What is it like to be of the most despised nationality in modern history? I’m not talking about being an American, though it’s not outrageous to think our history of slavery and treatment of Native Americans would qualify us for that dubious honor. It’s Germany that is so reviled in history, maybe deservedly, maybe not, but almost certainly because if they didn’t perfect evil, at the very least they certainly perfected the popular visualization of what it looks like and those images stay in the minds of generations of people all around the world, equating the German Nazi with the ultimate manifestation of organized evil on the earth. It’s not an unreasonable worldview to have.

But when you get past the wide swathes of history and focus on the personal, you find the horrible truth — Nazis were human, living lives that involved other humans, most notably family and most significantly children, grandchildren, and further on, who live their lives long after the horrific reality of Nazi Germany has ceased to be the eternal present.

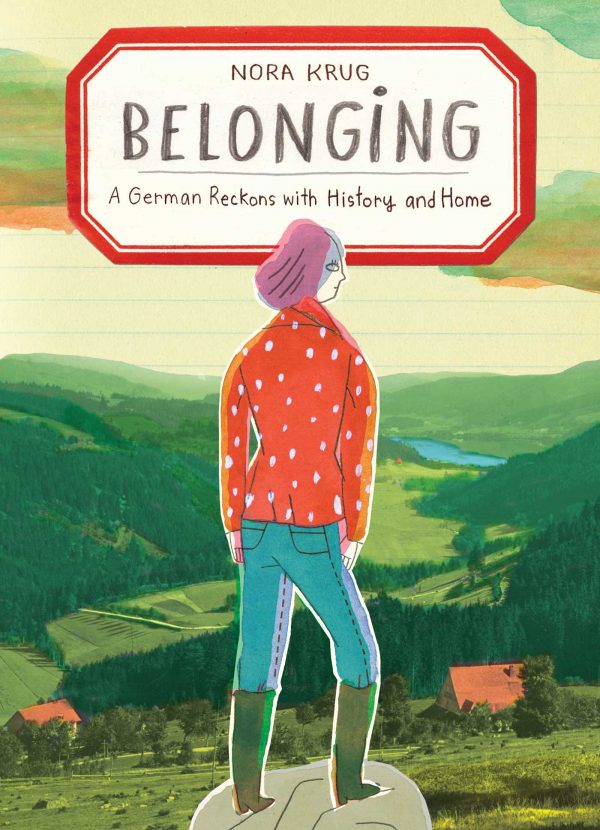

In her profound and dense illustrated memoir Belonging: A German Reckons With History And Home, illustrator Nora Krug examines her national identity and her family’s history to try to explain why Germans are the way they are by delving into the Hitler-era questions she has about her own family. What she finds is the story of the decisions everyday people make in the face of dark historical moments, of the fraught and painful revelations that lead us to judge the actions of our ancestors even as we move ahead in life, unaware whether our own actions will be judged in a similar way one day. In the face of horrible times, will we know what we should have done at the moment we should have done it? Or will we become lost in the confusing swirl of the present like so many before us?

Look at your life so far in regard to the wider political situation. Are you confident that your grandchild will find nothing to question your decisions?

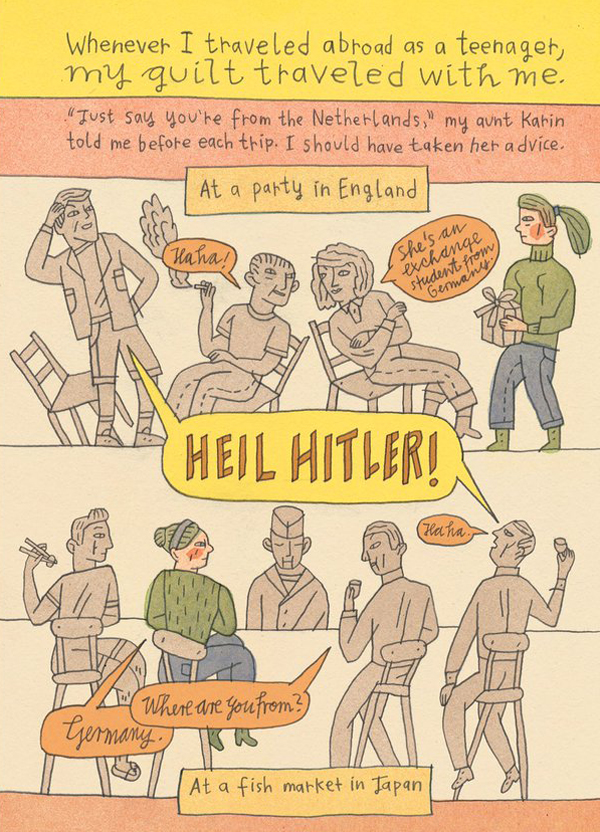

Krug’s look into her own life begins with an examination of German-ness in general, winding through cultural touchstones that are important to Germans, but also taking time to look at how her generation has been raised to comprehend World War II and the Holocaust, and how that generation’s philosophy of life is affected by that comprehension, as well as the reaction of non-Germans to German history. Part of this journey is spurred on by Krug living in America, partly removed from her German home, while another is a reaction against the broken quality of her extended family and the blackouts of family lore that have resulted.

