In what may or may not become a long-standing tradition, Alan Moore has answered questions at Christmas set by the members of a Facebook group called The Really Very Serious Alan Moore Scholars’ Group, who are, as the name might suggest, a bunch of people who are interested in his work. At least, Moore answered 25 questions for the group in December 2015, which were later published here on The Beat over four posts towards the end of 2016. Those four posts can be found here:

Alan Moore’s Secret Q&A Cult Exposed! Part I: You Won’t Believe What They Asked Him!!

Alan Moore’s Secret Q&A Cult Exposed! Part II: You’ll Gasp When You See What He Told Them!!!

Alan Moore’s Secret Q&A Cult Exposed! Part III: This Will Completely Change Your Life!!!!

Alan Moore’s Secret Q&A Cult Exposed! Part IV: At Last the Truth Can Be Told!!!!!

And I can only apologise for the faux-clickbait titles. At the time I thought they were hilarious. What a difference a year makes…

Anyway, Moore once again answered a number of questions for the group at the end of 2016 and, having allowed the group to savour these on their own, the time has once again come to share them with the wider public. They cover subjects from Food to Fiction, but we’re starting with various aspects of Magic and Art.

Rod McKie: Himself has said, along the way, that art is literally magic. That has the ring of truth, but there’s some really bad art/magic out there. Does that bad art/magic that is/has been produced over the years, come at a cost to us, collectively? And if so, can we do something about it, individually or collectively?

Alan Moore: There certainly is some bad art and thus some bad magic out there, and as an illustration of the sheer scope of its badness I think few figures serve as well as Charles Saatchi. In terms of his effect upon the world of the arts, he has used all of the magical techniques – the manipulation of symbols; the repetitive incantatory power of the slogan – that he learned in the world of advertising to transform the world of art into, effectively, an advertising landscape in which the only considerations are commercial and relate to perceived status/brand visibility. This, in my opinion, has massively disempowered and neutered the arts, robbing them of any power to make genuine statements that aren’t subsumed beneath layers of irony and defusing all of that vital cultural criticism and commentary, however veiled or oblique, that should always be at the centre of genuine art.

you look at the advertisement in question, realise there’s no product name attached to it but that the central element is golden in colour, which brings to mind the B&H brand-name and makes you think “Hm. That’s stylish and clever”, which is the end of your involvement with this piece of advertising art. I suggest that if these principles are applied to actual art the effect is ruinous, leaving us only with pieces of conceptual art which, once you’ve understood the demi-concept or once you’ve got the gag, then you need never look at that piece of art ever again as there will be nothing new to find in it.

Advertising itself is the most blatant form of bad magic being practiced in the world today. Its practice progresses in leaps and bounds, even without the personally-targeted advertising which the internet allows, while our human neurology and our capacity to deal with these techniques progresses at a much more leisurely crawl. I was taking recently with the highly respected magician Lionel Snell, who was pointing out that rational statements, if anything, tend to lose power with repetition, simply because we become used to them and they seem commonplace or boring. Magical incantations, however, many of them in languages that the practitioner does not even understand, will actually gain power from repetition. Clearly, under the rubric of magical incantation we should include the slogan, be it for commercial advertising or for political purposes.

The slogans ‘Brexit Means Brexit’ or ‘Let’s Make America Great Again’, while they mean precisely nothing, if repeated enough times with steadily increasing volume will come to seem like profound eternal truths.

And of course, the purpose of repeated incantation in magical practice is to raise or evoke some specific kind of energy. This can sometimes be more powerful or dangerous than had been previously anticipated, which is why occultism is full of all those bothersome and tedious banishing rituals: the banishing is to symbolically and psychologically dissipate and put to rest any symbolic or psychological forces that may have been awoken by the working. I’d submit that one doesn’t have to literally believe in demons for the above to make practical sense, and that one need only look at the recent successful uses of incantation in England and America to see that powerful and injurious forces have indeed been unleashed without any awareness of what such forces can do, or what happens if you don’t conclude the working by banishing them successfully.

As to the best way that we can do something about this, I can only say that I would advise against fighting fire with fire, an adage that cannot conceivably have been coined by anyone who had ever even seen the phenomenon of fire. If physical violence is met with physical violence, then all we ever end up with historically is twice the amount of physical violence. Similarly, faced with the kind of manipulative promotional magic that has played such a part in our recent transatlantic political catastrophes, we should not resort to the same propagandist means and strategies, as all we would end up with would be twice the amount of lies, distortions and manipulations. We’d end up with a reality even more vaporous and fragmented than the one we have at present.

