Cartoonist: Masamune Shirow

Translation: Frederik Schodt and Toren Smith

Lettering: Tom Orzechowski and Susie Lee

Publisher: Dark Horse Comics

Publication Date: December 1995

As information eclipses all other forms, it’s natural to wonder if we’ll lose the ability to tell what’s real from what isn’t, or how real something even has to be. Who we are and what we are share a physical space, we have the technology to take away parts of the shell and replace them with artificial ones, we can rebuild you. Masamune Shirow’s manga, set in a time when so much of the human body can be substituted with other things that the only difference between robot and person is the source of their intelligence, is a foundational work of cyberpunk philosophy. It’s also lambasting it. To replace a part exactly is to build a cage that never allows your ghost to change. Ghost in the Shell is able to touch on something more than tits and tanks. It’s curiosity about ourselves, and we are a sum greater than its parts.

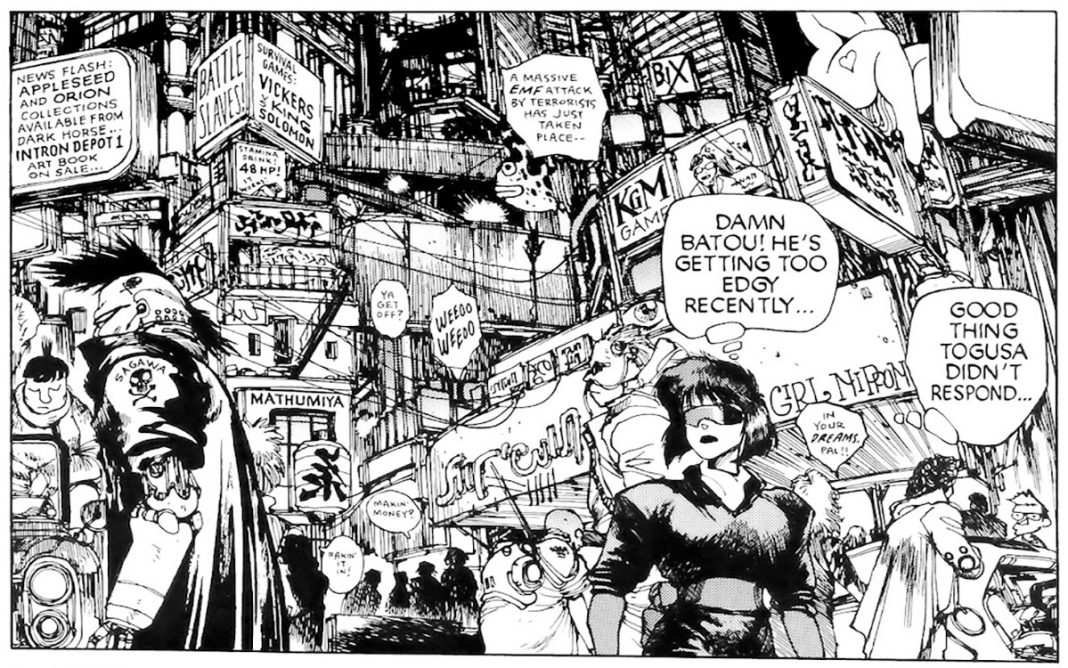

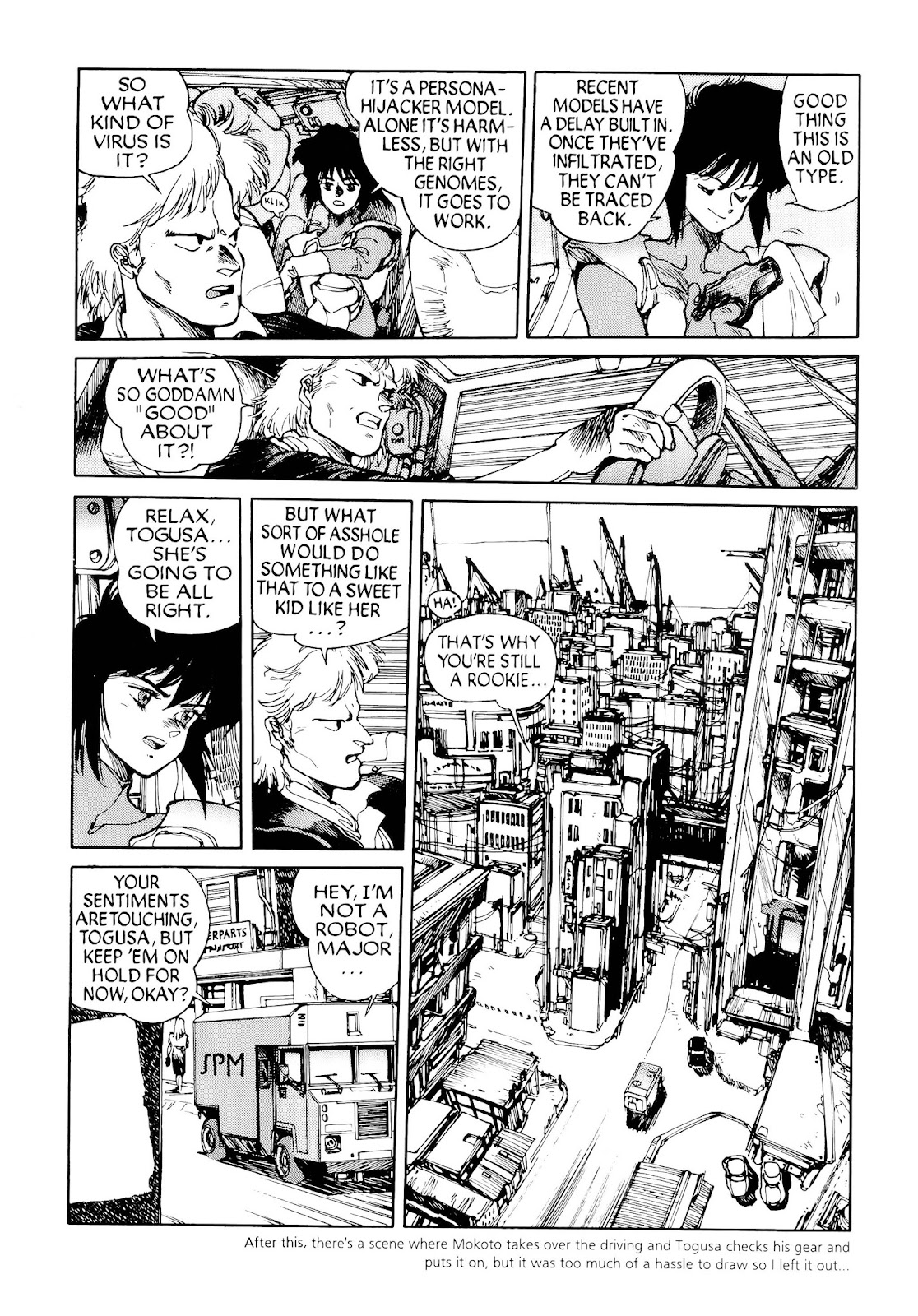

Ghost in the Shell, a stunning collision of depictions of technology, slapstick action comedy, and naked ladies, but what is it mostly? Reading. These police officers will absolutely drown you in words if they don’t shoot you to death first. Shirow’s comics are dense with philosophy and overarching ideas about artificial intelligence that drive the story, filled with constant witty banter between members of the secret police that’s endemic to the demagnetized moral compass of the future. A ton of this book is big blocks of text exploring hard science fiction concepts around body modification (set between diagrams, infographics, and other hard sci-fi visual aids). The answer to how much of a person you can take away and leave their humanity still intact is: your brain and your spine. You can’t just stick robot parts onto human bodies, if you flex your cyber-muscle without support you’ll yank out everything tied to its tendons. Better to replace the whole thing, better yet go full remote and use whatever body is convenient. What is real when everything you feel is through synthetic sensors? What’s the difference between synthetic and organic, what makes one superior?

