From the time the Scarlet Witch first appeared in X-Men #4 (March 1964), her fictional adventures have been pretty complicated. Now a new, eventually billion-dollar incarnation of the character has debuted on the big screen in Avengers 2. But why did the Scarlet Witch get the nod for superstardom? What about her resonates with so many of us?

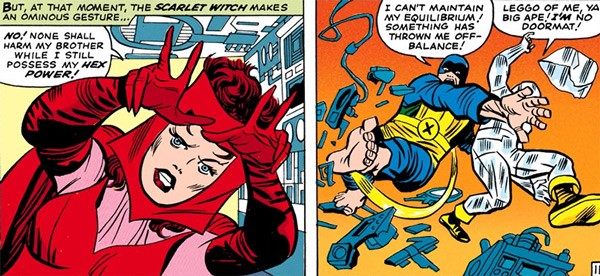

Wanda Maximoff, brother to Pietro (aka Quicksilver) and on-and-off-again daughter of Magneto, was the lone female member of the first Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. Alongside the gross Toad and even grosser Mastermind, she and Pietro played criminal only to pay off their debts to Magneto. They later joined the Avengers where (along with Hawkeye) they were referred to as “Cap’s Kooky Quartet,” which is thankfully way less catchier than “Age of Ultron.”

Even for the X-men, Wanda was a weird character. She was rescued by Magneto from Bearded Raised-Pitchfork Guys in a Generic Sorta-Real-Sounding Fictional European Country (Ending in –ania). This would later be (more or less) Nightcrawler’s origin, too.

Believe it or not, witchcraft was kind of a thing in the early sixties. And not the Wiccan-flavored Moon Crystal version we might guess it was. People were talking about real witches – “thriving,” no less:

These poorly-sourced, sensational headlines (made all the better by awful scanning) were probably just misplaced strains of anti-Communism. At the same time, there were stories out there of genuine human consequence. In this widely-reported, tragic story from 1962, an Italian man claimed that a former lover gave him the “Evil Eye.” He killed her with a sickle.

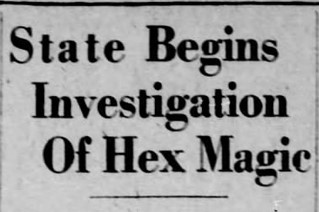

Though it sounds like a failed promotion for Honeycombs cereal, “hex power” was also part of the bundle of terms and clichés that were part of the contemporary witch:

Lee and Kirby’s use of the term “witch” also invokes a longer American history. In the wake of McCarthyism, the Salem witch trials of the late 1600s emerged as a great new metaphor for (Red) “witch hunting” of a different sort. Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible – of young women accused of witchcraft – enjoyed (unsurprisingly) a highly successful Broadway run in 1954. There were versions on local stages and on TV all the way into the sixties.

But the touchstone for Salem (and possibly for Wanda) will always be Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1850 novel The Scarlet Letter, which I bet you have a copy of the Cliff’s Notes for somewhere. We all read it in high school: Hester Prynne, accused of adultery, is forced to wear a red letter “A” in a romantic narrative of gender and religious high-mindedness. No spoilers, but Hester is also accused of consorting with a witch (a proto-Agatha Harkness). And the letter is, you know, SCARLET.

Not to turn this into high school English, but all that stuff in Hawthorne’s novel fits Wanda’s character, too. In her first appearance, she is portrayed as a very sexualized character.

Later on, she becomes more sexual than sexualized, but there are always restraints placed on her behavior by her partners. The Vision is a robot and Simon “Wonder Man” Williams is at times just a wavy bunch of static. Just like Dimmesdale’s priesthood limits Hester’s full expression of herself, so too do these Avengers. At the same time, Wanda (like Hester) is a character of great power whom everyone else fears. Both are capable of destroying entire communities, fictional and otherwise.

The 1926 film version of The Scarlet Letter starred screen siren Lillian Gish. Note her pilgrim headgear. It isn’t an exact match for Wanda’s own cut-out headdress (which looks like a costume for a 3rd-grade play about roses), but it’s getting there.

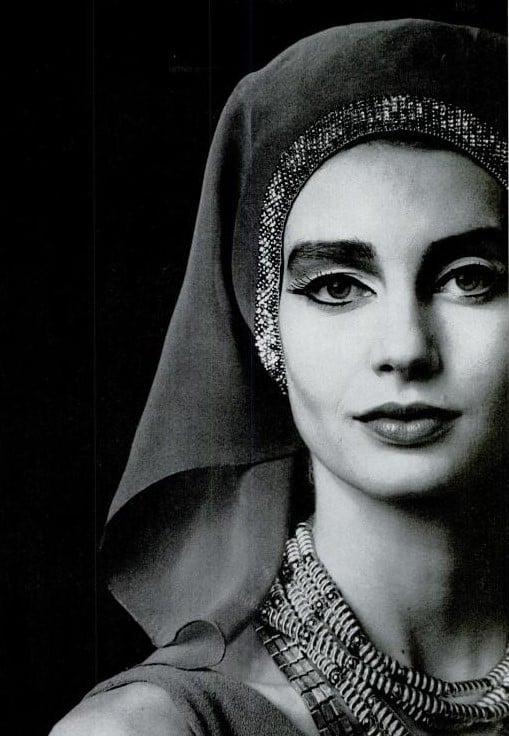

And until someone writes a dissertation about Jack Kirby’s obsession with massive, unwieldy headgear, I’ll go out on a limb and say that some of it must have come from Cleopatra, which released in 1963 and sported countless headdresses – and an astonishing 32 costume changes.

