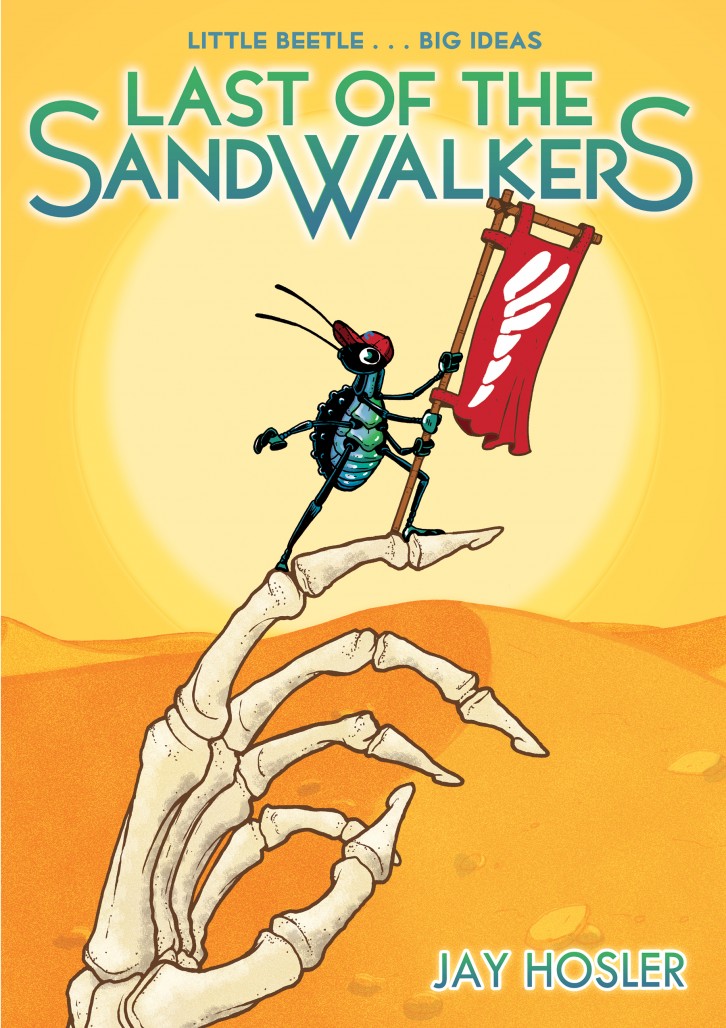

In Last of the Sandwalkers, Eisner nominee Jay Hosler combines his love of comics with his academic background in biological sciences and teaching. The result is a graphic novel aimed at students, ages 10-14, that has the intellectual weight to interest a much wider audience. Tackling themes like creationism vs. evolution, space exploration, and more, Last of the Sandwalkers features a pack of beetles searching for life beyond their home. With the graphic novel releasing today, we spoke with Hosler about the inspirations for the book and the utility of the graphic novel in the classroom.

What’s your “secret origin” in the comics industry? Have you always been interested in sequential art?

Like most kids, I was drawing at a very early age. The only difference between me and most of my peers wasn’t really the quality of the work so much as the fact that I never stopped drawing as I got older.

I have early memories of reading Tintin and Charlie Brown at my Grandmother’s lake cottage in northern Indiana. Grandma wasn’t a comics fan and I don’t think my mom or her siblings were either, but for some reason she had hardback volumes of Herge’s “The Secret of the Unicorn” and Schulz’s “Peanuts Treasury.” I would read and re-read those over and over.

I can remember being fascinated by the emanata each cartoonist used; squiggly lines and stars when someone got pegged in the head or sweat droplets flying into the air when they were nervous or tired. I started to reproduce those elements in my own drawings. Suddenly, all of the dinosaurs I was obsessively drawing were blushing, sweating and staring at stars circling their noggins.

It wasn’t until I was in second grade and got my hands on Marvel Team Up #19 that I started emulating sequential art. Stegron the Dinosaur Man drew me to the comic, but Spider-Man made me stick around for more. I started trying to tell stories with multiple pictures. These tended toward humor more than adventure stories and given my love of Peanuts most of what I tried to do was comic strips.

