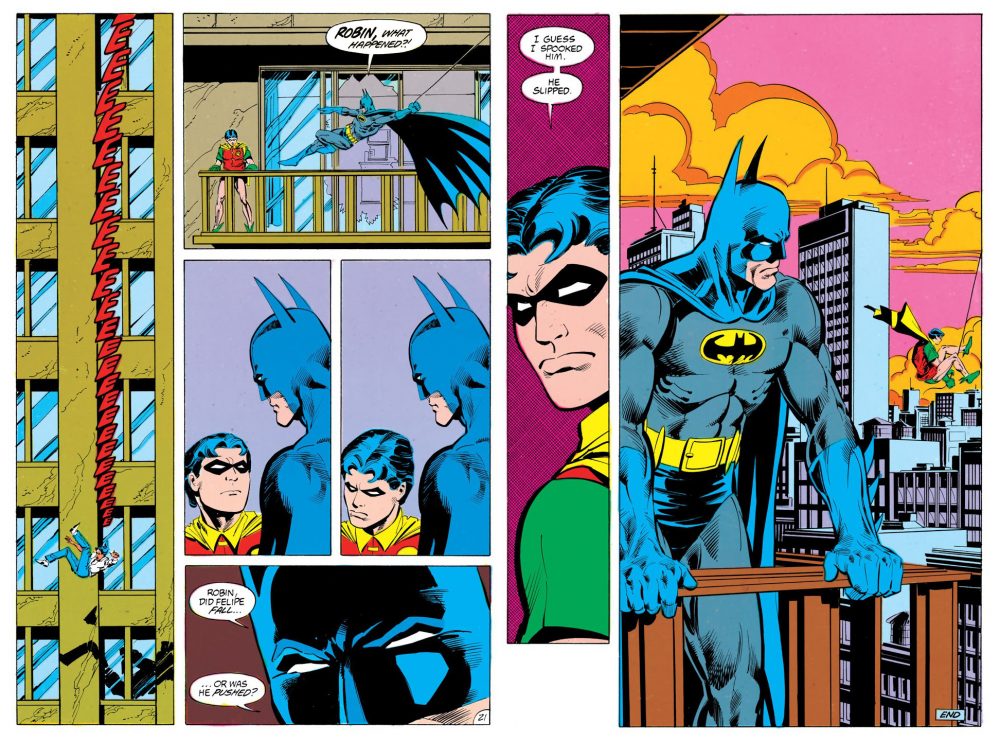

Starlin: In the one Batman issue I wrote with Robin featured, I had him do something underhanded, as I recall. Denny had told me that the character was very unpopular with fans, so I decided to play on that dislike.13

Raspler: Nobody liked Robin at the time. For a while Robin was not—it didn’t make sense in comics. Comics were darkening, and so having the kid was just, it was silly, and even at the time I kind of didn’t. Now Robin is my favorite all-time character, but at the time when I was twenty-whatever, I accepted kicking Robin out, the short pants and all the rest of it.8

O’Neil: They did hate him. I don’t know if it was fan craziness—maybe they saw him as usurping Dick Grayson’s position. Some of the mail response indicated that this was at least on some people’s minds. I think this is taking the whole thing entirely too seriously. It may be that something was working in the writers’ minds, probably on a subconscious level. They made the little brat a little bit more disagreeable than his predecessor had been. He did become unlikeable and that was not any doing of mine. But we became aware that he was not very popular. Once we became aware of that, of course, we began playing to it.4