There is a tremendous gulf- let’s call it satire- between what is being said with the characters and what is being said by the characters. The philosophy that is espoused in the dialog and not set into the story is mostly garbage. Intentionally? I think so? The kind of bullshit talk from cops that blames the victims. Useless big ideas that sound smart but intend to leave the world as it is. It’s iconic, really, an utterly deadpan pulp take. It doesn’t feel like satire because Ghost in the Shell is such a genre-defining work. The look of everything, the character design, technology ideas, the locations, guns and cars, the robots! The satire gets lost because the rendering of a cynical, twisted world is so good it is hard to discern if Shirow is buying their own hype. True love of the medium does not exclude being critical of it, the macho bullshit is as revered as it is speared. The line between satire and self-indulgence is nonexistent.

Shirow is an infamously horny artist, but Ghost in the Shell finds a way to put it to work. There’s posthumanism to the point where an executive is housed inside a black cube on little crab legs, yes, but you can bet his group of assistants/bodyguards are scantily clad and sweaty (literal) objects of the male gaze. The square-up is a con in writing that goes back as far as the arbiters of decency have interfered with art: I’m showing you these naked ladies to warn you about the dangerous things that happen to naked ladies. There is a cruel irony in there somewhere, the distance between thinking of people as property for sex and the act of intercourse’s relationship to the generative process and guardianship, and an artificial intelligence that manifests in a vessel for the former rather than the latter. That’s where the money is, the bleeding edge is sticky from other bodily fluids. It’s where the technology that is in stride with advances in artificial intelligence is being put to use: the indulgence of gross dudes. The hardware capable of containing a self-generated artificial intelligence isn’t a parent-bot or a nanny-bot, it’s a sex-bot.