In high school, college and graduate school I did comic strips for the school newspapers. Unfortunately, they were pretty banal stuff; this class is hard, I can’t get a date, the bookstore charges to much, bad puns, etc. In the last 30 years, I’ve managed to shake all of those themes except bad puns. By the time I was in graduate school, I was doing a daily comic strip called Spelunker for the Notre Dame newspaper as well as a weekly strip called Cow-Boy for the Comic Buyers Guide. The problem is that I was really feeling the constraints of doing a four-panel strip and I wasn’t very good as a gag-man. I wanted to try something longer.

So, along with the editorial cartoonist at the Notre Dame newspaper and a fresh-faced aspiring writer named Bill Roseman (now of Marvel fame), I decided to give comics a try. We self-published a single, 22-page issue of Wired Comix. The comic contained three stories and was as well received as one could expect for something with such limited distribution. This whetted my appetite for more.

Eventually, I would make a 72-page issue of Cow-Boy that featured seven original comic stories. I loved it, but it was still primarily goofy humor and a super hero parody wasn’t really contributing anything new to the medium. Maybe it was the scientist in me, but I wanted to make a novel contribution to comics in the same way I was trying with my research to add a little something novel to our understanding of insect physiology. It was at this point that I made the leap addressed in the next question…

At what point did you decide to bridge the gap between your love and science and cartooning?

After I had gotten my doctorate, I stayed at Notre Dame for a year and taught a few classes. After getting your degree, the next phase of a scientist’s career usually entails postdoctoral work in another lab, so I was casting about for possibilities. I managed to land a position at the Rothenbuhler Honey Bee Research Laboratory at Ohio State University (sadly, no longer there, but not because I broke it).

My graduate research had focused on how insect muscle function was affected by low temperatures, but the work at Rothenbuhler would focus on how regions of the bee brain processed floral odors. To prepare for this work, I decided I needed to bone up on my knowledge of honey bee biology, behavior and natural history. Mark Winston’s book “The Biology of the Honeybee” was a revelation. Not only was it comprehensive and interesting, but it inspired me. I remember thinking, “Someone should do a comic about bees!” It wasn’t until I was a year into my postdoc that the little light bulb went off over my head and I realized that that someone could be me.

I wrote and drew the first issue of Clan Apis and submitted it for a Xeric Grant. Several weeks later, I got the news that it would be funded. In fact, I received that news in the same week that I received funding for a three-year grant form the National Institutes of Mental Health to fund my research and my salary. I think I was more excited about the Xeric.

You’ve crafted a number of graphic novels under your own publishing house (Active Synapse). What made you want to go that route from the outset? Did you find self-publishing came with its own challenges?

The decision to self-publish was ultimately made for me. No one was interested in publishing a biologically accurate comic book about bees in the late 1990s. I suppose if I had drawn them as buxom, gun-toting cyber bees I might have had a chance, but that wasn’t the route I wanted to go. Plus, I wanted the freedom to do the books the way I wanted. I used the Xeric Grant to get things started and then was lucky to form a partnership with my friend Daryn Guarino to form Active Synapse. This was great for my books and Daryn is an indefatigable business and distribution force. He is also a very talented man and has started writing his own books.

Self-publishing is difficult, expensive and it can consume your life and I think both of us wanted to channel our creative energies elsewhere.

How did the creative process for Last of the Sandwalkers compare to your previous offerings? Did you find that there were lessons learned that you could apply?

One of the big differences was the amount of ongoing feedback that I sought. I showed the first few chapters to a friend and his kids. These are bright, book loving kids and they weren’t sure what the heck was going on at the start of the book so their feedback stimulated me to add the short first chapter as a means of clarification.

When I had it half done, I passed the book around to a few cartoonists and comics loving friends to see if what I was doing was working. All of their feedback, along with my own glacially slow deliberations, helped me make the story better. Ten plus years is a long time to work on something without feedback. Thankfully I got some excellent advice and the book didn’t wind up a hot mess (IMHO).

I think the toughest thing for me was the fact that it wasn’t a strictly linear story like my past books. There were all of the hints of past event and flashback that I wanted to tie together with the present, but I wanted them to unfold like a mystery. This required mapping out the story, drawing connections, decided how much I could say and when I could say it. What was too subtle? What was too obvious? And how do I do all of this and make it appealing to the broadest audience possible? How do you entertain comic savvy folks and comic newbies? Kids and adults?

