It was only a matter of time. You know that, right?

“It’s a joke. S’all a joke.”

Watchmen by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins is one of the most popular, influential, perennial selling comics in existence. Decades after its release, it remains so. In fact, earlier this month it was one of the headliners for DC’s new “Compact Comics” line. It’s beloved by creators and readers alike. And often recommended as something to give new readers, particularly adults, to show them what comics can do.

It’s easy to see why. I absolutely do think it’s a classic that everyone should read. But it’s not one that I would recommend as someone’s first comic. I mean, I get it — it is a self-contained mystery. A noir-tinged thriller with pulp sensibilities. A commentary on how superheroes might alter real world events like Vietnam and the Cold War. It features three creators at the absolute top of their game. A masterpiece of word and image that follows a structure and flow that you’d think is easy to follow. And it arguably fits into the “comics aren’t just for kids” category.

But it’s also kind of an inside baseball in-joke and features some of the densest storytelling possible. Mind you, both are positives and negatives depending on how you look at them. Granted, I think many take the wrong ideas away from the work.

“Who makes the world?”

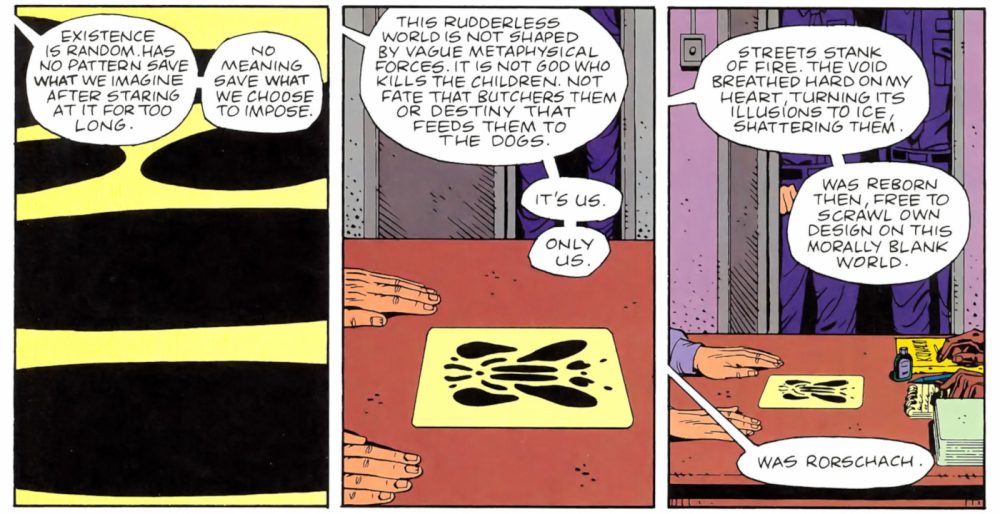

Life’s what you make it. Not just a catchy ’80s hit. It’s also kind of a rephrasing of one of the core ideas behind existentialism. Nothing matters except what you choose to make matter. I feel like that’s one of the underlying themes behind Watchmen. Also in a meta sense, because what you take away from the comic can be very different for different people. Some would say that’s one of its strengths.

