Johnny Appleseed is one of those American historical figures who calls into question the line that divides reality from fantasy. He seems like a myth, and certainly,the way he has been presented in the past is a fictionalized version of a real person, and this is the version that many Americans encounter. It’s one that plays into the all the other myths we have conjured that paint a benign picture of our society, which makes us feel better about the indiscretions of the past. But it also simplifies a complicated person, who existed for complicated reasons, energized by a complicated universal view, within a complicated country.

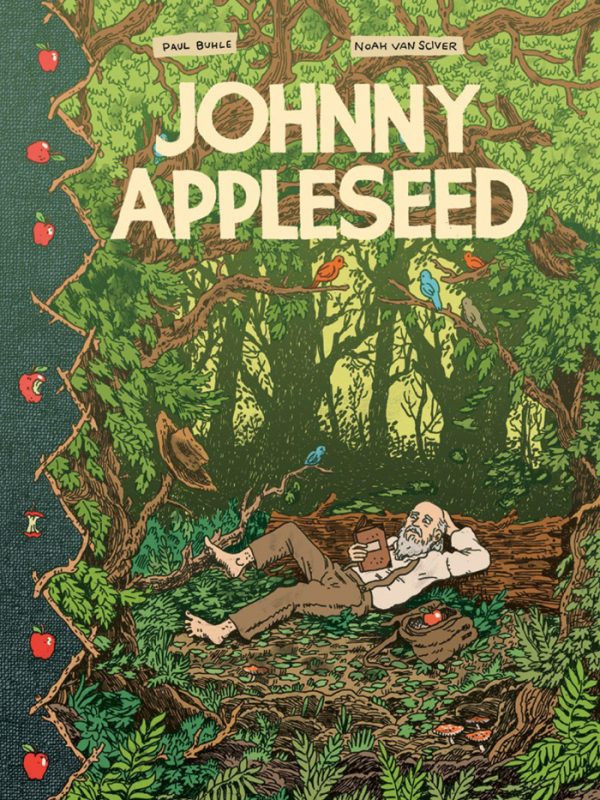

In Paul Buhle’s telling, Johnny Appleseed is a man with human concerns, but his existence is willfully transcendent in the same way as St. Francis, and the legends that have sprung up around the man function as an American version of Robin Hood. Not in the thievery-as-social-justice way, but in the human-as-nature-elemental way, in which a man communes so closely with the outdoors that he becomes a walking manifestation of it.

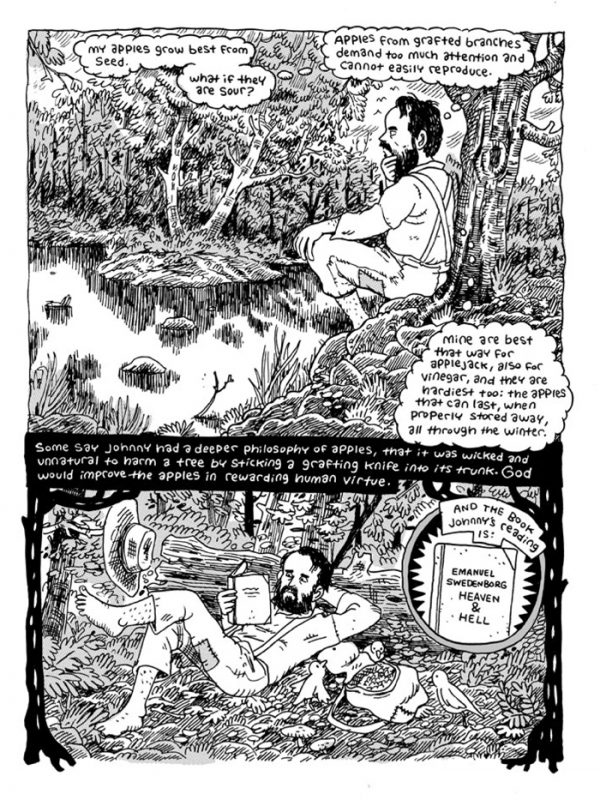

At one point, John the Baptist is evoked. Though it may be a stretch to directly lay various spiritual mania solely at Chapman’s feet, it’s still an apt point. That evocation is part of a sweeping detour from Chapman’s biography into, at first, the writings of Swedenborg, and then the wider Spiritualist movement in the country. Chapman was undeniably a non-conformist and radical, and the same thing can be said of the Spiritualists of the time. Chapman’s Swedenborgian beliefs were in direct line to these groups, which represented some form of sweeping change in American society, a rebellion from the Puritan stranglehold that traditionally reigned.

In offering this investigation of the wider radicalization in America at the time, a context is given to Chapman, regardless of his role in it, and it suggests that this era was a turning point for American society. Given the Civil War, a apocalyptic manifestation of the changes happening, and Buhle’s examination of the influence Chapman had on young Abraham Lincoln, it becomes more understandable how Johnny Appleseed can feel a little like John the Baptist.

Buhle also links Chapman to John Muir, partly in the realm of the natural, but especially with the idea of going on a journey to find oneself, generally considered one of the most American activities you can partake in. Certainly it’s easy to see the pieces of what would become the Appalachian Trail in this idea.

As Buhle points out, America has always been a nation of vagabonds moving where the work was, or never settling because of some better tomorrow that has been spied on the horizon or dreamt of in unvisited landscape. Finding your home, rather than remaining where you were born, has always been an aspect of American self-reliance. Buhle traces this idea from Chapman through the Depression onto the Beats.

And so this book becomes less a standard biography of a man — though it most certainly is in parts — and more a poem on the nature of America and the relationship between landscape and philosophy, with Johnny Appleseed as the manifested point of union between the intangible and the manifest.

It’s also a detour into spiritual expression beyond Chapman, giving good histories of Swedenborg and the Spiritualists and their relationship to good old American crackpotism. It’s a mad, mad, mad, mad country we live in, and everything swirling around in 2017 is all the same stuff finding new, and often upsetting, ways of expressing that.

In Buhle’s hands, with Noah Van Sciver’s rough rustic renderings of this 19th Century cross-section of reality and fantasy and the meaning of it all, history becomes more of a chaotic stew from which flavors must be isolated to be understood than anything orderly and right in front of you.

Comments are closed.