Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (or CXC) is a four day festival in Columbus, Ohio celebrating the work of cartoonists and providing chances to learn more about the medium. It’s mission is “to provide an international showcase for the best of cartoon art in all its forms, including comics, animation, editorial cartoons, newspaper strips, and beyond, in a city that is a growing center of importance to comics and cartooning. We also focus on helping the next generation of young cartooning talent develop thriving careers that invigorate the industry for years to come.” In the spirit of this mission, the Comics Beat has conducted a series of interviews with some of the phenomenal cartoonists in attendance at this year’s Cartoon Crossroads Columbus. We hope that these interviews will improve our understanding of these creators voices, techniques, interests and influences as well as provide a platform for comics enthusiasts to discover new artists and challenge their conceptions of comics.

This year, Cartoon Crossroads Columbus collaborated with SÕL-CON, The Brown and Black Comics Expo. SÕL-CON focuses on creators with a Latino or African-American background. It’s a different entity and convention than CXC, but they collaborated this year to make a more wholesome experience for attendees.

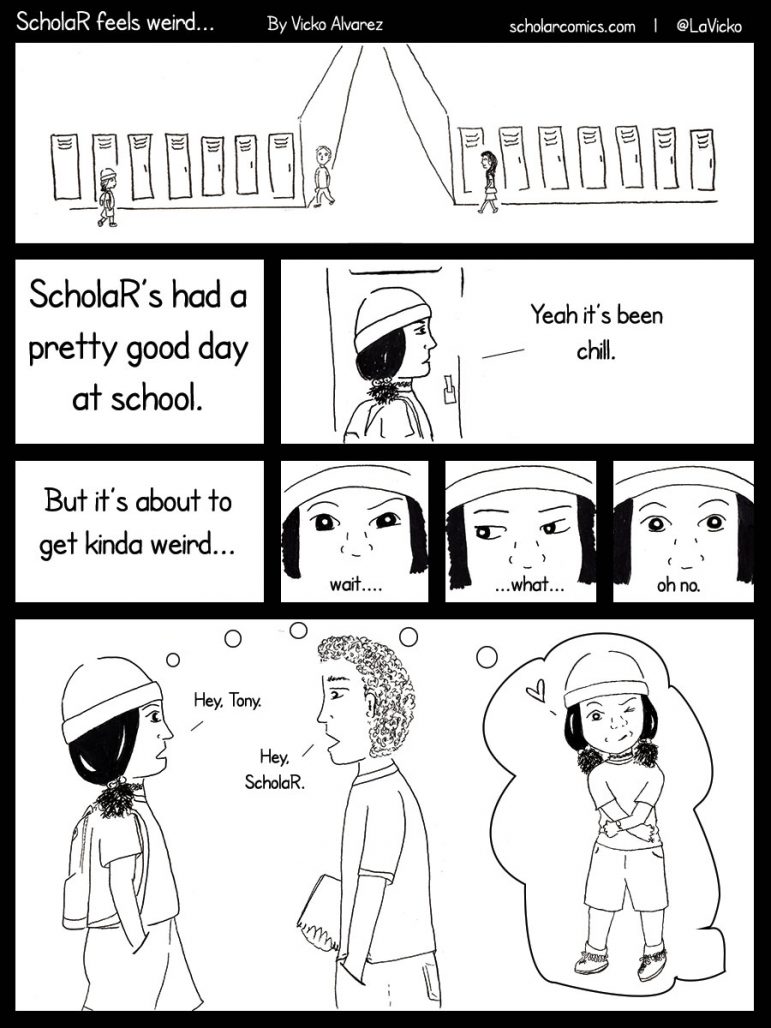

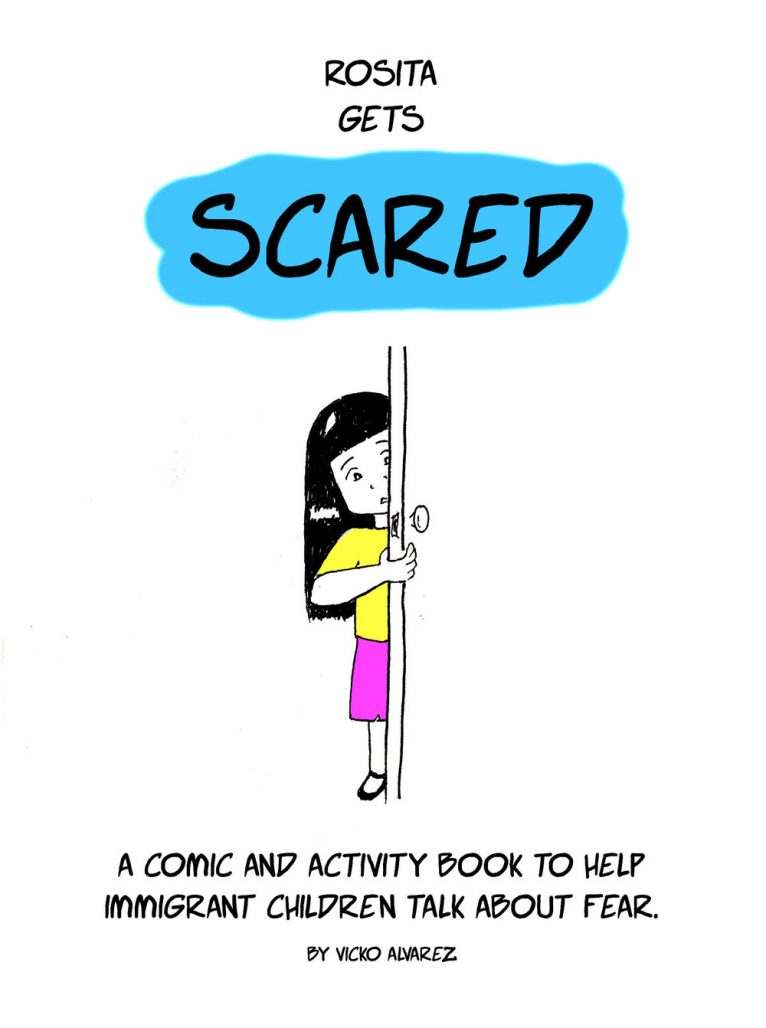

In this final CXC/Sol-Con interview, we talked with Vicko Alvarez. Vicko is a Chicago based comic artist, illustrator and teacher. Her work revolves around activism and education. Her comic series Scholar about a young girl going through life and high school. She graciously accepted to talk with me about Scholar and her latest comic Rosita Gets Scared.

—

