The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

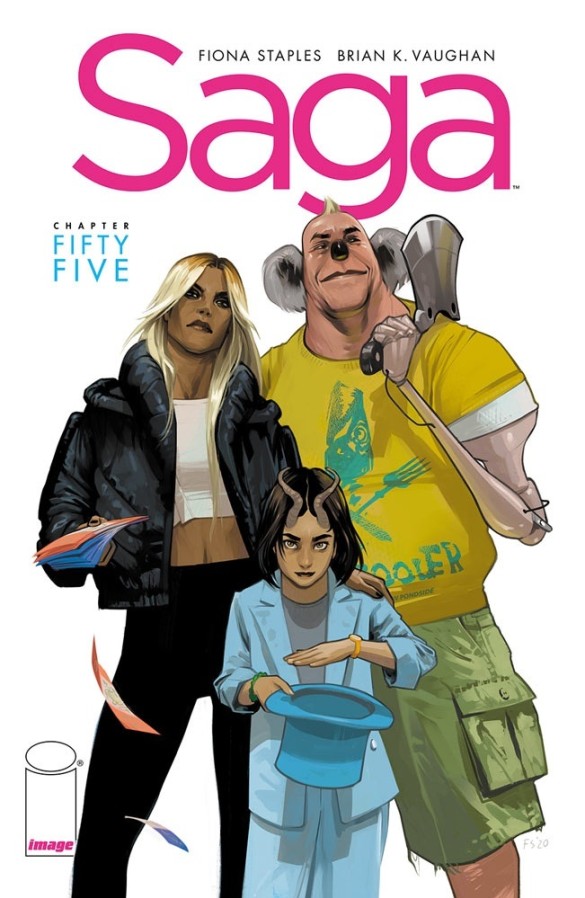

On January 26th – less than two weeks after the publication of this essay – Saga finally returns to shelves with its 55th issue. Almost four years have passed since the last chapter, and since writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Fiona Staples announced an “indefinite hiatus.” Ever since I helped break the news about the sci-fi/fantasy epic’s return at New York Comic Con 2021, Saga #55 has easily been my most anticipated comic of 2022.

It’s not just that Saga is a brilliantly-crafted comic, although of course it is. We’ll get to that later. It’s that Saga holds a special place in my heart for being the first independent comic I followed on a month-to-month basis. I’ve written about this before, but my way into comics fandom was a bit of an unusual one. I was a late bloomer, for one thing, and as much as I liked to read the newspaper funnies as a young child, it wasn’t until I read Maus at the rough age of 13 that I truly discovered the medium’s artistic and literary potential. I’ve told the story of how I started following monthly superhero adventures, too. But falling in love with Saga was a different story. Perhaps it represented me leveling up in my newfound identity as a comics enthusiast.

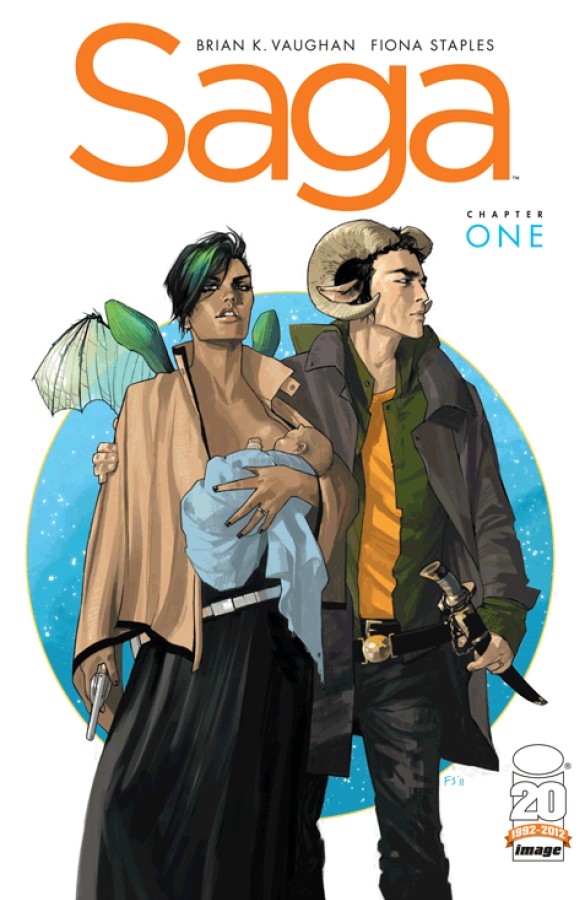

By the time Saga #1 was released in 2012, I was well on my way to becoming a budding comic book expert. I knew more about comics than anyone else in my life at that time by far (this would quickly change by the next year, when I joined the comics criticism community). In the early 2010s, it was already quite easy to learn about all the “essential” comics to read if you were even halfway internet savvy, and while the comics internet certainly led me astray more than a few times (sorry, but I couldn’t even finish Batman: Hush), it was simple enough to google a bunch of “best of” listicles and devour whatever I could find at the library or on the discount shelf of my LCS.