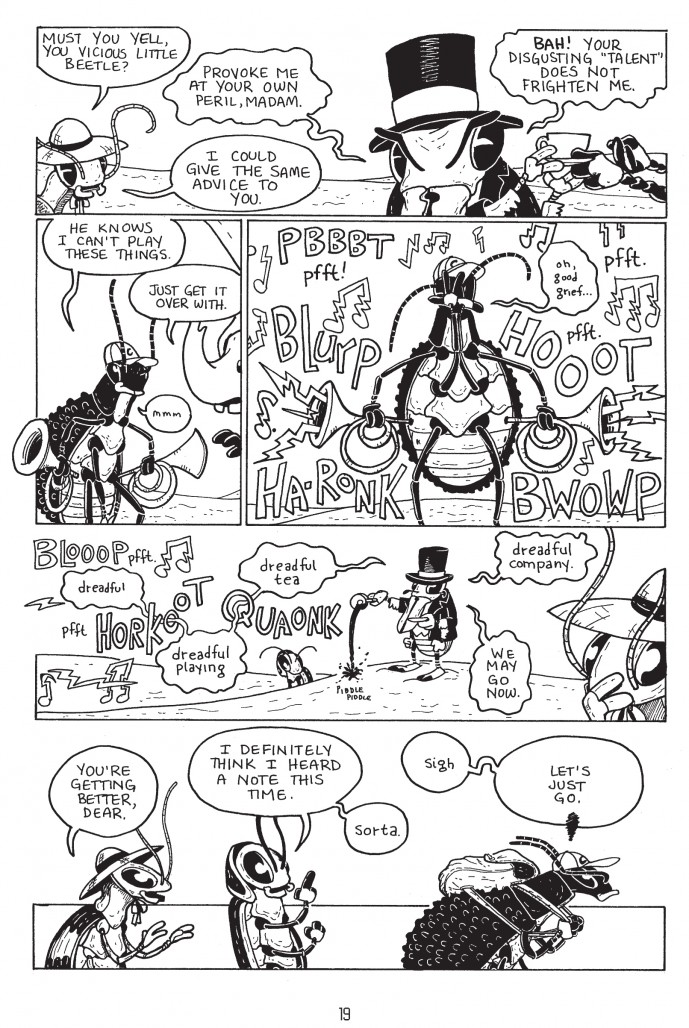

In terms of tone, my approach was the same with all of my other books. I emulated Looney Tunes cartoons. A Bugs Bunny cartoon had slapstick for me as a kid and word play and political commentary for my Dad. There was enough there to keep us both entertained and provide us with a shared experience. That is how I hope people respond to this book.

Did you feel as though you had a specific mission statement while working on Last of the Sandwalkers?

The science writer Matthew Ridly wrote a cover blurb for Richard Dawkin’s book The Greatest Show on Earth in which he praises Dawkins as a master of “wonderstanding.” I’m usually not a fan of cutesy words but this one has been a useful touchstone for me.

I want people to feel the sense of wonder I feel in the natural world. My goal is to share that excitement and to help provide them with more than just a surface appreciation. I want them to develop an understanding of how things works and how living things are interconnected and I want to have fun doing it. I also want them to forge an emotional connection with the natural world. Laughing and crying connects us to stories and the world in powerful ways. We come back to things that make feel. And if I can cultivate a sense of wonderstanding in my readers, then insects will become more than creepy crawling things we squish without a second thought. They will enrich our sense of who we are and our connection to the natural world.

When you’re creating a work as long as Last of the Sandwalkers, what exactly is your day to day work process?

My process was fundamentally the same for this book. I found a topic that captured my interest and started doing research, cobbling together notes and story ideas. I would write a script for a chapter, read it out-loud, edit, read it to my family, edit, start thumbnailing pages, edit, start drawing, edit, show the pages to my family, edit. Lather, rinse, repeat for each page. There were some false starts. I drew a version of the first chapter in a completely different, hyper-simple style that didn’t work.

For most of this book, there was no reliable day-to-day process. I could go an entire semester without having a chance to work on it at all. But the minute the semester ended and finals were in, I could get back to it. On the first day after my final class I usually drew a page and triumphantly posted it to Facebook.