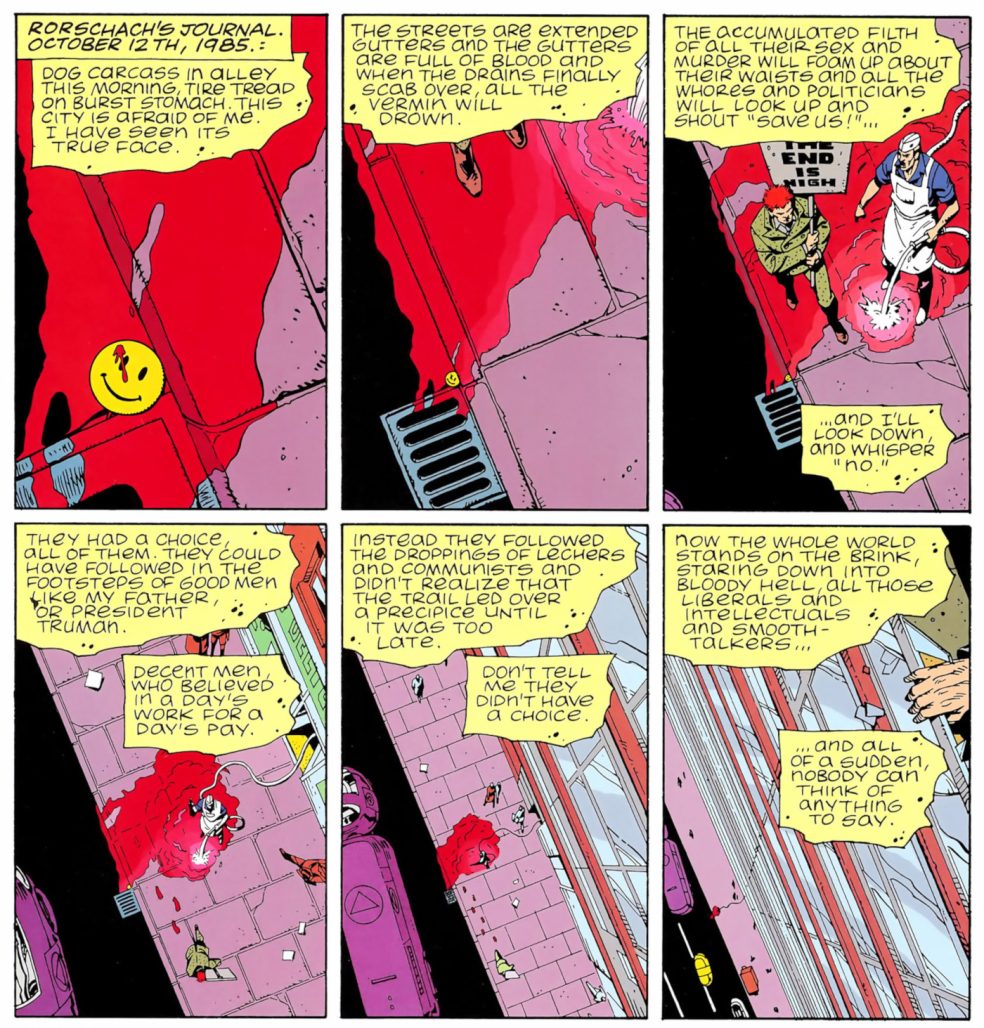

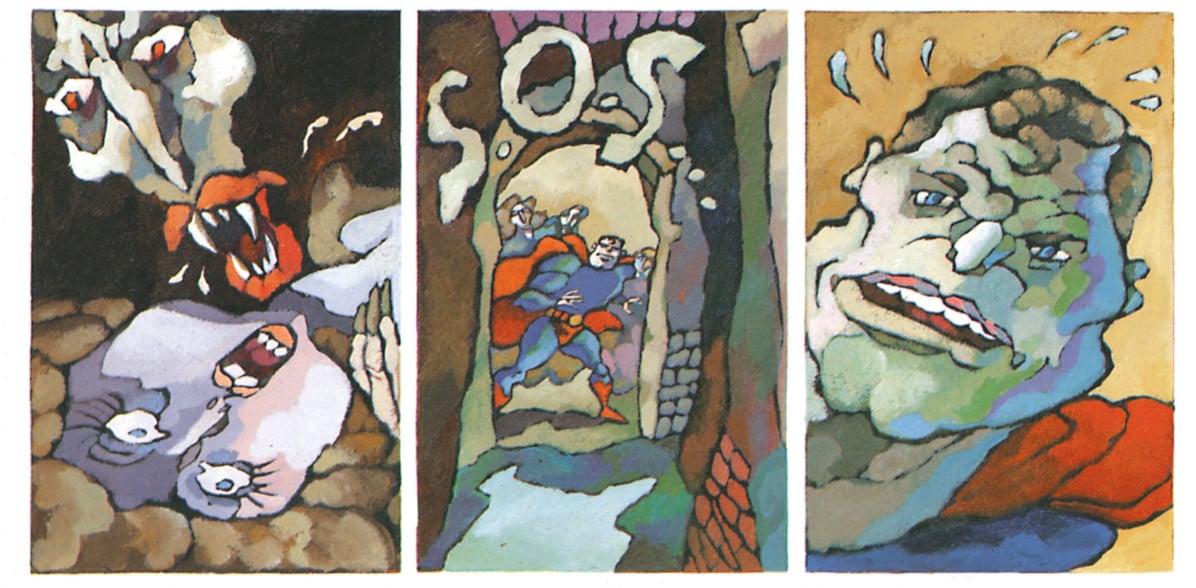

On a surface level, the story is a take on applying real world situations to superheroes. What would actually happen if these larger-than-life characters had to deal with real world situations. Many took that to mean superheroes should be grim and gritty. For me, it was a joke. Just not as obvious as other lampoons of the genre like Brat Pack and The Boys. That real world superheroes are patently ridiculous.