In other words, while I read a great many bona fide masterpieces up to that point, they were still, in a sense, “safe” choices. Either they were years-old graphic novels with well-established reputations, or they were new, but familiar, superhero comics like the latest issues of The Flash or Wolverine & the X-Men.

But I was also getting in the habit of following comics news sites like IGN (which used to have much more robust comics coverage) and Comics Alliance (now-defunct). Everyone seemed to be talking about this new comic called Saga. Apparently the writer was some big shot who hadn’t written a comic in a few years, but I hadn’t heard of Brian K. Vaughan, nor the artist, Fiona Staples. It looked like it might be kinda neat, but I didn’t pick it up during the initial 6-issue arc’s publication. “Star Wars meets Romeo and Juliet” was the pitch I kept hearing, and that didn’t sound especially interesting. I still hear Saga described as such to this day, and I hate how reductive it is.

Still, by the time the first Saga volume was released as a trade paperback, the measly $10 price tag convinced me to see if the hype was real. Almost from that first, iconic page, I knew that I was in for something special. Perhaps it’s because right away, I saw that Vaughan and Staples are masters of harnessing shock value. Yes, it’s shocking to open the debut issue of a slickly-printed comic book and immediately get with a close-up of a woman in labor (Alana) furiously asking her husband (Marko) “am I shitting? It feels like I’m shitting!”