My goal was usually to get a chapter of two done over the summer, but there were times when even that wasn’t possible. Last of the Sandwalkers took the back seat when paying gigs would pop up. I couldn’t pass up the chance to work with Kevin Cannon and Zander Cannon on Evolution any more than I could miss the opportunity to illustrate entomologist-extraordinaire May Berenbaum’s book The Earwig’s Tale. So, the beetles got shuttled to the back burner at times, but they were always in my mind percolating.

Do you script first and then move on to to the illustration stage or is there another method you find works best?

The story comes first. I need to work out the balance of science and adventure so that it isn’t too insipid or too ponderously didactic. But, as I noted earlier, once the first draft is done, there is a very dynamic feedback loop between drawing and writing.

At what point did First Second become involved? How has working for a large publishing house impacted your work?

Working with First Second was a dream. Our relationship started when I met Gina Gagliano (marketing) at SPX several years ago. I can’t remember how we started talking, but I had a draft of the first half of the book at my table and after she looked through it she said, “We’d be interested in this.” I was very flattered (and a bit surprised), but at the time I was still planning to self-publish. Of course, being self-absorbed, I tucked that compliment away in my mental files for future review. When my self-publishing circumstances changed, I put together a pdf of the first 160 pages and sent it to Gina. I don’t have an agent, so this was probably a bit brassy, but fortunately I was too dumb to know any better.

My future editor Calista Brill got back to me very quickly with a proposal and we were rolling. Calista was incredibly supportive and patient and the book is better because of her. Likewise Colleen Venable (the designer at the time) was an inspiration. She worked so long and patiently with me on the cover and in the process taught me a lot about design. Her covers are great, so I just followed her lead and we arrived at a cover that is infinitely better than the one I initially proposed.

Now, I’m working with Gina to market the book. She is so on the ball, it’s tough for me to keep up sometimes! She has lined up so many opportunities for me to promote this book and I am deeply grateful.

At every step of the way I have been treated with respect, patience and creative freedom. They’ve taught me so much and new knowledge is the greatest gift you can give an academic. I feel really lucky to be working with them.

Can you explain the relationship between The Sandwalk Adventures and Last of the Sandwalkers?

It was accidental at some level. Or perhaps serendipitous, I’m not sure. For most of the time I was working on the Last of the Sandwalkers, I was using a very different title. Once the ball got rolling at First Second, we decided that my working title might not be the most effective way to go, so we went back and forth for a long time and finally settled on Last of the Sandwalkers.

In The Sandwalk Adventures, the sandwalk was the place on Darwin’s property in Downe where he would take a noon stroll and talk to the follicle mite in his left eyebrow. In the comic, the sandwalk is where they would have adventures (both imagined and real).

In Last of the Sandwalkers, the main character is a desert beetle, or sandwalker, named Lucy. And, as the title implies, she is the last of her kind as far as she knows. Calling Lucy a sandwalker was meant to be a shout out to the Darwin book, but it really inspired my editor Calista Brill and she eventually convinced me that this was the better title.

That said, there are some interesting parallels. Darwin walked a sandwalk, so he was a also sandwalker. Lucy is a scientist living in an island oasis that is surrounded by a sea of sand. She eventually leaves the island and makes discoveries that reshape our view of nature. Sounds to me a lot like Darwin leaving England on the voyage of the HMS Beagle. Clearly, something may have been at work in the back of my mind that I wasn’t even aware of.

Is it difficult to find the right balance between providing educational facts and creative storytelling?

It can be, although I don’t think of the science I weave in as “facts.” My hope is that they are knowledge of natural history that the characters need to advance the plot or tell a joke.

As far as my approach to this is concerned, imagine a sci-fi show where the characters need to reverse the polarity of the tachyon beam to generate a ripple in subspace gravity field so that they can collapse a rift in the space-time continuum. When I structure a story, I just replace all that made-up sci-fi exposition with real natural history exposition. When I can, I try to set the stories in the real world, just not the human real world. The trick is to be willing to look at a worm or an insect as a marvelous, mysterious thing. An alien underfoot. You have to see the everyday from a different perspective, but when you do it can be startling and breathtaking.

Teaching has taught me a lot about weaving storytelling and science together. For every lecture I give or lab I run, I need to see the story in what we are discussing. Throwing a slide on the screen that is packed with information is a universal guarantee of trigger the sleep response. Information in any field requires context and cohesion and these are the elements that stories provide. A worm isn’t just a worm, it is a necessity for aerating soil or the scourge of terrace rice farmers. It is a force of nature working completely out of our site, moving and transforming the ground beneath our feet.