Part III: A Death in the Family

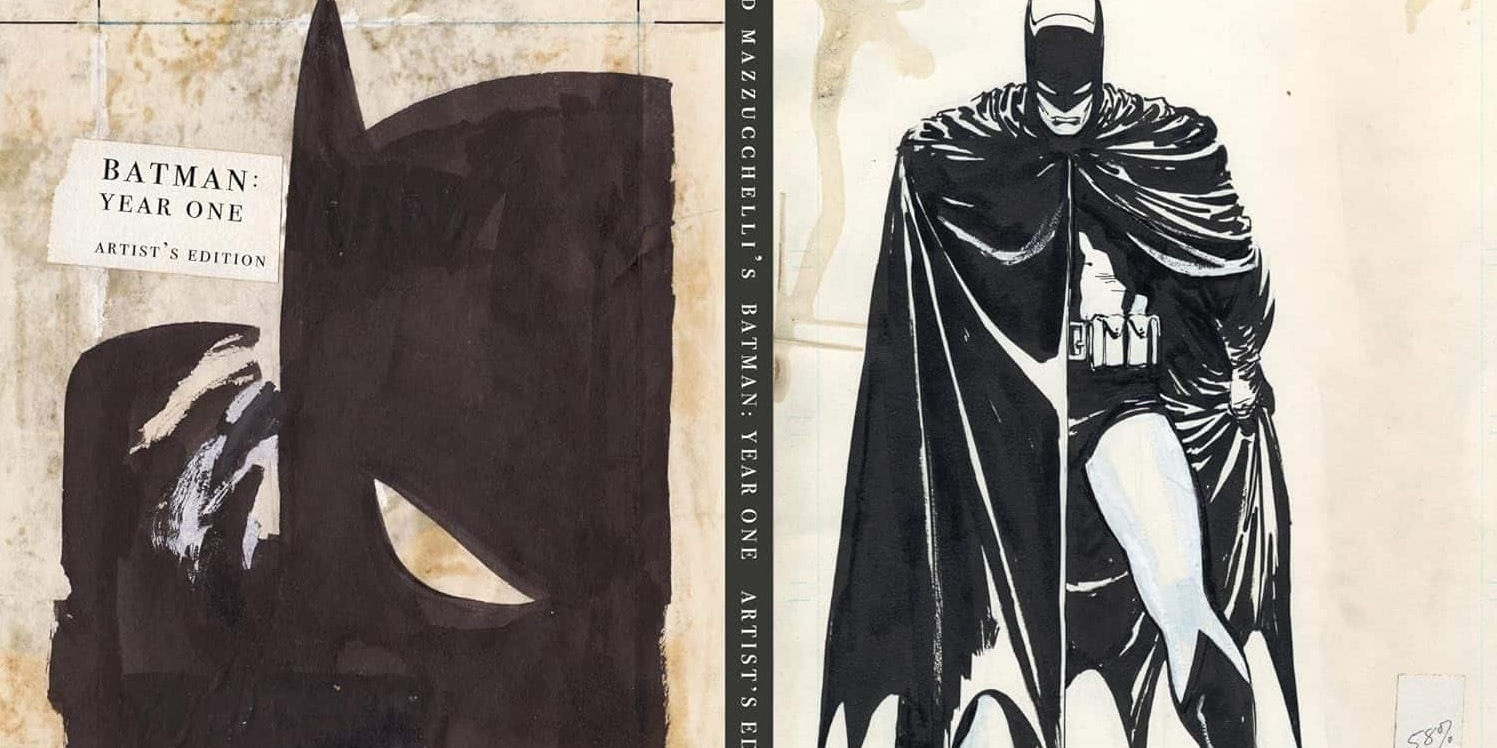

As the Batman titles went into 1988, nearly everything was going right. Average monthly sales for the main Batman title were at their highest level since the early ‘70s, buoyed no doubt by the successes of The Dark Knight Returns and “Year One” storylines. A feature film was in development and planned for release the following year. A new wave of Batmania was about to begin. And, unbeknownst to readers, Jason Todd’s future as Robin was about to be placed in their hands.

O’Neil: We knew we had a problem with Robin. It was a case of something you hear about and seldom encounter: a character taking on a life of his own. Maybe I should have been a more hands-on editor but it just kind of slipped past us and all of a sudden we had this disagreeable little snot and I thought we either had to give him a massive personality change or write him out of the series.14

Starlin: At that time, DC had this idea that they were gonna do an AIDS education book, and so they put a box out and wanted everybody to put in suggestions of who should contract AIDS and perish in the comics. I stuffed it with Robin. They realized it was all my handwriting so they ended up throwing all my things out. About six months later, Denny came up with this idea of the call-in thing.15

Jenette Kahn (publisher, DC Comics, 1976-1989; president, 1981-2003; editor-in-chief, 1989-2003) : Many of our readers were unhappy with Jason Todd. We weren’t certain why or how widespread the discontent was, but we wanted to address it. Rather than autocratically write Jason out of the comics and bring in a new Robin, we thought we’d let our readers weigh in.16