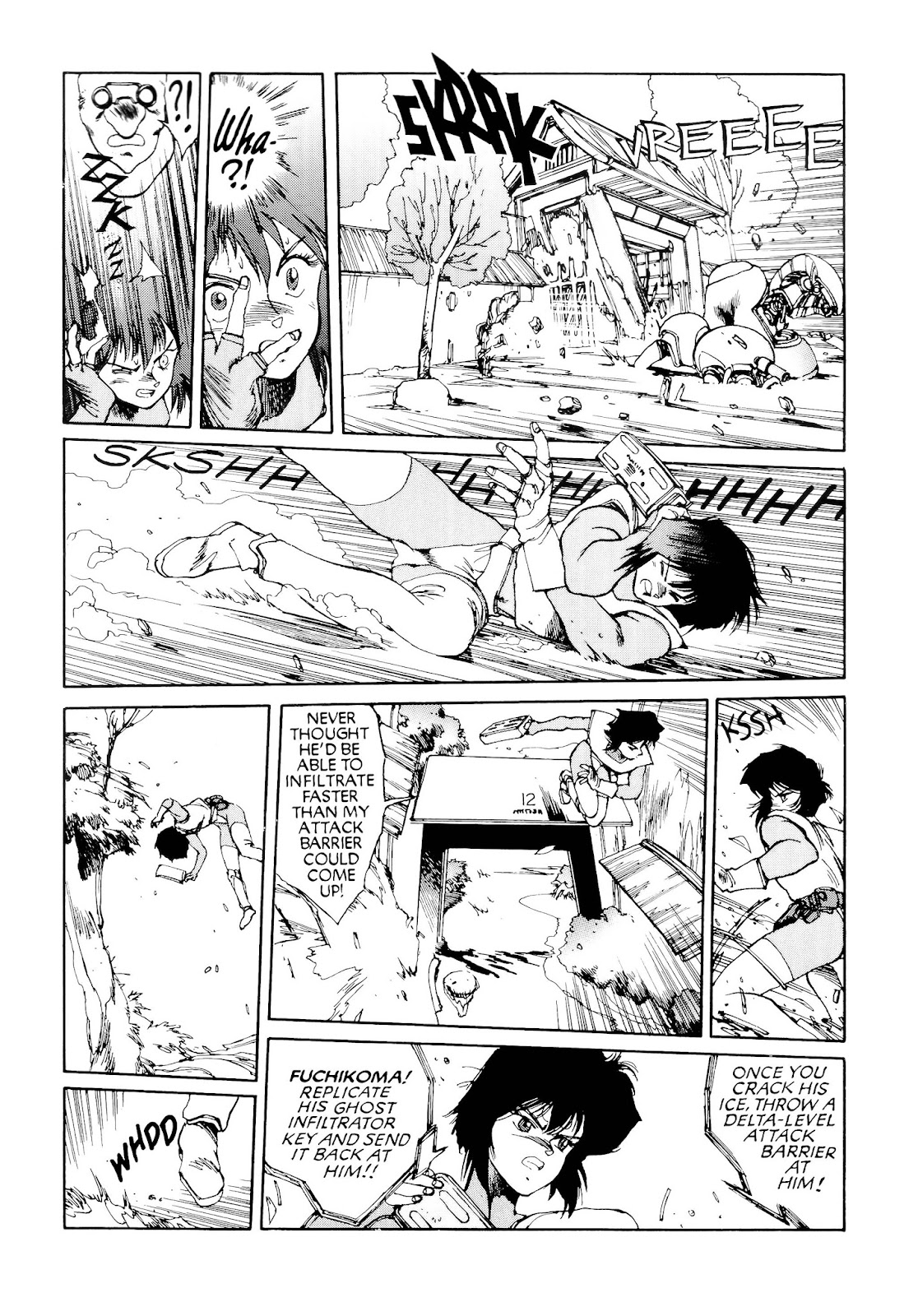

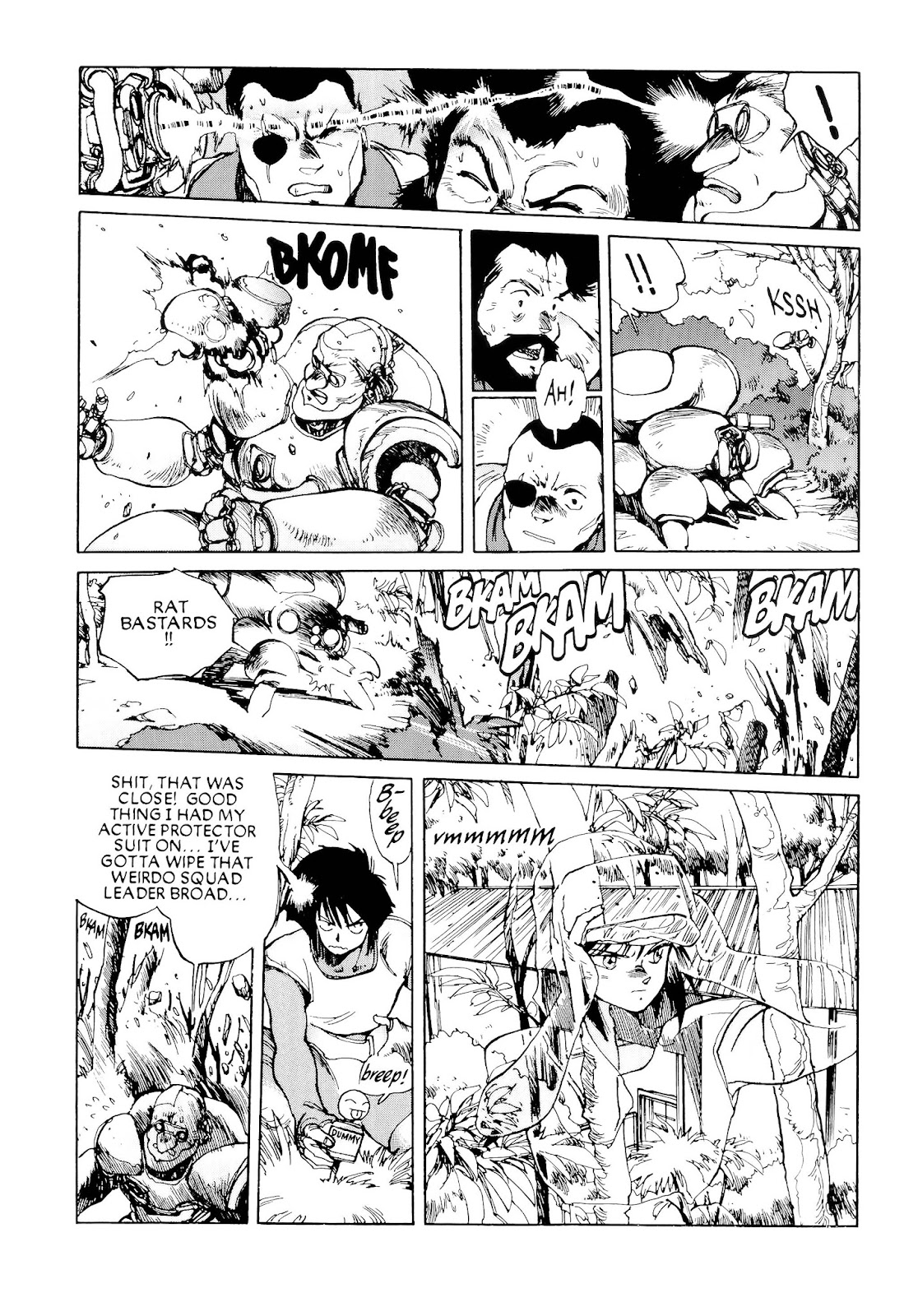

Masamune Shirow is cyberpunk. The art doesn’t conform to cyberpunk concepts, it is them. It is the law. Massive drops of fine detail, the overbuilt society is just that. Characters stand out against the page, but they’re still as heavily, heavily worked as the backgrounds. The story, the look, it isn’t going to defy your expectations- it will satisfy them, completely. Every single panel gets there. And while Shirow banks on visual capital, exquisitely rendered hard science fiction gives the hard boiled cliches grace. There’s a Police Story sensibility that the badass action never stands in the way of the silliness, slapstick, the adrenaline ecstasy that can give you giggle fits. Shirow knows how to lean into that, switching styles mid-panel from bishi beautiful boy to chibi super-head cartoon and it’s not whiplash you feel but the oomph of booster rockets kicking in. Buster Keaton shit. The goofy is so seamlessly integrated it doesn’t clash with the serious, it moves the boundaries out further than they were before.

Movement is what makes Ghost in the Shell an overlooked gem as well as a cult classic; Shirow is incredible at modulating the speed of the storytelling. This hits the reader two ways. The macho and the horny and the deep philosophy all give way at the drop of a hat to really powerful action that returns you to the forward motion of the book after consuming a mountain of exposition. Again the art is just perfect. The doing homework aspect disappears in the thrill of the moment. However, Shirow is also building the individual chapters on top of each other (to think thirty years ago Dark Horse was releasing chapters of Ghost in the Shell as individual issues you could pick up at radnom off the newsstand), setting the stage philosophically and contextually for what is to come at the end. That said, the order of things isn’t a chain of events one two three. It seems episodic, each standalone event a riff on the theme, but a web of connection lies beneath. The plot is a muscle car shifting between gears as it gains speed, slamming head first into the wall of the ending. It’s not an accident so much as placing the last puzzle piece. But the fun of a puzzle is putting it together, not finishing it, and Shirow gets that too: we’ve been watching Major Kusanagi drift away from being a super soldier the whole entire book. The ghost, the shell, well regardless of whether or not one replaces oneself with artificial pieces, time leave no one unchanged. Nobody is static. Everything grows. The net is vast…

Verdict: BUY

Read more trade collection reviews every Thursday in our Trade Rating column!