Liz and Dick’s little movie influenced fashion in the real world, including more headscarves.

Lycra and spandex were also in style,

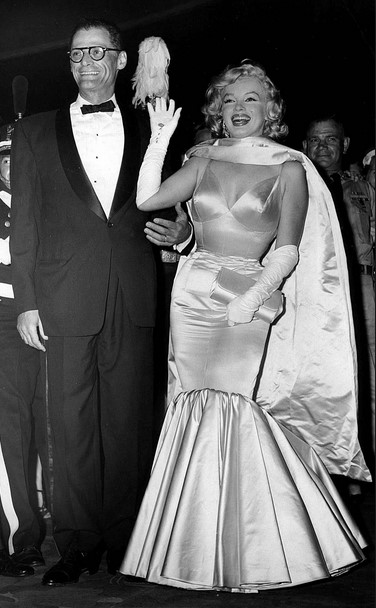

as well as the long gloves and open neck dress (with cloak) as seen here on Arthur Miller’s onetime wife, Marilyn Monroe.

Throughout Wanda’s long continuity, she has been treated as a victim, a hero, a villain, and a patsy at different times to different sets of eyes. She is complicated, which is maybe why she tends to be on the losing side of happy endings in her comics adventures. She loses husbands, parents, kids. Then again, it is her status as someone who doesn’t fit our ideals of the superhero that makes her just that more dangerous. Not only did Wanda get rid of 91.4% of mutants in the 2005 comics event “House of M.” But she also went back in time with Vision and Spidey to FIGHT THE REAL COTTON MATHER! That says something.

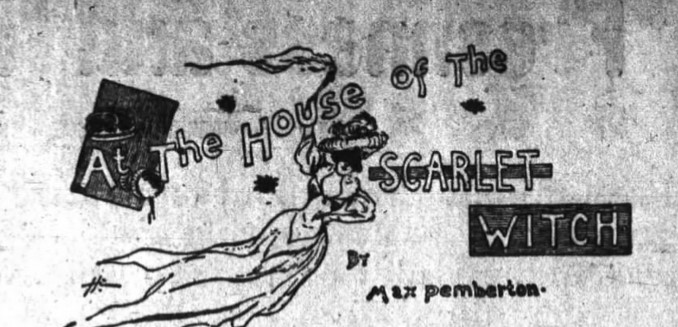

But there is more. It would seem even more improbable to say that another turn-of-the-century short story would have any influence on the Scarlet Witch. But since we are talking about seemingly impossible probabilities, here goes: this story by Max Pemberton features a central scene of a dinner feast hosted by a witch wearing red, with a strange, puffy hat:

At the table are strange people – some with horns, some dressed “like dwarfs” – enjoying a meal with goblets and candles. As they eat, they find that what they see is changing because it is all an illusion. Here is an illustration from the story:

This story, which was reprinted rather heavily (including the popular Pocket Magazine), has a very provocative, if highly improbable, title.

Brad Ricca is the author of the award-winning Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster – The Creators of Superman, now available in paperback. He also writes the column “Luminous Beings Are We” for StarWars.com. Visit www.brad-ricca.com and follow @BradJRicca.

Another brilliant piece of cultural detective work!

That excerpt you found of witchcraft interest in PA Dutch country really hit home for me – because that’s where I’m from. One of my goofy memories from being a little kid in the land of hex signs is coming back with my grandparents from Zern’s flea market, where I’d buy old comics and books, and my grandmother taking away the book I’d found revealing the secrets of witches. Ah well — power denied.

Great piece, not what I was expecting at all. Actual journalism! Loved it. It would only have been better if someone said “ho ho!” on page four of X-Men #4.

This is an amazing piece of reasearch/scholarship!

And I think you’re spot on about the Liz Cleopatra connection–I have long felt that Wanda’s look was inspired by that film, at least in part. Here’s an example I included in a blog post a few months ago:

http://twogirlsaguyandsomecomics.blogspot.com/2015/01/scarlet-witchs-hair-color-part-2.html

Fwiw, in terms of more X-Men connections in general, another of Pemberton’s works was titled “Doctor Xavier”‘ ;)

FWIW some fans have opined that Kirby swiped lots of his outfits from standard Shakespearean costuming.

I’ve long thought that Lee and Kirby based Wanda and Pietro on European folklore-elements, and Hawthorne as well.

Comments are closed.