Philippe Leblanc: For those readers who may not be familiar with you and your work, can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

VA: I’m the creator of a webcomic called Scholar. It started out as a monthly strip and eventually it became a long form project that’s also printed. Scholar is about a young adolescent girl whose name is Scholar as she’s going about her youth, figuring out the world without too much interaction from adults. She’s from a working class neighborhood and in these environments, you don’t always get guidance from adults in your life, so we see how she’s getting along without that input. Along the way.she starts to make friends, like Rosita for example. I even made a comic about that character called Rosita gets Scared that really took off. It’s about undocumented youth.

PL: Is Scholar your autobiography?

VA: It’s definitely close to autobiography, but not quite. I created the character as a representation of myself and as a way to sift through my own memory and emotions of having grown up in the same kind of environment and having to figure things out on my own despite having adults around me. They were usually busy, working class people, working from sunrise to sundown and barely having time to see your children or any youth that you might be taking care of. Survival comes first, money comes first and making sure bills are paid on time comes first. Scholar was a way of remembering how that was like, partially for myself, to be able to understand the opportunities that it led to and the experiences that I lacked emotionally and socially. I also wanted to better understand my students. Scholar started when I first became a teacher and I think that going back to my own adolescence helped remind me that I need to see things from the point of view of my student as best I can, so it helped me try to remember how this was as well.