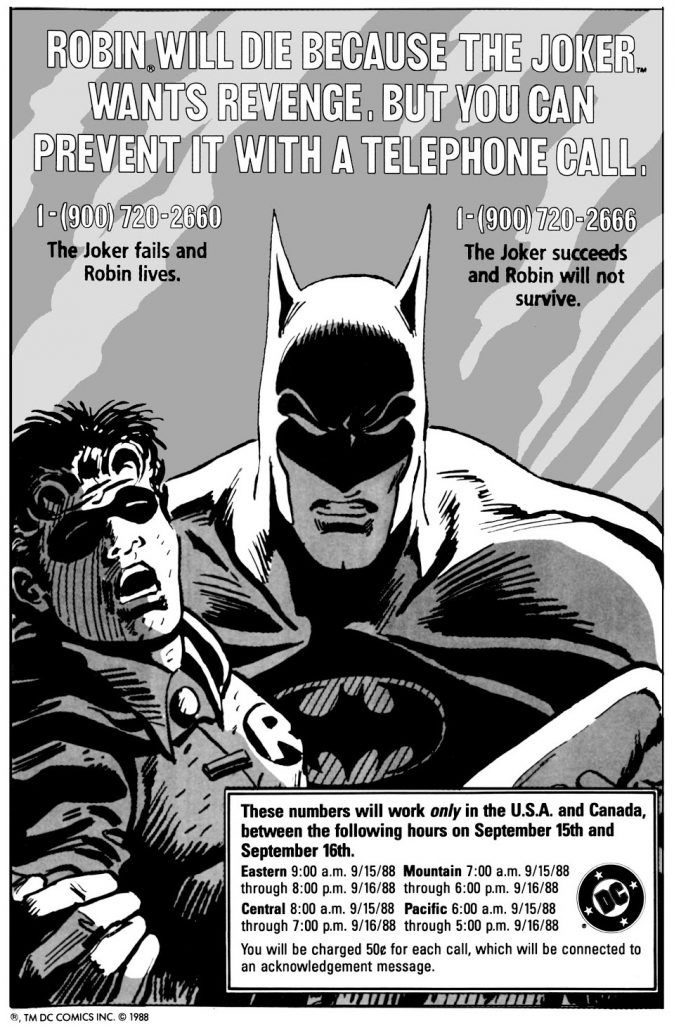

O’Neil: We were sitting around brainstorming at an editorial retreat. I mentioned the 900-number that had been used by Saturday Night Live and one or two other places, and Jenette thought it was an interesting idea. We began to discuss how we could use it. I guess I came up with killing somebody and the logical candidate to be in peril was Jason, because we had reason to believe that he wasn’t that popular anyway. It was a big enough stunt that we couldn’t do it with a minor character. If we were going to do it, it had to be a big, significant change. I don’t think it would have had the impact we wanted if we had created a character and built him up and then put him in danger. It had to be something dramatic. This was the first time we were going to have real reader participation in comic books.4

Kahn: These days, it’s commonplace for viewers to phone in and vote contestants on or off a show, but 30 years ago, it was a radical idea to have our readers determine Jason’s fate.16

O’Neil: Then, I confess, it seemed like a great caper. It had that value to us. Like wow, what a neat thing to do.4 And so somebody came up with the idea of letting the readers decide and Jenette went to work making that work with the phone company.14

Bruce Bristow (Former Vice President, Sales and Marketing, DC Comics): In a lot of ways, I think the setting up of the phone number was the most difficult part of this whole thing.17

Paul Levitz (Executive Vice President, DC Comics, 1984-1989; Executive Vice President and Publisher, 1989-2002; President and Publisher, 2002-2009): The last time we had a special phone number, the phone company made us cancel the number. This was about [1980], and it was an ‘800’ number. They told us that there were so many incoming calls that it burned up the lines.17

John Pope (Former Sales Manager, DC Comics): Each time I call[ed AT&T], a new person had been assigned to the service. I started calling on October 1st [1987]. By mid-December I was still trying to firm things up. It wasn’t until the middle of March that we had a contract in hand and the phone numbers reserved.17

Starlin: [Denny] approached me and said, ‘You think we can write up a thing where we maybe kill off Robin like you’ve been lobbying for for the last six months?’ and I went ‘oh, sure.’15 I chose The Joker because of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns. In there, it’s revealed that The Joker killed Jason.13

Frank Miller (writer/artist, The Dark Knight Returns): It was hinted at in “Dark Knight [Returns]”—what happened to Jason was supposed to be the reason that Batman retired in the first place. How it happened was also hinted at—it was meant to be something haunting around the edges. It was just this further edge to the darkness of Batman.18

Raspler: It was my idea to put [artist Mike] Mignola on the covers. I think I colored the covers. They’re very simple colors. [Or] I think he might’ve colored the covers and then I did the trade paperback.8

Starlin wrote scripts for a six-part storyline, to be called “A Death in the Family;” the decision was later made to combine parts 1 and 2 into one issue, and parts 3 and 4 into the next issue.

O’Neil: The whole idea was reader participation, so speeding up the story-telling process by publishing double-issues seemed in the spirit of it all.17

