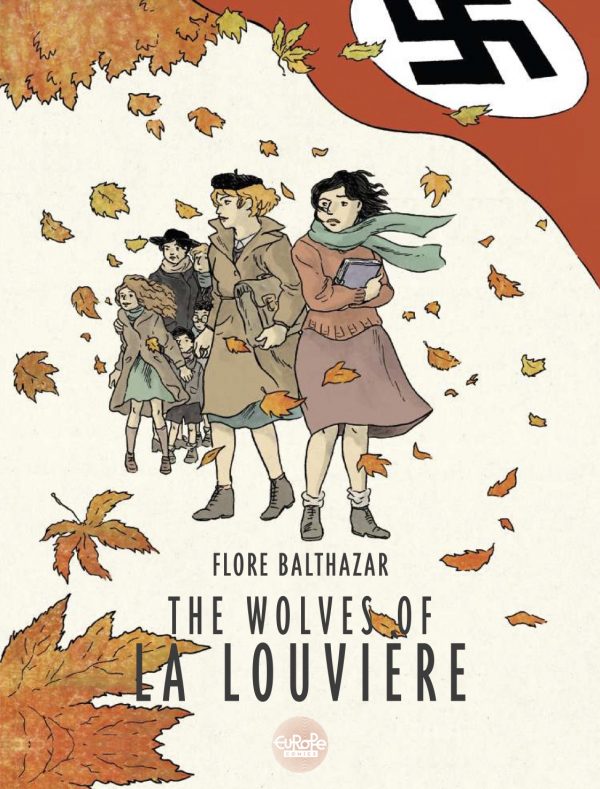

Europe Comics has carved out an interesting niche by releasing French and Belgian comics in ebook format to make them more available and affordable, and The Wolves of La Louviere is one of the companies finest achievements. Written and drawn by Belgian cartoonist Flore Balthazar, The Wolves of La Louviere mixes history and fictionalized biography with snippets of fairy tale narrative like something out of the Grimm Brothers adding a mythical context to the very specific events of World War II, as well as formalizing the book’s hybrid existence of fact and fiction coexisting.