PL: Are you including some of the experience of the students in Scholar? It seems like you want to integrate those stories into your work to get a better understanding of these experiences and lives.

VA: Some of the stories are a mix between what I experienced growing up and what some of my students talk about. I think one of the very first comics I made was about Scholar watching telenovela and wondering why they’re always the same. Questioning why women are oversexualized, why is it always the same story “rich guy – poor girl”. Another story was one where Scholar is working at aunt’s shop for the summer and that was more taken from a student of mine I knew had a summer job with her family and she must have been no older than twelve or thirteen. It was taking place in a neighbourhood in Chicago that is getting gentrified. That really took a look at the politics of Chicago, the Latino community who are seeing a change happening there even as they’re simply going to a shop.

PL: I’m interested in knowing more about your career as a teacher. How you became a teacher and how comics became part of your professional path.

VA: I’m still studying to be a licensed teacher, but I’ve been working in after school and summer programming. I’ve taught a lot of different things, art courses for nine to thirteen years old students, adult education in math and most recently for after school programming for high school students through the Chicago park district. I worked with an organization that does work with children outside the classroom or after school program at an actual school.

PL: You describe yourself as an hociconas, a big mouth. I’m wondering how that takes shape in your comics work.

VA: Oh yes, I put that in my bio. I think Scholar probably is the closest thing to me in this way. I think she’s a wiser character than I was at that age, but it comes out whenever she says something openly. There’s a comic where she confronts a bully and he’s bossing people around and she’s not going to put up with that sort of behaviour at school. I remember being like that, though I’m not super tall so there’s only so much I could have done with a bully. It comes out whenever she refutes a question or when she sees something that isn’t right, like the bully for example. There’s also a young white man who came into her grandmother’s flower shop asking for something of which he didn’t fully understand the cultural significance to Latinos.

She can also be kind when no one else is. That’s another way this reflects in the work. When she meets Rosita, she’s introduced to school during Valentine’s day. Scholar went out of her way to give her some cards she can give out to people so she can be welcomed by others faster.

She also takes initiative to address something that she knows should be addressed. I’m outspoken and this comes out in that character. She has a big mouth, but it’s for a good cause.