These are the things I keep in mind as I write, but I can easily delude myself. After all, I can enjoy a good textbook as much as a novel and I know that makes me weird, so I read everything I write to my family. They’re the final arbiters of what works and what doesn’t. They will tell me when to dial back the science or give them more. They will tell me when things are too frenetic or confusing or when I need some more excitement or humor. If I can get it right for myself and for my family, then I’m usually pretty confident the story is in a good place. For a book this long and complicated, I also sent it to several colleagues and friends to get feedback as I worked.

What attracted you to do the graphic novel medium as a tool for teaching? Have you seen an increase in the use of graphic novels as an educational tool?

Our brains are wired to receive information as pictures. When I give public talks, I often throw up a slide with a block of text describing an item. The definition I use comes from the dictionary and after about thirty seconds of reading and processing a few people raise their hands to tell me what it describes. Many other are still working it out when I through up a picture of a cog and everyone in the room immediately gets it.

Our brains also appear to be wired for story. Work form cognitive scientists is starting to demonstrate the importance of storytelling for memory formation and contextualizing information. Stories scaffold ideas for us and help us hold onto to those ideas and use them effectively.

As McCloud points out in Understanding Comics, we know this intuitively because we give kids picture books. Recognition of the power of pictures doesn’t go away when kids get to college. I pick the textbooks I use based on the quality of the illustrations and figures. But, the storytelling component is all but gone. For me, comics sit between these two extremes and I believe comics are the most powerful of all three possibilities for engaging and entertaining students and casual readers.

Of course, the medium itself is just fun and the best learning happens when we are enjoying ourselves.

The protagonists in this story are battling views very similar to creationism. Do you feel creationism is still a threat to our educational system?

Absolutely. We live in a free country and people are allowed to believe what they want to believe. You want to believe that the world was created in seven days? That’s your right. But that’s a belief that has absolutely no scientific evidence to support it. Of course, that isn’t an issue for creationists, because faith in that belief does not require evidence. The problem comes when believers start demanding that their faith-based beliefs be taught as a alternative to theories that are grounded in over a century’s worth of scientific evidence from paleontology, developmental biology, geochemistry, physics, anatomy, physiology, behavior, etc.

A science class is for science. Unfortunately, having the freedom to believe what you choose and pursue your beliefs without persecution doesn’t appear to be enough for some folks. They feel compelled to try to change laws and influence school boards and teachers to make their religious beliefs a part of the science curriculum.

Proponents of creationism are constantly changing their tactics looking for ways into the classroom, so we need to be vigilant. Remember Intelligent Design? It was all the rage in the 1990s. Proponents promised they would have experimental proof that never came, but in the meantime they managed to get their philosophy into several classroom.

The even bigger problem is that creationists have written the playbook for science denial. Their tactics have been modified and deployed by everyone from those denying climate change to the anti-vaccination crowd.

Is it difficult to espouse a pro-science message without creating an anti-religion tone? Or is that the point?

Any pro-science message is going to be read by someone, somewhere as anti-religion. It is true that Lucy butts heads with a religious fundamentalist in Last of the Sandwalkers, but I’d like to believe the story is more generally about the conflict between science and the powerful individuals and organizations that oppose it. The majority of those that seek to discredit climate change scientists and their results do so for economic reasons, not because of religious objections.

As I read, I definitely got a space/sci-fi feel from the book, even though it all takes place in small corners of the Earth. Last of the Sandwalkers is about the pursuit of science and exploration – is any of it meant as a commentary on the low levels of government funding in NASA and space exploration?

You bet. The human race has become like a comfortable older couple. We don’t going anywhere anymore! We need to dream again about the worlds beyond our comfort zone. When we are at our best when we are exploring and seeking to understand the universe better. Plus, the work done to get ourselves into outer space invariable generates technologies that make life better for us that stay on Earth..

…And lastly, we have to ask, just for fun. Any interest in the upcoming Ant-Man film?

Absolutely! The current Ant-Man comic is a hoot and it has some well drawn ants. Plus, I did do my own short Ant-Man fan film…

Comments are closed.