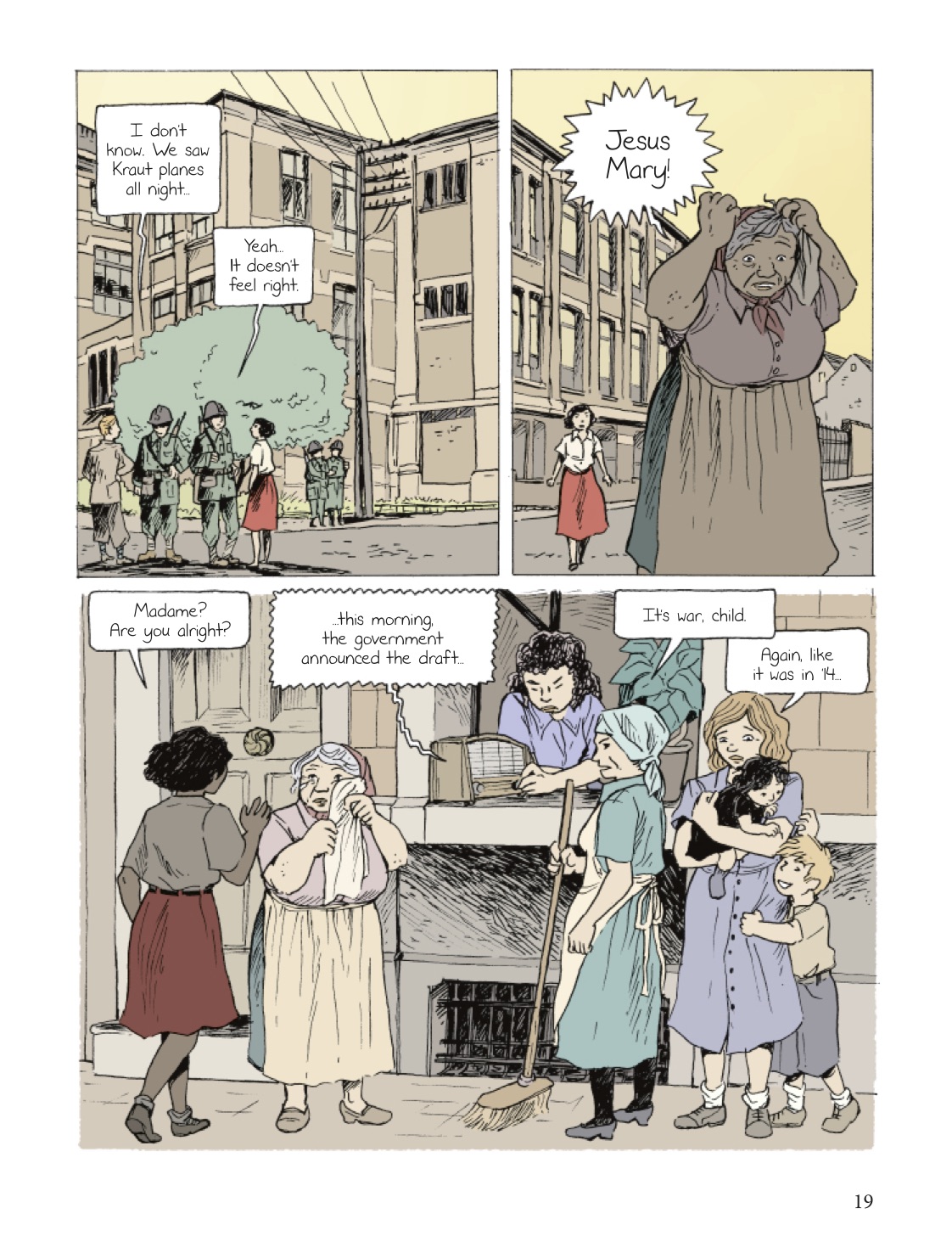

Portraying lives from 1940 to 1944, and then beyond, in a Belgian village, Balthazar captures the slow pace of the situation well. We often think of Europe at the time as all battlefronts, but it was also a collection of occupied rural lands where residents were expected to continue living their lives in some respect despite a Nazi presence in their lives. Balthazar does well to examine how people approach this problem and she does it in realistic, sympathetic terms since it’s very easy to judge when you’re looking so far backward.

The story mainly concerns itself with Marcelle Balthazar, the oldest daughter in a family with five children. Marcelle is completing school and preparing for college. Intelligent and hoping for something more out of life, the war and occupation cause her general distress and worry, but she works to keep it from obstructing her from the goals that existed before the war and if she survives it, will exist afterward.

Marcelle has a keen eye for what is going on around her, and she sees the ease with which some residents collaborate, while at the same time recognizes the Nazis as humans that she has to maintain enmity toward even as she looks at the reality of their existence. In this way, Balthazar captures the situation with a compassionate eye and seems to be asking directly what any reader would do in the same situation. Do you outwardly battle the enemy? Do you acquiesce? Do you embrace the enemy? Or do you finagle some form of subversion that can go undetected?