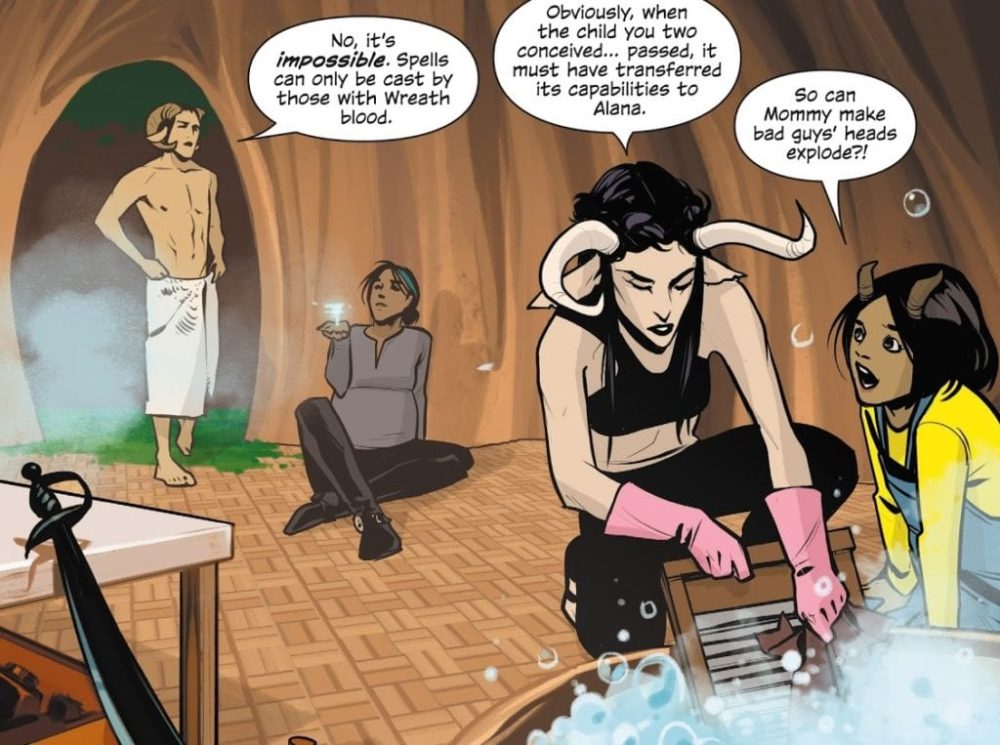

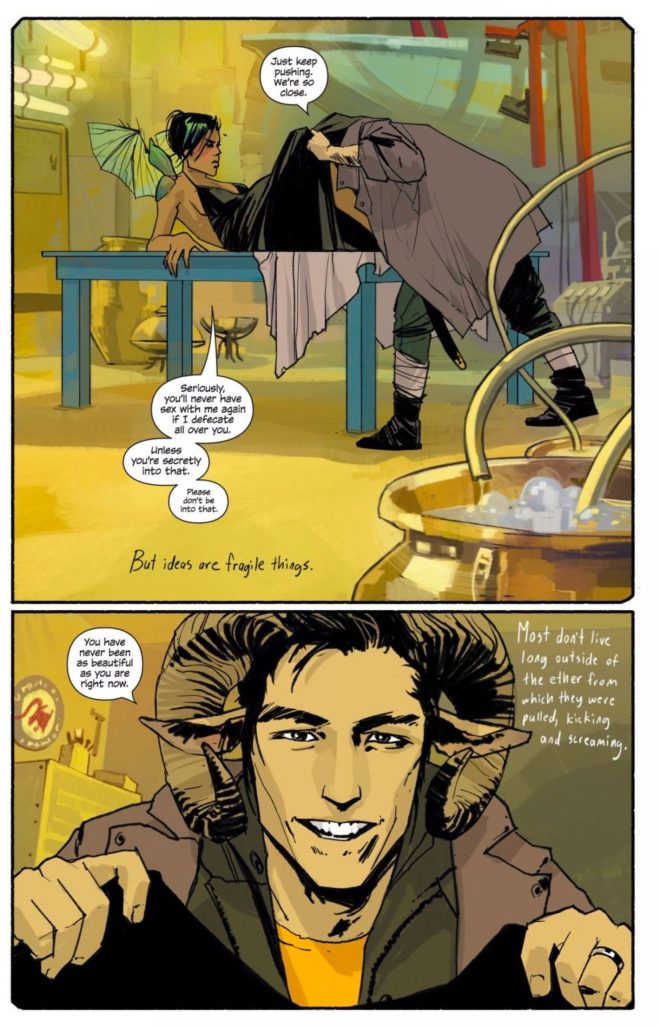

It effectively grabs the reader’s attention from jump, but it quickly becomes evident that there’s more at play here than mere provocation. We’re told that as fantastical as the overarching story may be, the execution will be characterized by raw, realistic emotions. From interspecies childbearing, to intergalactic war, to robot-on-robot fucking, nothing in Saga is sanitized or compromised. Despite the fantastical outer space setting peppered with quirky creatures, Saga is a book about how sex, violence, and all the consequences thereof are messy. 54 issues and a full decade later, that “am I shitting” opening still reads like a mission statement.

I also want to acknowledge Fonografiks‘ lettering, which probably doesn’t get as much credit for its contributions to Saga‘s aesthetic as it should. Using sentence-case rather than comics’ traditional all-caps for the dialogue pairs nicely with Staples’s hand-lettering of Hazel’s narration, and the combo constantly reminds readers that we’re reading a first-hand account of what happened to Alana and Marko’s daughter as a child. There’s a conversational quality to the lettering.

I’ll admit that I’ve familiarized myself less with Staples and Fonografiks’ work than I have with Vaughan’s, but one thing I’ve noticed about BKV’s comics is that, as with Saga, he delights in surprising readers. Few writers consistently do opening splashes or last page reveals better than Vaughan. I was about to write “it’s never shock just for shock’s sake,” but honestly, that doesn’t feel entirely true. You wouldn’t write a giant monster with a massive, exposed dong into your comic if you weren’t trying to grab the reader’s attention. But I guess what I mean is that the shock never feels cheap. Could the same story be told without as much nudity, profanity, or ultraviolence? Perhaps the same essential beats would be there, but it would be less funny, less memorable, and less thematically meaningful.

Shock is indeed a running theme in Saga, because regardless of the genre trappings it’s an epic story about things most of us can relate to like volatile relationships, dysfunctional families, shame, hope, loss, and so much more. Our ordinary lives have more shocking moments than we probably give ourselves credit for, and Saga’s amplification of this motif may help us come to realize that.

I fear I may be focusing too much on the raunchier bits of Saga, because what really makes the series special is its aching beauty. It’s aesthetically beautiful to be sure, but its story of desperate people (or at least people-like creatures) across the galaxy desperately trying to survive and support the ones they love is deeply moving. It’s there in the overarching mega-plot, and also in smaller, more intimate moments.

Take Lying Cat, for example, probably the closest thing Saga has to an iconic mascot. She’s a large, severe-looking cat who can tell when people are lying, and only ever utters one word: “lying.” That helps her owner, bounty hunter The Will, on his seedy adventures, and it also became something of a meme among Saga fans. But in one brief, memorable moment, she became so much more than that. Sophie, a former child sex slave rescued by The Will, laments that the abuse she suffered rendered her “all dirty on the inside…” before Lying Cat simply replies “lying.”

I also find beauty in the Saga fandom. After reading the trade paperback of the first six issues, I started picking up Saga in single issues from #7 onwards. Immediately, I fell in love with the letters pages. I always love reading the letters pages, and it’s disappointing that those have been dying ever since I started reading comics. They can be a time capsule of the time in which the books were published, and they also allow you to see another side of the people involved. Brian K. Vaughan in particular, who maintains a limited online presence, seems to cherish his opportunity to connect with readers. He’s candid, funny, honest, and willing to engage with criticism gracefully and without judgement.

For instance, I think a lot about BKV’s response to a letter from a boy who I believe was about 12. Vaughan often receives letters from children and usually makes humorous comments about how they’re too young to be reading Saga, but never admonishes them for it. Anyway, this boy asked Vaughan for writing advice, and Vaughan advised that one of the best things he could do – not just for writing, but for life – was befriend girls. It makes you better at writing women, and also makes you a more empathetic person in general, which is key to becoming a good writer. As a cis male writer who’s had friendships with women since preschool, that spoke to me.

Those intimate moments with fans shine a light on the soulfulness that characterizes Saga. It shines through among the fandom; that NYCC 2021 panel was one of the warmest con experiences I can remember, with fans of all stripes bonding over this wild, filthy comic. Vaughan reiterated there something that he’s mentioned numerous times throughout those letter columns: that while Hollywood has taken interest in adapting Saga into a feature film or television show, none of the offers have ever felt right. He and Staples see Saga as a comic and only a comic. For all the runaway success of Saga, it’s nice to know that a great comic need not be anything but just that.