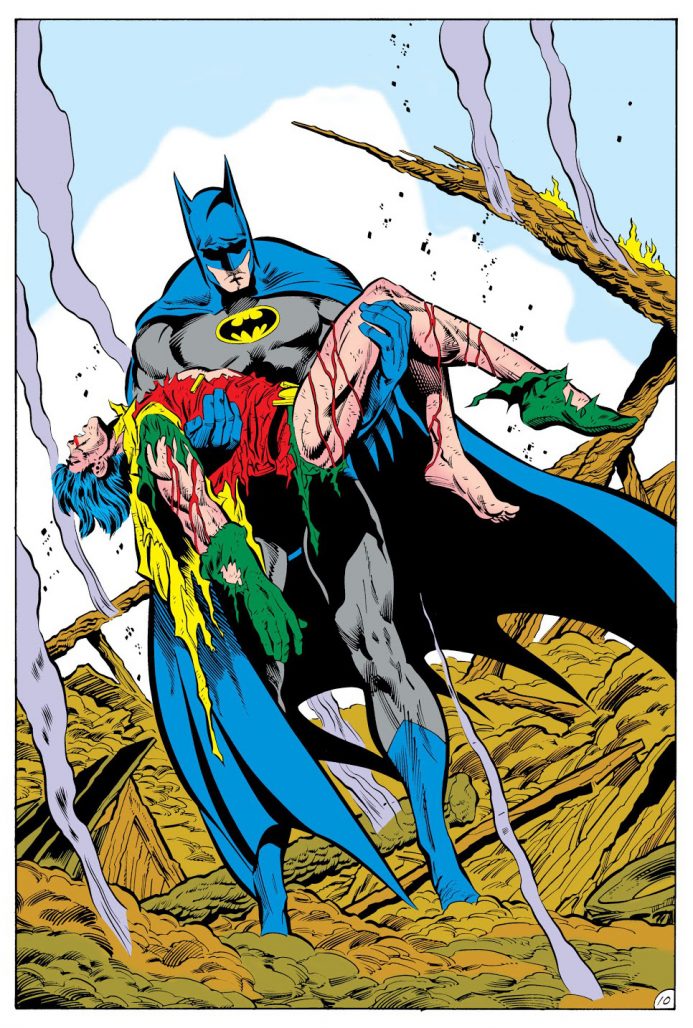

“A Death in the Family” kicked off with the double-sized Batman #426, by Starlin and artists Jim Aparo, Mike DeCarlo, and Adrienne Roy, which shipped on August 23rd, 1988. Batman #427, also double-sized, shipped two weeks later on September 6th. The issue ended with Jason double-crossed by his recently-discovered birth mother, badly beaten with a crowbar by The Joker, and (along with his mother) locked in a room with a ticking bomb set by The Joker. Batman arrives on the scene just as the building explodes. The inside back cover to Batman #427 included details for the reader call-in—one 900-number to save Jason, and another to vote for his demise.

Kahn: Although rumor has it that we had rigged the outcome and already decided that Jason would die, in truth we had two different endings drawn and ready to go depending on the vote of our readers.16

O’Neil: Two Batman #428s were prepared. It really could have gone either way. We prepared two choices of balloons. We had alternate panels. We had everything set up so that the two outcomes could be accomplished with a minimum of changes. We prepared for either situation.17

Raspler: Jim wrote two alternate endings for the fourth issue, I guess, or the sixth issue. It might’ve been three pages or something like that, and a number of the pages had static images so that it was easy to shift, it was easier to swap them in at the last second. Jim Aparo might have doubled up four pages total. It was very minimal. If you look at the story and imagine, ‘What would be necessary to change if he had lived’, it wouldn’t be hard to figure out the panels. It would be a minimal number of panels.8

O’Neil: I cast my vote for Jason—I very much wanted Robin to survive. I don’t ever intentionally make my own life more complicated, and the death of Robin would complicate my editorial chores tremendously.17

Starlin: I didn’t even call in once.10 I was off in Mexico when the voting took place.15

O’Neil: My assistant, Dan Raspler, checked the progress of the vote every 90 minutes, beginning Thursday morning, September 15th. He’d punch in a code and a computer voice would recite the most up-to-the-minute count. Either Dan or I continued checking throughout the day on Thursday and then again on Friday, September 16th. For most of the voting, it was very close.17 Dick Giordano and I had different opinions about [it]. He thought they would not kill the kid. I thought the readers would do it just to see if we would actually go through with it.14

Voting to decide the fate of Jason Todd was open for 35 hours, from 9AM Eastern on Thursday, September 15th, until 8PM Eastern on Friday, September 16th. The decision, it turned out, would come down to a mere 72 votes.

O’Neil: My wife, Marifran, came up to the office at 6PM to keep Dan and me company. At 8:30PM, after even Dan had left, I got the final tally: 5,271 for Robin, but 5,343 against. I was disappointed but not terribly surprised. I’d originally planned to throw a party that Friday night. But, as it became clear that we had such a Big Deal here—that people were truly interested in Robin’s fate—we decided that revealing the outcome before shipping the book would lessen the dramatic impact. We became like the CIA. Everything was on a ‘need-to-know’ basis.17

Bob Rozakis (Production Director, DC Comics, 1981-1998): We had Jim Aparo’s alternate pencils for all the scenes in the production department. I had the colorist, Adrienne Roy, color around the pivotal scenes. I kept both versions visible to my staff—but one person and one person only was charged with maintaining the secrecy here. Steve Bove took the real Batman #428 issue home and did all the production work in the privacy of his apartment. He returned the pages in a sealed envelope, and we shipped that envelope directly to the color separators. I told the separator that he had to maintain the secrecy. I promised him free comics if he could keep this quiet. I don’t know what he did, but I guess he divided the pages up in such a way that no one at Chemical Color realized what he or she was working on.17

O’Neil: I honored the commitment to such an extent that I didn’t even tell my wife. She knows me well enough that I suspect she read my body language after the voting was over, though. I didn’t even tell Jim Aparo or Jim Starlin—but Jim Starlin guessed.17

Starlin: I didn’t find out about it until I came back [from Mexico] and found out that, just as I expected, my ghoulish little fans voted him dead. But by a much smaller margin than I’d imagined. It was only like 72 votes out of 10,000, so statistically it was next to nothing.15

Grant: The whole thing came as a surprise to me, though I may have been told shortly before it happened. There were rumours at the time of anti-Jason fans using automatic dialing machines to record dozens or even hundreds of votes, but I have no idea if that’s true.11

O’Neil: It turns out, if what I heard is true, that a lawyer programmed his Macintosh to dial the killing number every few minutes. It was only 85 votes out of over 10,000 and that may have made the difference. I have never been able to verify that story but it was a squeaker any way you look at it. And I’m like, “OK, this has been an interesting caper but it’s over and I’m gonna go home and have my weekend.”14