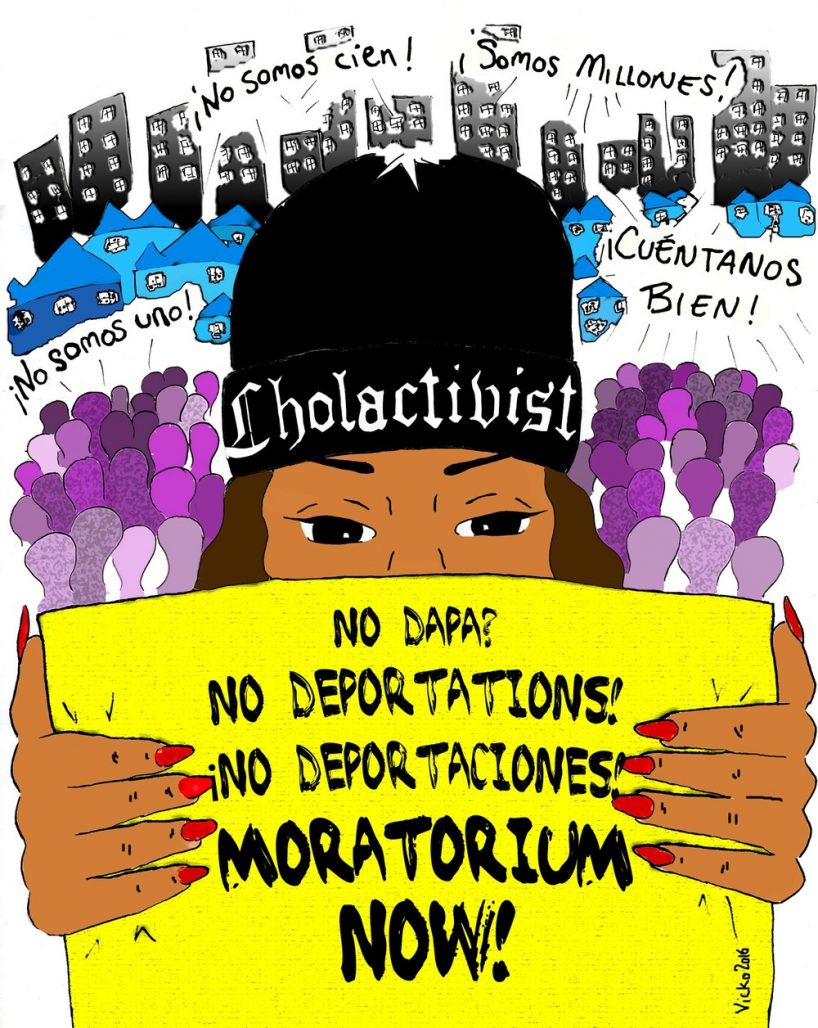

PL: Before we talk about your comics work and Scholar in particular, I wanted to talk about Cholactivist. Could you tell us more about what the movement is about and the work you’re doing for that?

VA: Cholactivist and Scholar both branch off of Chola culture. Cholas is a term that originated in the 80’s to identify young women who needed to identify for themselves who they were as descendants from another country, but really having only ever known the US and who they were as working class people and people stuck between two places. It’s often people whose family were displaced from their country and ended up in these working class or low-income neighbourhood with little family service access. They’re more at risk of experiencing violence and hardship. A lot of the Chola culture revolves around the creation of gangs and the creation of looks and appearance of who you want to be.

For a long time it was seen in a negative light, though it’s not entirely the case anymore. It was viewed as young girls who were too violent, who couldn’t speak English or Spanish properly and who were raised in the streets essentially. For them though, it’s not what this is about. For these women, it was more about survival and rebuilding a community and support when no one else was around to provide that. Scholar comes from this evolution of the Chola culture and the way people see it now. I thought, you can’t say scholar without chola. These women can be tough on the outside, but they’re multifaceted women. They enjoy art, life and other things. Cholactivist became a word I use to define what this identity could mean for me. It’s about community building and activism, women advocating for themselves. It’s its own form of activism, even though that’s not an official title. It connects to the social justice work I do that is unrelated to my comics work. I do illustrations for organizations that may need flyers or other type of art.

PL: Do you feel like you’re accomplishing what you set out to do with Scholar? Does it help you work through childhood experiences, or convey a message about childhood?

VA: I never had too much expectations for Scholar. It started out more therapeutic than anything. I had a stressing lifestyle and job at the time and I needed to return to art. The easiest way was with pen and paper and I did it for fun. It was a way to find a calm place for myself. When it took off, after I had posted it online and people were talking about it, I started feeling that putting my story out there resonated with people. I started seeing the potential to relate to people. That my stories had an impact on people’s lives.

When I became a teacher, I saw the potential for children as well. I wasn’t sure that kids were going to relate to it, but I started testing it out. It’s provides a medium to talk honestly about life events and issues that I’ve faced that others are facing as well. It’s refreshing to see somebody talk about it in a comic. It’s doing i’s job on a personal level. It’s therapeutic and not overwhelming. I take everything at a good pace so it doesn’t become like work. Now, seeing that it’s a relatable tool to connect with people, I’m really glad. I definitely want to do more with it. I don’t think monthly comics is enough. I started doing printing zines once my time was a freed up, new stories in zines, because I wanted to elaborate on my characters I want to continue doing these short stories, but I’d like to create a graphic novel in the future. I think I still some time to go to develop my stories and characters, but I really like where the zines are going and I’d like to do something longer.

