Tribally-owned Great Oak Press was established a decade ago by California’s Pechanga Tribe and has provided an avenue to nurture and expand the knowledge of indigenous voices. The publishing house was at San Diego Comic-Con on July 26, 2024 to promote two titles in their repertoire and to talk about language revitalization projects through Chag Lowery’s graphic novel, Soldiers Unknown.

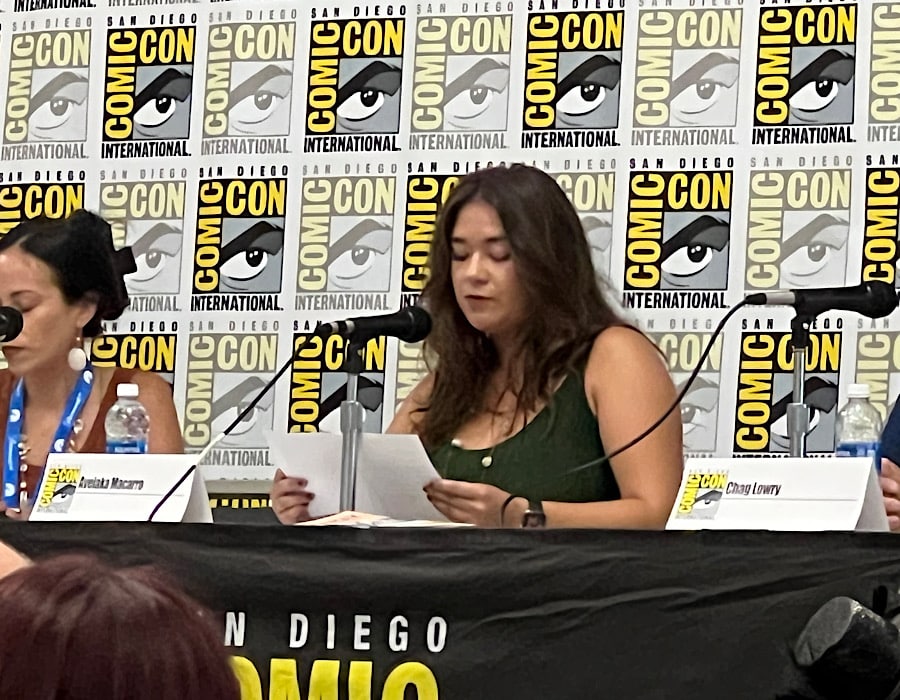

Great Oak Press director and editor-in-chief Lauren Niezgodzki and Kumeyaay artist Johnny Bear Contreras moderated “Writing Their Realities: California’s First Indigenous Press,” which included Lowery and writers and editors Camaray Davolos and Avelaka Macarro of the Pechanga Tribe.

Macarro kicked off the discussion with a reading of “Regeneration” by Marlene Dusek of Pay-mkawichum, Kumeyaay-Ipai, and Cupa descent before launching into the mission of Great Oak Press.

“One of the things that’s quite different is our editorial board is made up of people from our cultural resources department helping sensitivity readers, fact checkers, language speakers, professionals in Indigenous Studies,” explained Niezgodzki.

“Our executive board is made up of our tribal council, so we look to them for guidance and approval and moving forward with our projects. One of the things that’s really unique about our press is that we were not recruited to be profitable. We were created because we have a mission in mind, and that was to create a platform for indigenous authors and artists. Our main goal is to be advocates for indigenous voices and publish works that are important to indigenous peoples.”

As a Native American studies major at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, much of the course readings focused on Northern California indigenous cultures. Sensing an opportunity to fill in the gaps for Southern California sources, Davolos returned home and to Great Oak Press with the mission of uplifting the history of indigenous women in Southern California.

“Some of our native people, I’ve heard say, that Southern California native folks don’t have culture anymore, which is really hurtful and false. And if they’re thinking that and saying that, then what are non-native people thinking and saying about us? So, that was kind of how Yáamay came to be, this understanding that we need more perspectives and primary source material that deals with our voices, telling our joys, our triumphs, our real histories, and everything in between.”

According to Macarro, Yáamay took five years from initial concept to production, with Macarro, her cousin Rebecca Macarro and Davalos working remotely to collect stories through text messaging, Facebook and Instagram. This work allowed the trio to reconnect with their tribal roots, and Great Oak Press allowed them to retain control over the narrative being produced.