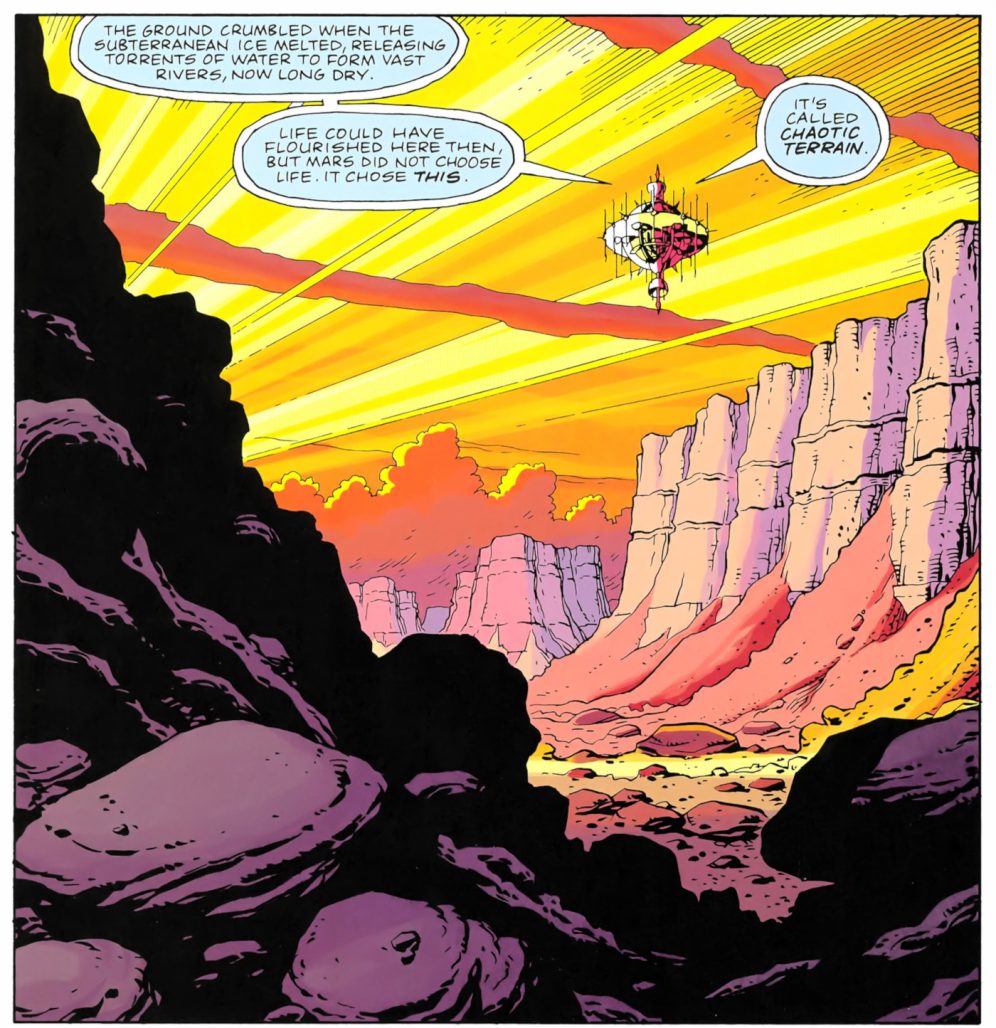

Each of the characters go to extremes of their beliefs, pushed into absurdity. It’s shown through the darkly funny violence and unhinged ethos of Rorschach. The clinical, fatalistic distance of Dr. Manhattan. Amoral apathy broken by calculated evil when The Comedian has to confront two irreconcilable modes. And more. But I think one of the most obvious signs that these are broken people, tainted by their lives rather than enriched because they’re patently absurd, are the two relatively normal folks, Night Owl and Silk Spectre. That’s where it becomes cape fetishization.

This isn’t a glorification of superheroes. It’s a joke about why they should stick to brightly coloured adventures. But it’s like the Rorschach Test itself. You can see multiple things in the image.