PL: Your latest comic is called Rosita Gets Scared. It’s about a young undocumented girl coping with her fear of deportation as well as providing advice to young readers to cope with their fears. It serves as both an activity book and a learning tool to engage young readers. How did you manage to distill this kind of experience for your comic and what made you want to tackle this subject?

VA: It happened organically, but there’s a few things I can point to. When I was studying to become a teacher, I took a class on social and emotional learning. That class talked how we teach math, science or English but schools at a point stop teaching how to manage emotions, how to interact with others, and kids are left to figure these things out on their own. We all remember middle school can be difficult as we try to navigate the world on our own. This really opened me to the idea that I could use my comics as a tool for social and emotional learning. There wasn’t a lot of material for students of colour. I didn’t see material that was relevant to their experience, relevant to their emotions, so it seemed natural that I could use Scholar. I wanted a comic book that could engage with younger students to talk about particular emotions. The first one I created before Rosetta Gets Scared was Scholar Gets Angry. It was to talk about anger in young girls. It talks about gender in terms of emotions. Scholar doesn’t want to smile for other people and she’s very protective of herself. She gets teased for being tough, for having a belly as she deals with body image around that time. These interactions she’s having allows readers to know her more and to open up. She asks what kind of things make you angry for example. There’s a lot of questions for the reader to think about.

I wanted the second issue to address fear. After thinking about my character Rosita, I thought that talking about being undocumented would be better. It’s extremely relevant in this year, but there’s never been a period in any child’s life where immigration doesn’t become a national issue. I connected with an organization in Chicago with whom I’d been in contact in the past to create material for children in different languages. I thought it would be a perfect fit to use my comic to address being undocumented and the fear that it can cause when you’re young and still trying to figure out what that means. In the book, Rosita tells her story, how she’s afraid that she or her mother will be taken from their home. She senses that something is wrong and she can tell in her own way that they are here undocumented even though she hasn’t quite understood what that means. She’s aware that she’s not from this country is how she phrases it. Her scary story isn’t about monsters under her bed or a fear of height, it’s that she knows someone has been deported from the apartment building they live in. She saw people come in, they weren’t police and they arrested someone she knew. She doesn’t know what ICE is just yet, but they took her neighbour and that causes a deep fear in her that she might also get taken. She talks about how she copes with it. The very first way is by telling her story, having someone that can understand her and with which she can communicate her fear is helpful. She addresses the reader directly and thank them for listening to her story. She also talks about that made her feel physically, how she was tired and weary and didn’t want to eat or play anymore. Those are signs of adolescent depression. She asks the reader how they feel when they’re scared and anxious. Do you have a headache, or a stomach ache. The reader can go through and circle the way they feel when they’re anxious. She also talks about what allowed her to address these fears was to ask questions. Understanding a problem helps. She asked her mother if they were undocumented and what happened to their neighbour and have her mother answer truthfully. It’s how the book concludes really. Young people need a space to be able to speak. Sometime, adults might think it’s too much for children, but it can cause more fear and anxiety than it alleviates because they’re kept in the dark. Far from me to tell people what to say to their children, but fostering an environment where they feel safe to ask honest questions that adults are uncomfortable with, then it helps to remove confusion and fear. Education and discussion helps to dissipate fear and foster an environment that’s healthy and positive.

PL: What do you want readers to take with them once they’ve finished reading your comics?

VA: I would want them to think back to when they were young. It’s sometimes been a while since we were young, but it was a part of our development. There’s effect from it that will always be with us as we develop into adults. Remembering a time when you were young can help you identify with the people around you, especially with kids and teenagers who have their own lives and experiences and sense of agency and opinions. They have their own issues and they deserve the same respect that we give everybody else.

—

You can follow Vicko Alvarez’s work on her website, or follow her on Twitter or Facebook. You can also buy his work on her online store or support her on Patreon!