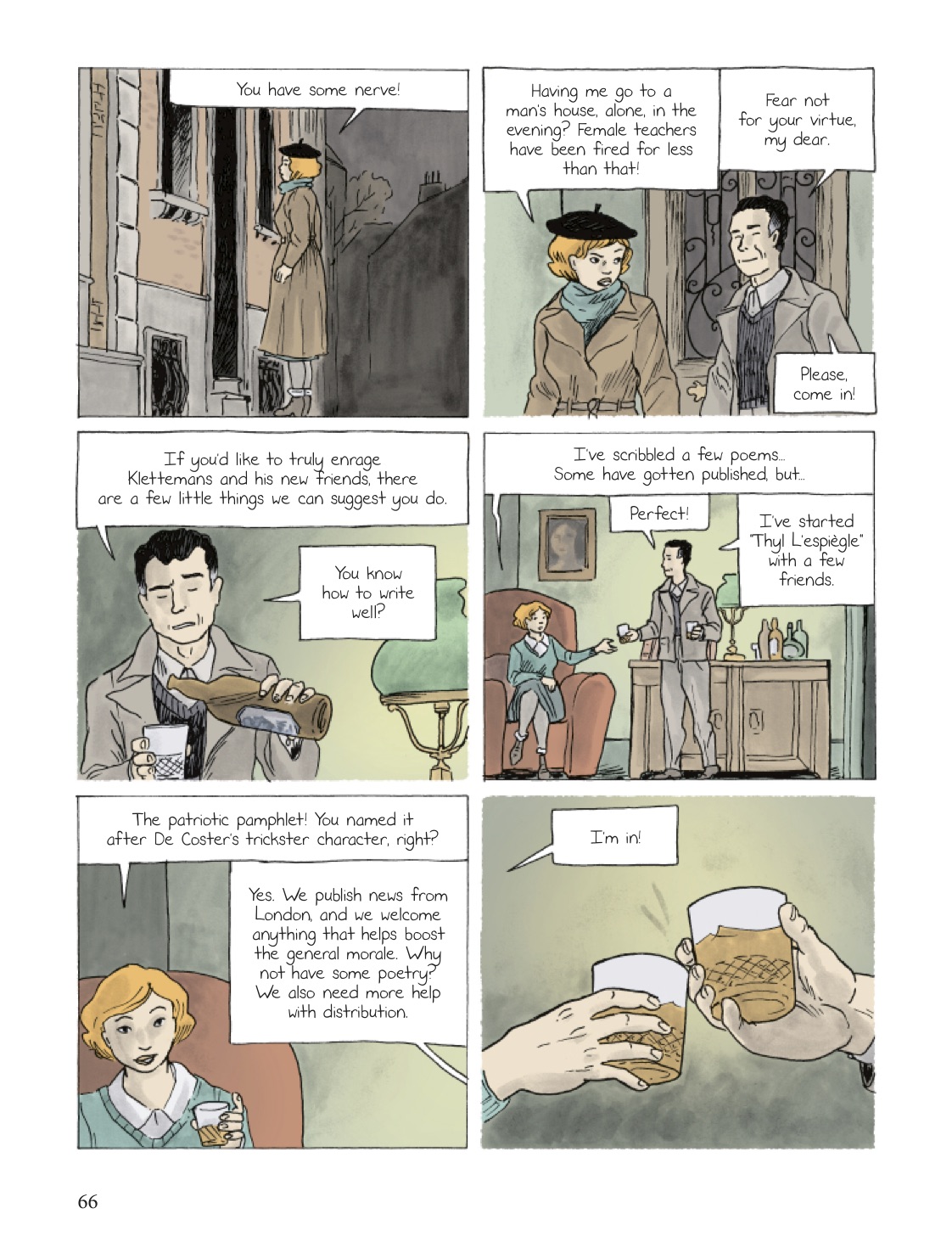

That last strategy is the one local school teacher, Marguerite Caluwaerts, opts for. To her students and in public, she cautions against agitating against the Nazis and even advocates treating them well. Behind the scenes, she is passing information as part of a resistance movement and helping combatants trapped behind enemy lines escape possible captivity. That character is based on an actual Belgian woman named Marguerite Bervoets, a member of the Belgian resistance group Five Bells, who was eventually captured and executed by the Germans.

Balthazar juxtaposes these two women’s stories as different ways of getting through the conflict and places no judgment on either. The Balthazar family itself seems to be directly based on the creator’s actual ancestors, and Marcelle seems to be the creator’s grandmother — I’ll admit that I’m guessing about that since I haven’t noticed any confirmation — and the book is built around her diaries.

Balthazar’s art style is that classic form of French/Belgian comics style that evokes Herge and creates a reality that exudes a kind of nostalgia and charm, with some soft realism, typically aimed at kids. It’s a style that works incredibly well for the subject matter, nestling the events depicted well within the time they took place and portraying the slowness of those events. The true jolts of the experience don’t come until the end of the war, and Balthazar portrays that very well, with the characters and settings that were previously charming being forced to face up the destruction of the predicament that they had previously only encountered one tiny aspect of.

The book finishes with a historical essay by a Belgian historian that covers the facts behind Balthazar’s presentation, with plenty of excellent photos of the Balthazar family, Marguerite Bervoets, and their village. It also shows that the dilemmas faced by the characters in the book — decisions about what kind of lives they were going to live in such dark times — were real dilemmas that any of us can and do face, and it speaks to the idea that we may never know what our actions mean in the context of history until its too late.

Cool.

Hey John, as someone who are not particular interested in superheroes your reviews are appreciated. I’ve bought quite a few books based on your recommendations, and this one goes straight on my Comixology wish list.

Thanks, Max! I really appreciate your comment!!

Comments are closed.