“Right now, there is a wonderful push for native representation. Marvel has two native characters. There’s a push online to make Wolverine native because he is from Canada. And because he is from Canada, there’s potential to be a First Nations person. That’s the deal for me, but thinking of this media representation, it’s still in the confines of that big budget,” said Macarro. “This matters to us because it makes a huge difference in what we’re able to produce, as well as the care for people that are purchasing from us.”

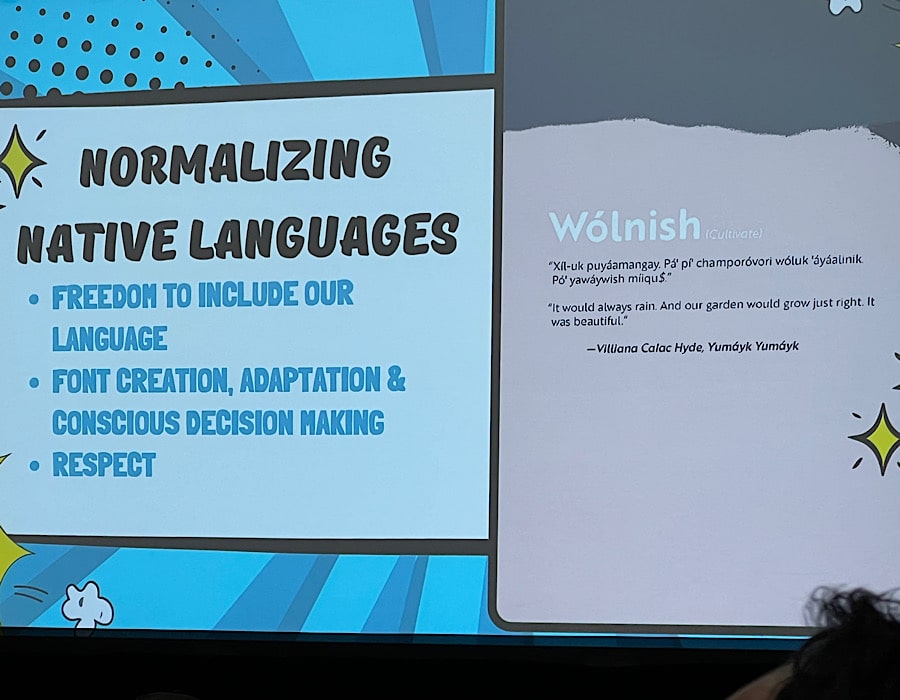

Davolos spoke of how Niezgodzki encouraged the trio to use Wólnish, their native language, all out of respect for people’s culture and people’s perspectives. Part of the process involved hiring linguists and font creators and tribal printers to include special characters that would more accurately reflect the intricacies of the language. That, according to Davolos, is what distinguishes Great Oak Press from other publishers.

“It was really important for us to find ways to live language and the way the family respects it. It’s also part of the organization, part of the idea of telling our own stories, utilization our own language pays respect to our ancestors who are able to maintain and cultivate it,” said Davolos. “Cultivate, not just this idea of protecting it, but letting it grow in a different style, in different ways, and developing something.”

Documenting the language, according to Davolos, is important in preserving a cultural legacy that Western civilization have devastated, a way to reclaim their collective voices. Lowery went a step further by highlighting how the language reflects upon larger environmental concerns and the impact that governmental policies have had in defining land relationships.

Lowery’s graphic novel looks at native people, and his family’s generational relationship of service, in the military from World War I onwards.

“Native people were not US citizens at that point, which always blew my mind” he explained. “So, I had worked with the artist [Rahsan Ekedel] for a little over three years to create this book, and at the tail end I happened to meet Lauren. I really appreciated her relationship at the press because I don’t care for publishers. I produce my own work, and the people are my editors.

As a native people, we deserve to own every aspect of the structure that produces our stories, and for a such a long time, we have not been able to own that structure. So, this very historic.”

With Soldiers Unknown, Lowery and Niezgodzki made a concentrated effort not to “otherize” the language. They wanted to preserve the language and allow readers to experience storytelling from the combination of pictures and text. This is a concept that Great Oak Press carries into its many projects.

“We have a lot of children’s books that we’ve developed, and like Chag was saying, these are not vanity projects. We create these books with intention,” said Niezgodzki. “These books are used in our children English School, which is on the reservation. Teachers have to know the language to be able to teach us. But we’re not stopping there. We have been in discussions with the school districts. We’re trying to change the curriculum. That is our ultimate goal. We want to correct the narrative that we’ve pulled time and time again.”

Stay tuned for more SDCC ’24 coverage from The Beat.