“The Comedian is dead.”

And I think to see it my way, you need to be familiar with the Charlton heroes. You need to be familiar with numerous storytelling tropes within comics. Of origin stories. That you should come at this from a position of experience, rather than innocence. I see that mirrored in the structure of the comic.

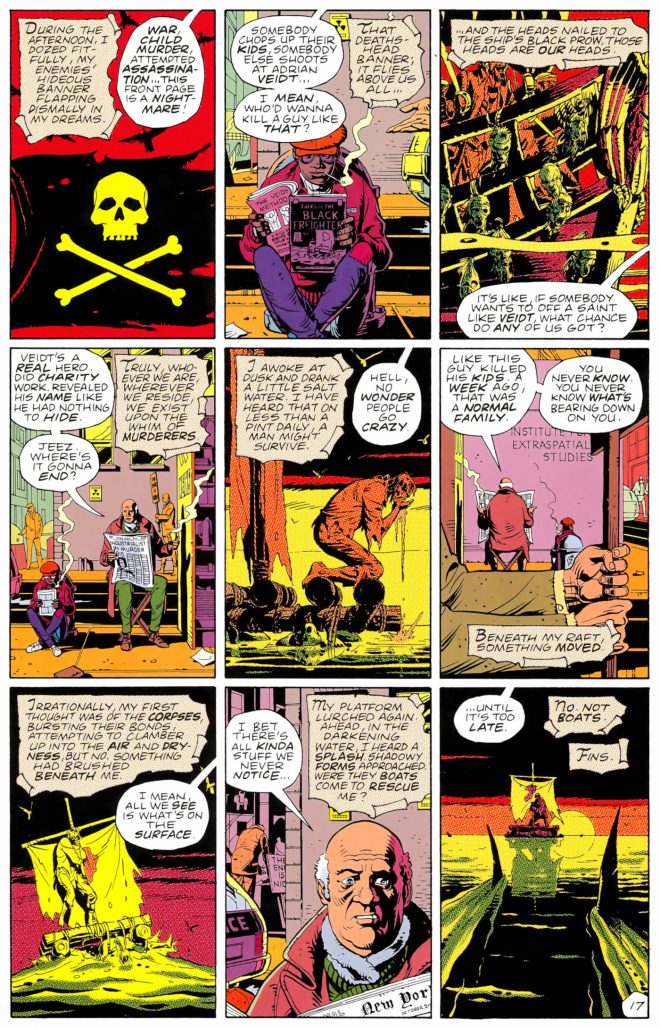

The 9-panel grid is probably one of the easiest to follow for a reader and maintain high complexity. There are other configurations that are probably easier to read, and dropping a grid allows for more visual diversity, but in terms of flow, rhythm, and structure what Dave Gibbons does here is incredible. It sets a beat, and plays within it depending on the individual sequences. Paired with John Higgins’ stylized colours, it’s visually stunning.

It’s incredible work, though I think when it’s coupled with multiple overlapping narratives on the same page, it can present something that I think you kind of need to already know the syntax of comics to really follow. Even then, I’ve seen many people admit that they’ve just skipped over the entire Tales of the Black Freighter sub-story. Like the side stories of the incidental characters in New York, it can become an Altman-esque cacophony. Another kind of test to see what you make out of it.

“I leave it entirely in your hands.”

I’ve barely scratched the surface of Watchmen from Moore, Gibbons, and Higgins. It’s undoubtedly one of the reasons why so many of us come back to it. Re-read it. Analyze it. Try to figure out how it ticks. How the clockworks were made. And why we recommend it to other people to read. That maybe we’re trapped in our own misting of Nostalgia.

And that some will see a pretty butterfly. Others something far more troubling.

Classic Comic Compendium: WATCHMEN

Watchmen

Writer: Alan Moore

Artist & Letterer: Dave Gibbons

Colourist: John Higgins

Publisher: DC Comics

Release Date: May 13 1986 – July 28 1987 (original issues)

Available: Watchmen – Deluxe Edition

Read past entries in the Classic Comic Compendium!

“What if superheroes were real” is a pretty stupid question to begin with. The answer is that they would die pretty quickly. Nobody seriously asks that question, not even Watchmen. This is what if superheroes had explicit sexual psychoses rather than implicit. For all of its formalist novelistic structure its pretty blatant. Nite Owl actually says impotent just in case you didn’t get it.

Comments are closed.