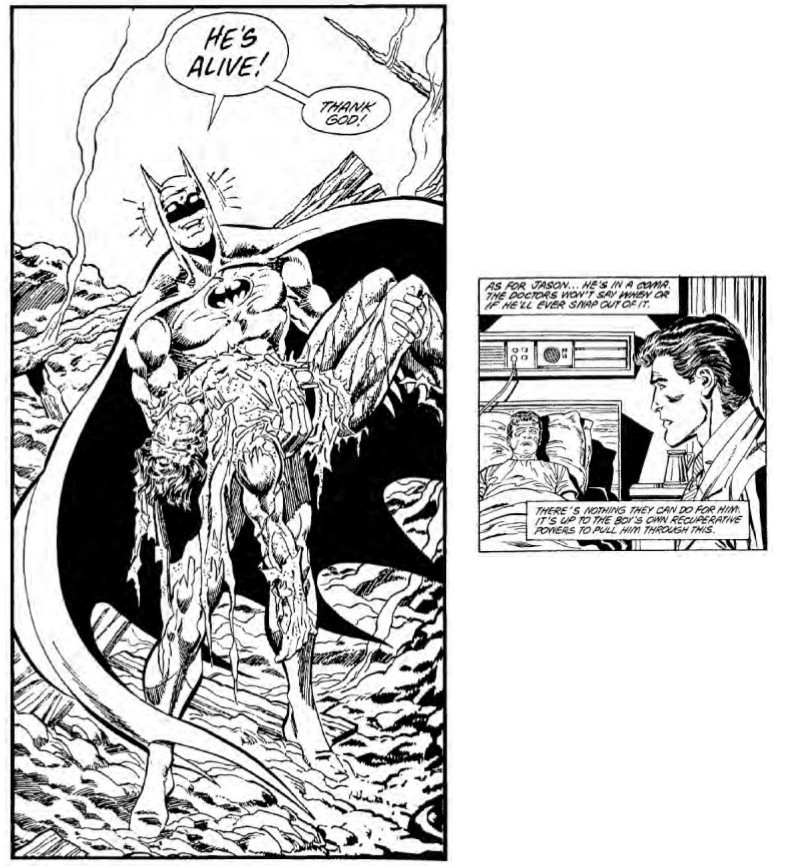

Batman #428, the third part of “A Death in the Family” shipped on October 18th, 1988. The issue opened with Batman surveying the wreckage of the bombed warehouse and, as decreed by fans, discovering Jason had died in the warehouse explosion. Public reaction to the story was swift.

O’Neil: I spent three days doing nothing but talking on the radio. I thought it would get us some ink here and there and maybe a couple of radio interviews. I had no idea—nor did anyone else—it would have the effect it did. Peggy [May], our publicity person, finally just said, “Stop, no more, we can’t do anymore,” or I would probably still be talking. She also nixed any television appearances. At the time, I wondered about that but now I am very glad she did, because there was a nasty backlash and I came to be very grateful that people could not associate my face with the guy who killed Robin.4

Raspler: [Jason] was unpopular. He was not a popular guy. Though there was some upswelling of support for him after we killed him. It was mostly negative, and a lot of that was a reaction to the controversy. I was a real company guy, so I couldn’t really respond to anything at the time. I gave some interview, some local TV thing, and I kept referring to it as “The Stunt,” and afterward Paul Levitz comes up to me and says “Good job, but next time don’t call it a stunt,” and I said “Oh, yeah, right!”8

O’Neil: We got a lot of hate mail and hate phone calls after Batman #428.17 I got phone calls that ranged from “You bastard,” to tearful grandmothers saying, “My grandchild loved Robin and I don’t know what to tell him.” That broke my heart.4

Batman #429 concluded “A Death in the Family.” The issue shipped on November 29th, 1988, and saw Batman confront The Joker about Jason Todd’s murder. There would be no justice done by story’s end, as an injured Joker escaped from both Batman and Superman. After quick sellouts of the first three chapters of the story, a trade paperback edition of “A Death in the Family” was rushed out in time for Christmas, shipping on December 5th, less than a week after the conclusion of the story first hit stores.