As far as I can see, it is the duty of any self-respecting magician or artist to counter this bad juju with a better juju; this bad art with a better art. It is the responsibility of any creative individual to speak as clearly and as truly as they can, at the top of their voices and the full extent of their talents. It is our job to banish the damaging ideas that have been called into being by picking them to bits and denouncing them with passion, with ridicule, with intelligence, with art, with science, or whatever other magical weapons we happen to possess. In my personal opinion we are in for a very bumpy few years, although I’m expecting the consolidation of opposition to the prevailing anti-humanitarianism to be a major and significant consolation. We are having a wretched, idiotic and potentially suicidal narrative imposed upon us, and it’s up to all of us to come up with a better, and better-integrated one.

Flavio Pessanha: Your works were already laden with mysticism before you turned 40. What changed since you became a Magician?

After my 40th birthday I think you’ll find that my approach to the occult in my work is changed. As an example, I couldn’t have conceived of any of the spoken word pieces such as The Birth Caul without at least a strong belief in magical working processes, and I certainly couldn’t have produced Promethea in the way that I did. By this I’m not just referring to things like the tour of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life (although that is certainly an example) but more to some of the more technically accomplished issues, like issue 12 or issue 32. In both these cases I only persevered with my impractical-looking original plans for these issues – even though at that point I believed the task I’d set myself was impossible – because I believed the inspiration for these works to have had a divine origin, and working on the logic that gods probably couldn’t make mistakes I assumed my own reasoning to be faulty and thus persevered until the books emerged in exactly the way that I’d imagined them.

This may not sound like a feat of magic to people raised on fantasies of magic, but the fact remains that without a belief in gods and magical processes, whether gods and magical processes can actually be said to exist or not, two of the most accomplished works of my comic book career would never have come into being. As for what is probably an equally underwhelming example from my day-to-day life, I’d say that my understanding of the alchemical formula

Alan Moore: I know that I’m generally described as a ‘Ritual Magician’, and while I have of course enacted rituals in the past I have the feeling that the word ‘Ritual’ is usually included because it sounds more important than just plain ‘magician’ and also perhaps to denote a difference between what I do and what stage magicians do. The truth is that in my own experience I’ve found that as I’ve progressed as a magician there has been less need to externalise the processes in the form of ritual. For one thing, I’ve long since foresworn magic that seeks to enact some relatively minor practical change upon the world, and even my last pieces of ritual working were purely about effecting specific changes in my own consciousness. Although I wouldn’t rule out a return to ritual should the need or the inclination arise at some point in the future, for quite a long time now my magical workings have been conducted entirely within my head which, as a process, seems to be working satisfactorily. Of course, until a couple of years ago they were conducted within Steve Moore’s head as well, which was a considerable benefit, and the loss of Steve is something to which my magical practice is still adjusting.

That said, though, I’m happy with the results thus far: no, there was no specific ritual worked in the course of writing or conceiving Jerusalem. Instead the whole project was the ritual, meaning that rather than performing a ritual to produce a successful book, the book itself is the ten-year ritual working that is intended to have a certain (hopefully beneficial) effect upon the consciousness of its readership. According to the definition of magic that Steve and I arrived at, namely “any purposeful engagement with the phenomena and possibilities of consciousness”, Jerusalem seems to me to be my most sophisticated and complex magical working thus far, and certainly the most ambitious in its aims. I suppose that with regard to formal ritual, I was coming to see it as a way of compartmentalising magic; almost quarantining the magical part of your life off from the rest of it. Although there are often very good reasons for doing just that, in my own life and circumstances I didn’t see any reason why I shouldn’t allow the magical worldview to become my default perception of reality.

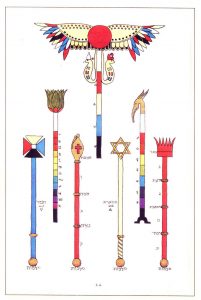

To me, at least at the moment, everything is magic, and to underline some part of that great complexity with ritual – to suggest that it is more meaningful or more magical than the rest – seems to me to be redundant. There may also be an element in this that relates to having practiced magic for more than twenty years now, in that in my first few years as a magician I perhaps needed the spectacular results that can come with ritual magic just to demonstrate to myself that there was something real at the heart of this new experience. Now, however, I don’t doubt for a second that magic has something real at its heart, and in fact currently view magic as reality itself. And I suppose that if your workspace is surrounded by as many Golden Dawn magic wands and carefully-painted Enochian watchtowers as mine is, then even making a cup of tea becomes a ritual in more than the ordinary sense. And if you happen to believe that it’s an eternal cup of tea, then so much the better.

Rod McKie is a British cartoonist and illustrator. He has worked for The Wall Street Journal, Harvard Business Review, Reader’s Digest, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, National Lampoon, and many other publications.

Flavio Pessanha is the administrator of the Alan Moore BR Facebook page.

Phil Sandifer is the author of the brilliant Last War in Albion.

Alan, magic is dangerous, be careful

Comments are closed.