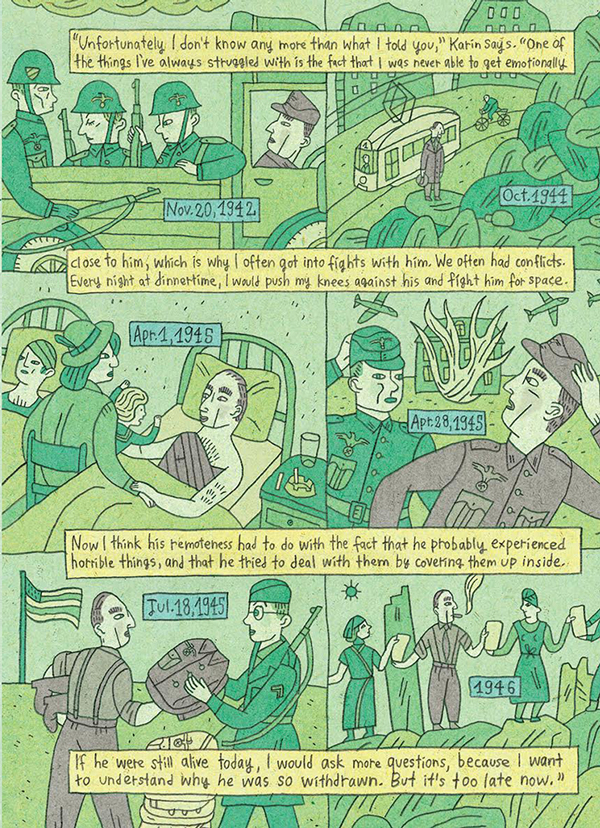

Krug’s curiosity begins to demand the answer to what many Germans of her generation must wonder — what did her grandparents do in the war? The families have their own beliefs about the grandparents, but Krug is fixated on getting to the truth, regardless of what relatives think is the truth. A good portion of this means researching the life of her mother’s father, Willi, and weighing the proof she finds of his concrete involvement with the Nazi Party against the more speculative personal story of why he was involved and what personal associations he had that might mitigate this circumstance.

For her father’s side of the family, it becomes a more complicated story in terms of family ties, with Krug’s father estranged from his own sister and the rest of the family, and the mysteries of a deceased older brother looming in the lore. Krug’s quest becomes much larger here, not only about reconciling her to her heritage but repairing rifts in her family that have obstructed the natural flow of biography.

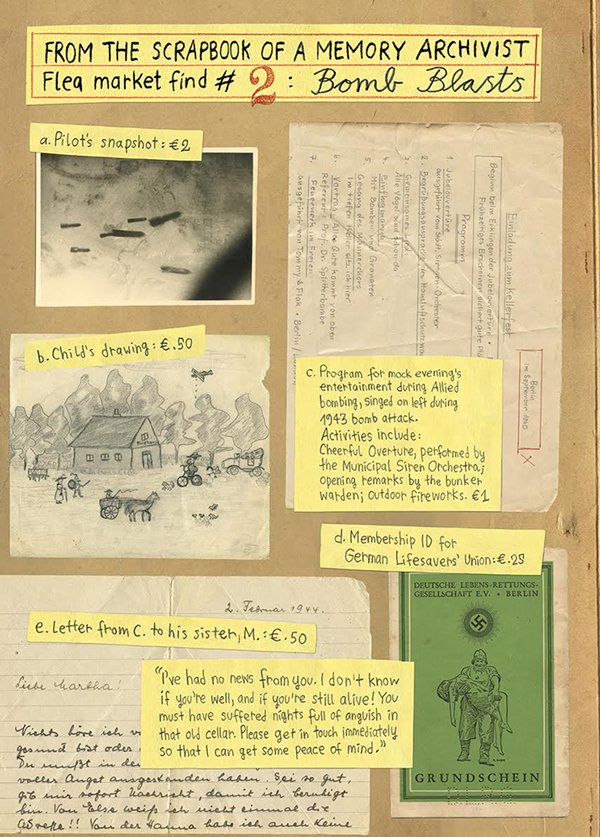

It’s to our benefit that Krug gives herself so fully to her research, and her ability to spin the facts around real emotion and insight concocts a history both personal and sweeping and thorough from each vantage point. The narrative jumps between illustrated prose describing her journey and comics-formatted informational sections that help visualize the society and the personalities and lives her work uncovers. Krug also incorporates photos and actual documents into the book, and that supplies a firm footprint in the real world that blends well with her artwork and handwriting.

Krug’s book is as valuable as it is personable, a reminder that humans are the ones living through history and that their lives seldom live up to the binary demands of our right or wrong way of thinking. Human life is more often a gray existence than one of stark values, and Krug is able to convey the breadth of the complications that make it so. It is not enough to say this person was a Nazi and capture the whole picture — a person is a creature of complexity that even one section of evil within them doesn’t necessarily dominate.

And so I consider Krug’s grandfather Willi as I think about the fervor in the 21st Century to define people by their worst aspects — say racism or sexism as two of the most common — and wonder despite the despicable parts whether we see the human or just the transgression. Is evil something we are or something we do? Can you be or do evil just by association, or is there more involved? And what are the consequences of defining evil in nationalistic terms? Is that not a myth that absolves everyone else’s evil?

I can only thank Krug for taking this project on — not just for putting herself and her family out there as fodder for the bigger questions, but actually asking the bigger questions as she goes through such a complicated, personal journey.

Comments are closed.