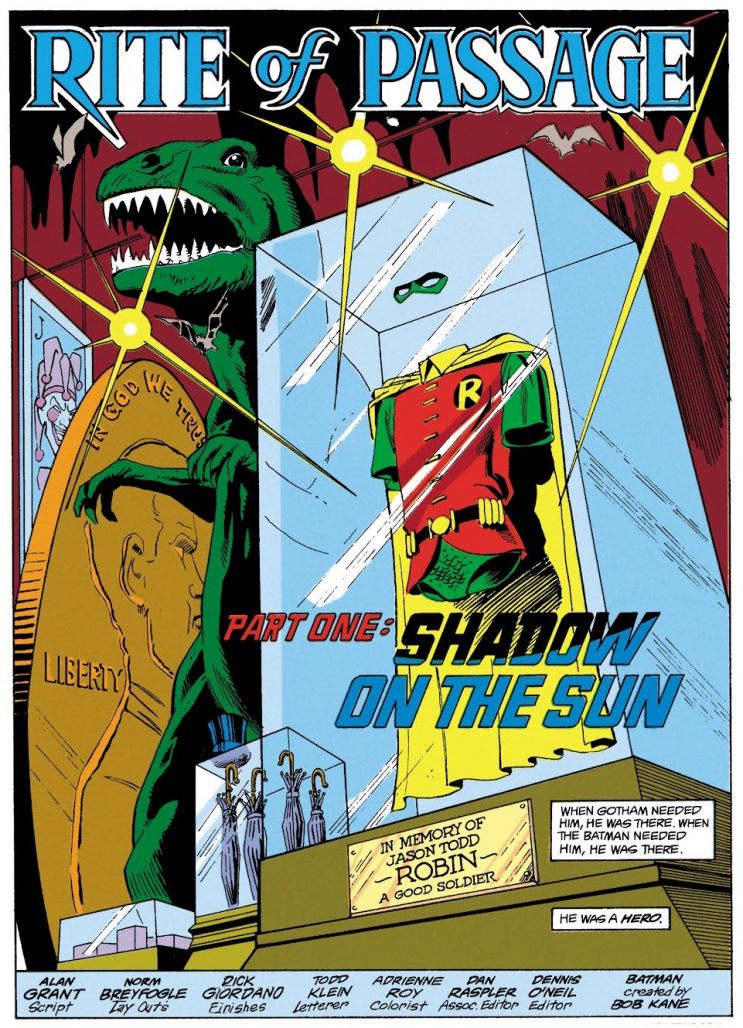

Part IV: The Legacy of Jason Todd

The death of Jason Todd became a major turning point in the Batman mythos. A memorial to the fallen Robin, a constant reminder to Batman of the cost of his crusade, has become a staple of the Batcave, as iconic as the giant penny or robot dinosaur. Between in-story events like the death of Robin and the paralysis of Barbara Gordon in The Killing Joke (which preceded “A Death in the Family” by mere months), and external influences like the smash success of 1989’s Batman film, Batman took a darker turn, evolving under Denny O’Neil’s editorial eye into the merciless avenger for justice that he is today. A new Robin would come along in the form of Tim Drake, but this would be a different type of Robin—more self-sufficient, more patient, more well-protected in an armored suit with a dark cape and long pants, and with stronger ties to the legacies of both Batman and the original Robin, Dick Grayson.

Outside of comics, Jason’s death has been featured in the animated Batman: Under the Red Hood movie, and “A Death in the Family” and the phone stunt were explicitly mentioned by Bat-Mite as one of Batman and The Joker’s greatest battles in the Batman: The Brave and the Bold episode “Emperor Joker.” The death of Robin at the hands of The Joker was also strongly hinted at in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice.

Jason Todd’s story didn’t end with his death, either. After a brief tease during Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee’s 2003 “Hush” storyline, the resurrected Jason was officially introduced by writer Judd Winick and artist Doug Mahnke as the villainous Red Hood in 2005’s Batman #635. Jason would continue to evolve, from villain to hero to anti-hero, and to find life outside of comics. The character’s death, and the manner in which it was executed, continues to capture people’s imaginations, with DC recently recreating the poll to determine Jason’s fate, this time as an online fan poll. As of this writing, just over 50,000 people have voted, with 73% in favor of Jason’s survival.

For the people who worked on the character, there’s no clear consensus on why Jason’s time as Robin turned out the way it did, and each reflects on their time with the second Robin differently.

Raspler: One day, should I find myself standing at the pearly gates—and I’m Jewish and I don’t believe in God—and St. Peter says to me, ‘Do you have anything you wish to say before we get into this?’ I think the first thing that pops into my mind is, ‘I was complicit in the cynical phone poll to kill Jason Todd.’ That weighs on my soul to this day. I feel like I could’ve done something, but I literally was just taking the votes. I was the assistant. I was just following orders! [Laughs]8

O’Neil: There’s a story that I’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of. I went to a deli on Fifth Avenue to buy a sandwich for lunch. And like Julie [Schwartz], I wore a little Batman pin. So the guy behind the counter leans over and he remarks on it. I mention who I am and he’s, “Hey, dis is da guy dat killed Robin!” This is what I mean. I just wanted a tuna fish sandwich. There was really a HUGE reaction! Now, this guy probably hadn’t seen a comic since he was a kid but to everybody, these characters have been all over the place!14

Conway: There was resistance to Jason which was ultimately I think why the vote went to kill him. Maybe if I had stayed on the book and had time to develop the character and create more individuality in the character rather than just a [Dick Grayson] clone, that might have been ameliorative.1

Barr: I’ve always felt that Robin was one of the basic ingredients to Batman’s longevity. I think if you didn’t have Robin in there that Batman’s constant quest for vengeance would’ve gotten a little tiresome after a while and the readers simply would’ve stopped reading. It’s funny because Frank Miller and I used to have a joke about Robin back in the ‘80s where he believed that Robins got killed almost every case and Batman would simply recruit more Robins. Batman would get a call from Commissioner Gordon that says, ‘The Joker’s taken over the water supply of Gotham City,’ and Batman would say, ‘That’s probably a five Robin job.’ [Laughs]9

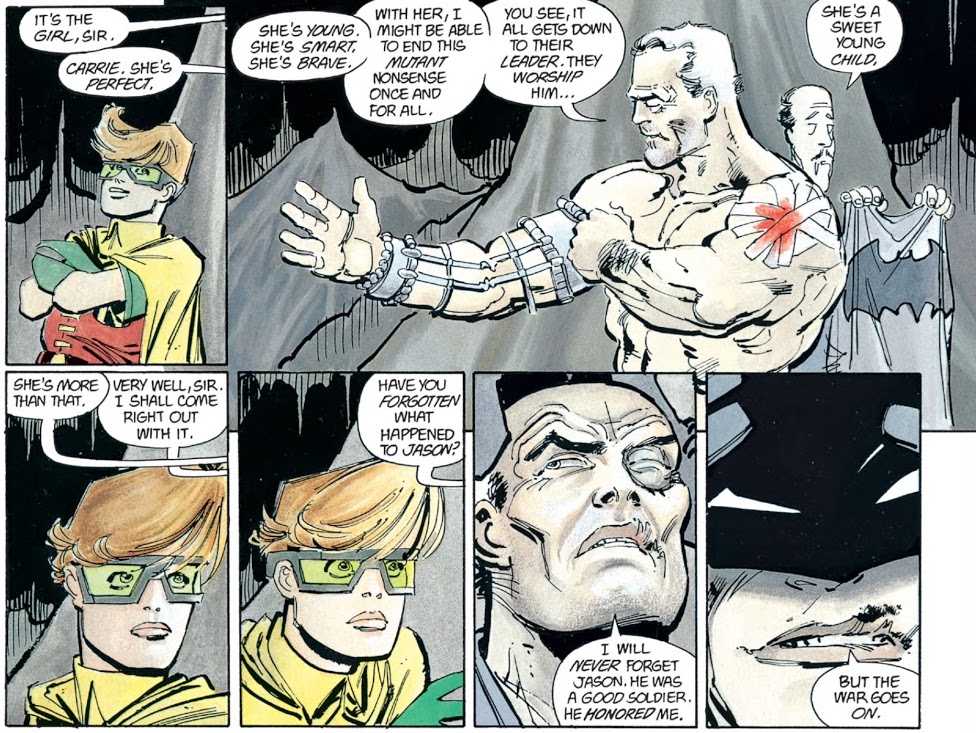

Miller: The thing they did right was, they gave Jason a massive inferiority complex. He really had to measure up to the previous Robin. That, I think, was very refreshing at the time. I wanted to break that when I brought Carrie [Kelley] in, by making her completely fearless, and not worried at all about measuring up to anything.18

Conway: In one sense [Jason’s death] did allow for the entrance of the real ‘Dark Knight’, the idea of Batman as the pitiless enforcer of Gotham. It did have a long-lasting emotional effect on the stories, but I think it was primarily a product of a cynical sales grab.19

Miller: “A Death in the Family” should be singled out as the most cynical thing that particular publisher has ever done. An actual toll-free number where fans can call in to put the axe to a little boy’s head. To me the whole killing of Robin thing was probably the ugliest thing I’ve seen in comics, and the most cynical.20

Raspler: I don’t have any clear memory of [reaction to Jason’s death], other than people making fun of the cynicism of the project, and friends mocking me for being associated with it. To this day I get some of it. You can’t bring it up because it’s, ‘Of course, Dan killed Robin.’8

Starlin: [Jason’s death] worked out well on sales, not so well for me, though. They suddenly realized after they killed him off they had all these lunchboxes and pajamas with Robin’s pictures on it, so within six months I was out at DC. Things sort of dried up. It was okay, I went back over to Marvel and I did The Infinity Gauntlet, so it worked out okay.15

Raspler: If I really attempt to commune with my former self, I might be able dredge up memories of Denny saying something like, “well, I would love to update that corny kid costume, but I bet both marketing or licensing would complain, so we’re stuck with short pants and elf boots.”8

Grant: I knew that we’d need a new Robin at some point—no comics company ever leaves a hero dead for long. When Norm and I created the character of Anarky I had high hopes that he might become the new Robin. But unknown to me—to any of the Bat-crew—Denny and Marv Wolfman were already working on Robin’s replacement and had created Tim Drake.11

Conway: I was more interested in [Jason] after he was killed off and when he was brought back as various reinterpretations of the character. That seemed, to me, more interesting, because honestly he was, at least before he was killed, not that well-developed a character. Much like Gwen Stacy, he’s someone who is more interesting in death than he was as a character in his original state. And I think that’s valuable, so that works for the character. If he had just continued as a sidekick I don’t think he’d be very interesting. It’s always fascinating to me how characters are reinterpreted and re-evaluated. I’m always interested in what new takes people have on the characters that I created. I don’t feel any personal ownership in them, but it’s sort of like watching your kids grow up and go off in different directions. It’s kind of cool.1

O’Neil: The death of Robin caper also made me realize that all this goes a lot deeper in people’s consciousness than I thought. All these years, I’ve considered myself to just be writing stories. I now know that that’s wrong. That Batman and Robin are part of our folklore. Even though only a tiny fraction of the population reads the comics, everybody knows about them the way everybody knows about Paul Bunyan, Abe Lincoln, etc. Batman and Robin are the postindustrial equivalent of folk figures. They are much deeper in our collective psyches than I had thought.4 Superman and Batman have been in continuous publication for over half a century, and that’s never been true of any fictional construct before. These characters have a lot more weight than the hero of a popular sitcom that lasts maybe four years. They have become postindustrial folklore, and part of this job is to be the custodian of folk figures. Everybody on Earth knows Batman and Robin.21

Many thanks to those who granted new interviews for this project, and to Maggie Thompson and Karen Green for research assistance.

Bibliography

1 Conway, Gerry. Skype interview. 4 October 2018.

2 Wolfman, Marv. Behind the Mask: MARV WOLFMAN on the Creation of NIGHTWING. Interview by Dan Greenfield. 13thdimension.com, 13 May 2018. https://13thdimension.com/behind-the-mask-marv-wolfman-on-the-creation-of-nightwing/

3 Perez, George. “Power and Subtlety: the George Perez Interview.” Interview by Michael F. Hopkins. Amazing Heroes, 1 July 1984: 40-53. Print.

4 O’Neil, Dennis. “Notes from the Batcave: An Interview with Dennis O’Neil.” Interview by Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio. The Many Lives of The Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media, edited by Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio. London: BFI Publishing, 1991, pp 18-32.

5 Collins, Max Allan. Interview via email. 14 October 2018.

6 Barr, Michael W. “Mike W. Barr on Batman: The Comics Alliance Interview, Part One.” Interview by Chris Sims. comicsalliance.com. 18 September 2013. http://comicsalliance.com/mike-w-barr-on-batman-the-comicsalliance-interview-part-one/

7 Collins, Max Allan. Watching the Detectives: An Interview with Max Allan Collins. Interview by Kim Thompson. Amazing Heroes, 15 June 1987: 23-41. Print.

8 Raspler, Dan. Phone interview. 27 September 2018.

9 “Robin: The Hero’s Journey.” Terrificon 2018 panel discussion. Panelists: Dennis O’Neil, Jim Starlin, Mike W. Barr, Tim Seeley, Peter Tomasi. Moderated by John Siuntres. 19 August 2018. http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wordballoon/2018/09/29/comic-books-robin-and-the-men-who-created-him

10 Starlin, Jim. “A Chat with Jim Starlin.” Interview by Shaun Clancy. Back Issue. May 2011: 21-46. Print.

11 Grant, Alan. Interview via email. 30 September 2018.

12 McGloin, Matt. Idea to Kill Robin Came From AIDS Epidemic, Says Jim Starlin. Cosmicbooknews.com, 26 October 2016. https://www.cosmicbooknews.com/content/idea-kill-robin-came-aids-epidemic-says-jim-starlin

13 Franklin, Chris. “Dead on Demand: Jason Todd, the Second Robin.” Back Issue. May 2011: 67-76. Print.

14 O’Neil, Dennis. Denny O’Neil: Getting Rid of Robin — Twice. Interview by Dan Greenfield. 13thdimension.com, 20 December 2014. https://13thdimension.com/denny-oneil-getting-rid-of-robin-twice/

15 Starlin, Jim. Behind the Panel: Jim Starlin. Interview by Mike Avila. syfy.com, 27 February 2018. https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/watch-jim-starlin-behind-the-panel

16 Kahn, Jenette. Interview via email. 24 September 2018.

17 “How, why, and when Robin died: A year to the life or death of Robin, or How Jason’s fate was decided in more than 365 days.” Comics Buyer’s Guide #789. 30 December 1988: Cover, 3. Print.

18 Miller, Frank. “INTERVIEW: Miller & Romita Reunite for New “Dark Knight Returns” Story.” Interview by Albert Ching. cbr.com. 15 June 2016. https://www.cbr.com/interview-miller-romita-reunite-for-new-dark-knight-returns-story/

19 Conway, Gerry. “Episode 38: Jason Todd with Gerry Conway Interview.” Interview by Kevin Volo. Audio blog post. Heroes, Villains, and Sidekicks Show. 18 June 2017. Web. http://heroesvillainsandsidekicks.com/episode-37-jason-todd-gerry-conway-onterview/

20 Miller, Frank. “Batman and the Twlight of the Idols: An Interview with Frank Miller.” Interview by Christopher Sharrett. The Many Lives of The Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media, edited by Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio. London: BFI Publishing, 1991, pp 33-46.

21 Daniels, Les. DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes. New York: Bullfinch – Little, Brown, & Co, 1995, pp 200-201.

This was great. I was 17 years old when the vote came out and was fascinated with the vote. love hearing from all the people involved with the creation and destruction of Jason Todd

Great article!

Do Tim Drake next!

Very thorough and with great contributions by the people who were involved from beginning to end. THIS is great writing!

Kudos!!

Wonderful look back at unique moment.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful article! Great stuff!

That was a good read.

This feature was great. I think you guys should do more of these.

Interestingly, Starlin slightly sanitized his comments here in comparison to what he’s said elsewhere about the character they were mulling about contracting the AIDS virus. He previously claimed Jimmy Olsen got the most votes by a wide margin, but that actor McClure who played him in the films was Gay, so they avoided it.

Some years ago I read an interview with Jim Starlin in which he casually mentioned that Robin was always going to die and that the reader call-in was all a publicity stunt. He says nothing like that here but neither does he retract what he said in that interview years ago.

Awesome read!

First rate job!

Comments are closed.